Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuition Fall 2018 Prepared By: Stephanie Bertolo, Vice President

POLICY PAPER Tuition Fall 2018 Prepared by: Stephanie Bertolo, Vice President Education McMaster Students Union, McMaster University Danny Chang, Vice President University Students’ Council, Western University Catherine Dunne, Associate Vice President University Students’ Council, Western University Matthew Gerrits, Vice President Education Federation of Students, University of Waterloo Urszula Sitarz, Associate Vice President Provincial & Federal Affairs McMaster Students Union, McMaster University With files from: Colin Aitchison, Former Research & Policy Analyst Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance Mackenzie Claggett, Former Research Intern Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance Martyna Siekanowicz Research & Policy Analyst Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance Alexander “AJ” Wray, former Chair of the Board Federation of Students, University of Waterloo 2 ABOUT OUSA OUSA represents the interests of 150,000 professional and undergraduate, full-time and part-time university students at eight student associations across Ontario. Our vision is for an accessible, affordable, accountable, and high quality post-secondary education in Ontario. To achieve this vision we’ve come together to develop solutions to challenges facing higher education, build broad consensus for our policy options, and lobby government to implement them. OUSA’s Home Office is located on the traditional Indigenous territory of the Huron- Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and most recently, the territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit River. This territory is part of the Dish with One Spoon Treaty, an agreement between the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and allied nations to peaceably share and care for the resources around the Great Lakes. This territory is also covered by Treaty 13 of the Upper Canada Treaties. This Tuition Policy Paper by the Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

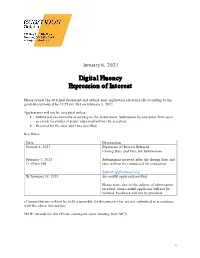

Digital Fluency Expression of Interest

January 6, 2021 Digital Fluency Expression of Interest Please review the attached document and submit your application electronically according to the guidelines provided by 11:59 pm EST on February 3, 2021. Applications will not be accepted unless: • Submitted electronically according to the instructions. Submission by any other form such as email, facsimiles or paper copy mail will not be accepted. • Received by the date and time specified. Key Dates: Date Description January 6, 2021 Expression of Interest Released Closing Date and Time for Submissions February 3, 2021 Submissions received after the closing date and 11:59pm EST time will not be considered for evaluation Submit applications here By February 28, 2021 Successful applicants notified Please note: due to the volume of submissions received, unsuccessful applicants will not be notified. Feedback will not be provided eCampusOntario will not be held responsible for documents that are not submitted in accordance with the above instructions NOTE: Awards for this EOI are contingent upon funding from MCU. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................... 3 2. DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 WHAT IS DIGITAL FLUENCY? .......................................................................................................... 4 3. PROJECT TYPE ..................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2016-17 Table of Contents Message from the Board Co-Chairs

Annual Report 2016-17 Table of Contents Message from the Board Co-Chairs........................... 01 Mobility Infrastructure.................................................... 21 Message from the Executive Director........................ 04 Pathway Development Why Mobility Matters..................................................... 07 Knowledge Gathering Who We Are Learning Outcomes Strategic Priorities Transfer Banter................................................................. 25 Our Partners Committees...................................................................... 29 Students First................................................................... 11 Board of Directors.......................................................... 31 Building on Shared Resources..................................... 17 The ONCAT Team........................................................... 32 Bringing Our Identity Full Circle Platforms for Collaboration ONTransfer.ca Website Redesign Message from the Board Co-Chairs This is an exciting year for the postsecondary system serving on ONCAT’s Board of Directors, it really has been and one in which Ontario’s colleges celebrate their a pleasure to be involved with an organization committed 50th anniversary. Throughout these past decades, to not only supporting the partnership aspirations of postsecondary education as a system and the relationship institutions, but also involving students and government in of colleges and universities, has evolved to one of a collective effort to expand student -

