LDS Ethnic Wards and Branches in the United States: the Advantages and Disadvantages of Language Congregations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relief Society

9. Relief Society The Relief Society is an auxiliary to the priesthood. in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith All auxiliary organizations exist to help Church [1998], 185). members grow in their testimonies of Heavenly The Relief Society was “divinely made, divinely Father, Jesus Christ, and the restored gospel. authorized, divinely instituted, divinely ordained of Through the work of the auxiliaries, members God” ( Joseph F. Smith, in Teachings: Joseph F. Smith, receive instruction, encouragement, and support as 184). It operates under the direction of priest- they strive to live according to gospel principles. hood leaders. 9.1 9.1.3 Overview of Relief Society Motto and Seal The Relief Society’s motto 9.1.1 is “Charity never faileth” Purposes (1 Corinthians 13:8). This prin- ciple is reflected in its seal: Relief Society helps prepare women for the bless- ings of eternal life as they increase faith in Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ and His Atonement; 9.1.4 strengthen individuals, families, and homes through Membership ordinances and covenants; and work in unity to help All adult women in the Church are members of those in need. Relief Society accomplishes these Relief Society. purposes through Sunday meetings, other Relief Society meetings, service as ministering sisters, and A young woman normally advances into Relief welfare and compassionate service. Society on her 18th birthday or in the coming year. By age 19, each young woman should be fully participating in Relief Society. Because of individ- 9.1.2 ual circumstances, such as personal testimony and History maturity, school graduation, desire to continue with The Prophet Joseph Smith organized the Relief peers, and college attendance, a young woman may Society on March 17, 1842. -

GENERAL HANDBOOK Serving in the Church of Jesus Christ Jesus of Church Serving in The

GENERAL HANDBOOK: SERVING IN THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JULY 2020 2020 SAINTS • JULY GENERAL HANDBOOK: SERVING IN THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST LATTER-DAY GENERAL HANDBOOK Serving in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints JULY 2020 JULY 2020 General Handbook: Serving in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 2020 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. Version: 7/20 PD60010241 000 Printed in the United States of America Contents 0. Introductory Overview . xiv 0.0. Introduction . xiv 0.1. This Handbook . .xiv 0.2. Adaptation and Optional Resources . .xiv 0.3. Updates . xv 0.4. Questions about Instructions . xv 0.5. Terminology . .xv 0.6. Contacting Church Headquarters or the Area Office . xv Doctrinal Foundation 1. God’s Plan and Your Role in the Work of Salvation and Exaltation . .1 1.0. Introduction . 1 1.1. God’s Plan of Happiness . .2 1.2. The Work of Salvation and Exaltation . 2 1.3. The Purpose of the Church . .4 1.4. Your Role in God’s Work . .5 2. Supporting Individuals and Families in the Work of Salvation and Exaltation . .6 2.0. Introduction . 6 2.1. The Role of the Family in God’s Plan . .6 2.2. The Work of Salvation and Exaltation in the Home . 9 2.3. The Relationship between the Home and the Church . 11 3. Priesthood Principles . 13 3.0. Introduction . 13 3.1. Restoration of the Priesthood . -

Chippenham YSA Ward Amy Parks

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass RELS 108 Human Spirituality School of World Studies 2015 Chippenham YSA Ward Amy Parks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/rels108 Part of the Religion Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/rels108/36 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of World Studies at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in RELS 108 Human Spirituality by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELS 108 Human Spirituality | PAGE 1 Chippenham YSA Ward by Amy Parks n November 22nd I attended the in attendance. OChippenham YSA Ward sacrament meeting for the 1-3 ‘o clock service. The It was a mellow environment. In the beginning, church is located on 5600 Monument Avenue, there was soft chatter before the sermon Richmond VA. The Bishop who presided was started, but when it started, it was silent and Roland McClean, and the administration of the serious. There were a lot of breaks in between Sacrament speakers were Elder Walton and the announcements with hymns. All the Elder Peterson. After the opening announce- hymns sounded similar to me. They were all ments and singing, Candy Chester taught the about giving thanks since Thanksgiving was lesson of the sermon. right around the corner. It was a reserved and formal feel. The outside appearance looks mediocre. There is simple landscaping, and the church is built The speaker shared an intense story that with brick. There is one grand, white steeple happened to her son. -

