Three Schools of Thought About Learning and Teaching © Syda Productions/Shutterstock.Com © Syda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Norms and Social Influence Mcdonald and Crandall 149

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Social norms and social influence Rachel I McDonald and Christian S Crandall Psychology has a long history of demonstrating the power and and their imitation is not enough to implicate social reach of social norms; they can hardly be overestimated. To norms. Imitation is common enough in many forms of demonstrate their enduring influence on a broad range of social life — what creates the foundation for culture and society phenomena, we describe two fields where research continues is not the imitation, but the expectation of others for when to highlight the power of social norms: prejudice and energy imitation is appropriate, and when it is not. use. The prejudices that people report map almost perfectly onto what is socially appropriate, likewise, people adjust their A social norm is an expectation about appropriate behav- energy use to be more in line with their neighbors. We review ior that occurs in a group context. Sherif and Sherif [8] say new approaches examining the effects of norms stemming that social norms are ‘formed in group situations and from multiple groups, and utilizing normative referents to shift subsequently serve as standards for the individual’s per- behaviors in social networks. Though the focus of less research ception and judgment when he [sic] is not in the group in recent years, our review highlights the fundamental influence situation. The individual’s major social attitudes are of social norms on social behavior. formed in relation to group norms (pp. 202–203).’ Social norms, or group norms, are ‘regularities in attitudes and Address behavior that characterize a social group and differentiate Department of Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045, it from other social groups’ [9 ] (p. -

Problem Solving and Learning

Science Watch Problem Solving and Learning John R. Anderson Newell and Simon (1972) provided a framework for un- computer simulation of human thought and was basically derstanding problem solving that can provide the needed unconnected to research in animal and human learning. bridge between learning and performance. Their analysis Research on human learning and research on prob- of means-ends problem solving can be viewed as a general lem solving are finally meeting in the current research characterization of the structure of human cognition. on the acquisition of cognitive skills (Anderson, 1981; However, this framework needs to be elaborated with a Chi, Glaser, & Farr, 1988; Van Lehn, 1989). Given nearly strength concept to account for variability in problem- a century of mutual neglect, the concepts from the two solving behavior and improvement in problem-solving skill fields are ill prepared to relate to each other. I will argue with practice. The ACT* theory (Anderson, 1983) is such in this article that research on human problem solving an elaborated theory that can account for many of the would have been more profitable had it attempted to in- results about the acquisition of problem-solving skills. Its corporate ideas from learning theory. Even more so, re- central concept is the production rule, which plays an search on learning would have borne more fruit had analogous role to the stimulus-response bond in earlier Thorndike not cast out problem solving. learning theories. The theory has provided a basis for con- This article will review the basic conception of prob- structing intelligent computer-based tutoring systems for lem solving that is the legacy of the Newell and Simon the instruction of academic problem-solving skills. -

Teacher Training: Learning to Be Instigators of Thought™ Through a Process Aligned with Inspired Teaching's Educational Phil

Transforming education through innovation teacher training Teacher Training: Learning to be Instigators of Thought™ Through a process aligned with Inspired Teaching’s educational philosophy – which engages participants intellectually, physically, and emotionally - Inspired Teaching trains teachers to design and implement rigorous, student-centered lessons and activities that meet student needs and academic standards, including the Common Core State Standards. Like the teaching process itself, our teacher training is complex and allows for customization to meet the specific needs of each teacher. This audience-sensitivity creates a permanent shift in teachers’ thinking about their jobs and is one of the key reasons our process is so effective. Inspired Teaching’s Five Step Process for Teacher Education Each teacher navigates the following process: Step 1. Analyze and deepen my understanding of the ways I learn through a rigorous examination of the teaching and learning process, including my including my own experiences as a child and adult learner. Step 2. Articulate and defend my philosophy of teaching and learning , including what I believe about children. Challenge myself to listen to and consider other points of view and to find room in my philosophy for an appreciation of children's natural curiosity and innate desire to learn. Step 3. Make the connection to classroom practice , analyzing my current instructional strategies and whether they support my philosophy, so that I can explore and develop new ways to make sure what I do in the classroom matches my philosophy of teaching and learning. Step 4. Build the skills of effective teachers , including active listening, asking questions that will spark students' intellect and imaginations, observing to assess for student understanding, and communicating effectively. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