Services Available for Students with Lds at Ontario Colleges and Universities

Services Available for Students with LDs at Ontario Colleges and Universities Institution Student Accessibilities Services Website Student Accessibilities Services Contact Information Algoma University http://www.algomau.ca/learningcentre/ 705-949-2301 ext.4221 [email protected] Algonquin College http://www.algonquincollege.com/accessibility-office/ 613-727-4723 ext.7058 [email protected] Brock University https://brocku.ca/services-students-disabilities 905-668-5550 ext.3240 [email protected] Cambrian College http://www.cambriancollege.ca/AboutCambrian/Pages/Accessibilit 705-566-8101 ext.7420 y.aspx [email protected] Canadore College http://www.canadorecollege.ca/departments-services/student- College Drive Campus: success-services 705-474-7600 ext.5205 Resource Centre: 705-474-7600 ext.5544 Commerce Court Campus: 705-474-7600 ext.5655 Aviation Campus: 705-474-7600 ext.5956 Parry Sound Campus: 705-746-9222 ext.7351 Carleton University http://carleton.ca/accessibility/ 613-520-5622 [email protected] Centennial College https://www.centennialcollege.ca/student-life/student- Ashtonbee Campus: services/centre-for-students-with-disabilities/ 416-289-5000 ext.7202 Morningside Campus: 416-289-5000 ext.8025 Progress Campus: 416-289-5000 ext.2627 Story Arts Centre: 416-289-5000 ext.8664 [email protected] Services Available for Students with LDs at Ontario Colleges and Universities Conestoga College https://www.conestogac.on.ca/accessibility-services/ 519-748-5220 ext.3232 [email protected] Confederation -

OCAD University At-Large Faculty Senator Elections 2016 List of Candidates

OCAD University At-Large Faculty Senator Elections 2016 List of Candidates: Michelle Astrug (Faculty of Design) Michelle Astrug is a tenure-track Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Design, teaching in Graphic Design. She is applying for senate because she is interested in actively participating in University governance. Claire Brunet (Faculty of Art) Claire Brunet is a sculptor and Associate Professor in Media and installation art; Sculpture/Installation program and Fabrication Studio Bronze Casting and Digital Processes at OCAD University in Toronto. In June 2014 Brunet completed a PhD degree in Fine Arts, in the Interdisciplinary Program (INDI) at Concordia University in Montreal. Her research work explores expanded spatial boundaries and the influence of a 3D digital and technological context on the artist’s creative process in sculpture practice. Brunet’s sculpture project proposes opposing temporal forces—a 3D digital and technological spatial approach as a mode of production, in opposition to a critical discourse in regard to living species and their relation to their natural environment—which stresses the opposing values of an hypermodern society (Lipovetsky 2005). Brunet has presented projects and papers at conferences in New Zealand, Australia, Belgium, Germany, Greece and Canada. Her publications include: Exploring Data Space, in The Faculty of Art Newsletter (OCAD U, Toronto, 2012); “Extending Spatial Boundaries Through Sculpture Practices: Exploring Natural and 3D Technological Environments” in The International Journal of the Arts in Society (Illinois: CG Publishing, 2012); McLuhan and Extended Environment: Affect and Effect of a 3D Digital Medium on Sculpture Practice, in Y. Van Den Eede, J. Bauwens, J. Beyl, M. -

Does Accreditation Matter for Art & Design Schools in Canada?

College Quarterly Winter 2013 - Volume 16 Number 1 (../index.html) Does Accreditation Matter for Art & Design Schools in Canada? Home By Reiko (Leiko) Shimizu (../index.html) Studio-based degrees in fine arts and design are not often written Contents about in higher education literature. Perhaps it is because art and design (index.html) education is misunderstood – students are viewed as “finding themselves” or have unrealistic dreams of becoming the next big artist. Perhaps the studio-based nature of the curriculum does not intrigue researchers to write about issues that concern it, or perhaps it is because anyone can call themself an artist without having an academic credential. Ten years ago, urban theorist Richard Florida coined the term the “creative class” as individuals who “do a wide variety of work in a wide variety of industries – from technology to entertainment, journalism to finance, high- end manufacturing to the arts….they share a common ethos that values creativity, individuality, difference, and merit” (Florida, 2002, para. 8). According to Florida the creative class helps build economic development; therefore, our cities should be nurtured to be more inviting to these types of individuals. This emphasis on culture and creativity is at the foundation of art and design education. Groys (2009) argues that art education is complicated and subjective; it ultimately has no rules and that “teaching art means teaching life” (as cited in Madoff, 2009, p. 27). If that is the case, how does one measure quality in a field that is viewed as so subjective? How does one define and value art and design education? One’s notion of good art and design can be vastly different from another’s, and both views may come from experts in the field. -

