A Phase II Study of the Safety of Olanzapine for Oxaliplatin Based

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolution of Refractory Pruritus with Aprepitant in a Patient With

Case Report Resolution of refractory pruritus with aprepitant in a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma Johanna S Song, MD,ab Hannah Song, BA,a Nicole G Chau, MD,ac Jeffrey F Krane, MD, PhD,ad Nicole R LeBoeuf, MD, MPHabe aHarvard Medical School; bDepartment of Dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; cCenter for Head and Neck Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; dHead and Neck Pathology Service, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and eCenter for Cutaneous Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, all in Boston, Massachusetts ubstance P is an important neurotransmit- biopsied, and the patient was diagnosed with MAC ter implicated in itch pathways.1 After bind- with gross nodal involvement. Laboratory findings ing to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), including serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, substance P induces release of factors including complete blood cell count, thyroid, and liver func- S 2 histamine, which may cause pruritus. Recent lit- tion were normal. Positron emission tomography- erature has reported successful use of aprepitant, an computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was NK-1 antagonist that has been approved by the US negative for distant metastases. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment Treatment was initiated with oral aprepitant – of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, for 125 mg on day 1, 80 mg on day 2, and 80 mg on treatment of pruritus. We report here the case of a day 3 –with concomitant weekly carboplatin (AUC patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) 1.5) and paclitaxel (30 mg/m2) as well as radiation. who presented with refractory pruritus and who had Within hours after the first dose of aprepitant, the rapid and complete resolution of itch after adminis- patient reported a notable cessation in his pruri- tration of aprepitant. -

HHS Template for Reports, with Instructions

Texas Vendor Drug Program 1.1 Drug Use Criteria: Substance P/Neurokinin1 Receptor Antagonists Publication History 1. Developed December 2003. 2. Revised September 2020; September 2018; September 2016; May 2015; August 2013; June 2013; September 2011; October 2009; February 2006; January 2006. Notes: Information on indications for use or diagnosis is assumed to be unavailable. All criteria may be applied retrospectively; prospective application is indicated with an asterisk [*]. The information contained is for the convenience of the public. The Texas Health and Human Services Commission is not responsible for any errors in transmission or any errors or omissions in the document. Medications listed in the tables and non-FDA approved indications included in these retrospective criteria are not indicative of Vendor Drug Program formulary coverage. Prepared by: • Drug Information Service, UT Health San Antonio. • The College of Pharmacy, The University of Texas at Austin. 1 1 Dosage [*] Current therapies for chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting (CINV) and post- operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) target corticosteroid, dopamine, and serotonin (5-HT3) receptors. In the central nervous system, tachykinins and neurokinins play a role in some autonomic reflexes and behaviors. Aprepitant is a selective human substance P/neurokinin 1 (NK1) antagonist with a high affinity for NK1 receptors and little, if any, attraction for corticosteroid, dopamine, or 5-HT3 receptors. Rolapitant (Varubi®), the newest substance P/NK1 antagonist, is FDA- approved to prevent delayed CINV with initial and repeat chemotherapy courses including, but not limited to, highly emetogenic chemotherapy in adults. Combination therapy including netupitant, a substance P/NK1 antagonist and palonosetron, a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (Akynzeo®), is now available to prevent acute and delayed CINV with initial and repeat chemotherapy courses including, but not limited to, highly emetogenic chemotherapy in adults. -

Gastroparesis: 2014

GASTROINTESTINAL MOTILITY AND FUNCTIONAL BOWEL DISORDERS, SERIES #1 Richard W. McCallum, MD, FACP, FRACP (Aust), FACG Status of Pharmacologic Management of Gastroparesis: 2014 Richard W. McCallum Joseph Sunny, Jr. Gastroparesis is characterized by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction of the gastric outlet or small intestine. The main etiologies are diabetes, idiopathic and post- gastric and esophageal surgical settings. The management of gastroparesis is challenging due to a limited number of medications and patients often have symptoms, which are refractory to available medications. This article reviews current treatment options for gastroparesis including adverse events and limitations as well as future directions in pharmacologic research. INTRODUCTION astroparesis is a syndrome characterized by documented gastroparesis are increasing.2 Physicians delayed emptying of gastric contents without have both medical and surgical approaches for these Gmechanical obstruction of the stomach, pylorus or patients (See Figure 1). Medical therapy includes both small bowel. Patients can present with nausea, vomiting, prokinetics and antiemetics (See Table 1 and Table 2). postprandial fullness, early satiety, pressure, fullness The gastroparesis population will grow as diabetes and abdominal distension. In addition, abdominal pain increases and new therapies will be required. What located in the epigastrium, and distinguished from the do we know about the size of the gastroparetic term discomfort, is increasingly being recognized population? According to a study from the Mayo Clinic as an important symptom. The main etiologies of group surveying Olmsted County in Minnesota, the gastroparesis are diabetes, idiopathic, and post gastric risk of gastroparesis in Type 1 diabetes mellitus was and esophageal surgeries.1 Hospitalizations from significantly greater than for Type 2. -

