Master Gardener PUBLISHED by UNIVERSITY of MISSOURI EXTENSION Extension.Missouri.Edu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Totalex® Registrant Name Ready-To-Use

19-SEP-2006 18-DEC-2007 Notification - Change in Registrant Address 14-FEB-2008 Notification - Change in TotalEx® Registrant Name Ready-To-Use Brush, Grass & Weed Killer Home Gardener® Brush, Grass & Broadleaf Weed Control Liquid Controls Entire Plant, Burns Off Leaves And Stem And Kills Roots NON-SELECTIVE HERBICIDE NO RESIDUAL ACTIVITY IN SOIL READ THE LABEL BEFORE USING KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN DOMESTIC REG. NO. 28470 P.C.P. ACT GUARANTEE: glyphosate 7 g/L (present as isopropylamine salt) Contains 1,2-benzisothiazolin-3-one at 0.039% as a preservative Net Contents: 1 L (2 L) (4L) Teragro Inc. Virterra Products Corporation RR#7, Site 11 - Box 16 P.O. Box 137 Calgary, Alberta Chestermere AB T1X 1K8 T2P 2G7 www.virterraproducts.com ®TotalEx is a registered trademark of Virterra Products Corporation TotalEx® Ready-To-Use Brush, Grass & Weed Killer Home Gardener In case of a medical emergency, call toll free day or night 1-866-303-6950 GENERAL PRODUCT INFORMATION TotalEx® Ready-to-Use Brush, Grass & Weed Killer Home Gardener is a non-selective herbicide. It controls most annual and perennial grasses, including lawn grasses, broadleaf weeds such as chickweed, ragweed, knotweed, poison ivy, Canada thistle, milkweed, bindweed and most brush such as poplar, alder, maple and raspberry. (i.e. virtually anything that is green and growing). It is absorbed by the leaves and moves throughout the stem and roots to control the entire plant. Mature perennial weeds should be treated after seed heads, flowers or fruit appear. All plants are most easily controlled in the young, actively growing, seedling stage. -

Approved References for Pest Management Recommendations

Approved References for Pest Management Recommendations Non-Chemical Management Options Non-chemical management options include cultural, physical, mechanical, and biological strategies. These strategies include, but are not limited to traps, physical barriers, beneficial insects, nematodes, and handpicking. WSU Master Gardener Volunteers may recommend non-chemical management options from the following resources: . Gardening in Washington State (all publications) . WSU Extension Bulletins (EB) (latest versions) . WSU Extension Memos (EM) (latest versions) . PNW Insect Management Handbook (Home Landscape section only) (WSU-MISC0047) . PNW Plant Disease Management Handbook (Listings with “H” next to them indicate homeowner products) (WSU-MISC0048) . PNW Weed Management Handbook (Lawn Section only) (WSU-MISC0049) . WSU Pest Leaflet Series (PLS) . Pacific NW Landscape Integrated Pest Management Manual (WSU-MISC0201) . WSU Hortsense Fact Sheets or web site . Orchard Pest Management: A Resource Guide for the Pacific Northwest . (Good Fruit Grower Publication, ISBN 0-9630659-3-9) . Pests of Landscape Trees and Shrubs: An Integrated Pest Management Guide (University of California, Publication #3359, ISBN 1-879906-18-X) . Pests of Garden and Small Farm: A Grower’s Guide to Using Less Pesticide . (University of California, publication #3332, ISBN 0-931876-89-3) . Common-Sense Pest Control: Least-Toxic Solutions for Your Home, Garden, Pets and Community (Taunton Press, ISBN 978-0942391633) . Christmas Tree Diseases, Insects and Disorders in the Pacific Northwest: Identification and Management (WSU MISC0186) . Garden Insects of North America: The Ultimate Guide to Backyard Bugs . (Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-09560-4) . Ortho Home Gardener’s Problem Solver . (Ortho Books, San Ramon, CA) . Rodale’s Garden Problem Solver: Vegetables, Fruits and Herbs . -