The Role of Emotion and Skilled Intuition in Learning

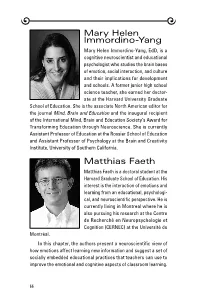

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, EdD, is a cognitive neuroscientist and educational psychologist who studies the brain bases of emotion, social interaction, and culture and their implications for development and schools. A former junior high school science teacher, she earned her doctor- ate at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education. She is the associate North American editor for the journal Mind, Brain and Education and the inaugural recipient of the International Mind, Brain and Education Society’s Award for Transforming Education through Neuroscience. She is currently Assistant Professor of Education at the Rossier School of Education and Assistant Professor of Psychology at the Brain and Creativity Institute, University of Southern California. Matthias Faeth Matthias Faeth is a doctoral student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. His interest is the interaction of emotions and learning from an educational, psychologi- cal, and neuroscientific perspective. He is currently living in Montreal where he is also pursuing his research at the Centre de Recherché en Neuropsychologie et Cognition (CERNEC) at the Université de Montréal. In this chapter, the authors present a neuroscientific view of how emotions affect learning new information and suggest a set of socially embedded educational practices that teachers can use to improve the emotional and cognitive aspects of classroom learning. 66 Chapter 4 The Role of Emotion and Skilled Intuition in Learning Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and Matthias Faeth Advances in neuroscience have been increasingly used to inform educational theory and practice. However, while the most successful strides forward have been made in the areas of academic disciplinary skills such as reading and mathematical processing, a great deal of new evidence from social and affective neuroscience is prime for application to education (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007; Immordino-Yang & Fischer, in press). -

Full-Day Kindergarten: a Missing Link in the Prekindergarten Through Third Grade (P-3) Continuum for Many Students

BACKGROUNDER: Full-day Kindergarten: A Missing Link in the Prekindergarten through Third Grade (P-3) Continuum for Many Students ull-day kindergarten provides an essential bridge Too Few States Require Districts to Offer Fbetween prekindergarten (preK) and the primary Full-day Kindergarten grades. In kindergarten classrooms, students develop the academic, social, and emotional skills they need to ``Currently, only 11 states and the District of be successful later in school. These benefits seem to be Columbia require districts to offer at least five hours greater for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. of kindergarten per day.1 However, far too many children have no access to full- ``Forty-five states require that school districts provide day kindergarten, and not enough has been done in the at least half-day kindergarten. last decade to provide more children with access to this `` critical link between early childhood and K-12 education. There are five states that do not require districts to offer any type of kindergarten program, although many school districts offer half-day kindergarten Why is Full-day Kindergarten Important? at a minimum. ``Thirty-five states do not require children to attend In recent years, state and federal initiatives have greatly kindergarten. expanded access to prekindergarten programs for three- and four-year-old children. This expansion provides many more children with access to high-quality, full-day, The Amount of Instructional Time Students and often, full-year preK programs. Unfortunately, too Receive in Full-day Kindergarten Matters many children will follow full-day preK with half-day kindergarten which may jeopardize the important As in all grades, the amounts of instructional time academic and social gains made in preK. -