In Union Is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1998 In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900 Kathleen C. Haggard Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Haggard, Kathleen C., "In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900" (1998). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 738. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/738 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. " IN UNION IS STRENGTH" MORMON WOMEN AND COOPERATION, 1867-1900 by Kathleen C. Haggard A Plan B thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in History UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1998 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Anne Butler, for never giving up on me. She not only encouraged me, but helped me believe that this paper could and would be written. Thanks to all the many librarians and archival assistants who helped me with my research, and to Melissa and Tige, who would not let me quit. I am particularly grateful to my parents, Wayne and Adele Creager, and other family members for their moral and financial support which made it possible for me to complete this program. Finally, I express my love and gratitude to my husband John, and our children, Lindsay and Mark, for standing by me when it meant that I was not around nearly as much as they would have liked, and recognizing that, in the end, the late nights and excessive typing would really be worth it. -

Clergy Packet

CLERGY SESSION Monday, June 28, 2021 10:00 a.m. Call to Order Bishop John Hopkins Musical Centering Heewon Kim “And Are We Yet Alive” UMH #553 Seating of Designated Laity Chair, Mark Meyers Instructions [ZOOM] Secretary, Wesley Dickson Bishop’s Reflections Bishop John Hopkins Moral and Official Conduct of All Ordained Clergy and Local Pastors Dean of the Cabinet, Jeffry Bross Presentation of Candidates for Ministry Adrienne Stricker and Mary Gay McKinney Conference Relations Report Chair, Mark Meyers Fellowship of Local Pastors Report Chair, Sharon Engert Order of Deacons Report Chair, Adrienne Stricker Order of Elders Report Chair, Paul Lee Board of Ordained Ministry Chairperson’s Report Chair, Mark Meyers Adjournment Bishop John Hopkins Seating of Designated Laity at Clergy Session (Updated 6/2021) MOTION TO BE MADE AS FOLLOWS: Bishop, I move that the laypersons, local pastors and associate members of the annual conference who are members of the Northern Illinois Conference Board of Ordained Ministry be seated within the Clergy Session with voting privileges. And that the following Annual Conference staff persons be allowed to be present during the 2021 Clergy Session: Laura Lopez, Registrar Anne Marie Gerhardt, Director of Communications Marva Andrews – Bishop’s Administrative Assistant TO ALL PERSONS GATHERED HERE TODAY, just a reminder: You can vote at Clergy Session “on matters of ordination, character and conference relations of other clergy” if: • You are a clergy member in full connection; • Or you are a member of the Board of Ordained Ministry You cannot vote at Clergy Session if you are a: • Provisional Member • Associate and Affiliate Clergy Member • Full-time and Part-time Local Pastor • Clergy Members of another annual conference or other Methodist denominations (346.1) • Clergy from other denominations (346.2) • Laity Order of Elders The following are recommended for provisional membership and commissioning as Elder candidates: JI EUN MORI SIEGEL 1724 W. -

