Knowledge on the Run. Uncertainties in the Careers of Kenyan Long-Distance Runners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

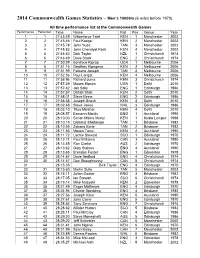

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

World Record Holders and Olympic Medalists at the Sportisimo Prague Half Marathon

PRESS RELEASE 1 March 2017 World Record Holders and Olympic Medalists at the Sportisimo Prague Half Marathon Today the RunCzech Organisation announced a World-Class field including two World Record Holders; Peres Jepchirchir and Leonard Patrick Komon, and two Rio Olympic Medalists; Galen Rupp and Tamirat Tola who will compete on April 1st in the 2017 edition of the Sportisimo Prague Half Marathon. The women’s list features the reigning World Champion, Peres Jepchirchir fresh from her Half marathon World Record performance (1:05:06 in RAK) in February. She will be challenged by the Prague event record holder Violah Jepchumba (1:05:51) who ran the fastest half marathon in the world in 2016, and RunCzech Racing’s young star, Joyciline Jepkosgei (1:06:08 in RAK this year). The race will include two other women with PRs under 1:07; Worknesh Degefa of Ethiopia, the former event record holder and Kenyan Gladys Chesir. Of interest also are two American challengers Jordan Hasay who debuted in Houston this year with a 1:08:40 and Maegan Krifchin (1:09:51) along with the fastest Czech woman, Eva Vrabcova. The men’s field is also blessed with a World Record Holder in the person of Leonard Patrick Komon who claims road records at 10K and 15K which he set in 2010. Komon will be trying to improve on his third place finish in Prague from 2015. The biggest threat may come from another Kenyan, Barselius Kipyego who ran 59:15 in Usti nad Labem last September setting a course record on what had not previously been considered a fast course. -

RESULTS Mixed Relay

REVISED Kampala (UGA) World Cross Country Championships 26 March 2017 RESULTS Mixed Relay UGANDA DISQUALIFIED 26 March 2017 14:00 START TIME 26° C 65 % TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY 14:38 END TIME 26° C 65 % PLACE TEAM BIB RESULT 1 KENYA KEN 5 22:22 Asbel KIPROP (M) 5:19 (1) Winfred Nzisa MBITHE (W) 6:07 (2) 11:26 (1) Bernard Kipkorir KOROS (M) 4:58 (1) 16:24 (1) Beatrice CHEPKOECH (W) 5:58 (7) 2 ETHIOPIA ETH 3 22:30 Welde TUFA (M) 5:25 (2) Bone CHELUKE (W) 6:16 (4) 11:41 (2) Yomif KEJELCHA (M) 5:22 (2) 17:03 (2) Genzebe DIBABA (W) 5:27 (2) 3 TURKEY TUR 11 22:37 Aras KAYA (M) 5:31 (2) Meryem AKDAG (W) 6:13 (2) 11:44 (3) Ali KAYA (M) 5:24 (2) 17:08 (3) Yasemin CAN (W) 5:29 (2) 4 BAHRAIN BRN 1 23:20 Sadik MIKHOU (M) 5:36 (3) Dalila ABDULKADIR (W) 6:11 (3) 11:47 (4) Benson Kiplagat SEUREI (M) 5:35 (3) 17:22 (5) Tigist GASHAW (W) 5:58 (7) 5 MOROCCO MAR 6 24:02 Mohamed TINDOUFT (M) 5:39 (4) Oumaima SAOUD (W) 6:39 (7) 12:18 (6) Sanae EL OTMANI (W) 6:12 (5) 18:30 (7) Brahim KAAZOUZI (M) 5:32 (3) 6 UNITED STATES USA 13 24:08 Cory LESLIE (M) 5:44 (3) Eleanor FULTON (W) 6:46 (3) 12:30 (9) Marisa HOWARD (W) 6:42 (3) 19:12 (9) Paul Kipkemoi CHELIMO (M) 4:56 (3) 7 TANZANIA TAN 10 24:13 Faraja Damas LAZARO (M) 5:39 (3) Sicilia Ginoka PANGA (W) 6:48 (3) 12:27 (7) Jackline SAKILU (W) 6:32 (3) 18:59 (8) Marco Silvester MONKO (M) 5:14 (3) 8 SPAIN ESP 8 24:29 Marc ALCALÁ (M) 6:11 (7) Solange PEREIRA (W) 6:27 (5) 12:38 (10) Jesús RAMOS (M) 5:47 (4) 18:25 (6) Blanca FERNÁNDEZ (W) 6:04 (9) 9 ERITREA ERI 2 24:47 Netsanet NEGASI (W) 6:51 (8) Berhane TESFAY (M) 5:50 (1) -