What to Expect... Education & Training Career Cluster

HEAR FROM PROFESSIONALS. LEARN FROM EXPERIENCE. EDUCATION & TRAINING CAREER CLUSTER NEBRASKA CAREER TOURS WHAT TO EXPECT... INTERVIEWS Each video contains interviews with employees and business representatives discussing work requirements, education levels, salary and job prospects. TOURS Experience virtual industry tours that provide a unique opportunity to get a glimpse inside Nebraska-based companies without leaving your home or classroom. INFORMATION Throughout the videos you will find valuable information regarding job markets, sal- aries, and educational requirements to help you identify a possible career path. TEACHER DISCUSSION GUIDE www.necareertours.com HEAR FROM PROFESSIONALS. LEARN FROM EXPERIENCE. NEBRASKA CAREER TOURS EDUCATION AND TRAINING This cluster prepares for careers in providing, supporting, and managing the education and training of millions of learners. It encompasses ages from pre- school through adults; varies from informal to formal settings; and provides for the skills necessary for initial entrance as well as updating skills to advance within the job or train for a different one. TEACHER DISCUSSION GUIDE www.necareertours.com NOTE TO INSTRUCTOR: Below are suggested activities and questions to accompany the virtual industry tour. Each component may be used individually or modified to fit the needs of your classroom. For more information on this Career Cluster, visit these websites: • www.education.ne.gov/nce/CareerClustersResources.html • h3.ne.gov/H3/ • www.nebraskacareerconnections.org In addition, NEworks has an array of resources, including Nebraska Workforce Trends magazine, Labor Market Regional Reviews, Occupational Profiles and Career Ladder Posters, available at https://www.neworks.nebraska.gov under Labor Market Information, Publications. BELL RINGER: Post the following prompt on a writing surface for students to answer as they enter the room. -

Comment Fundamentalism and Science

SISSA – International School for Advanced Studies Journal of Science Communication ISSN 1824 – 2049 http://jcom.sissa.it/ Comment Fundamentalism and science Massimo Pigliucci The many facets of fundamentalism. There has been much talk about fundamentalism of late. While most people's thought on the topic go to the 9/11 attacks against the United States, or to the ongoing war in Iraq, fundamentalism is affecting science and its relationship to society in a way that may have dire long-term consequences. Of course, religious fundamentalism has always had a history of antagonism with science, and – before the birth of modern science – with philosophy, the age-old vehicle of the human attempt to exercise critical thinking and rationality to solve problems and pursue knowledge. “Fundamentalism” is defined by the Oxford Dictionary of the Social Sciences 1 as “A movement that asserts the primacy of religious values in social and political life and calls for a return to a 'fundamental' or pure form of religion.” In its broadest sense, however, fundamentalism is a form of ideological intransigence which is not limited to religion, but includes political positions as well (for example, in the case of some extreme forms of “environmentalism”). In the United States, the main version of the modern conflict between science and religious fundamentalism is epitomized by the infamous Scopes trial that occurred in 1925 in Tennessee, when the teaching of evolution was challenged for the first time 2,3. That battle is still being fought, for example in Dover, Pennsylvania, where at the time of this writing a court of law is considering the legitimacy of teaching “intelligent design” (a form of creationism) in public schools. -

Bias and Critical Thinking

BIAS AND CRITICAL THINKING Point: there is an alternative to • being “biased” (one-sided, closed-minded, etc.) • simply having an “opinion” (by which I mean a viewpoint that has subjective value only: “everyone has their own opinions”) • being neutral and not taking a position In thinking about bias, it is important to distinguish between four things: 1. a particular position taken on an issue 2. the source of that position (its support and basis) 3. the resistance or openness to other positions 4. the impact that position has on other positions and viewpoints taken by the person Too often, people confuse these four. One result is that people sometimes assume that taking any position on an issue (#1) is an indication of bias. If this were true, then the only way to avoid bias would be to not take a position but rather simply present what are considered to be facts. In this way one is supposedly “objective” and “neutral.” However, it is highly debatable whether one can really be objective and neutral or whether one can present objective facts in a completely neutral way. More importantly, there are two troublesome implications of such a viewpoint on bias: • the ideal would seem to be not taking a position (but to really deal with issues we have to take a position) • all positions are biased and therefore it is difficult if not impossible to judge one position superior to another. It is far better to reject the idea that taking any position always implies bias. Rather, bias is a function either of the source of that position, or the resistance one has to other positions, or the impact that position has on other positions and viewpoints taken. -

Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln July 2005 Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information Ken R. Herold Hamilton College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Herold, Ken R., "Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information" (2005). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/27 Library Philosophy and Practice Vol. 3, No. 2 (Spring 2001) (www.uidaho.edu/~mbolin/lppv3n2.htm) ISSN 1522-0222 Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information Ken R. Herold Systems Manager Burke Library Hamilton College Clinton, NY 13323 “My purpose is to tell of bodies which have been transformed into shapes of a different kind.” Ovid, Metamorphoses Part I. Library Philosophy Provocation Information seems to be ubiquitous, diaphanous, a-categorical, discrete, a- dimensional, and knowing. · Ubiquitous. Information is ever-present and pervasive in our technology and beyond in our thinking about the world, appearing to be a generic ‘thing’ arising from all of our contacts with each other and our environment, whether thought of in terms of communication or cognition. For librarians information is a universal concept, at its greatest extent total in content and comprehensive in scope, even though we may not agree that all information is library information. · Diaphanous. Due to its virtuality, the manner in which information has the capacity to make an effect, information is freedom. In many aspects it exhibits a transparent quality, a window-like clarity as between source and patron in an ideal interface or a perfect exchange without bias. -

Meaningful Learning CHAPTER 1 Shutterstock

M01_HOWL5585_04_SE_C01.qxd 2/11/11 10:00 PM Page 1 Goal of Technology Integrations: Meaningful Learning CHAPTER 1 Shutterstock Chapter Objectives 1. Identify the characteristics of meaningful learning 4. Describe how technology can foster 21st Century Skills 2. Contrast learning from technology and learning with technology 5. Describe the components of technological pedagogical content knowledge 3. Compare National Educational Technology Standards (NETS) for students with teacher activities that foster them M01_HOWL5585_04_SE_C01.qxd 2/11/11 10:00 PM Page 2 2 Chapter 1 This edition of Meaningful Learning with Technology is one of many books describing how technologies can and should be used in schools. What distinguishes this book from the oth- ers is our focus on learning, especially meaningful learning. Most of the other books are organized by technology. They provide advice on how to use technologies, but often the purpose for using those technologies is not explicated. Meaningful Learning with Technology, on the other hand, is organized by kinds of learning. What drives learning, more than anything else, is understanding and persisting on some task or activity. The nature of the tasks best determines the nature of the students’ learning. Unfortunately, the nature of the tasks that so many students most commonly experience in schools is completing standardized tests or memorizing infor- mation for teacher-constructed tests. Schools in the United States have become testing factories. Federal legislation (No Child Left Behind) has mandated continuous testing of K–12 students in order to make schools and students more accountable for their learn- ing. In order to avoid censure and loss of funding, many K–12 schools have adopted test preparation as their primary curriculum. -

Idealism and Realism in Western and Indian Philosophies

IDEALISM AND REALISM IN WESTERN AND INDIAN PHILOSOPHIES —Dr. Sohan Raj Tater Over the centuries the philosophical attitude in the west has never been constant but undulated between Idealism and Realism. The difference between these two appears to be irreconcilable, being more or less bound up with the innate difference of predispositions and tendencies varying from person to person. The result is an uncompromising antagonism. The western scholars, who were brought up in the tradition of Kant and Hegel, and who studied Indian philosophies, were more sympathetic towards the Idealistic systems of India. In the 19 th century, there was a predominant wave of monism and scholars like Max Muller were naturally attracted towards the metaphysical views of Sankara etc. and the uncompromising Monism of Vedanta was much admired as the cream of the oriental wisdom. There have been different Idealistic views in Western and Indian philosophies as follows : Western Idealism (i) Platonic Idealism The Idealism of Plato is objective in the sense that the ideas enjoy an existence in a real world independent of any mind. Mind is not antecedent for the existence of ideas. The ideas are there whether a mind reveals them or not. The determination of the phenomenal world depends on them. They somehow determine the empirical existence of the world. Hence, Plato’s conception of reality is nothing but a system of eternal, immutable and immaterial ideas. (ii) Idealism of Berkeley Berkeley may be said to be the founder of Idealism in the modern period, although his arrow could not touch the point of destination.