A Guide to St Margaret's Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elm House Farm Burleydam

Elm House Farm Burleydam An attractive period farmhouse, traditional and modern farm buildings and pasture land. 6.2 Acres (2.51Ha) (Additional land may be available by negotiation) Impressive farmhouse with potential for improvement and modernisation Three reception rooms, kitchen, utility, office, cellar Four bedrooms, family bathroom Lawned gardens Range of traditional brick buildings with potential for alternative uses, subject to planning permission Barbers Rural Consultancy LLP Smithfield House, Smithfield Road, Modern portal-framed farm buildings including loose housing, Market Drayton, Shropshire. TF9 1EW cubicle housing and general purpose storage Huge potential for diversification 01630 692500 www.barbers-rural.co.uk Burleydam is situated in a popular area on the North Shropshire/South Cheshire border which is much sought-after as it enjoys all the benefits of rural living in a most attractive and peaceful setting whilst being in close proximity of a number of villages, towns and cities. To the east is Audlem, a charming country village which has a range of facilities including doctors’ surgery, chemist, primary school, public houses, small supermarket and a range of bespoke shops. The farm is within close proximity of The Combermere Arms, an award-winning pub well-known locally for its excellent food and beer. To the north is the charming market town of Nantwich which has a plentiful range of boutique-style shops and more comprehensive range of facilities. Further amenities can be found in Market Drayton and Whitchurch. The nearby towns of Crewe, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Shrewsbury and Chester all offer further services along with railway and motorway links to larger conurba- tions. -

2011 Bluebell Express Newsletter

20 bluebellexpress News of the Bluebell Recovery Project throughout SPRING 11 The Mersey Forest and Cheshire Funding adds a splash of colour to the countryside! The Cheshire Bluebell Recovery Project was set up in 1996 in direct response to the increasing loss of one of our most beautiful woodland wildflowers. The native English bluebell Hyacinthoides non-scripta, is in decline across the UK. To help safeguard its future in Cheshire, this native bluebell has been classified as a local Biodiversity Action Plan species, under the Cheshire region Biodiversity Action Plan (CrBAP). Threats include: project a boost to continue propagation loss of woodland habitat, and, over the next two years, plant these bulbs into local community illegal collectionof wild bulbs, for sale woodlands across the Cheshire region. damage to plants, caused by the trampling of leaves Working with local community groups the Cheshire Bluebell Recovery Project hybridisation with the non-native will be working to plant propagated Spanish bluebell Hyacinthoides hispanica. bulbs in 14 woodlands. If you are part of a local community group and would like Cheshire Wildlife Trust, along withThe to join us in this project please contact: Mersey Forest and RECORD, are actively Sarah Bennett, Cheshire region Biodiversity promoting the English bluebell within Manager [email protected]. Cheshire. Over the last six years this unique project has helped to conserve our native bluebell, by propagating... To find out more: about the: from local seed... thousands of new Cheshire Bluebell Recovery Project: bulbs at the Barrowmore Estate. www.record-lrc.co.uk/c1.aspx?Mod=Article &ArticleID=bluebellhomepage. -

Application No: 12/3007N Location: Lower Farm, WHITCHURCH ROAD

Application No: 12/3007N Location: Lower Farm, WHITCHURCH ROAD, BURLEYDAM, SY13 4AT Proposal: Conversion of existing redundant milking barns to create 9 residential units and subdivision of the existing farmhouse into 2 separate residential units (equating to 11 dwellings on site), with associated works Applicant: I Barton Expiry Date: 27-Nov-2012 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATION: Approve with Conditions MAIN ISSUES: - The impact upon the character and appearance of the barns and the open countryside - The impact upon neighbouring residential amenity - The impact upon Protected Species - The impact upon the highway network - Assessment of potential alternative uses for the barns - The impact upon the future occupiers of the barns REFERRAL The application has been referred to Southern Planning Committee as it is a development which would result in the creation of 11 dwellings. DESCRIPTION OF SITE AND CONTEXT The site is located on the southern side of Whitchurch Road, Burleydam within the open countryside. The site is a former farm, which consists of a traditional farmhouse and a range of traditional brick barns (including part Dutch Barn) and more modern farm buildings. The nearest neighbouring property (The Old Vicarage) is located 130 metres to the north of the site. The site currently has two vehicular access points and there are a number of large trees to the front of the site. Part of the site is located within the Flood Zone as identified by the Environment Agency DETAILS OF PROPOSAL This proposed development is for the conversion of the range of traditional barns into 9 dwellings and the subdivision of the existing farmhouse into 2 dwellings. -

