Vocal Behavior of Crested Guineafowl (Guttera Edouardi) Based on Visual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda: Shoebill, Albertine Rift Endemics, Green- Breasted Pitta, Gorillas and Chimpanzees Set Departure Trip Report

UGANDA: SHOEBILL, ALBERTINE RIFT ENDEMICS, GREEN- BREASTED PITTA, GORILLAS AND CHIMPANZEES SET DEPARTURE TRIP REPORT 1-19 AUGUST 2019 By Jason Boyce Yes, I know, it’s incredible! Shoebill from Mabamba Swamp, Uganda www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Uganda 2019 TOUR ITINERARY Overnight Day 1 – Introduction to Uganda’s birding, Entebbe Entebbe Day 2 – Mabamba Swamp and Lake Mburo National Park Lake Mburo Day 3 – Lake Mburo National Park Lake Mburo Day 4 – Mgahinga Gorilla National Park Kisoro Day 5 – Mgahinga Gorilla National Park Kisoro Day 6 – Transfer to Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, Ruhija Ruhija Day 7 – Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, Ruhija Ruhija Day 8 – Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, Buhoma Buhoma Day 9 – Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, Buhoma Buhoma Day 10 – Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, Buhoma Buhoma Day 11 – Transfer to Queen Elizabeth National Park Mweya Day 12 – Queen Elizabeth National Park to Kibale National Park Kibale Day 13 – Kibale National Park Kibale Day 14 – Kibale to Masindi Masindi Day 15 – Masindi, Budongo Forest Masindi Day 16 – Masindi to Murchison Falls National Park Murchison Falls Day 17 – Murchison Falls National Park Murchison Falls Day 18 – Transfer to Entebbe Entebbe Day 19 – International Flights Overview Interestingly enough this was one of the “birdier” Uganda tours that I have been on. Birds were generally in good voice, and fair numbers of birds were seen at most of our hotspots. Cuckoos were a little less vocal, but widowbirds, bishops, and weavers were in full breeding plumage and displaying all over the place. -

Do Large Birds Experience Previously Undetected Levels of Hunting Pressure in the Forests of Central and West Africa?

Do large birds experience previously undetected levels of hunting pressure in the forests of Central and West Africa? R OBIN C. WHYTOCK,RALPH B UIJ,MUNIR Z. VIRANI and B ETHAN J. MORGAN Abstract The commercial bushmeat trade threatens Introduction numerous species in the forests of West and Central Africa. Hunters shoot and trap animals, which are trans- umans have hunted for subsistence in the forests ported to rural and urban markets for sale. Village-based Hof Central and West Africa for millennia (Milner- 2003 surveys of hunter offtake and surveys of bushmeat markets Gulland et al., ). However, for many people living in have shown that mammals and reptiles are affected most, rural areas hunting has become an important source of followed by birds. However, hunters also consume some revenue, driven by the high demand for bushmeat among 2003 2005 animals in forest camps and these may have been over- urban populations (Fa et al., ; East et al., ). The looked in surveys that have focused on bushmeat extracted commercial bushmeat trade has become central to many fi from the forest. A number of studies have used indirect rural economies and a signi cant proportion of households methods, such as hunter diaries, to quantify this additional rely on hunting as their primary source of income (Wilkie & 1999 offtake but results can be difficult to verify. We examined Carpenter, ). The problem has been further exacerbated discarded animal remains at 13 semi-permanent hunting by the construction of roads for commercial logging op- camps in the Ebo Forest, Cameroon, over 272 days. Twenty- erations, which have made it easier to access previously one species were identified from 49 carcasses, of which birds unexploited wildlife populations and to transport meat to 2003 constituted 55%, mammals 43% and other taxa 2%. -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves. -

