Douglas-Fir and White Fir Descriptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tree Species Distribution Maps for Central Oregon

APPENDIX 7: TREE SPECIES DISTRIBUTION MAPS FOR CENTRAL OREGON A7-150 Appendix 7: Tree Species Distribution Maps Table A7-5. List of distribution maps for tree species of central Oregon. The species distribution maps are prefaced by four maps (pages A7-151 through A7-154) showing all locations surveyed in each of the four major data sources Map Page Forest Inventory and Analysis plot locations A7-151 Ecology core Dataset plot locations A7-152 Current Vegetation Survey plot locations A7-153 Burke Museum Herbarium and Oregon Flora Project sample locations A7-154 Scientific name Common name Symbol Abies amabilis Pacific silver fir ABAM A7-155 Abies grandis - Abies concolor Grand fir - white fir complex ABGR-ABCO A7-156 Abies lasiocarpa Subalpine fir ABLA A7-157 Abies procera - A. x shastensis Noble fir - Shasta red fir complex ABPR-ABSH A7-158 [magnifica x procera] Acer glabrum var. douglasii Douglas maple ACGLD4 A7-159 Alnus rubra Red alder ALRU2 A7-160 Calocedrus decurrens Incense-cedar CADE27 A7-161 Chrysolepis chrysophylla Golden chinquapin CHCH7 A7-162 Frangula purshiana Cascara FRPU7 A7-163 Juniperus occidentalis Western juniper JUOC A7-164 Larix occidentalis Western larch LAOC A7-165 Picea engelmannii Engelmann spruce PIEN A7-166 Pinus albicaulis Whitebark pine PIAL A7-167 Pinus contorta var. murrayana Sierra lodgepole pine PICOM A7-168 Pinus lambertiana Sugar pine PILA A7-169 Pinus monticola Western white pine PIMO3 A7-170 Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa pine PIPO A7-171 Populus balsamifera ssp. trichocarpa Black cottonwood POBAT A7-172 -

Psme 46 Douglas-Fir-Incense

PSME 46 DOUGLAS-FIR-INCENSE-CEDAR/PIPER'S OREGONGRAPE Pseudotsuga menziesii-Calocedrus decurrens/Berberis piperiana PSME-CADE27/BEPI2 (N=18; FS=18) Distribution. This Association occurs on the Applegate, Ashland, and Prospect Ranger Districts, Rogue River National Forest, and the Tiller and North Umpqua Ranger Districts, Umpqua National Forest. It may also occur on the Butte Falls Ranger District, Rogue River National Forest and adjacent Bureau of Land Management lands. Distinguishing Characteristics. This is a drier, cooler Douglas-fir association. White fir is frequently present, but with relatively low covers. Piper's Oregongrape and poison oak, dry site indicators, are also frequently present. Soils. Parent material is mostly schist, welded tuff, and basalt, with some andesite, diorite, and amphibolite. Average surface rock cover is 8 percent, with 8 percent gravel. Soils are generally deep, but may be moderately deep, with an average depth of greater than 40 inches. PSME 47 Environment. Elevation averages 3000 feet. Aspects vary. Slope averages 35 percent and ranges between 12 and 62 percent. Slope position ranges from the upper one-third of the slope down to the lower one-third of the slope. This Association may also occur on benches and narrow flats. Vegetation Composition and Structure. Total species richness is high for the Series, averaging 44 percent. The overstory is dominated by Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine, with sugar pine and incense-cedar common associates. Douglas-fir dominates the understory. Incense-cedar, white fir, and Pacific madrone frequently occur, generally with covers greater than 5 percent. Sugar pine is common. Frequently occurring shrubs include Piper's Oregongrape, baldhip rose, poison oak, creeping snowberry, and Pacific blackberry. -

Susceptibility of Larch, Hemlock, Sitka Spruce, and Douglas-Fir to Phytophthora Ramorum1