BP the Combermere Arms and Burleydam

Uif!Dpncfsnfsf!Bsnt!jt!b!dmbttjd! Diftijsf!dpvnusz!jnn!xjui!qmfnuz!pg!npplt! Uif!Dpncfsnfsf!Bsnt! bne!dsbnnjft!bne!mput!pg!dibsbdufs/ bne!Cvsmfzebn-! A 3 mile circular pub walk from the Combermere Arms in Burleydam, Cheshire. The walking route performs a simple loop through the surrounding countryside, taking in the Wijudivsdi-!Diftijsf peaceful setting of the farming landscape. Hfuujnh!uifsf Moderate Terrain Burleydam is located on the A525 to the east of Whitchurch, close to the Cheshire/Shropshire border. The walk starts and finishes from the Combermere Arms which has its own large car park alongside. Approximate post code SY13 4AT. 4!njmft! Djsdvmbs!!!! Wbml!Tfdujpnt 2/6!ipvst Go 1 Tubsu!up!Dbuumf!Hsje To begin the walk, walk along the pub car park away from the 060614 pub to reach the hedge at the bottom. On the right you’ll see a metal gate out to the road with a footpath sign, do NOT go through this instead turn left to join the grass footpath between hedges, passing the pub’s LPG cylinders on the left. Go through the next metal gate into a field. Keep straight ahead on the path, running along the right-hand Access Notes edge of this crop field. Pass through the metal gate and go over the old wooden bridge into the next field. Again, keep straight ahead for some distance along the right-hand 1. The walk has just a few gentle climbs and boundary of this large crop field. Along the way you’ll pass a descents throughout. few redundant and overgrown gates set alongside the hedge. -

Freewhitchurch Cycle Rides

& Follow the road to a T-junction and turn right towards Route 4 © Crown copyright and database rights Route 3: To Malpas and Threapwood Eglwys Cross Short Cut 2014 Ordnance Survey 100049049 Further information 2 NATIONAL CYCL E Total distance: 22½ miles in total (35 km in total) To take the short cut, avoiding Audlem, turn ROUTE 45 ( Turn first left, signposted to Whitewell left in Ightfield signposted to Burleydam 18 Shropshire Un Tourist information This route includes some cycling along main roads and some Wrenbury 17 Whitchurch Tourist Information Centre: 01948 664577 steep hills and is therefore suitable for more experienced ) When the road splits, bear right past a small green towards Wrexham. 2a Go through Burleydam and at the next Aston Shrewsbury Tourist Information Centre: 01743 258888 cyclists. After leaving Whitchurch along the canal towpath, At the T-junction, turn right on to the A525 (take care) T-junction turn right signposted to Wilkesley A525 i Stear on Cana Nantwich Tourist Information Centre: 01270 628633 Bridge 16 you will encounter a famous set of locks at Grindley Brook. * b Pinsley Turn first left onto Bowker’s Lane, signposted to Fenns Bank 2 After ½ mile turn first left (unsigned) Green The Grange The route then heads into the rolling countryside of Cheshire; FREE Marley 19 l Whitchurch + Go straight over at the next crossroads, signposted to Fenns Bank (take care) c Marbury Cycle Shops refreshments can be found in the picturesque village of Malpas. 2 At the crossroads with the A525 go straight Green Hollin Green Wheelbase: 21 Watergate Street, Whitchurch. -