1S 2S 3S 4S Cs

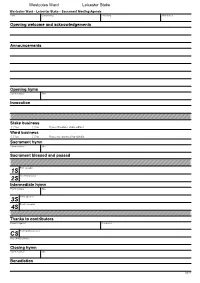

Date Conducting Presiding Attendance Opening welcome and acknowledgements Announcements Opening hymn Hymn number Title Invocation Stake business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes introduce stake officer Ward business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes see overleaf for details Sacrament hymn Hymn number Title Sacrament blessed and passed 1S First speaker 2S Second speaker Intermediate hymn Hymn number Title 3S Third speaker 4S Fourth speaker Thanks to contributors Pianist/organist Conductor CS Concluding speaker Any other business Closing hymn Hymn number Title Benediction 04/12 Date Conducting Presiding Attendance Opening welcome and acknowledgements Announcements Opening hymn Hymn number Title Invocation Stake business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes introduce stake officer Ward business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes see overleaf for details Sacrament hymn Hymn number Title Sacrament blessed and passed Testimonies Bear a brief testimony then invite members of the congregation to bear their testimony and share their faith promoting experiences. Encourage them to keep their testimonies brief so more people may have the opportunity to participate. Thanks to contributors Pianist/organist Conductor Any other business Closing hymn Hymn number Title Benediction 04/12 Releases [Name] has been released as [position], and we propose that he [or she] be given a vote of thanks for his [or her] service. Those who wish to express their appreciation may manifest it by the uplifted hand. Callings Would [name] please stand. [Name] has been called as [position], and we propose that he [or she] be sustained. Those in favour may manifest it by the uplifted hand. [Pause briefly for the sustaining vote.] Those opposed, if any, may manifest it. Ordinations Would [name] please stand. -

Fountain Valley 2Nd Ward

The Church of Jesus Christ Ward Lessons of Latter-Day Saints Date Gospel Doctrine Priesthood & Relief Society March 27th #11 “Press Forward with TFOT – “Ship Shape and Cordata Park Ward a Steadfastness in Christ” Bristol Fashion” - Cook Sacrament Meeting Youth curriculum for Sunday School is at: www.lds.org/youth/learn 27 March 2016 Missionaries from our Ward Presiding……………………….…….………..……….....Bishop Tyler Davis Conducting…………………………………………..….......Brother Jeff Carr Elder Jordan Terry Elder Uy Jun Koo Organist………………………………….......................Sister Rosanne Wells Misión Perú Trujillo Norte New Jersey Morristown Mission Teodoro Valcarcel 512 5 Cold Hill Road South, Suite 10 Chorister……………………………………….....…..….Brother Tom Wells Urb. Primavera Mendham, NJ 07945-3207 Opening Hymn………………………………………….………..Hymn #198 Trujillo, La Libertad [email protected] That Easter Morn Perú Birthday: December 19th [email protected] Birthday: March 6th Invocation………………………..................................Brother John Stebbings Elder Daniel Parker Sister Samantha Lovin Ward Business Colombia Barranquilla Mission Washington Kennewick Mission Calle 82 #55-20, Apto 2 8202 West Quinault Avenue, Suite D Barranquilla Atlantico Kennewick, WA 99336 Sacrament Hymn………………………………....………..……...Hymn #182 Colombia [email protected] Birthday: July 18th Birthday: November 21st We’ll Sing All Hail to Jesus’ Name [email protected] Administration of the Sacrament Elder Joseph Bailey Kekoa Jensen Valentin Nunez (For Elder Travis Schloderer) Kentucky Louisville Mission Rivadavia 599 1325 Eastern Pkwy Quilmes 1878 Youth Speakers: Carolyn Koo Louisville, KY 40204 Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires Kyle Fusco Birthday: June 5th Argentina [email protected] Birthday: September 27th Special Music by the Primary: “Did Jesus Really Live Again?” and [email protected] “Hosanna” Armed Services Amy Crowley (U.S. -

Seventh Ward Chapel HABS NO. U-22 (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints) 116 West Fifth South Street Salt Lake City Salt Lake County Utah