Uganda Highlights

UGANDA HIGHLIGHTS JANUARY 11–30, 2020 “Mukiza” the Silverback, Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, January 2020 ( Kevin J. Zimmer) LEADERS: KEVIN ZIMMER & HERBERT BYARUHANGA LIST COMPILED BY: KEVIN ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM UGANDA HIGHLIGHTS January 11–30, 2020 By Kevin Zimmer Shoebill, Mabamba wetlands, January 2020 ( Kevin J. Zimmer) This was the second January departure of our increasingly popular Uganda Highlights Tour, and it proved an unqualified success in delivering up-close-and-personal observations of wild Mountain Gorillas, wild Chimpanzees, and the bizarre Shoebill. Beyond these iconic creatures, we racked up over 430 species of birds and had fabulous encounters with Lion, Hippopotamus, African Elephant, Rothschild’s Giraffe, and an amazing total of 10 species of primates. The “Pearl of Africa” lived up to its advance billing as a premier destination for birding and primate viewing in every way, and although the bird-species composition and levels of song/breeding activity in this (normally) dry season are somewhat different from those encountered during our June visits, the overall species diversity of both birds and mammals encountered has proven remarkably similar. After a day at the Boma Hotel in Entebbe to recover from the international flights, we hit the ground running, with a next-morning excursion to the fabulous Mabamba wetlands. Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Uganda Highlights, January 2020 Opportunistic roadside stops en route yielded such prizes as Great Blue Turaco, Lizard Buzzard, and Black-and-white-casqued Hornbill, but as we were approaching the wetlands, the dark cloud mass that had been threatening rain for the past hour finally delivered. -

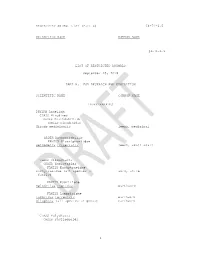

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Additional Records of Avian Egg Teeth Kenneth C

ADDITIONAL RECORDS OF AVIAN EGG TEETH KENNETH C. PARKES AND GEORGEA. CLARK, JR. N an admittedly preliminary survey (Clark, 1961)) the junior author listed I 46 families of birds for which he had found records of the presence in hatchlings or embryos of an egg tooth on the upper mandible. In five addi- tional families (Haematopodidae, Charadriidae, Recurvirostridae, Burhinidae, Bucerotidae), egg teeth or analogous structures had been reported as having been found on the lower jaw only. The 1961 paper was based primarily on an extensive but by no means exhaustive survey of the literature, supplemented by examination of specimens at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. In connection with a study of early plumages of birds, we have had oc- casion to handle several hundred additional specimens, both study skins and alcoholics, and have taken advantage of this opportunity to record additional data on egg teeth. The principal collections utilized were those of the American Museum of Natural History (hereinafter abbreviated as AMNH), Chicago Natural History Museum, Carnegie Museum (CM), and Yale Peabody Museum. Parkes examined certain additional specimens in the collections of the United States National Museum (USNM) , University of California (both Berkeley and Los Angeles), the California Academy of Sciences, and Cornell University (CU) . Unless otherwise specified, records of egg teeth in the following list are based on specimens examined by one or both of us. Also included are addi- tional literature records, both prior and subsequent to Clarks’ 1961 paper. Families not previously reported by Clark as having egg teeth on the upper mandible are starred (“) ; there are 51 such additional family records in- cluded in the present paper. -

Functional Correlation Between Habitat Use and Leg Morphology in Birds (Aves)

