Touch of Evil (1958)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touch of Evil (Sed De Mal, 1958) Orson Welles

Especial: Cinema Negre | 13 denovembre de 2014 | Horari: 20.00 i 22.30 h Touch of Evil (Sed de mal, 1958) Orson Welles Sinopsi Un agent de policia, Heston, arriba a la frontera mexicana amb la seva dona, just al moment que explota una bomba. “Vamos, lee mi futuro. Tú no otros virtuosos desplazamien- Fitxa artística tienes ninguno. ¿Qué quieres tos de cámara (...). decir? Su futuro está agota- Welles y su director de foto- do.” Así habla una adivina, grafía, Russell Metty, no que- Charlton Heston ........Mike Vargas interpretada por Marlene Die- rían solo lucirse. Los destinos Janet Leigh .............Susan Vargas trich, al sheriff borracho de de todos los personajes prin- una ciudad fronteriza, inter- Orson Welles ...........Hank Quinlan cipales están enmarañados de pretado por Orson Welles, en principio a fin, y la fotografía Joseph Calleia ..........Pete Menzies Touch of Evil. lo consigue reflejar atrapán- Esas palabras resuenan tristes, dolos en las mismas tomas, o ya que Welles no volvería a conectándolos a través de cor- dirigir en Hollywood después tes que responden y resuenan. de hacer esta historia oscura La historia no avanza en línea y atmosférica de la delincuen- recta, sino como una serie de cia y la corrupción. bucles y espirales. Fitxa tècnica Fue nombrada mejor película Algunos de esos bucles fue- en la Feria Mundial de Bruse- ron retirados cuando Univer- Director . Orson Welles las (Godard y Truffaut estaban sal Studios tomó y reeditó la Guió ................Orson Welles en el jurado) de 1958, pero película de Welles, añadien- Basat en la novel·la Franklin Coen en América se estrenó en un do primeros planos y acortan- Productor ...........Albert Zugsmith programa doble, falló, y puso do escenas, por lo que existía Música original. -

Mustang Daily, January 10, 1975

Mustang Daly Volume 39: Number 2 California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Friday, January 10, 1975 Group claims state colleges Suit charges are slighted • Funding policies racial bias called unjustified BY TOM McCABtIiY at Cal Poly Controversy is growing as a group persists in its attempts to win more money for the system by MARK GROSSI from the State Education fund. Cal Poly has been charged with According to Acala, the whole The Committee for Equal racial discrimination against state university and colleges Treatment in Higher Education Mexican-American employees in system will oe affected by the (CETHE) is gaining recognition a class action suit filed Thursday decision. as it continues to publicize its in San Francisco U.S. District “We were looking for the best belief that each student who Court by the Mexican-American case to bring to court. Cal Poly attends a branch of the Legal Defense and Education represents the best case of University of California (UC) Fund (MALDEF). discrimination in the California annually receives close to $300 The case cited in the suit is that state university and colleges more than do students who are of Dr. Manuel Guerra, demoted sytem.” enrolled in comparable programs head of Poly’s Foreign Language Guerra was demoted from at a state college or university. Department. According to Carlos photo by DAVID STUBBS department head, the suit According to CETHE co Alcala, national director of charges, after Kennedy learned founder J. William Leasure, the educational litigation for he had filed a complaint with the discrepency in funding is due to Steve Archer sings praises to God in a performance here MALDEF, $810,000 in damages Thursday. -

Old Loves Bloom, New Romances Bud Coordinate School

tHGH SCHOOL LIB DARIEN, rONN. \iiiiiiiiI.-. Volume LXXV, Number 7 Darien High School, Darien, Connecticut February 11, 1975 Committee To Examine Options, Coordinate School Involvement mittee on Options or Coordinating By SUE ALLARD Committee comprised ofstaffmembers Open-ended morning, co-op teaching, and students whose duty it will be to alternative high school programs,final oversee the entire operation. According ..: exams, and a pass·fail optionfor a sixth to Mr. Catania, members of the Com ;; subject are but a few ofthe possible sub mittee on Options will not necessarily jects open for investigation and action do the work in individualcommittees: by separatecommittees under a new ad "Its object is to try to give overall direc hoc committee associated with the tion and c<HJrdination to all activities." School Council. "With imagination and co-operative In addition to Mrs. Marshall as effort we could get a lot of things done chairperson of the Coordinating Com that we'd like to do," stated Salvatore mittee, other faculty members include: Jose Leon and Christl Anastasio of the Foreign Language Department Catania, DHS principal. This new William Jacobs, John Rallo, James both are organizing excursions abroad during April vacation. system, a network of committees, was Nicholson, Donald MacAusland, Jim Clark) introduced at a recent faculty meeting. David Herbert, Joan Walsh, Matthew Many teachers have expressed a desire Tirrell, David Hartkopf, and Marjorie Teachers To Lead Tours to become involved in different Ro demann. Mr. Catania will serve as programs. This system is designed to an ex-officio member. try to get some objectives realized by Four seniors and two juniors, from Europe - A 'Great Escape' providing "an effective mechanism to both the School Council and Neirad, support and coordinate these ideas and will also serve on the Coordinating Several members of the faculty have During April vacation Jose Leon of integrate projects into the existing Committee. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

