Student Perceptions of E-Assessment Tools for Sign Language Interpretation Marc Boese Walden University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Electronic Assessment Portfolios

Introduction to Electronic Assessment Portfolios Teacher portfolios: The process of developing electronic portfolios can document evidence of teacher competencies and guide long-term professional development. The competencies may be locally defined, or linked to national teaching standards. Two primary assumptions in this process are: 1.) a portfolio is not a haphazard collection of artifacts (i.e., a scrapbook) but rather a reflective tool which demonstrates growth over time; and 2.) as we move to more standards-based teacher performance assessment, we need new tools to record and organize evidence of successful teaching, for both practicing professionals and student teachers. Student portfolios: One of the most exciting developments in the school reform movement is the use of alternative forms of assessment to evaluate student learning, and one of the most popular forms of authentic assessment is the use of portfolios. The point of the portfolio (electronic or paper) is to provide a "richer picture" of a student's abilities, and to show growth over time. Portfolios are being developed at all phases of the life span, beginning in early childhood, through K-12 and higher education, to professional teaching portfolios. As more schools expand student access to technology, there are an increasing number of options available for developing electronic student portfolios, including relational databases, hypermedia programs, WWW pages, PDF files, and commercial proprietary programs. Electronic portfolios: Electronic portfolio development draws on two bodies of literature: multimedia development (decide, design, develop, evaluate) (Ivers & Barron, 1998) and portfolio development (collection, selection, reflection, projection) (Danielson & Abrutyn, 1997). Both processes are complimentary and essential for effective electronic portfolio development. -

Towards a Research Agenda on Computer-Based

TOWARDS A RESEARCH AGENDA ON COMPUTER-BASED ASSESSMENT Challenges and needs for European Educational Measurement Friedrich Scheuermann & Angela Guimarães Pereira (Eds.) EUR 23306 EN - 2008 The Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen provides research-based, systems- oriented support to EU policies so as to protect the citizen against economic and technological risk. The Institute maintains and develops its expertise and networks in information, communication, space and engineering technologies in support of its mission. The strong cross- fertilisation between its nuclear and non-nuclear activities strengthens the expertise it can bring to the benefit of customers in both domains. European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen Contact information Address: Unit G09, QSI / CRELL TP-361, Via Enrico Fermi, 2749; 21027 Ispra (VA), Italy E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Tel.: +39-0332-78.6111 Fax: +39-0332-78.5733 http://ipsc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ http://www.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ Legal Notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server http://europa.eu/ JRC44526 EUR 23306 EN ISSN 1018-5593 Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities © European Communities, 2008 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Italy Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………... -

E-Lev: Solution for Early Childhood Education Teachers in Industrial Revolution Era 4.0

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 387 3rd International Conference on Education Innovation (ICEI 2019) E-LEv: Solution for Early Childhood Education Teachers in Industrial Revolution Era 4.0 Prima Suci Rohmadheny, Avanti Vera Risti Pramudyani Teacher Training of Early Childhood Education Universitas Ahmad Dahlan Yogyakarta, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Early Childhood Education (ECE) learning administration, scoring, and its interpretation. It was the evaluation refers to the evaluation of early aged-children' competence in communicating the result of the assessment developmental achievement. This is pivotal to measure that becomes the problem faced by the teachers there [6]. It is developmental achievement during and after the learning activity different from what happens in Indonesia. is conducted. From the previous study shown that teacher faced The empirical fact proves that the learning assessment and various problems to do assessment and evaluation. Accordingly, this study aimed to explore the ECE teachers' need to find evaluation in ECE are still sub-optimal; it was due to various solutions for the problems. The data were collected using a problems faced by the ECE teacher. This fact is supported by questionnaire distributed randomly in Indonesia through google the result of the preliminary study conducted by the form. The data were analyzed in accordance with the Miles and researchers. The preliminary study found various problems Hubberman analysis model. The data were presented such as teachers who perceive that learning assessment and descriptively to clear up the finding of the study. The study found evaluation in Indonesia is time-consuming. While, the teachers that (a) the majority of teachers had made attempts to improve are responsible for a vast amount of duties. -