Mcmaster Students Union Vice-President

McMaster Students Union Vice-President (Education) Transition Report Written by Ryan Deshpande, Vice-President (Education) 2017-18 For Stephanie Bertolo, Vice-President (Education) 2018-19 Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................. 2 Foreword .............................................................................................................................................5 MSU – Internal ................................................................................................................................... 6 Operating Policies and Bylaws ................................................................................................. 6 Board of Directors ........................................................................................................................ 7 Executive Board ........................................................................................................................... 8 Student Representative Assembly .......................................................................................... 9 Education and Advocacy Department.................................................................................. 10 Associate Vice Presidents .......................................................................................................... 11 Associate Vice-President (University Affairs) .................................................................. -

Welcome! SPOTLIGHT

From: Research Office To: All Academic Administrators; All Administrative Staff & Managers; All Deans & Associate Deans; All Faculty Subject: PULSE: Research & Innovation Newsletter, October 2020 Date: October 2, 2020 10:59:33 AM Attachments: image008.png image011.png image014.png October 2020 Welcome! The Office of Research & Innovation supports research and scholarly activity at OCAD University. We help OCAD U researchers to find funding, develop projects and partnerships and engage students. Contact us today to learn more about how we can support you in all things research at OCAD University. The OCAD U Research Ethics Board (REB) provides an independent, impartial, and equitable ethics review of all research at OCAD U that involves human participants. Learn more about the REB and its processes here. **If you require information published in this newsletter in an alternate format, please forward your request to [email protected] and let us know what format is preferable. We will provide you with an accessible version.** SPOTLIGHT Meet Kathy Moscou Assistant Professor Kathy Moscou’s research of pharmacogovernance and comparative health policy addresses equity in drug safety and governance to foster healthy communities. Recent community- based participatory action research with Indigenous youth explored their perspectives on success, leadership and the intersectionality between holistic health and a healthy neighborhood. Her Urban Garden project was a community-based research partnership with Indigenous organizations in Winnipeg and Brandon, Manitoba. The goal of the project was to improve the health and wellbeing of Indigenous youth by identifying culturally relevant indicators for holistic health. The research also investigated the holistic health benefits of urban gardening for individuals and neighbourhoods. -

Pathways and Barriers to Art and Design Undergraduate Education for Students with Previous College and University Experience

PATHWAYS AND BARRIERS TO ART AND DESIGN UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION FOR STUDENTS WITH PREVIOUS COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY EXPERIENCE Prepared for: Ontario Council on Articulation and Transfer by: Deanne Fisher Eric Nay Mary Wilson Laura Wood OCAD University November 2012 ABSTRACT OCAD University undertook an investigation of the transition needs and experiences of current OCAD U students from two distinct types of educational backgrounds: those with previous undergraduate coursework and those with prior college experience. The study used a mixed method approach, both qualitative (analysis of semi-structured interviews with students from both cohorts) and quantitative (analysis of National Survey of Student Engagement data comparing college transfer students, university transfer students and students who came directly from high school). The study pointed to some significant differences in the expectations, experiences and needs of students from different educational backgrounds leading to a series of recommendations to better facilitate student mobility and enhance the quality of experience. While focused in one institutional environment, many of the findings can be generalized to fine and applied art and student mobility within studio-based programs. RESEARCH TEAM Deanne Fisher (Principal Investigator) Associate Vice-President, Students Interview Coordinator: OCAD University Polly Buechel, OCAD University Eric Nay Associate Dean & Professor, Faculty of Liberal Data Analysis: Arts & Sciences Holly Kristensen, James D.A. Parker, Robyn OCAD University Taylor, Trent University Mary Wilson Laura Wood, Director, Centre for Innovation in Art & Design OCAD University Education OCAD University Research Assistants: Elizabeth Coleman Laura Wood Linh Do Manager, Institutional Analysis Faysal Itani OCAD University Fareena Chanda OCAD University is grateful for the support of the Ontario Council on Articulation and Transfer (formerly College-University Consortium Council) in funding this project. -