The Ithacan, 1977-11-03

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1977-78 The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 11-3-1977 The thI acan, 1977-11-03 The thI acan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1977-78 Recommended Citation The thI acan, "The thI acan, 1977-11-03" (1977). The Ithacan, 1977-78. 11. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1977-78/11 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1977-78 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ), NOV 4 1977 Nov~r~Ll~Zl ,.. LIBRAAY Vol. 51 /a>~~dil:lal~ Ithaca College published independently by the students of Ithaca College Ithaca, New York CONGRESS. SAYS NO TO COLBY by Corey Taylor was willing to accept, because of appear. The debate raged on for Vincent Belligosi, you have to Student Congress, with its her public position against Colby. LC. Student Ron Chuger about two hours. In addressing pay them too." Morton retorted, largest turnout· all year, voted Brown remained in the chair for man rapped Altschuler saying, the issue of free speech. Dick "It misses the point to compare 33-13, to cancel an invitation to the meeting, as no one accepted. "he doesn't know what he's Lory stated, "the people with the Colby with GregQry, you are former CIA direstor William Brown set down strict rules talking about, l'd like a crack at power like Colby say no, you comparing the oppressor and the Colby for an appearance at concerning the order of speakers him" (in reference to Colby). -

October 9, 2012 (XXV:6) David Miller, LONELY ARE the BRAVE (1962, 107 Min)

October 9, 2012 (XXV:6) David Miller, LONELY ARE THE BRAVE (1962, 107 min) Directed by David Miller Screenplay by Dalton Trumbo Based on the novel, The Brave Cowboy, by Edward Abbey Produced by Edward Lewis Original Music by Jerry Goldsmith Cinematography by Philip H. Lathrop Film Editing by Leon Barsha Art Direction by Alexander Golitzen and Robert Emmet Smith Set Decoration by George Milo Makeup by Larry Germain, Dave Grayson, and Bud Westmore Kirk Douglas…John W. "Jack" Burns Gena Rowlands…Jerry Bondi Walter Matthau…Sheriff Morey Johnson Michael Kane…Paul Bondi Carroll O'Connor…Hinton William Schallert…Harry George Kennedy…Deputy Sheriff Gutierrez Karl Swenson…Rev. Hoskins William Mims…First Deputy Arraigning Burns Martin Garralaga…Old Man Lalo Rios…Prisoner Bill Bixby…Airman in Helicopter Bill Raisch…One Arm Table Tennis, 1936 Let's Dance, 1935 A Sports Parade Subject: Crew DAVID MILLER (November 28, 1909, Paterson, New Jersey – April Racing, and 1935 Trained Hoofs. 14, 1992, Los Angeles, California) has 52 directing credits, among them 1981 “Goldie and the Boxer Go to Hollywood”, 1979 “Goldie DALTON TRUMBO (James Dalton Trumbo, December 9, 1905, and the Boxer”, 1979 “Love for Rent”, 1979 “The Best Place to Be”, Montrose, Colorado – September 10, 1976, Los Angeles, California) 1976 Bittersweet Love, 1973 Executive Action, 1969 Hail, Hero!, won best writing Oscars for The Brave One (1956) and Roman 1968 Hammerhead, 1963 Captain Newman, M.D., 1962 Lonely Are Holiday (1953). He was blacklisted for many years and, until Kirk the Brave, 1961 Back Street, 1960 Midnight Lace, 1959 Happy Douglas insisted he be given screen credit for Spartacus was often to Anniversary, 1957 The Story of Esther Costello, 1956 Diane, 1951 write under a pseudonym. -