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4066The Linnean Society of London, 2003? 2003 79? Original Article HABITAT and LEG MORPHOLOGY IN BIRDS ( AVES )A. ZEFFER ET AL. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2003, 79, 461–484. With 9 figures Functional correlation between habitat use and leg morphology in birds (Aves) ANNA ZEFFER, L. CHRISTOFFER JOHANSSON* and ÅSA MARMEBRO Department of Zoology, Göteborg University, Box 463, SE 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Received 17 May 2002; accepted for publication 12 December 2002 Many of the morphological features of animals are considered to be adaptations to the habitat that the animals uti- lize. The habitats utilized by birds vary, perhaps more than for any other group of vertebrates. Here, we study pos- sible adaptations in the morphology of the skeletal elements of the hind limbs to the habitat of birds. Measurements of the lengths of the femur, tibiotarsus and tarsometatarsus of 323 bird species from 74 families are used together with body mass data, taken from the literature. The species are separated into six habitat groups on the basis of lit- erature data on leg use. A discriminant analysis of the groups based on leg morphology shows that swimming birds, wading birds and ground living species are more easily identified than other birds. Furthermore, functional predic- tions are made for each group based on ecological and mechanical considerations. The groups were tested for devi- ation from the norm for all birds for three indices of size- and leg-length-independent measures of the bones and for a size-independent-index of leg length. -

A Multigene Phylogeny of Galliformes Supports a Single Origin of Erectile Ability in Non-Feathered Facial Traits

J. Avian Biol. 39: 438Á445, 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.2008.0908-8857.04270.x # 2008 The Authors. J. Compilation # 2008 J. Avian Biol. Received 14 May 2007, accepted 5 November 2007 A multigene phylogeny of Galliformes supports a single origin of erectile ability in non-feathered facial traits Rebecca T. Kimball and Edward L. Braun R. T. Kimball (correspondence) and E. L. Braun, Dept. of Zoology, Univ. of Florida, P.O. Box 118525, Gainesville, FL 32611 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Many species in the avian order Galliformes have bare (or ‘‘fleshy’’) regions on their head, ranging from simple featherless regions to specialized structures such as combs or wattles. Sexual selection for these traits has been demonstrated in several species within the largest galliform family, the Phasianidae, though it has also been suggested that such traits are important in heat loss. These fleshy traits exhibit substantial variation in shape, color, location and use in displays, raising the question of whether these traits are homologous. To examine the evolution of fleshy traits, we estimated the phylogeny of galliforms using sequences from four nuclear loci and two mitochondrial regions. The resulting phylogeny suggests multiple gains and/or losses of fleshy traits. However, it also indicated that the ability to erect rapidly the fleshy traits is restricted to a single, well-supported lineage that includes species such as the wild turkey Meleagris gallopavo and ring-necked pheasant Phasianus colchicus. The most parsimonious interpretation of this result is a single evolution of the physiological mechanisms that underlie trait erection despite the variation in color, location, and structure of fleshy traits that suggest other aspects of the traits may not be homologous. -

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines for Turacos (Musophagidae)

EAZA BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES EAZA Toucan & Turaco TAG TURACOS Musophagidae 1st Edition Compiled by Louise Peat 2017 1 | P a g e Front cover; Lady Ross’s chick. Photograph copyright of Eric Isselée-Life on White, taken at Mulhouse zoo. http://www.lifeonwhite.com/ http://www.zoo-mulhouse.com/ Author: Louise Peat. Cotswold Wildlife Park Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Toucan & Turaco TAG TAG Chair: Laura Gardner E-mail: [email protected] 2 | P a g e EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright 2017 by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Toucan & Turaco TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