Electronic Evaluation: Facts, Challenges and Expectations

The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education - Ocrober 2019 Volume 9, Issue 4 ELECTRONIC EVALUATION: FACTS, CHALLENGES AND EXPECTATIONS Aissa HANIFI Chlef University ,Algeria, Algeria , Relizane , 48011 [email protected] & [email protected] ABSTRACT Due to its fundamental role in the teaching and learning process, the concept of evaluation has been widely tackled in academic spheres. As a matter of fact, evaluation can help us discriminate between good and bad courses and thus establishes a solid background for setting success to major courses’ aims and outcomes. Whether in electronic or paper form and whether as a continuous or periodic process, evaluation helps teachers to form judgement values and students’ development and achievements. With regard to electronic evaluation, more and more university Algerian teachers are performing it though with a low degree through the online Master and Doctorate theses works’ supervision, for instance .The current study aims at investigating the teachers’ attitude to the use of electronic evaluation as a means to evaluate students’ performance and progress. The other aim is also to shed light on other aspects of electronic evaluation which are still under limited experimental process and needs to be upgraded in the university departments’ database. This might include mainly the electronic course evaluation system and course work assignment electronic submission. Results which were collected through an online survey submitted in the form of Likert scale questionnaire to 16 teachers randomly selected across different Algerian universities revealed interesting findings. Most teachers agreed that electronic evaluation system can replace paper evaluation system forms since it saves much of the teacher’s time and energy. -

Tools and Possibilities for Electronic Assessment in Higher Education

E-ASSESSMENT: TOOLS AND POSSIBILITIES FOR ELECTRONIC ASSESSMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION P. Miranda1, P. Isaias2, S. Pifano3 1Research Center for Engineering a Sustainable Development (Sustain. RD-IPS) Setubal School of Technology, Polytechnic Institute of Setubal (PORTUGAL) 2Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation (ITaLI) and UQ Business School, The University of Queensland (AUSTRALIA) 3ISR Lab – Information Society Research Lab (PORTUGAL) Abstract Technology deployment in higher education is at a thriving stage, with an increasing number of institutions embracing the possibilities afforded by technological tools and a mounting interest from teachers who are becoming more familiar with the intricacies of technology. There are several aspects of higher education that have been digitalised and transformed by the constant technological advancements of key tools for learning. Assessment, as an integral part of learning, has also been adopting a growing number and variety of tools to assist the measurement of the learning outcomes of the students. This paper intends to examine the technology that is available to develop effective e- assessment practices. It reviews key literature about the use of technology to develop assessment in higher education to provide a comprehensive account of the tools that teachers can use to assist the assessment of their students’ learning outcomes. The e-assessment instruments that are presented in this paper have different degrees of complexity, ranging from simple e-exams to the use of complete gamified learning and assessment experiences. They represent varied solutions that can be adapted to an ample assortment of assessment scenarios and needs, and they extend the possibilities of assessment far beyond the limits of conventional grading, offering a more current and more adequate answer to the demands of the contemporary higher education sector. -

Electronic Assessment and Feedback Tool in Supervision of Nursing Students During Clinical Training

Electronic Assessment and Feedback Tool in Supervision of Nursing Students During Clinical Training Sari Mettiäinen Tampere University of Applied Sciences, Finland [email protected] Abstract: The aim of this study was to determine nursing teachers’ and students’ attitudes to and experiences of using an electronic assessment and feedback tool in supervision of clinical training. The tool was called eTaitava, and it was developed in Finland. During the pilot project, the software was used by 12 nursing teachers and 430 nursing students. Nine of the teachers participated in the interviews and survey, and 112 students responded to the survey. The data were mainly analysed with qualitative methods. In the eTaitava web-based user interface, the teacher constructs questions to map the students’ learning process, and sets them to be sent on a daily basis. According to the findings, four-fifths of the students responded to the questions almost daily. They thought the software was easy to use and answering the questions took about 5 minutes a day. Based on the students’ and teachers’ experiences, the use of the electronic assessment and feedback tool supported supervision of clinical training. It supported the students’ target-oriented learning, supervised the students’ daily work, and made it visible for the teachers. Responding to the software questions inspired the students’ cognitive learning, and based on the responses, the teachers noticed which students needed more support and could consequently allocate them more supervision time. Responding also supported the students’ continuous self-evaluation, and considering the responses structured the students’ and teachers’ final assessment discussion. By means of the electronic assessment and feedback tool, it is possible to promote learning during clinical training by challenging students to reflect on their learning experiences. -