Pruebas Del Calendario Nacional 2015/2016

PruebasPruebas deldel calendariocalendario nacionalnacional Fecha Prueba HOMBRES MUJERES 8 noviembre Torredonjimeno Diego Merlo Esther Hidalgo 14 noviembre Atapuerca Imane Merga (ETH) Belaynesh Oljira (ETH) 22 noviembre Soria Timothy Toroitich (UGA) Linet Masai (KEN) 22 noviembre Toledo Roberto Alaiz Alessandra Aguilar 29 noviembre Alcobendas Tamirat Tola (ETH) Linet Masai (KEN) 29 noviembre Burlada Abdelaziz Merzougui Paula González 5 diciembre Aranda de Duero Aron Kifle (ERI) Olivia Mugove Chitate (ZIM) 6 diciembre Granollers Carles Castillejo Vitaline Jemaiyo Kibii (KEN) 8 diciembre Cantimpalos Moses Kibet (UGA) Olivia Mugove Chitate (ZIM) 13 diciembre Quintanar Berhane Amanuel (ERI) Viktoria Pogorielska (UKR) 13 diciembre Yecla Aweke Ayalew (BRN) Olivia Mugove Chitate (ZIM) 20 diciembre Venta de Baños Aweke Ayalew (BRN) Alemitu Heroye (ETH) 6 enero Amorebieta Thomas Ayeko (UGA) Mercy Cherono (KEN) 17 enero Santiponce Tamirat Tola (ETH) Faith Chepngetich Kipyegon (KEN) 24 enero Elgoibar Aweke Ayalew (BRN) Irene Chepet Cheptai (KEN) 24 enero Huesca Goitom Kifle (ERI) Raquel Miró 31 enero San Sebastián Imane Merga (ETH) Hiwot Ayalew (ETH) 31 febrero Madrid José España Rehima Serro 7 febrero Valladolid Ayad Lamdassem Alessandra Aguilar 14 febrero Valencia de Alcántara Philip Kipyego (UGA) Hiwot Ayalew (ETH) 14 febrero Sonseca Sergio Sánchez Lucía Morales 649 PRUEBAS DEL CALENDARIO NACIONAL 2015/2016 XXX CROSS DEL ACEITE HISTORIAL DE VENCEDORES Torredonjimeno (Jaén), 8 de noviembre Año HOMBRES MUJERES HOMBRES 1985 Juan José Rosario Laura Blanco Senior/Promesa (9.000m): 1. Diego Merlo 36:37 - 2. Mohamed Lansi 1986 Juan José Rosario Marina Gutiérrez 36:57 - 3. Cristobal Valenzuela 37:04 - 4. Pablo Sánchez 37:08 - 5. 1987 Manuel Chamorro María Carmen Liébana Rubén Alvarez 37:17 1988 Manuel Pancorbo Carmen Mingorance Promesa (9.000m): 1. -