Initial Public Comment for Aprepitant for Chemotherapy-Induced Emesis CAG-00248N July 6 – August 6, 2004

Initial Public Comment for Aprepitant for Chemotherapy-Induced Emesis CAG-00248N July 6 – August 6, 2004 Commenter: Duncan, Sariah, RN, BSN, OCN Organization: Date: August 2, 2004 Comment: Please Do Not Limit Anti-Emetic Coverage!! I don't think Emend should be considered full replacement for other covered treatments for chemotherapy induced emesis. On the few patients who it was prescribed to in our clinic, it did not always work well. We find that we still have to give the patient IV anti-emetics, even if they took Emend, because they still throw up. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Commenter: Takahashi, Gary Organization: Oregon Hematology Oncology Association Date: August 6, 2004 Comment: In my experience, Emend (aprepitant) is useful only as an adjunct to other antiemetics to prevent delayed-onset nausea and vomiting. It is only mildly effective when given alone, and must be combined with more potent anti-emetics to control acute-onset nausea. I recommend against using Emend as an oral substitute for drugs such as granisetron or palonosetron. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Commenter: D’Emanuele, Ross Organization: Dorsey & Whitney, LLP Date: August 6, 2004 Comment: Public Comment Offered in Response to CMS’ National Coverage Analysis (NCA) Titled “Aprepitant for Chemotherapy-Induced Emesis” (CAG-00248N) POSITION Oral EMEND® is not a replacement for any current commercially available intravenous antiemetic in the United States. Therefore, it is not appropriate to reimburse it as a Medicare Part B benefit. EMEND needs to be administered in conjunction with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and is not stand alone therapy. It does not function as a prodrug or have an IV equivalent. -

The Significance of NK1 Receptor Ligands and Their Application In

pharmaceutics Review The Significance of NK1 Receptor Ligands and Their Application in Targeted Radionuclide Tumour Therapy Agnieszka Majkowska-Pilip * , Paweł Krzysztof Halik and Ewa Gniazdowska Centre of Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry, Institute of Nuclear Chemistry and Technology, Dorodna 16, 03-195 Warsaw, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-22-504-10-11 Received: 7 June 2019; Accepted: 16 August 2019; Published: 1 September 2019 Abstract: To date, our understanding of the Substance P (SP) and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) system shows intricate relations between human physiology and disease occurrence or progression. Within the oncological field, overexpression of NK1R and this SP/NK1R system have been implicated in cancer cell progression and poor overall prognosis. This review focuses on providing an update on the current state of knowledge around the wide spectrum of NK1R ligands and applications of radioligands as radiopharmaceuticals. In this review, data concerning both the chemical and biological aspects of peptide and nonpeptide ligands as agonists or antagonists in classical and nuclear medicine, are presented and discussed. However, the research presented here is primarily focused on NK1R nonpeptide antagonistic ligands and the potential application of SP/NK1R system in targeted radionuclide tumour therapy. Keywords: neurokinin 1 receptor; Substance P; SP analogues; NK1R antagonists; targeted therapy; radioligands; tumour therapy; PET imaging 1. Introduction Neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R), also known as tachykinin receptor 1 (TACR1), belongs to the tachykinin receptor subfamily of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also called seven-transmembrane domain receptors (Figure1)[ 1–3]. The human NK1 receptor structure [4] is available in Protein Data Bank (6E59). -