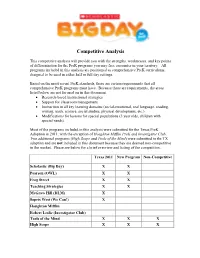

Competitive Analysis

Competitive Analysis This competitive analysis will provide you with the strengths, weaknesses, and key points of differentiation for the PreK programs you may face encounter in your territory. All programs included in this analysis are positioned as comprehensive PreK curriculums, designed to be used in either half or full day settings. Based on the most recent PreK standards, there are certain requirements that all comprehensive PreK programs must have. Because these are requirements, the areas listed below are not focused on in this document. • Research-based instructional strategies • Support for classroom management • Instruction in all key learning domains (social-emotional, oral language, reading, writing, math, science, social studies, physical development, etc.) • Modifications for lessons for special populations (3 year olds, children with special needs). Most of the programs included in this analysis were submitted for the Texas PreK Adoption in 2011, with the exception of Houghton Mifflin PreK and Investigator Club. Two additional programs (High Scope and Tools of the Mind) were submitted in the TX adoption and are not included in this document because they are deemed non-competitive in the market. Please see below for a brief overview and listing of the competition. Texas 2011 New Program Non-Competitive Scholastic (Big Day) X X Pearson (OWL) X X Frog Street X X Teaching Strategies X X McGraw Hill (DLM) X Sopris West (We Can!) X Houghton Mifflin Robert Leslie (Investigator Club) Tools of the Mind X X X High Scope X X X Competitive -

Electronic Management of Assessment (EMA): a Landscape Review

Electronic Management of Assessment (EMA): a landscape review August 2014 Author Dr Gill Ferrell “Electronic Management of Assessment (EMA): a landscape review” Author Dr Gill Ferrell © Jisc Published under the CC BY 2.0 licence creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ Contents Introduction 4 Information sources 6 General overview of landscape 8 Take up of EMA within institutions 9 Technologies in use 12 Processes 14 Pain points 16 A Life-cycle view 19 1. Specifying 21 2. Setting 23 3. Supporting 24 4. Submitting 25 5. Marking and production of feedback 27 Models of marking 28 Anonymous marking 29 Individual marking practice 29 6. Recording grades 31 7. Returning marks and feedback 33 8. Reflecting 34 Working with suppliers 36 Recommendations and next steps 37 References 39 Appendix 1: Summary of lifecycle issues 40 Appendix 2: Accessible and inclusive EMA 42 Appendix 3: List of institutions participating in Think Tank 44 Acknowledgements 44 Electronic Management of Assessment (EMA): a landscape review 4 Introduction Introduction The term electronic management of assessment (EMA1) is increasingly being used to describe the way that technology can be used to support the management of the whole assessment and feedback lifecycle, including the electronic submission of assignments, marking, feedback and the return of marks and feedback to students. We look in more detail at the components of this life cycle with their time management, being able to submit work later in this report: suffice it to say here that the effective in a way that suits them and receiving feedback that management of assessment and feedback is central to helps their longitudinal development. -

Book: Observation and Assessment in Early Childhood Education

OBSERVATION AND ASSESSMENT IN EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION Gina Peterson and Emily Elam College of the Canyons Book: Observation and Assessment in Early Childhood Education (Peterson and Elam) This text is disseminated via the Open Education Resource (OER) LibreTexts Project (https://LibreTexts.org) and like the hundreds of other texts available within this powerful platform, it freely available for reading, printing and "consuming." Most, but not all, pages in the library have licenses that may allow individuals to make changes, save, and print this book. Carefully consult the applicable license(s) before pursuing such effects. Instructors can adopt existing LibreTexts texts or Remix them to quickly build course-specific resources to meet the needs of their students. Unlike traditional textbooks, LibreTexts’ web based origins allow powerful integration of advanced features and new technologies to support learning. The LibreTexts mission is to unite students, faculty and scholars in a cooperative effort to develop an easy-to-use online platform for the construction, customization, and dissemination of OER content to reduce the burdens of unreasonable textbook costs to our students and society. The LibreTexts project is a multi-institutional collaborative venture to develop the next generation of open-access texts to improve postsecondary education at all levels of higher learning by developing an Open Access Resource environment. The project currently consists of 13 independently operating and interconnected libraries that are constantly being optimized by students, faculty, and outside experts to supplant conventional paper-based books. These free textbook alternatives are organized within a central environment that is both vertically (from advance to basic level) and horizontally (across different fields) integrated. -

E-Assessment: Guide to Effective Practice (Full Version)