Proceedings of the Sudden Oak Death Fifth Science Symposium Susceptibility of Larch, Hemlock, Sitka Spruce, and 1 Douglas-fir to Phytophthora ramorum Gary Chastagner,2 Kathy Riley,2 and Marianne Elliott2 Introduction The recent determination that Phytophthora ramorum is causing bleeding stem cankers on Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi (Lam.) Carrière) in the United Kingdom (Forestry Commission 2012, Webber et al. 2010), and that inoculum from this host appears to have resulted in disease and canker development on other conifers, including western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla (Raf.) Sarg.), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco), grand fir (Abies grandis (Douglas ex D. Don) Lindl.), and Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carrière), potentially has profound implications for the timber industry and forests in the United States Pacific Northwest (PNW). A clearer understanding of the susceptibility of these conifers to P. ramorum is needed to assess the risk of this occurring in the PNW. Methods An experiment was conducted to examine the susceptibility of new growth on European (L. decidua Mill.), Japanese, eastern (L. laricina (Du Roi) K. Koch), and western larch (L. occidentalis Nutt.); western and eastern hemlock (T. canadensis (L.) Carrière); Sitka spruce; and a coastal seed source of Douglas-fir to three genotypes (NA1, NA2, and EU1) of P. ramorum in 2011. In 2012, a similar experiment was conducted using only the four larch species. Container-grown seedlings or saplings were used in all experiments. Five trees or branches of each species were inoculated with a single isolate of the three genotypes by spraying the foliage with a suspension of zoospores (105/ml). -

DOUGLAS's Datasheet

DOUGLAS Page 1of 4 Family: PINACEAE (gymnosperm) Scientific name(s): Pseudotsuga menziesii Commercial restriction: no commercial restriction Note: Coming from North West of America, DOUGLAS FIR is often used for reaforestation in France and in Europe. Properties of european planted trees (young and with a rapid growth) which are mentionned in this sheet are different from those of the "Oregon pine" (old and with a slow growth) coming from its original growing area. WOOD DESCRIPTION LOG DESCRIPTION Color: pinkish brown Diameter: from 50 to 80 cm Sapwood: clearly demarcated Thickness of sapwood: from 5 to 10 cm Texture: medium Floats: pointless Grain: straight Log durability: low (must be treated) Interlocked grain: absent Note: Heartwood is pinkish brown with veins, the large sapwood is yellowish. Wood may show some resin pockets, sometimes of a great dimension. PHYSICAL PROPERTIES MECHANICAL AND ACOUSTIC PROPERTIES Physical and mechanical properties are based on mature heartwood specimens. These properties can vary greatly depending on origin and growth conditions. Mean Std dev. Mean Std dev. Specific gravity *: 0,54 0,04 Crushing strength *: 50 MPa 6 MPa Monnin hardness *: 3,2 0,8 Static bending strength *: 91 MPa 6 MPa Coeff. of volumetric shrinkage: 0,46 % 0,02 % Modulus of elasticity *: 16800 MPa 1550 MPa Total tangential shrinkage (TS): 6,9 % 1,2 % Total radial shrinkage (RS): 4,7 % 0,4 % (*: at 12% moisture content, with 1 MPa = 1 N/mm²) TS/RS ratio: 1,5 Fiber saturation point: 27 % Musical quality factor: 110,1 measured at 2971 Hz Stability: moderately stable NATURAL DURABILITY AND TREATABILITY Fungi and termite resistance refers to end-uses under temperate climate. -

Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth Northwest Forests'

AMER. ZOOL., 33:578-587 (1993) Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth mon et al., 1990; Hz Northwest Forests complex litter layer 1973; Lattin, 1990; JOHN D. LATTIN and other features Systematic Entomology Laboratory, Department of Entomology, Oregon State University, tural diversity of th Corvallis, Oregon 97331-2907 is reflected by the 14 found there (Lawtt SYNOPSIS. Old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest extend along the 1990; Parsons et a. e coastal region from southern Alaska to northern California and are com- While these old posed largely of conifer rather than hardwood tree species. Many of these ity over time and trees achieve great age (500-1,000 yr). Natural succession that follows product of sever: forest stand destruction normally takes over 100 years to reach the young through successioi mature forest stage. This succession may continue on into old-growth for (Lattin, 1990). Fire centuries. The changing structural complexity of the forest over time, and diseases, are combined with the many different plant species that characterize succes- bances. The prolot sion, results in an array of arthropod habitats. It is estimated that 6,000 a continually char arthropod species may be found in such forests—over 3,400 different ments and habitat species are known from a single 6,400 ha site in Oregon. Our knowledge (Southwood, 1977 of these species is still rudimentary and much additional work is needed Lawton, 1983). throughout this vast region. Many of these species play critical roles in arthropods have lx the dynamics of forest ecosystems. They are important in nutrient cycling, old-growth site, tt as herbivores, as natural predators and parasites of other arthropod spe- mental Forest (HJ cies. -