Marathon Freak Out

SURVIVING THE MARATHON FREAK OUT A Guide to Running Your Best Marathon GREG McMILLAN, M.S. Surviving the Marathon Freak Out Get the Latest and Greatest! With the purchase of this book, you now have another person (me) on your support team as you head into your marathon. I’m very much looking forward to working with you for the best marathon of your life. In order to help you get the most out of this Guide, step one is to “register” your book, which sounds more glamorous than it is. Just send an email to [email protected] to let me know you have the book. I can then keep you updated as I add to the book and have more tips and advice to share. Simple as that. © Greg McMillan, McMillan Running LLC | www.McMillanRunning.com 1 Surviving the Marathon Freak Out My Promise Don’t worry. It’s going to be okay. I promise. I know you’ve been training for the big day (a.k.a. marathon day) for a while now so it’s normal to get anxious as the day approaches. I’ve been there too. As a runner, I’ve dealt with the rigors of marathon training and the nervousness as the race nears, none more so than before my first marathon, the New York City Marathon or before I won the National Masters Trail Marathon Championships a few years ago. As a coach, I’ve trained thousands of runners just like you for marathons around the globe, in every weather condition and over all types of crazy terrain. -

Final START LIST 5000 Metres MEN Loppukilpailu

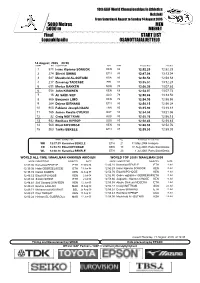

10th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki From Saturday 6 August to Sunday 14 August 2005 5000 Metres MEN 5000 m MIEHET ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHL Final START LIST Loppukilpailu OSANOTTAJALUETTELO ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETI 14 August 2005 20:20 START BIB COMPETITOR NAT YEAR Personal Best 2005 Best 1 571 Isaac Kiprono SONGOK KEN 84 12:52.29 12:52.29 2 274 Sileshi SIHINE ETH 83 12:47.04 13:13.04 3 587 Moukheld AL-OUTAIBI KSA 80 12:58.58 12:58.58 4 217 Zersenay TADESSE ERI 82 13:05.57 13:12.23 5 691 Marius BAKKEN NOR 78 13:06.39 13:07.63 6 558 John KIBOWEN KEN 69 12:54.07 13:07.74 7 15 Ali SAÏDI-SIEF ALG 78 12:50.86 13:13.50 8 565 Benjamin LIMO KEN 74 12:54.99 12:58.66 9 264 Dejene BIRHANU ETH 80 12:54.15 12:56.24 10 905 Fabiano Joseph NAASI TAN 85 13:15.90 13:18.18 11 765 James Kwalia C'KURUI QAT 84 12:54.58 13:21.36 12 32 Craig MOTTRAM AUS 80 12:55.76 12:56.13 13 932 Boniface KIPROP UGA 85 12:58.43 12:58.43 14 560 Eliud KIPCHOGE KEN 84 12:46.53 12:52.76 15 263 Tariku BEKELE ETH 87 12:59.03 12:59.03 MARK COMPETITOR NAT AGE Record Date Record Venue WR12:37.35 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH 2131 May 2004 Hengelo CR12:52.79 Eliud KIPCHOGE KEN 1831 Aug 2003 Paris Saint-Denis -

Landesrekorde Marathon Welt

Landesrekorde Stand: 20.12.2020 Landesrekorde Marathon der Männer Landesrekorde Marathon der Frauen Pl. Land Zeit Diff. Name Jahr Ort Pl. Land Zeit Diff. Name Jahr Ort 1. Kenia 2:01:39 Eliud Kipchoge 2018 Berlin 1. Kenia 2:14:04 Brigid Kosgei 2019 Chicago 2. Äthiopien 2:01:41 (0:00:02) Kenenisa Bekele 2019 Berlin 2. Großbritanien 2:15:25 (0:01:21) Paula Radcliffe 2003 London 3. Türkei 2:04:16 (0:02:37) Kaan Kigen Özbilen 2019 Valencia 3. Äthiopien 2:17:41 (0:03:37) Degefa Workneh 2019 Dubai 4. Bahrain 2:04:43 (0:03:04) El Hassan el-Abbassi 2018 Valencia 4. Israel 2:17:45 (0:03:41) Lonah Chematai Salpeter 2020 Tokio 5. Belgien 2:04:49 (0:03:10) Bashir Abdi 2020 Tokio 5. Japan 2:19:12 (0:05:08) Mizuki Noguchi 2005 Berlin 6. England 2:05:11 (0:03:32) Mo Farah 2018 Chicago 6. Deutschland 2:19:19 (0:05:15) Irina Mikitenko 2008 Berlin 7. Großbritanien 2:05:11 (0:03:32) Mo Farah 2018 Chicago 7. USA 2:19:36 (0:05:32) Deena Kastor 2006 London 8. Uganda 2:05:12 (0:03:33) Felix Chemonges 2019 Toronto 8. China 2:19:39 (0:05:35) Yingjie Sun 2003 Beijing 9. Marokko 2:05:26 (0:03:47) El Mahjoub Dazza 2018 Valencia 9. Namibia 2:19:52 (0:05:48) Helalia Johannes 2020 Valencia 10. Japan 2:05:29 (0:03:50) Suguru Osako 2020 Tokio 10. Rußland 2:20:47 (0:06:43) Galina Bogomolova 2006 Chicago 11. -