Seventh Ward Chapel HABS NO. U-22 (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) 116 west Fifth South Street Salt Lake City Salt Lake County Utah PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. U-22: SEVENTH WARD CHAPEL 'UTAH.- (CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OP LATTER-DAY SAINTS) \% $Au! Location: 116 West Fifth South Street, . 5%. " " Salt Lake City Salt Lake County Utah Geographic Location Code: 43-1700-035 Latitude: 45° 30'1" N Longitude: 1110 53' 37" W Demolished 1967, Statement of Significance: This was one of the original 19 Ward Chapels in Salt Lake City, Utah. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. Physical History: 1. Original and subsequent owners: Trustees of the 7th School District, Salt lake City, Utah (Pre-1875). William Thorn, Bishop of the 7th Ward of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and his successors (August 18, 1875). m Corporation of Members of the LDS Church residing in the 7th Ecclisiastical Ward of the Salt Lake Stake of Zion (December 9, 1882), Sixth-Seventh Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (October 20, 1938) , Fourth Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (February 2, 1965). 2. Date of erection: Started 1862, completed 1877. 3. Architect and builder: Unknown 4. Notes on original plan and construction of building: The building was originally one large room with a small platform on the north end, and entrances on north and south ends. -

The Minutes OfThe 53Rd Session of the North Carolina Conference Of

The Minutes of The 53rd Session of the North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church Meeting in Annual Conference on June 18, 2020 Due to the COVID-19 health crises, the 2020 Annual Conference was held virtually instead of the Greenville Convention Center as originally planned. At 10:00 a.m., Bishop Hope Morgan Ward welcomed the Annual Conference members. The session opened with a worship service. The Hymn sung throughout the worship was “And Are We Yet Alive?” Musicians were Christopher Jackson, Duda Dial, and Paula Jones. Gary Locklear led an opening prayer. Scripture was read by Donna Banks, Gayle Tabor, Daryl DeCotis, Jason Villegas, and Sang-Seon Park. Jaime Thompson prayed for the families of the clergy and clergy spouses who had died since the last Annual Conference while their names were shown on a slide. This was followed by a litany of lament for the world situation. Bishop Ward was the preacher. A Love Feast was led by Nathan and Laura Wittman. The worship service ended with singing “Lift High the Cross.” Plenary Session The Plenary session was called to order at 10:45 a.m. by Bishop Ward. Cooper Sykes, Conference UMYF president, opened in prayer. Appreciation was expressed for Jerry Bryan and Ellen McCubbin. Conference Secretary Jerry Bryan welcomed the Annual Conference and led the ordering procedures. Ellen McCubbin reviewed the rules and procedures which were previously adopted. She also explained how the rules were created for this unique situation and reminded the Annual Conference that all decisions made would be ratified at the 2021 Annual Conference. -

Ward Callings by Organization

Ward Callings by Organization Bishopric Priests Sunday School Instructor - Course 12 Bishop Priests Quorum President Sunday School Instructor - Course 13 Bishopric First Counselor Priests Quorum First Assistant Sunday School Instructor - Course 14 Bishopric Second Counselor Priests Quorum Second Assistant Sunday School Instructor - Course 15 Ward Clerk Priests Quorum Secretary Sunday School Instructor - Course 16 Ward Assistant Clerk Sunday School Instructor - Course 17 Ward Assistant Clerk--Finance Teachers Ward Assistant Clerk--Membership Teachers Quorum President Primary Ward Executive Secretary Teachers Quorum First Counselor Primary President Teachers Quorum Second Counselor Primary First Counselor High Priests Teachers Quorum Secretary Primary Second Counselor High Priests Group Leader Primary Secretary High Priests Group First Assistant Activities Day Leader Deacons Cub Scouts Committee Chair High Priests Group Second Assistant Deacons Quorum President High Priests Group Secretary Cub Scouts - Committee Member Deacons Quorum First Counselor Cub Scouts - Cubmaster High Priests Group Instructor Deacons Quorum Second Counselor High Priests Home Teaching District Cub Scouts - Webelos Leader Deacons Quorum Secretary Den Leader Supervisor Boy Scouts - Eleven-Year-Old Scout Young Women Leader Elders Young Women President Primary Chorister Elders Quorum President Young Women First Counselor Primary Pianist Elders Quorum First Counselor Young Women Second Counselor Primary Worker Elders Quorum Second Counselor Young Women Secretary Primary -