DESERT SKY CINEMS CLASSIC FILM SERIES Miscellaneous

DESERT SKY CINEMS CLASSIC FILM SERIES Miscellaneous Musicals • Gypsy (1962) 2:52 Tuesday Aug. 20 • Westside Story (1961) 2:32 Tuesday Aug. 27 • An American in Paris (1951) 1:55 Tuesday Sept. 3 • Singing in the Rain (1952) 1:03 Tuesday Sept. 10 • Camelot (1960) 2:59 Tuesday Sept. 17 • Gigi (1973) 1:59 Tuesday Sept. 24 War is Hell • Patton (1970) 2:51 Tuesday Oct. 1 • The Bridge over the River Kwai (1957) 2:47 Tuesday Oct. 8 • M*A*S*H (1970) 1:56 Tuesday Oct. 15 • Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) 3:05 Tuesday Oct. 22 • Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) 2:25 Tuesday Oct. 29 • Sergeant York (1941) 2:14 Tuesday Nov. 5 • Midway (1976) 2:22 Tuesday Nov. 12 • In Harms in Way (1965) 2:47 Tuesday Nov. 19 Hitchcock Presents • Rear Window (1954) 1:15 Tuesday Nov. 26 • Vertigo (1958) 2:09 Tuesday Dec. 3 • North by Northwest (1959) 2:16 Tuesday Dec. 10 • The Birds (1963) 1:59 Tuesday Dec. 17 • Psycho (1960) 1:49 Tuesday Dec. 24 • Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) 1:15 Tuesday Dec. 31 2014 The Sixties • Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 1:55 Tuesday Jan. 7 • Easy Rider (1969) 1:35 Tuesday Jan. 14 • To Sir With Love (1967) 1:45 Tuesday Jan. 21 • The Apartment (1960) 2:05 Tuesday Jan. 28 • To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) 2:10 Tuesday Feb. 4 • The Manchurian Candidate (1962) 2:09 Tuesday Feb. 11 • The Hustler (1961) 2:15 Tuesday Feb. 18 A Tribute to Jimmy Stewart • Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) 2:09 Tuesday Feb. -

Reading in the Dark: Using Film As a Tool in the English Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 446 CS 217 685 AUTHOR Golden, John TITLE Reading in the Dark: Using Film as a Tool in the English Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3872-1 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 199p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 38721-1659: $19.95, members; $26.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classroom Techniques; *Critical Viewing; *English Instruction; *Film Study; *Films; High Schools; Instructional Effectiveness; Language Arts; *Reading Strategies; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Film Viewing; *Textual Analysis ABSTRACT To believe that students are not using reading and analytical skills when they watch or "read" a movie is to miss the power and complexities of film--and of students' viewing processes. This book encourages teachers to harness students' interest in film to help them engage critically with a range of media, including visual and printed texts. Toward this end, the book provides a practical guide to enabling teachers to ,feel comfortable and confident about using film in new and different ways. It addresses film as a compelling medium in itself by using examples from more than 30 films to explain key terminology and cinematic effects. And it then makes direct links between film and literary study by addressing "reading strategies" (e.g., predicting, responding, questioning, and storyboarding) and key aspects of "textual analysis" (e.g., characterization, point of view, irony, and connections between directorial and authorial choices) .The book concludes with classroom-tested suggestions for putting it all together in teaching units on 11 films ranging from "Elizabeth" to "Crooklyn" to "Smoke Signals." Some other films examined are "E.T.," "Life Is Beautiful," "Rocky," "The Lion King," and "Frankenstein." (Contains 35 figures. -

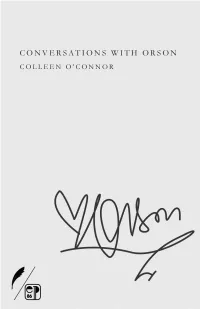

Oconnor Conversations Spread

CONVERSATIONS WITH ORSON COLLEEN O’CONNOR #86 ESSAY PRESS NEXT SERIES Authors in the Next series have received finalist Contents recognition for book-length manuscripts that we think deserve swift publication. We offer an excerpt from those manuscripts here. Series Editors Maria Anderson Introduction vii Andy Fitch by David Lazar Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison War of the Worlds 1 Courtney Mandryk Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, 1938 Victoria A. Sanz Travis A. Sharp The Third Man 6 Ryan Spooner Vienna, 1949 Alexandra Stanislaw Citizen Kane 11 Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Xanadu, Florida, 1941 Christopher Liek Emily Pifer Touch of Evil 17 Randall Tyrone Mexico/U.S. Border, 1958 Cover Design Ryan Spooner F for Fake 22 Ibiza, Spain, 1975 Composition Aimee Harrison Acknowledgments & Notes 24 Author Bio 26 Introduction — David Lazar “Desire is an acquisition,” Colleen O’Connor writes in her unsettling series, Conversations with Orson. And much of desire is dark and escapable, the original noir of noir. The narrator is and isn’t O’Connor. Just as Orson is and isn’t Welles. Orson/O’Connor. O, the plasticity of persona. There is a perverse desire to be both known and unknown in these pieces, fragments of essay, prose poems, bad dreams. How to wrap around a signifier that big, that messy, spilling out so many shadows! Colleen O’Connor pierces her Orson Welles with pity and recognition. We imagine them on Corsica thanks to a time machine, her vivid imagination, and a kind of bad cinematic hangover. The hair of the dog is the deconstruction of the male gaze.