Appeal Decision

Appeal Decision Site visit made on 17 December 2012 by Mr A Thickett BA(Hons) BTP MRTPI Dip RSA an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Decision date: 23 January 2013 Appeal Ref: APP/R0660/A/12/2179033 Land off Sheppenhall Lane, Aston, Cheshire, CW5 8DE • The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant planning permission. • The appeal is made by Newlyn Homes Ltd against the decision of Cheshire East Council. • The application Ref 11/2818N, dated 27 July 2011, was refused by notice dated 12 April 2012. • The development proposed is the erection of 43 dwelling houses (including 5 affordable houses) and creation of new access to Sheppenhall Lane. Decision 1. The appeal is allowed and planning permission granted subject to the conditions set out in Schedule 1 at the end of this decision. Main Issue 2. The appeal site comprises part of a field on the southern edge of Aston. Aston is a small village in the open countryside. The appellant accepts that the proposed development conflicts with Policy NE.2 of the Borough of Crewe and Nantwich Replacement Local Plan 2011 which exercises strict control over development in the open countryside. The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) resists isolated new housing in the countryside unless, amongst other things, it constitutes appropriate enabling development to secure the future of heritage assets. 3. The appellant argues that the conflict with the Policy NE.2 is outweighed by the planned use of the funds raised by the proposed development to aid the restoration of Combermere Abbey. -

Committee for Ministry Meeting 29 September 2015

Notes from CFM Committee for Ministry Meeting 19:30 Tuesday, 29 September 2015 ‘Congo’ Church House, Daresbury, Warrington WA4 4GE Apologies: Isobel Burney, Mike Gilbertson, Andrew Lythall, Ian Parkinson, Paul Smith In Attendance: Ruth Ackroyd, Ann Barlow, David Blackmore, David Felix, James Hughes, Joe Kennedy, Julie Withers. Also in attendance: Christopher Burkett (DofM) and Jane Hood (Minute Secretary) 1.0 Opening worship led by Christopher Burkett. 2.0 Apologies as above. 3.0 Notes from previous meeting held 23 April 2015: no comments. 4.0 Matters arising (not dealt with elsewhere): 5.1 RME continues with the next round of discussions in October. CfM staff will be attending meetings on 14 and 21 October. The recommendations which were accepted by Archbishops’ Council and the House of Bishops were sent to Christopher Burkett today. Many of the revolutionary ideas in the original proposals have now been abandoned. Vote 1 and pooling of resources will continue and the training grant will be age-weighted. Fees will be pro rata. ASCMM needs to know what its income will be to fund expenditure. David Felix will be attending consultation in November. 5.3 Annual conference. Elaine Graham has accepted invitation and will speak on discipleship. Ketso – a tool for creative engagement – will be used. Ann Barlow organising this. Newly elected CfM members will be invited to the conference. 7.0 Social evening. This is a good opportunity for fellowship without an agenda; ideas for next year’s event welcomed. 5.0 Staff appointments 5.1 Twelve Pastoral Workers were admitted and licensed by Bishop Libby on 26 September. -