E-Assessment Cover AW 13/8/07 14:25 Page 2 e-Assessment Guide to effective practice H04435 e-assement IFC 13/8/07 16:32 Page IFC The regulators of external qualifications wish to make their publications widely accessible. Please contact us if you have any specific accessibility requirements. Acknowledgements The Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA), the Department for Children, Education, Lifelong Learning and Skills (DCELLS), the Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessments (CCEA) and the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) wish to thank a number of organisations for their contributions and support in the development of this guide: Advice NI; The CADCentre UK Ltd; Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply; CITB Construction Skills; EAGIT Ltd; Hyfforddiant Mon Training; Lambeth College; Northern Ireland Civil Service Centre for Applied Learning; Northumberland County Council Adult Learning Service; North West Institute of Further and Higher Education; Open College Network London Region; Stockton Riverside College; and Ystrad Mynach College. Our thanks go also to Paul Ellis and Kate Shoesmith from the Federation of Awarding Bodies; to Angela Joyce and Liz Hall from Lifelong Learning UK; and to Sally-Anne Saull from the Association of Colleges for their support in the process of consultation on various versions of the guide. The qualifications regulators would also like to express our thanks to Patrick Coates, Martyn Roads and Paula Taylor, consultants to the project, who did so much of the practical work in producing the guide. First published in 2007 © Crown copyright 2007 © Northern Ireland Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment 2007 © Qualifications and Curriculum Authority 2007 © Scottish Qualifications Authority 2007 ISBN 1-85838-979-2 Reproduction, storage or translation, in any form or by any means, of this publication is prohibited without prior written permission of the publisher, unless within the terms of the Copyright Licensing Agency. -

Principles of Effective E-Assessment: a Proposed Framework

Journal of International Business Education 11: 65-92. © 2016 NeilsonJournals Publishing. Principles of Effective E-Assessment: A Proposed Framework Rouxelle de Villiers, Joanna Scott-Kennel, and Roy Larke Waikato Management School, University of Waikato, New Zealand Abstract. Simultaneous educational transitions including the rapid expansion in blended andragogy, advances in technology and digital teaching aids, and the increased availability and uptake of online distance learning are driving a need for new approaches to assessment for e- learning and business competency teaching. This study aligns previous research relating to traditional tertiary-level assessment with e-learning and blended learning teaching strategies and practices. This reformulation, combined with insights from e-learning educators, facilitators and students, results in a new framework consisting of seven principles of best practice in e-assessment strategies. A key insight highlighted by this study is that modern andragogy, aided by technology, allows students to co-create knowledge and make sense of complex concepts via the student-peer- facilitator tripartite. This study presents each of the seven principles, along with examples of successful assessment strategies implemented in international business and marketing classes at tertiary level. Keywords: assessment; blended learning; co-creation of knowledge; e-assessments; e-learning; experiential learning; flipped classes; online assessments; business education, social media. Assessment: from the Latin root assidere, to sit beside another. 1. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to provide insight into the andragogy of e-assessment and to investigate key principles which will guide international business educators’ strategies and practices involving e-assessment tools. The paper proposes that seven principles, namely affordance, alignment, articulation, accountability, accreditation, adaptation and authenticity, are fundamental to all types of e-assessments, irrespective of context, content or stakeholders. -

Reliability and Validity of International Large- Scale Assessment Understanding IEA’S Comparative Studies of Student Achievement IEA Research for Education

IEA Research for Education A Series of In-depth Analyses Based on Data of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) Hans Wagemaker Editor Reliability and Validity of International Large- Scale Assessment Understanding IEA’s Comparative Studies of Student Achievement IEA Research for Education A Series of In-depth Analyses Based on Data of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) Volume 10 Series Editors Seamus Hegarty, Chair of IEA Publications and Editorial Committee, University of Warwick, UK Leslie Rutkowski, Indiana University, USA Editorial Board John Ainley, Australian Council for Educational Research, Australia Sarah Howie, Stellenbosch University, South Africa Eckhard Klieme, German Institute for International Educational Research (DIPF), Germany Rainer Lehmann, Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany Fou-Lai Lin, National Taiwan Normal University, Chinese Taipei Marlaine Lockheed, Princeton University, USA Sarah Maughan, AlphaPlus Consultancy, UK Maia Miminoshvili, President, Education Policy and Research Association (EPRA), Georgia Carina Omoeva, FHI 360, USA Elena Papanastasiou, University of Nicosia, Cyprus Valena White Plisko, Independent Consultant, USA David Rutkowski, Indiana University, USA Franck Salles, Ministère de l'Education nationale, France Andres Sandoval Hernandez, University of Bath, UK Jouni Välijärvi, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Hans Wagemaker, Senior Advisor to IEA, New Zealand The International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) is an independent nongovernmental nonprofit cooperative of national research institutions and governmental research agencies that originated in Hamburg, Germany in 1958. For over 60 years, IEA has developed and conducted high-quality, large-scale comparative studies in education to support countries’ efforts to engage in national strategies for educational monitoring and improvement.