Block Style Layout in Raised Bed Vegetable Gardens

GMG GardenNotes #713 Block Style Layout in Raised Bed Vegetable Gardens Outline: Block style garden layout, page 1 Suggested spacing, page 2 Raised bed gardens, page 4 Construction of a raised bed garden, page 5 Gardening with raised beds, page 7 Block Style Garden Layout Block style garden layout (also called close-row or wide-row plantings) increase yields five fold compared to the traditional row-style garden layout, and 15-fold for the smaller kitchen garden vegetables. The compact design reduces weeding and is ideal for raised bed gardening. The basic technique used in close-row, block planting is to eliminate unnecessary walkways by planting vegetables in rectangular-shaped beds or blocks instead of long single rows. For example, plant a block of carrots next to a block of beets, followed with a block of lettuce and so forth down the bed area. Plant crops with an equal-distance space between neighboring plants in both directions. For example, space a carrot patch on 3-inch by 3-inch centers. It may be easier to visualize this plant layout as running rows spaced 3 inches apart across the bed, and thinning the carrots within the row to 3 inches. A 24-foot long “traditional” row of carrots will fit into a 3 foot by 2-foot bed. [Figure 1] Design the planting beds to be 3 to 4 feet wide and any desired length. This width makes it easy to reach into the growing bed from Figure 1. Carrots planted on walkways for planting, weeding and harvesting. 3-inch centers Limiting foot traffic to the established walkways between planting beds reduces soil compaction. -

HO-105: Landscape Design: Kentucky Master Gardener Manual Chapter 17

University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, HO-105 Food and Environment Cooperative Extension Service Landscape Design Kentucky Master Gardener Manual Chapter 17 By Jan McNeilan, retired Extension consumer horticulturist, and Ann Marie VanDerZanden, former Extension master gardener state coor- dinator, both of Oregon State University. Adapted for use in Kentucky by Rick Durham, consumer horticulture extension specialist and master gardener state coordinator. andscape designs differ depending on how the landscape In this chapter: will be used. Although the principles are the same, a home- owner who wants an aesthetically pleasing, low-maintenance Planning ................................................................242 Llandscape will create a design very different than that of an avid Parts of a Landscape.........................................244 gardener whose main purpose in life is to spend time in the garden. This chapter is not meant to define the art of landscape design Elements and Principles of Design .............246 but rather to help you take a realistic approach to landscape plan- Plant Selection ....................................................247 ning. Your end design should meet your needs and incorporate Drawing a Landscape Plan .............................251 principles of sustainability into an evolving landscape. Kentucky gardeners are fortunate to be able to use a wide variety Renovating an Established Landscape ......254 of plant materials to create landscapes that meet their needs. This Evaluating Landscape Sustainability .........255 available diverse plant material can be used to create outdoor rooms with canopies of trees; walls of shrubs and vines; and carpets of For More Information .......................................256 groundcovers, perennials, and annuals to provide color and interest. Landscape Design Planning Before beginning, consider what type of landscape will suit your Questionnaire .....................................................257 needs. -

Evaluation of the Osmotic Adjustment Response Within the Genus Beta

July 2008 - Dec. 2008 Osmotic Adjustment Response 119 Evaluation of the Osmotic Adjustment Response within the Genus Beta Manuela Bagatta, Daniela Pacifico, and Giuseppe Mandolino C.R.A. – Centro di Ricerca per le Colture Industriali Via di Corticella 133 – 40128 Bologna (Italy) Corresponding author: Giuseppe Mandolino ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Beta genus includes both industrial and horticultural spe- cies, and wild species and subspecies, which are possible reservoirs of agronomically important characters. Among the traits for which Beta has been recently studied, drought tolerance or avoidance is one of the most important. In this work, relative water content and the osmotic potential in well-watered and stressed conditions of three beet types, one B. vulgaris subspecies and one species other than B. vulgaris, all belonging to the Beta genus, were analysed. In addition, relative water content, succulence index and osmotic potential were measured during a three-week water deprivation period, and the osmotic adjustment was estimated for each Beta accession. The results showed that succulence was higher for B. vulgaris ssp. maritima. It was also shown that all Beta accessions were capable of adjust- ing osmotically, but that the B. vulgaris maritima accession examined had a higher osmotic adjustment value compared to the accessions belonging to cultivated Beta types, and that the accession of the wild species Beta webbiana had a comparatively limited capacity to adjust osmotically. Additional key words: Sugarbeet, sea beet, germplasm, drought, osmotic adjustment rought is one of the greatest limitations for agriculture and crop expansion (Boyer, 1982). Sugarbeet (Beta vulgaris ssp. vulgaris) is aD deep-rooting crop, more adapted to withstand water shortage or nutri- tional deprivation than many other crops (Doorenbos and Kassam, 1979; Biancardi et al., 1998); however, drought stress is becoming a major 120 Journal of Sugar Beet Research Vol. -