World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines, 21St List, 2019

World Health Organizatio n Model List of Essential Medicines 21st List 2019 World Health Organizatio n Model List of Essential Medicines 21st List 2019 WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06 © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines, 21st List, 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris. -

Sertraline Film-Coated Tablets

Sertraline film-coated tablets 1.3 Product Information 1.3.1 SPC, labeling and package leaflet 1.3.1.3 Package leaflet Package leaflet is presented on subsequent pages: Module 1.3.1 Page 1 of 13 Sertraline film-coated tablets Package leaflet: Information for the user Sertraline 50 mg film coated tablets Sertraline 100 mg film coated tablets Sertraline Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Sertraline tablet is and what it is used for. 2. What you need to know before you take Sertraline tablets. 3. How to take Sertraline tablets. 4. Possible side effects. 5. How to store Sertraline tablets. 6. Contents of the pack and other information. 1. What Sertraline tablets is and what it is used for Sertraline tablet contains the active ingredient sertraline. Sertraline is one of a group of medicines called Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors (SSRIs); these medicines are used to treat depression and/or anxiety disorders. Sertraline tablets can be used to treat: Depression and prevention of recurrence of depression (in adults). -

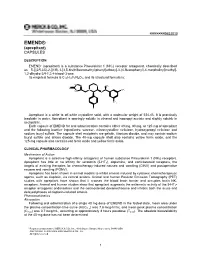

EMEND® (Aprepitant) CAPSULES

XXXXXXX9852010 EMEND® (aprepitant) CAPSULES DESCRIPTION * EMEND (aprepitant) is a substance P/neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonist, chemically described as 5-[[(2R,3S)-2-[(1R)-1-[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]ethoxy]-3-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-morpholinyl]methyl] 1,2-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazol-3-one. Its empirical formula is C23H21F7N4O3, and its structural formula is: NH N O CH3 O N CF3 NH O CF3 F Aprepitant is a white to off-white crystalline solid, with a molecular weight of 534.43. It is practically insoluble in water. Aprepitant is sparingly soluble in ethanol and isopropyl acetate and slightly soluble in acetonitrile. Each capsule of EMEND for oral administration contains either 40 mg, 80 mg, or 125 mg of aprepitant and the following inactive ingredients: sucrose, microcrystalline cellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose and sodium lauryl sulfate. The capsule shell excipients are gelatin, titanium dioxide, and may contain sodium lauryl sulfate and silicon dioxide. The 40-mg capsule shell also contains yellow ferric oxide, and the 125-mg capsule also contains red ferric oxide and yellow ferric oxide. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action Aprepitant is a selective high-affinity antagonist of human substance P/neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors. Aprepitant has little or no affinity for serotonin (5-HT3), dopamine, and corticosteroid receptors, the targets of existing therapies for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Aprepitant has been shown in animal models to inhibit emesis induced by cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin, via central actions. Animal and human Positron Emission Tomography (PET) studies with aprepitant have shown that it crosses the blood brain barrier and occupies brain NK1 receptors. -

Aprepitant and Fosaprepitant Drug Interactions: a Systematic Review Priya Patel1,2, J

Aprepitant and Fosaprepitant Drug Interactions: A Systematic Review Priya Patel1,2, J. Steven Leeder3,4, Micheline Piquette-Miller1, L. Lee Dupuis1,2,5 1Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2Department of Pharmacy, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 3Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Toxicology & Therapeutic Innovation, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy- Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, USA, 4School of Medicine, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, USA, 5Child Health Evaluative Sciences, Research Institute, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada OBJECTIVES BACKGROUND • To conduct a systematic review of the literature to determine if the • Aprepitant is recommended by clinical practice guidelines for the administration of aprepitant or fosaprepitant results in: prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting 1. A clinically significant change in the pharmacokinetic (PK) • Aprepitant and fosaprepitant are moderate and weak CYP3A4 disposition of a concomitant medication (i.e. a victim drug) inhibitors, respectively. Aprepitant is also a weak CYP2C9 inducer. 2. A clinically significant adverse event (AE) as a result of giving • There is no systematic literature review describing interactions another medication concomitantly between aprepitant or fosaprepitant and other drugs. METHODS RESULTS INFORMATION SOURCES: Figure 1. Study Identification Flow Diagram • Databases Searched (from inception to September 11, 2016): Ovid MEDLINE(R) -