Honours Bachelor of Arts: Visual and Critical Studies

Honours Bachelor of Arts: Visual and Critical Studies Application for Revision to Ministerial Consent Date of Submission: January 14, 2013 OCAD UNIVERSITY _____________________________________________________________________________________ OCAD University Honours Bachelor of Arts in Visual and Critical Studies 2 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Organization and Program Information 1.1.1 Title Page for Submission NAME OF ORGANIZATION: Ontario College of Art & Design University OCAD University URL FOR THE ORGANIZATION: www.ocadu.ca PROPOSED DEGREE NOMENCLATURE: Honours Bachelor of Arts (Visual and Critical Studies) LOCATION OF PROGRAM: OCAD University Campus 100 McCaul Street Toronto, ON M5T 1W1 1.1.2 Contact Information: i. Person Responsible for this Submission: Kathryn Shailer, PhD Dean, Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies OCAD University 100 McCaul Street Toronto, ON M5T 1W1 Tel: 416-977-6000, Ext. 318 Fax: 416-977-0235 [email protected] ii. Site Visit Coordinator: Same _____________________________________________________________________________________ OCAD University Honours Bachelor of Arts in Visual and Critical Studies 3 1.1.3 Quality Assessment Panel Nominees NAME OCCUPATION & CREDENTIALS CONTACT INFO EMPLOYER Mark Cheetham Professor, PhD, History of Art [email protected] Department of Art, (University of University of Toronto London); MA, Philosophy (University of Toronto) Brian Foss Professor and PhD, Art History [email protected] Director, MA (Concordia) School of Studies in -

A Joint Publication on Campus Sexual Violence Prevention and Response

Shared Perspectives: A Joint Publication on Campus Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Alliance of BC Students College Student Alliance Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance Union étudiante du Québec New Brunswick Student Alliance Students Nova Scotia University of Prince Edward Island Student Union Canadian Alliance of Student Associations contents MESSAGE FROM THE PARTNERS 3 ALLIANCE OF BC STUDENTS 4 COLLEGE STUDENT ALLIANCE 10 ONTARIO UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT ALLIANCE 16 UNION ÉTUDIANTE DU QUÉBEC 24 NEW BRUNSWICK STUDENT ALLIANCE 28 STUDENTS NOVA SCOTIA 32 UNIVERSITY OF PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND 38 STUDENT UNION CANADIAN ALLIANCE OF STUDENT 42 ASSOCIATIONS SOURCES CITED 46 2 MESSAGE FROM THE PARTNERS Last summer, a partnership of provincial student associations published Shared Perspectives: A Joint Publication on Student Mental Health. That publication marked a national review of the challenges of student mental health care and identified examples of limited successes. This Spring, our partnership comes together again to address another important issue in post-secondary education with Shared Perspectives: A Joint Publication on Campus Sexual Violence Prevention and Response. Everyday, our organizations think about how post-secondary education can continue to improve in Canada. We work to make sure all students can afford to pursue higher education, and how to prevent barriers to access. We care about the high-quality and innovative education we are receiving, and are constantly looking for areas of growth. We think about how to incorporate the student voice into education, ensuring that our sectors are accountable to the students they serve. In addition to these efforts, we also acknowledge that students must have a strong foundation of health and safety to be successful during their education. -

Ouinfo 2019–2020 1 Table of Contents

Last Updated: September 10, 2019 | OUInfo 2019–2020 1 Table of Contents Western University – Huron University College .....................................................303 Table of Contents Western University – King's University College .....................................................304 Wilfrid Laurier University – Brantford Campus.......................................................305 About OUInfo ............................................................................. 4 Wilfrid Laurier University – Waterloo Campus .......................................................305 University of Windsor .............................................................................................306 Subject Area Chart .................................................................... 5 York University .......................................................................................................306 Degree Abbreviations................................................................................................ 5 York University – Glendon Campus .......................................................................307 Common Course Codes.......................................................... 18 Campus Visits and Events ................................................... 308 Algoma University ..................................................................................................308 Admission Guidelines and Programs of Study .................... 19 Brock University .....................................................................................................308