How Eliud Kipchoge's Unique Physiology Attenuates His

Flattening the curve: how Eliud Kipchoge’s unique physiology attenuates his age- related performance decline Hunter L. Paris1, Chad C. Wiggins2, Ren-Jay Shei3 1Department of Sports Medicine, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA 2Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA 3Independent Sport Scientist, Carlsbad, CA, USA Address for correspondence: Hunter L. Paris, Ph.D. Department of Sports Medicine Pepperdine University Malibu, CA 90263 E-mail: [email protected] Word Count (excluding Abstract, References, and Figure Legends): 1234 Abstract Word Count: 90 1 Abstract The aim of this study was to examine the physiological profile of Eliud Kipchoge in his attempt at a master’s M50 (age 50-54) marathon World Record. Additionally, by comparing Kipchoge’s physiology over the past two decades with those of healthy individuals, we document his age-related decline in performance, thereby demonstrating the extreme limit of what is understood to be physiologically plausible. Coupled with his eclipsing of the World Record, Kipchoge’s data demonstrate that although aging remains inevitable, technological advancements and world class physiology slow age-related decrements in health and performance. 2 Introduction Following the cancelation of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics due to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), the world gasped when Eliud Kipchoge (EK) retired from athletics, pursuing instead his career in men’s fashion (sparked by his experience with GQ magazine). Though EK continued to run recreationally and annually contributed physiological data towards a longitudinal study on aging, twenty years strode silently by before Kipchoge once again donned a bib number and race kit. In 2039, the much anticipated return of, “the philosopher” arrived. -

The Things Runners Have Built

The Things Runners Have Built Jackie Lebo takes us to Eldoret, Kenya where development is taking place thanks to the investment of earnings of Kenyan runners. On this hot Saturday in early June, it seems half of Eldoret has come to shop for groceries at Tusker Mattresses Supermarket. The parking lot across the road is full. People come out, from whole families laden with paper bags branded with the supermarket logo to lone women balancing bags on their heads braving the blistering sun on their long walk home. Tusker Mattresses Supermarket is located on two floors of the five-story Komora Centre, a large building in the middle of town that covers almost an entire city block. It is owned by Moses Kiptanui, the runner who dominated the 3000 m steeplechase races for about five years in the nineties. Kiptanui broke world records, won awards, and the only thing that eluded him was the Olympic gold, which he lost by a razor thin margin to fellow Kenyan Joseph Keter in the 1996 Atlanta games. The steeplechase is special. Even more than other middle and long distance races that have brought Kenyans fame, Kenyan steeplechasers have won all eight times they entered during the last ten Olympics. In 1976 and 1980 Kenya boycotted the Olympics. It is fitting that Kiptanui, one of Kenya’s most successful athletes, is now one of the largest athlete-investors in Eldoret. Eldoret is experiencing a property boom, with growth rates of almost 8%, three times the national average. The changing skyline shows the continuing investment of runners in commercial real estate. -

Marathon Issue • NZ Marathon Guide • How to Optimise Marathon Pacing • Tackling the Long Run Road Relay in Review Top Club Again Folks! Life Membership: Grant Mclean