PRUNING TIPS by Sue Mcdavid UCCE El Dorado County Master Gardener

PRUNING TIPS By Sue McDavid UCCE El Dorado County Master Gardener Many may think it is not the time of year to be thinking of pruning, but summer pruning has many advantages over dormant-season pruning. If a gardener wishes to keep trees from growing too large, pruning in the summertime will help achieve that goal by devigorating the tree . the loss of leaves during the pruning process leads to less photosynthesis and, thus, less growth. The best time to summer-prune is from late May (ideally, it should begin after the new vegetative growth has reached three to four inches in length) to late July or early August, so right now is the best time to do it. For most purposes, summer pruning should be limited to removing the upright and vigorous current season's growth; with only thinning cuts being used (thinning cuts remove an entire shoot back to a side shoot). Thinning cuts do not invigorate a tree or shrub in comparison to some of the other types of pruning cuts. A good point to remember is that pruning in late winter or early spring (before bud break) actually invigorates a shrub or tree because it causes new tissue to form rapidly. Therefore, if the goal is a smaller tree or shrub, late winter or early spring are not the times to prune. Another point to remember about pruning is that it should be delayed on any spring-blooming shrubs or trees until immediately after flowering; otherwise, you may end up with no bloom at all. That goes for summer-blooming shrubs and trees as well – these should be pruned immediately following flowering. -

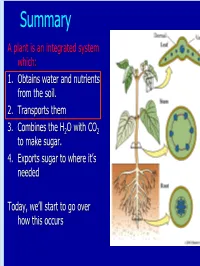

Summary a Plant Is an Integrated System Which: 1

Summary A plant is an integrated system which: 1. Obtains water and nutrients from the soil. 2. Transports them 3. Combines the H2O with CO2 to make sugar. 4. Exports sugar to where it’s needed Today, we’ll start to go over how this occurs Transport in Plants – Outline I.I. PlantPlant waterwater needsneeds II.II. TransportTransport ofof waterwater andand mineralsminerals A.A. FromFrom SoilSoil intointo RootsRoots B.B. FromFrom RootsRoots toto leavesleaves C.C. StomataStomata andand transpirationtranspiration WhyWhy dodo plantsplants needneed soso muchmuch water?water? TheThe importanceimportance ofof waterwater potential,potential, pressure,pressure, solutessolutes andand osmosisosmosis inin movingmoving water…water… Transport in Plants 1.1. AnimalsAnimals havehave circulatorycirculatory systems.systems. 2.2. VascularVascular plantsplants havehave oneone wayway systems.systems. Transport in Plants •• OneOne wayway systems:systems: plantsplants needneed aa lotlot moremore waterwater thanthan samesame sizedsized animals.animals. •• AA sunflowersunflower plantplant “drinks”“drinks” andand “perspires”“perspires” 1717 timestimes asas muchmuch asas aa human,human, perper unitunit ofof mass.mass. Transport of water and minerals in Plants WaterWater isis goodgood forfor plants:plants: 1.1. UsedUsed withwith CO2CO2 inin photosynthesisphotosynthesis toto makemake “food”.“food”. 2.2. TheThe “blood”“blood” ofof plantsplants –– circulationcirculation (used(used toto movemove stuffstuff around).around). 3.3. EvaporativeEvaporative coolingcooling. -

Home Vegetable Gardening in Washington

Home Vegetable Gardening in Washington WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION • EM057E This manual is part of the WSU Extension Home Garden Series. Home Vegetable Gardening in Washington Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................1 Vegetable Garden Considerations ..................................................................................................1 Site-Specific Growing Conditions .............................................................................................1 Crop Selection .........................................................................................................................3 Tools and Equipment .....................................................................................................................6 Vegetable Planting .........................................................................................................................7 Seeds .......................................................................................................................................7 Transplants .............................................................................................................................10 Planting Arrangements ................................................................................................................14 Row Planting ..........................................................................................................................14 -

An Introduction to Being a Master Gardener Volunteer

EM 8749 Revised September 2014 An MASTER introduction to being a GARDENERVOLUNTEER 3 An introduction to being a Master Gardener volunteer Contents Oregon Master Gardeners are part of the OSU Extension Service 36 A brief history of our national Extension system 37 History of the Master Gardener Program 38 The Oregon Master Gardener Program 38 Why become a Master Gardener? 39 Who uses the services of the Master Gardener Program? 10 Master Gardener Program policies and guidelines 11 Master Gardener trainee classes 14 Final examination 14 Volunteer commitment and projects 15 Certification 16 Can you be paid for volunteer service? 16 Guarding against volunteer burnout 17 Providing gardening recommendations for the general public 18 Concluding thoughts 20 The most important thing to know is that you don’t have to ‘know’ everything. You “just need to know where and how to find good information. Also, it is helpful to know at the beginning that the whole Master Gardener experience is one of continuous learning. No matter how hard everyone tries, you can’t get it all at the beginning but can absorb it as the years go by. — Response from a current Master Gardener, to the question “What” do you wish you had known when you started your Master Gardener training?” Cover photo: Master Gardeners (l-r) Nakisha Nathan, Brynna McCarter, and John Jordan. Photo by Gillian Carson. Used with permission. 4 An introduction to being a Master Gardener volunteer An MASTER introduction to being a GARDENER VOLUNTEER Photo by Ryan Creason, © Oregon State University State © Oregon Ryan by Creason, Photo Figure 1. -