Conifer Reproductive Biology Claire G

Conifer Reproductive Biology Claire G. Williams Conifer Reproductive Biology Claire G. Williams USA ISBN: 978-1-4020-9601-3 e-ISBN: 978-1-4020-9602-0 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4020-9602-0 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2009927085 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Cover Image: Snow and pendant cones on spruce tree (reproduced with permission of Photos.com). Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Foreword When it comes to reproduction, gymnosperms are deeply weird. Cycads and coni- fers have drawn out reproduction: at least 13 genera take over a year from pollina- tion to fertilization. Since they don’t apparently have any selection mechanism by which to discriminate among pollen tubes prior to fertilization, it is natural to won- der why such a delay in reproduction is necessary. Claire Williams’ book celebrates such oddities of conifer reproduction. She has written a book that turns the context of many of these reproductive quirks into deeper questions concerning evolution. The origins of some of these questions can be traced back Wilhelm Hofmeister’s 1851 book, which detailed the revolutionary idea of alternation of generations. -

Western Larch, Which Is the Largest of the American Larches, Occurs Throughout the Forests of West- Ern Montana, Northern Idaho, and East- Ern Washington and Oregon

Forest An American Wood Service Western United States Department of Agriculture Larch FS-243 The spectacular western larch, which is the largest of the American larches, occurs throughout the forests of west- ern Montana, northern Idaho, and east- ern Washington and Oregon. Western larch wood ranks among the strongest of the softwoods. It is especially suited for construction purposes and is exten- sively used in the manufacture of lumber and plywood. The species has also been used for poles. Water-soluble gums, readily extracted from the wood chips, are used in the printing and pharmaceutical industries. F–522053 An American Wood Western Larch (Lark occidentalis Nutt.) David P. Lowery1 Distribution Western larch grows in the upper Co- lumbia River Basin of southeastern British Columbia, northeastern Wash- ington, northwest Montana, and north- ern and west-central Idaho. It also grows on the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and north- central Oregon and in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains of southeast Wash- ington and northeast Oregon (fig. 1). Western larch grows best in the cool climates of mountain slopes and valleys on deep porous soils that may be grav- elly, sandy, or loamy in texture. The largest trees grow in western Montana and northern Idaho. Western larch characteristically occu- pies northerly exposures, valley bot- toms, benches, and rolling topography. It occurs at elevations of from 2,000 to 5,500 feet in the northern part of its range and up to 7,000 feet in the south- ern part of its range. The species some- times grows in nearly pure stands, but is most often found in association with other northern Rocky Mountain con- ifers. -