DECEMBER 2012 Issue 13 THE marathon ISSUE • NZ marathon guide • How to optimise marathon pacing • Tackling the Long Run ROAD RELAY IN REVIEW Top Club again folks! LIFE MEMBERSHIP: Grant McLean The B-Boyz: a social history Unravelling the B’s culture Day at the races: Tim Hodge reports on success in Chiba 1 WE WOULD LIKE YOUR THOUGHTS ABOUT WHAT THE CLUB PROVIDES, WHAT YOU LIKE, WHAT WE CAN DO BETTER, WHAT ELSE WE COULD OFFER AND SO ON... WATCH OUT FOR THE GREAT SCOTTISH SURVEY IN LATE JANUARY. THE SURVEY WILL BE AVAILABLE ONLINE AND IN HARDCOPY 2 Contents From the Features: Editor Life Member: Grant McLean 5 Todd Stevens Well, I never thought I New Zealand marathon review 7 would end up on the cover Michael Wray of a running magazine. It Marathon pacing strategies 13 wasn’t my goal in taking Michael Wray on the editor’s job – I promise! I have been The Short Guide to the Long Run 15 Matt Dravitzki incredibly humbled by being awarded the honour Back on home soil 19 Dan Wallis of life membership by this special club – thank you A summer running in London 21 club mates and special Hayden Shearman thanks to Todd, my great Columns: friend, for all his support in Managing diabetes on the run my Scottish career. I hope I Edwin Massey 26 can continue to serve you all long into the future. Team Updates 29 Just before we take a well-deserved Christmas/New Year Day at the Races: rest, we reflect on another amazing year for the club and Chiba Ekiden Relay, Japan 34 start to eye up some goals for 2013. -

Editorial Style from a to Z April 2012

Contents A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z London 2012 Editorial style from A to Z April 2012 The aim of this editorial style guide is to If you are giving this guide to anyone Introduction help everyone write about London 2012 externally, please inform LOCOG’s with clarity and consistency. The guide Editorial Services team or the ODA’s includes practical information to ensure Marketing team so we can let them writers prepare accurate content in the know when it is reissued. If you have most suitable style. any queries that are not covered by the guide, please let us know so we The guide is arranged alphabetically for can include them in future editions. ease of use, with simple navigational tools to help you find what you’re looking Working together, we will develop for. Clicking on the letters across the top effective and accessible content that of every page will take you to the first will help make London 2012 an page of each section. In addition, each incredible experience for all audiences. entry on the contents page is a link, and there are cross-references with links to other sections throughout the guide. As our organisation develops, so our style guide needs to be flexible and adaptable. For this reason, we will be regularly updating this document. Please ensure that you have the latest version. This document and the official Emblems of the London 2012 Games are © London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Limited 2007–2012. -

Farah Finishes Third As Kipchoge Wins

SPORTS Monday, April 23, 2018 21 Marquez explains London Marathon Vinales impeding Austin was preoccupied with Iannone eigning MotoGP champion riding slow up ahead. Marc Marquez says the “Unluckily, I was going out Farah finishes third blockR on Maverick Vinales that of the box, I expected that cost him pole for the Austin nobody was coming behind and race happened because he was suddenly I heard an engine,” focused on keeping Andrea Marquez recalled. Iannone ahead. “I was looking more for Vinales was on a quick lap Iannone than who was coming Londonas Kipchoge wins and set to challenge Marquez’s behind, and when I heard ritain’s Mo Farah finished provisional pole benchmark the engine I go in as quick third at the London when he came up on the Honda as possible - but looks like I MarathonB in a new British rider in the final sector and was disturbed the lap.” record as Kenyan Eliud forced to back out, gesticulating Marquez explained that Kipchoge won the race for a angrily at Marquez as he rode he was concerned about third time. past. having Iannone follow him Farah kept pace with the He recovered with his next on his flying lap, given the leaders for much of the race lap, finishing four tenths off Suzuki rider had been quick but was two minutes and four Marquez in second, before a throughout the weekend. seconds behind Kipchoge. three-place penalty for the latter “Here normally I don’t need He crossed the line in two promoted the Yamaha man to slipstream but I know that hours, six minutes and 21 first place on the grid.