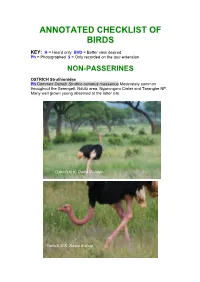

Annotated Checklist of Birds

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF BIRDS KEY: H = Heard only BVD = Better view desired Ph = Photographed $ = Only recorded on the tour-extension NON-PASSERINES OSTRICH Struthionidae Ph Common Ostrich Struthio camelus massaicus Moderately common throughout the Serengeti, Ndutu area, Ngorongoro Crater and Tarangire NP. Many well grown young observed at the latter site. Ostrich © K. David Bishop Ostrich © K. David Bishop DUCKS, GEESE & WATERFOWL Anatidae Ph White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna guttata 1-2 on two days along the shores of Lake Victoria at Speke Bay Lodge; four on backwaters, Lake Manyara NP and a total of circa 15 at the Mombo wetland. White-faced Whisting-Duck © K. David Bishop $ Fulvous Whistling- Duck Dendrocygna bicolor One at the Mombo wetlands. Comb Duck Sarkidiornis m. melanotos 40+ at Lake Manyara NP; ten in wetlands between Lake Manyara and Tarangire NP and 1-2 daily along the river, Tarangire NP Ph Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca Widespread and moderately common: Arsuha NP; Lake Victoria; Serengeti; Ngorongoro where as many as 100+ counted including a group of ten chicks at the margins of Lake Makta and Tarangire NP. Egyptian Goose © K. David Bishop Ph Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus g. gambensis A total of seven on a freshwater swamp within the Ngorongoro Crater. Ph African Black Duck Anas sparsa leucostigma Two pairs seen very nicely in the grounds of Negare Sero Lodge; two on a freshwater within the Ngorongoro Crater and one in the West Usambaras. African Black Duck © David Bishop Red-billed Duck (Teal) Anas erythrorhyncha Small numbers in the Serengeti, Lake Manyara and ten at the Mombo wetland. -

SOUTH AFRICA: LAND of the ZULU 26Th October – 5Th November 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 A Tropical Birding CUSTOM tour SOUTH AFRICA: LAND OF THE ZULU th th 26 October – 5 November 2015 Drakensberg Siskin is a small, attractive, saffron-dusted endemic that is quite common on our day trip up the Sani Pass Tour Leader: Lisle Gwynn All photos in this report were taken by Lisle Gwynn. Species pictured are highlighted RED. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 INTRODUCTION The beauty of Tropical Birding custom tours is that people with limited time but who still want to experience somewhere as mind-blowing and birdy as South Africa can explore the parts of the country that interest them most, in a short time frame. South Africa is, without doubt, one of the most diverse countries on the planet. Nowhere else can you go from seeing Wandering Albatross and penguins to seeing Leopards and Elephants in a matter of hours, and with countless world-class national parks and reserves the options were endless when it came to planning an itinerary. Winding its way through the lush, leafy, dry, dusty, wet and swampy oxymoronic province of KwaZulu-Natal (herein known as KZN), this short tour followed much the same route as the extension of our South Africa set departure tour, albeit in reverse, with an additional focus on seeing birds at the very edge of their range in semi-Karoo and dry semi-Kalahari habitats to add maximum diversity. KwaZulu-Natal is an oft-underrated birding route within South Africa, featuring a wide range of habitats and an astonishing diversity of birds. -

Fire and Animal Behavior

Proceedings: 9th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1969 Komarek, E.v. 1969. Fire and animal behavior. Pages 160-207 in E.V. Komarek (conference chariman). Proceedings Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: No.9. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. 9. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL. Fire and Animal Behavior E. V. KOMAREK, SR. Tall Ti'mbers Researcb Station Tallabassee, Florida , THE REACTIONS and relationships of animals to fire, the charcoal black burn, the straw-colored and later the green vegetation certainly attracted the attention of primitive man and his ancestors. In "Fire-and the Ecology of iV'lan" I proposed that man himself is the product of a fire environment-"pre-'man prirrtates as well as early Ulan inhabited fire environrnents and had to be 'fire selected' ... to live in such environments." (Komarek, 1967). Therefore, man's ultimate survival, as had been true with other ani mals that live in fire environments, depends upon a proper under standing of fire and the relationships of animals and plants to this element. 1V10dern literature, particularly in the United States, has been so saturated with the reputed dangers of forest fires to animals that he has developed a deep seated fear of all fires in nature. In this nation, the average individual is only beginning to realize the proper place of fire and fire control in forest, grassland and field. Unfortunately, much knowledge on fire and animal behavior that was common in formation to the American Indian, pioneers, and early farm and ranch people has been lost though in some parts of the ·world a large body of this knowledge still exists.