Warburton Trees Index

Last Name First & Mid Name Birth Date Christening Date Death Date Birth Place Flags Adele Luise 14 Jul 1883 30 Jun 1958 Hale Barns Agnes Arley Clan Alice Arley Clan Alice aft 1651 Edenfield Clan Alice Warburton Village Alice 1650 Hale Barns Alice Booth abt 1866 Poynton, Cheshire Poynton clan Alla Garryhinch Clan Ann Edenfield Clan Ann 1846 Warburton Village Ann Hamlets Clan Ann abt 1830 Shocklach, Cheshire Shocklach Clan Ann Turton Clans Ann abt 1790 15 Mar 1836 Turton Clans Ann abt 1820 Ireland Warburton Village Ann abt 1856 Manchester, Lancashire Warburton Village Ann Families, Percy Gray Family Ann Hale Barns Anne 1697 23 Apr 1750 Edenfield Clan Annie abt 1877 Buckley, Flintshire Shocklach Clan Audrey Sandbach Clan Barbara Edenfield Clan Betty 1746 19 Sep 1821 Edenfield Clan Betty Hamlets Clan Betty abt 1789 9 Jun 1817 Turton Clans Betty Cardiff Family, Families 2 Catherine abt 1751 16 Mar 1826 Pennsylvania Clan Clara 13 Jul 1854 25 Oct 1927 Pennsylvania Clan Clara B 14 May 1875 Pennsylvania Pennsylvania Clan Deborah 1780 Haslingden Clan Douglas Bolton (The Bakers) Clan Eliza Bancrofts Clan Eliza Ann abt 1826 Ohio Pennsylvania Clan Elizabeth Pool Bank Clan Elizabeth abt 1813 1877 Hattersley, Cheshire Pool Bank Clan Elizabeth abt 1848 Dorrington, Lincolnshire Mobberley Elizabeth Tottington Clan Ellen aft 1355 Arley Clan Ellen abt 1759 Hamlets Clan Ellen Turton Clans Ellen abt 1854 Frodesley, Shropshire Houghton Clan Ellen 1861 Staleybridge, Lancashire Hale Barns Estella abt 1853 Massachusetts Pennsylvania Clan Florence Hale Barns Frances -

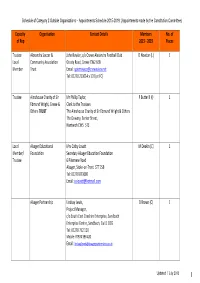

Appointments to Outside Organsations

Schedule of Category 2 Outside Organisations – Appointments Schedule 2015-2019: (Appointments made by the Constitution Committee) Capacity Organisation Contact Details Members No. of of Rep 2015 - 2019 Places Trustee Alexandra Soccer & John Bowler, c/o Crewe Alexandra Football Club D Newton (L) 1 Local Community Association Gresty Road, Crewe CW2 6EB Member Trust Email: [email protected] Tel: 01270 213014 x 110 (at FC) Trustee Almshouse Charity of Sir Mr Phillip Taylor, P Butterill (I) 1 Edmund Wright, Crewe & Clerk to the Trustees Others TRUST The Almshouse Charity of Sir Edmund Wright & Others The Dowery, Barker Street, Nantwich CW5 5TE Local Alsager Educational Mrs Cathy Lovatt M Deakin (C) 1 Member/ Foundation Secretary Alsager Education Foundation Trustee 6 Pikemere Road Alsager, Stoke-on-Trent ST7 2SB Tel: 01270 873680 Email: [email protected] Alsager Partnership Lindsay Lewis, D Brown (C) 1 Project Manager, c/o South East Cheshire Enterprise, Sandbach Enterprise Centre, Sandbach, Cw11 1DG Tel: 01270 752 120 Mobile: 07974 398 420 Email: [email protected] Updated: 7 July 2015 1 Schedule of Category 2 Outside Organisations – Appointments Schedule 2015-2019: (Appointments made by the Constitution Committee) Capacity Organisation Contact Details Members No. of of Rep 2015 - 2019 Places APSE – Association for Public Mo Baines D Marren (C) 2 Service Excellence Principal Advisor P Findlow (C) Association for Public Service Excellence 2nd Floor, Washbrook House Lancastrian Office Centre Talbot Road, Old Trafford -