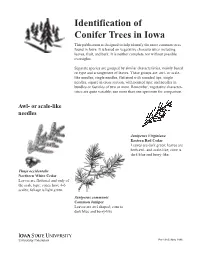

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

7. PSEUDOLARIX Gordon, Pinetum 292. 1858, Nom. Cons. 金钱松属 Jin Qian Song Shu Chrysolarix H

Flora of China 4: 41–42. 1999. 7. PSEUDOLARIX Gordon, Pinetum 292. 1858, nom. cons. 金钱松属 jin qian song shu Chrysolarix H. E. Moore; Laricopsis Kent. Trees deciduous; trunk monopodial, straight, terete; branches irregularly whorled; branchlets strongly dimorphic: long branchlets with leaves spirally arranged and radially spreading; short branchlets with leaves radially arranged in false whorls of 10–30 (often spirally spread like a discoid star). Leaves green, turning golden yellow before falling in autumn, narrowly oblanceolate-linear, flattened, 1.5–4 mm wide, flexible, stomatal lines abaxial, in 2 bands, separated by midvein, vascular bundle 1, resin canals 2 or 3 (–7), marginal. Pollen cones terminal on short branchlets, borne in umbellate clusters of 10–25, pendulous at maturity; pollen 2-saccate. Seed cones solitary, shortly pedunculate, erect or ± spreading, ovoid-globose, 2-seeded, maturing in 1st year. Seed scales thick, woody, deciduous at maturity. Bracts adnate to seed scales at base and shed together with them at maturity. Seeds with large, backward projecting wing extending beyond scale margin at maturity. Cotyledons 4–7. 2n = 44*. • One species: China. 1. Pseudolarix amabilis (J. Nelson) Rehder, J. Arnold Arbor. 1: 53. 1919. 金钱松 jin qian song Larix amabilis J. Nelson, Pinaceae 84. 1866; Abies kaempferi Lindley; Chrysolarix amabilis (J. Nelson) H. E. Moore; Laricopsis kaempferi (Lindley) Kent; Pseudolarix fortunei Mayr; P. kaempferi Gordon; P. pourtetii Ferré. Trees to 40 m tall; trunk to 3 m d.b.h.; bark gray-brown, rough, scaly, flaking; crown broadly conical; long branchlets initially reddish brown or reddish yellow, glossy, glabrous, becoming yellowish gray, brownish gray, or rarely purplish brown in 2nd or 3rd year, finally gray or dark gray; short branchlets slow growing, bearing dense rings of leaf cushions; winter buds ovoid, scales free at apex. -

Douglasfirdouglasfirfacts About

DouglasFirDouglasFirfacts about Douglas Fir, a distinctive North American tree growing in all states from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, is probably used for more Beams and Stringers as well as Posts and Timber grades include lumber and lumber product purposes than any other individual species Select Structural, Construction, Standard and Utility. Light Framing grown on the American Continent. lumber is divided into Select Structural, Construction, Standard, The total Douglas Fir sawtimber stand in the Western Woods Region is Utility, Economy, 1500f Industrial, and 1200f Industrial grades, estimated at 609 billion board feet. Douglas Fir lumber is used for all giving the user a broad selection from which to choose. purposes to which lumber is normally put - for residential building, light Factory lumber is graded according to the rules for all species, and and heavy construction, woodwork, boxes and crates, industrial usage, separated into Factory Select, No. 1 Shop, No. 2 Shop and No. 3 poles, ties and in the manufacture of specialty products. It is one of the Shop in 5/4 and thicker and into Inch Factory Select and No. 1 and volume woods of the Western Woods Region. No. 2 Shop in 4/4. Distribution Botanical Classification In the Western Douglas Fir is manufactured by a large number of Western Woods Douglas Fir was discovered and classified by botanist David Douglas in Woods Region, Region sawmills and is widely distributed throughout the United 1826. Botanically, it is not a true fir but a species distinct in itself known Douglas Fir trees States and foreign countries. Obtainable in straight car lots, it can as Pseudotsuga taxifolia. -

Pseudotsuga- Tsuga Forest

Spatial Relationship of Biomass and Species Distribution in an Old-Growth Pseudotsuga- Tsuga Forest Jiquan Chen, Bo Song, Mark Rudnicki, Melinda Moeur, Ken Bible, Malcolm North, Dave C. Shaw, Jerry F. Franklin, and Dave M. Braun ABSTRACT. Old-growth forests are known for their complex and variable structure and function. In a 12-ha plot (300 m x 400 m) of an old-growth Douglas-fir forest within the T. T. Munger Research Natural Area in southern Washington, we mapped and recorded live/dead condition, species, and diameter at breast height to address the following objectives: (1) to quantify the contribution of overstory species to various elements of aboveground biomass (AGB), density, and basal area, (2) to detect and delineate spatial patchiness of AGB using geostatisitcs, and (3) to explore spatial relationships between AGB patch patterns and forest structure and composition. Published biometric equations for the coniferous biome of the region were applied to compute AGB and its components of each individual stem. A program was developed to randomly locate 500 circular plots within the 12-ha plot that sampled the average biomass component of interest on a per hectare basis so that the discrete point patterns of trees were statistically transformed to continuous variables. The forest structure and composition of low, mediate, and high biomass patches were then analyzed. Biomass distribution of the six major'species across the stand were clearly different and scale- dependent. The average patch size of the AGB based on semivariance analysis for Tsuga heterophy/la, Abies amabi/is, A. grandis, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Thuja plicata, and Taxus brevifolia were 57.3, 81.7, 37, 114.6, 38.7, and 51.8 m, respectively.