Emerging Targets for Antidepressant Therapies Jeffrey J Rakofsky1, Paul E Holtzheimer2 and Charles B Nemeroff2

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Emerging targets for antidepressant therapies Jeffrey J Rakofsky1, Paul E Holtzheimer2 and Charles B Nemeroff2 Despite adequate antidepressant monotherapy, the majority of 70% of depressed patients have residual symptoms [3], depressed patients do not achieve remission. Even optimal and and, even with more aggressive therapies, 20% or more aggressive therapy leads to a substantial number of patients may show only a limited response [4]. Rather than being who show minimal and often only transient improvement. In the exception, recurrent episodes are the rule, and there order to address this substantial problem of treatment-resistant are few evidence-based approaches to help clinicians depression, a number of novel targets for antidepressant maintain a patient’s antidepressant response. Persistent therapy have emerged as a consequence of major advances in depression is associated with an increase in substance and the neurobiology of depression. Three major approaches to alcohol abuse, an increased risk for suicide and for car- uncover novel therapeutic interventions are: first, optimizing the diovascular disease. Thus, improved treatments for modulation of monoaminergic neurotransmission; second, depression are urgently needed. developing medications that act upon neurotransmitter systems other than monoaminergic circuits; and third, using Various forms of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and focal brain stimulation to directly modulate neuronal activity. electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are currently the most We review the most recent data on novel therapeutic commonly used antidepressant treatments. Serendipitous compounds and their antidepressant potential. These include discoveries and/or a limited understanding of the triple monoamine reuptake inhibitors, atypical antipsychotic neurobiology of depression which largely focused on the augmentation, and dopamine receptor agonists. -

Management of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome in Adults: Evidence Review

Title Page Management of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome in Adults: Evidence Review Ravi N. Sharaf1*, Thangam Venkatesan2*, Raj Shah3, David J. Levinthal4, Sally E. Tarbell5, Safwan S. Jaradeh6, William L. Hasler7, Robert M. Issenman8, Kathleen A. Adams9, Irene Sarosiek10, Christopher D. Stave11, B U.K. Li12, Shahnaz Sultan13 *These authors contributed equally. 1 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, New York; 2Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin; 3 Division of Gastroenterology and Liver Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio Cleveland, Ohio; 4Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; 5 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern Feinberg University School of Medicine; 6Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University Medical Center; 7 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School; 8 Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Department of Pediatrics, McMaster University; 9 Founder/President Emerita, Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Association; 10 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center; 11 Lane Medical Library, Stanford University; 12 Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin; -

Aprepitant for Refractory Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma-Associated Pruritus: 4 Cases and a Review of the Literature Johanna S

Song et al. BMC Cancer (2017) 17:200 DOI 10.1186/s12885-017-3194-8 CASE REPORT Open Access Aprepitant for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated pruritus: 4 cases and a review of the literature Johanna S. Song1,3,4, Marianne Tawa2, Nicole G. Chau3, Thomas S. Kupper1,2,4 and Nicole R. LeBoeuf1,2,4* Abstract Background: Aprepitant is an FDA-approved medication for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. It blocks substance P binding to neurokinin-1; substance P has been implicated in itch pathways both as a local and global mediator. Case presentations: We report a series of four patients, diagnosed with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, who experienced full body pruritus recalcitrant to standard therapies. All patients experienced rapid symptom improvement (within days) following aprepitant treatment. Conclusion: Aprepitant has been shown in small studies to be efficacious for treating chronic and malignancy-associated pruritus. Prior studies have shown no change in clinical efficacy of chemotherapeutics with concurrent aprepitant administration. These cases further demonstrate that aprepitant can be considered as a therapeutic option in malignancy-associated pruritus and further support the need for larger clinical trials. Keywords: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Aprepitant, Emend, Pruritus, Itch, Case report Background which was moderately responsive to prednisone. She had Aprepitant (Emend; Merck & Co Inc) has been approved previously been treated for her lymphoma with metho- for use as an antiemetic in patients receiving chemother- trexate and NB-UVB with no improvement in disease or apy. It blocks the binding of substance P to its receptor, itch. PUVA was tried and discontinued because of bullae neurokinin-1, which plays a role in pathways that induce development.