WAYNE WARD | AUGUST Lessons Inside 41 July 2012 42 Vol

Contains AUGUST Nurturing Faith Lessons HARDY CLEMONS talks about life after loss 38 JULY 2012 baptiststoday.org NEW Vision FITZ HILL BRINGS CHANGE TO COLLEGE, COMMUNITY | 4 Missional Formation Communities reconnect young adults | 32 ™ BIBLE STUDIES The wonder of for adults and youth 17 WAYNE WARD | AUGUST lessons inside 41 July 2012 42 Vol. 30, No. 7 baptiststoday.org John D. Pierce Executive Editor [email protected] Julie Steele Chief Operations Officer [email protected] Jackie B. Riley Managing Editor [email protected] Tony W. Cartledge Contributing Editor [email protected] Bruce T. Gourley Online Editor [email protected] MUSIC DEAN HELPS WITH HORSE-RIDING REHAB FOR CHILDRE N David Cassady Church Resources Editor [email protected] Terri Byrd Contributing Writer PERSPECTIVE Vickie Frayne Christianity, culture and change 9 Art Director John Pierce 34 Jannie Lister Customer Service Manager [email protected] What should we do with truth — or let truth do with us? 14 Kimberly L. Hovis Marketing Associate Jimmy Spencer Jr. [email protected] Walker Knight, Publisher Emeritus Organizing the church around its purpose 15 Jim Somerville Jack U. Harwell, Editor Emeritus BOARD OF DIRECTORS Whitsitt Society continues mission Ministry couples find fulfillment Walter B. Shurden, Macon, Ga. (chairman) through news journal 31 Robert Cates, Rome, Ga. (vice chair) amid balancing act Jimmy R. Allen, Big Canoe, Ga. Loyd Allen Nannette Avery, Signal Mountain, Tenn. Kelly L. Belcher, Spartanburg, S.C. Thomas E. Boland, Alpharetta, Ga. Cover photo: By John Pierce. Arkansas Baptist IN THE NEWS Donald L. Brewer, Gainesville, Ga. College President O. Fitzgerald Hill is restoring Huey Bridgman, The Villages, Fla. -

Doctrine and Covenants and Church History Gospel Doctrine Teacher’S Manual Doctrine and Covenants and Church History

Doctrine and Covenants and Church History Gospel Doctrine Teacher’s Manual Doctrine and Covenants and Church History Gospel Doctrine Teacher’s Manual Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Comments and Suggestions Your comments and suggestions about this manual would be appreciated. Please submit them to: Curriculum Planning 50 East North Temple Street, Floor 24 Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3200 USA E-mail: [email protected] Please list your name, address, ward, and stake. Be sure to give the title of the manual. Then offer your comments and suggestions about the manual’s strengths and areas of potential improvement. Cover: The First Vision, by Del Parson Page 151: Saints Driven from Jackson County Missouri, by C. C. A. Christensen © by Museum of Fine Arts, Brigham Young University. All rights reserved Page 184: Brother Joseph, by David Lindsley Page 192: Brigham Young, America’s Moses, by Kenneth A. Corbett © by Kenneth A. Corbett © 1999 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 8/96 Contents Lesson Number and Title Page Helps for the Teacher v 1 Introduction to the Doctrine and Covenants and Church History 1 2 “Behold, I Am Jesus Christ, the Savior of the World” 6 3 “I Had Seen a Vision” 11 4 “Remember the New Covenant, Even the Book of Mormon” 16 5 “This Is the Spirit of Revelation” 24 6 “I Will Tell You in Your Mind and in Your Heart, by the Holy Ghost” 29 7 “The First Principles and Ordinances of the Gospel” 35 8The Restoration of the Priesthood 41 9 “The Only True and Living Church” 48 10 “This Is My Voice unto All” 53 11 “The Field Is White Already to Harvest” 58 12 “The Gathering of My People” 63 13 “This Generation Shall Have My Word through You” 69 14 The Law of Consecration 75 15 “Seek Ye Earnestly the Best Gifts” 81 16 “Thou Shalt .