Become a Texas Master Gardener

BECOME A TEXAS MASTER GARDENER Who are Texas Master Gardeners? Master Gardeners are members of the local community who take an active interest in their lawns, trees, shrubs, flowers and gardens. They are enthusiastic, willing to learn and to help others, and able to communicate with diverse groups of people. What really sets Master Gardeners apart from other home gardeners is their special training in horticulture. In exchange for their training, persons who become Master Gardeners contribute time as volunteers, working through their cooperative Extension office to provide horticultural-related information to their communities. Is the Master Gardener Program for Me? To help you decide if you should apply to be a Master Gardener, if you answer yes to these questions, the Master Gardener program could be for you. * Do I want to learn more about the culture and maintenance of many types of plants? * Am I eager to participate in a practical and intense training program? * Do I look forward to sharing my knowledge with people in my community? * Do I have enough time to attend training and to complete the volunteer service? Training If accepted into the Master Gardener program in your county, you will attend a Master Gardener training course. Classes are taught by Texas AgriLife Extension Service specialists, staff, and local experts. The program offers a minimum of 50 hours of instruction that covers topics including lawn care, ornamental trees and shrubs, insect, disease, and weed management; soils and plant nutrition, vegetable gardening; home fruit production; garden flowers; and water conservation. Volunteer Commitment In exchange for training, participants are asked to volunteer time to their County Extension program. -

The Climate Action Plan for Nature (CAPN)

CHICAGO COMMUNITY CLIMATE ACTION TOOLKIT CHICAGO WILDERNESS CLIMATE ACTION PLAN FOR NATURE (CAPN) COMMUNITY ACTION STRATEGIES A CLIMATE ACTION TOOL THAT ADDRESSES THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Find this and other climate action tools at Environment Culture and Conservation climatechicago.fieldmuseum.org A Division of Science COMMUNITY ACTION STRATEGIES Climate change is affecting both people and nature in These community action strategies are designed to assist the Chicago Region. Chicago Wilderness, a regional individuals and communities to: alliance of more than 250 organizations, created a plan called the Chicago Wilderness Climate Action Plan for 1. mitigate , or lessen the future impacts, of climate Nature (CAPN)1 to address the impacts of climate change change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, on local nature and identify strategies to help natural areas respond and adapt to changes in our climate. 2. help native plants and animals adapt to climate This document outlines how every Chicagoan can help change, or implement the goals of the Chicago Wilderness CAPN in their own community through the following ways: 3. both. For example, converting underutilized areas of lawn grass into native gardens is an action that can help CLIMATE-FRIENDLY GARDENS AND LAWNS 1 human and natural communities both mitigate and adapt to climate change. Since native plants do not require regular mowing like lawn grass, lawn mower greenhouse WATER CONSERVATION 2 gas emissions are eliminated, thereby mitigating these emissions and reducing climate change impacts. Native plants also provide habitat for birds, butterflies, and other MONITORING 3 insects, creating islands of habitat in urban areas that can be beneficial as species adapt to a changing climate. -

Transport of Water and Solutes in Plants

Transport of Water and Solutes in Plants Water and Solute Potential Water potential is the measure of potential energy in water and drives the movement of water through plants. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Describe the water and solute potential in plants Key Points Plants use water potential to transport water to the leaves so that photosynthesis can take place. Water potential is a measure of the potential energy in water as well as the difference between the potential in a given water sample and pure water. Water potential is represented by the equation Ψsystem = Ψtotal = Ψs + Ψp + Ψg + Ψm. Water always moves from the system with a higher water potential to the system with a lower water potential. Solute potential (Ψs) decreases with increasing solute concentration; a decrease in Ψs causes a decrease in the total water potential. The internal water potential of a plant cell is more negative than pure water; this causes water to move from the soil into plant roots via osmosis.. Key Terms solute potential: (osmotic potential) pressure which needs to be applied to a solution to prevent the inward flow of water across a semipermeable membrane transpiration: the loss of water by evaporation in terrestrial plants, especially through the stomata; accompanied by a corresponding uptake from the roots water potential: the potential energy of water per unit volume; designated by ψ Water Potential Plants are phenomenal hydraulic engineers. Using only the basic laws of physics and the simple manipulation of potential energy, plants can move water to the top of a 116-meter-tall tree. Plants can also use hydraulics to generate enough force to split rocks and buckle sidewalks.