6 Lower Farm Barns, Burleydam SY13 4AT

6 Lower Farm Barns, Burleydam SY13 4AT A highly individual and superbly designed barn conversion of the highest calibre on an exceptional select courtyard setting in delightful countryside and surroundings affording outstanding features and stylish qualities whilst incorporating many Period details Vaulted galleried reception hall, large luxurious open plan living family dining kitchen, lounge, two ground floor bedrooms, one ground floor en suite, cloakroom and laundry room. Two first floor principal bedroom suites with en suite and walk in wardrobes. Standing in a corner position with lovely rural aspects, large gardens and two garages. No chain for early completion. • A impeccably appointed and superbly styled barn conversion of immense appeal • Standing in the corner of a small select courtyard location • Situated within delightful surroundings in highly sought after countryside nearby to Nantwich • Lovely contemporary styling throughout whilst affording many original character features • Stunning galleried and vaulted reception hall, large fully appointed kitchen/dining and living area • Separate lounge with fireplace and log burner, cloakroom, laundry room • Two ground floor double bedrooms, one ground floor en suite • Two first floor principal bedroom suites with en suite bathroom, en suite shower room and walk in wardrobes • Extensive gardens to the South and West bordering open fields, two garages • No chain for early completion Agents Remarks No 6. is one of a small select number of exclusive barn conversions around a courtyard setting within the quaint village of Burleydam and nearby to Audlem, Aston and close to the historic market towns of Whitchurch and Nantwich. A path leads from the courtyard to the renowned Pub and Restaurant "The Combermere Arms". -

Cheshire (Vice County 58) Moth Report for 2016

CHESHIRE (VICE COUNTY 58) MOTH REPORT FOR 2016 Oleander Hawk-Moth: Les Hall Authors: Steve H. Hind and Steve W. Holmes Date: May 2016 Cheshire moth report 2016 Introduction This was the final year of recording for the National Macro-moth Atlas. A few species were added to squares during daytime searches early in the year but any plans to trap in under- recorded squares were often thwarted by cold nights and it was not until mid-July that SHH considered it worthwhile venturing into the uplands. The overall atlas coverage in the county has been good and our results should compare well against the rest of the country, although there remain gaps in most squares, where we failed to find species which are most likely present. Hopefully these gaps will be filled over the next few years, as recording of our Macro-moths continue. As always, a list of those species new for their respective 10km squares during 2016 can be found after the main report. A special effort was made during the winter to add historical records from the collections at Manchester Museum and past entomological journals, which will enable us to compare our current data with that of the past. Now that recording for the Macro- moth atlas is over, our efforts turn to the Micro-moths and the ongoing Micro-moth recording scheme. There is a lot to discover about the distributions of our Micro-moths across the county and the increasing interest continues to add much valuable information. 2016 was another poor year for moths, with results from the national Garden Moth Scheme showing a 20% decline on 2015 (excluding Diamond-back Moth, of which there was a significant invasion). -

POA GGT Cheshire

CHESHIRE HISTORY FALCONRY CULTURE explore. eat. drink. stay. DAILY ITINERARY DAY ONE Arrival Dorothy Clive Garden Cholmondeley Castle 1 Standard Room in a 4 star hotel including Dinner, Bed & Breakfast* DAY TWO Cheshire Falconry Bluebell Cottage and Nurseries Combermere Abbey 1 Standard Room in a 4 star hotel including Dinner, Bed & Breakfast* DAY THREE Tatton Park Arley Hall and Gardens Norton Priory Museum and Gardens Departure DAY ONE Welcome to Cheshire - The Shire of the City of Legions! This morning take delight in exploring surprises and delights of the Dorothy Clive with 12 acres of garden including a new winter garden, edible woodland, woodland quarry with waterfall, alpine scree with pool, rose walk and an amazing seasonal border. The garden has notable plant collections including: rhododendrons, azaleas, camellias, sarcococca and hydrangeas. You will enjoy taking in the garden themes then end with a refreshment break or lunch at the delightful Dorothy Clive Tearoom with a wonderful outdoor terrace. The afternoon will be enjoying the exquisite and peaceful surroundings of Cholmondeley Castle Gardens, the Cholmondeley family have lived on the lands since Norman times with the castle being built in the early 19th Century by the first Marquess. Take delight in exploring 70 acres of gardens including the Romantic Temple, Folly Water Gardens, Rose Garden, Glade, Arboretum, ornamental woodlands and the newLavinia Walk, a 100m long double herbaceous border dedicated to the legacy of the late Lady Lavinia Cholmondeley. DAY TWO Today the morning will start with an opportunity to get close to nature with a chance to fly magnificent birds of prey at Cheshire Falconry as you will enjoy a one to one meet the birds experience.