Opera for the Domestic Apocalypse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

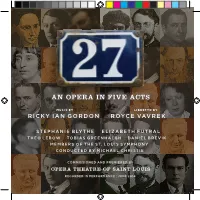

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B. -

20171017 Icco.Pdf (254.66

Ithaca College Chamber Orchestra Octavio Más-Arocas, conductor Ford Hall Tuesday, October 17th, 2017 8:15 pm Program Opening for a New Year (2018) Nick O'Brien ’18 (b. 1996) World Premiere, IC Orchestras Fanfare Project haunted topography (version for sinfonietta) David T. Little (b. 1978) Symphony No. 7 in A Major, op. 92 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827) Poco sostenuto - Vivace Allegretto Presto Allegro con brio Ithaca College Chamber Orchestra Violin I Flute Alem Ballard Jeannette Lewis Kathryn Drake Hannah Morris * Reuben Foley Nicole Murray ^ Kai Hedin Daniel McCaffrey Oboe Peter Nowak Melissa DeMarinis Emily Scicchitano Ellen O'Neill * ^ Henry Scott Smith Esther Witherell * Clarinet Erin Dowler * Violin II Emma Grey Bailey Angstadt Darya Barna Bassoon Emilie Benigno Olivia Fletcher * Shelby Dems * Brittany Giles ^ Lily Mell Taylor Payne Horn Kristina Sharra Jacob Factor * Gabriella Stout Nicoletta Pignatello ^ Jeremy Strauss Viola Alyssa Budzynski Trumpet Zac Cohen Peter Gehres Richard Cruz Michael Stern ^ Carter Kohler Kristen Warnokoski * Karly Masters Michelle Metty Trombone Jacob Shur * Will Esterling ^ Cello Piano Molly DeLorenzo * Manuel Gimferrer Mechu Lippert Craig Mehler Timpani Aidan Saltin Grace Asuncion Hideo Schwartz David Shane Percussion Benjamin Brown-McMillin Bass Dan Syvret * Katelyn Adams Kiefer Fuller * * = Principal for Beethoven Tristen Jarvis ^ = Principal for Little Ryan Petriello Biographies David T. Little David T. Little is “one of the most imaginative young composers” on the scene, a “young radical” (The New Yorker), with “a knack for overturning musical conventions” (The New York Times). His operas JFK (Royce Vavrek, librettist; Fort Worth Opera / Opéra de Montréal / American Lyric Theater), Dog Days (Royce Vavrek, librettist; Peak Performances / Beth Morrison Projects), and Soldier Songs (Prototype Festival) have been widely acclaimed, “prov[ing] beyond any doubt that opera has both a relevant present and a bright future” (The New York Times). -

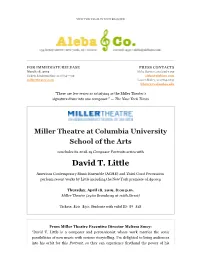

Miller Theatre Presents a Composer Portrait of David T. Little, 4/18

VIEW THIS EMAIL IN YOUR BROWSER FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACTS March 18, 2019 Aleba Gartner, 212/206-1450 Tickets & Information: 212/854-7799 [email protected] millertheatre.com Lauren Bailey, 212/854-1633 [email protected] "There are few series as satisfying as the Miller Theater’s signature dives into one composer." — The New York Times Miller Theatre at Columbia University School of the Arts concludes its 2018-19 Composer Portraits series with David T. Little American Contemporary Music Ensemble (ACME) and Third Coast Percussion perform recent works by Little including the New York premiere of Agency Thursday, April 18, 2019, 8:00 p.m. Miller Theatre (2960 Broadway at 116th Street) Tickets: $20–$30; Students with valid ID: $7–$18 From Miller Theatre Executive Director Melissa Smey: “David T. Little is a composer and percussionist whose work marries the sonic possibilities of new music with serious storytelling. I’m delighted to bring audiences into his orbit for this Portrait, so they can experience firsthand the power of his dramatic and emotionally compelling compositions.” Q&A with Melissa Smey about this Portrait by writer Lara Pellegrinelli https://www.millertheatre.com/about/news/david-t-little-QA David T. Little (photo by Matt Zugale for Miller Theatre) Composer Portraits Thursday, April 18, 2019, 8:00 p.m. Miller Theatre (2960 Broadway at 116th Street) David T. Little David T. Little grapples with essential human issues through powerfully dramatic compositions. This Portrait features two major works—companion pieces presented together for the first time—that explore the tension between the individual, secrecy, and state violence. -

Analyzing Gender Inequality in Contemporary Opera

ANALYZING GENDER INEQUALITY IN CONTEMPORARY OPERA Hillary LaBonte A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: Jane Schoonmaker Rodgers, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Graduate Faculty Representative Kevin Bylsma Ryan Ebright Emily Pence Brown © 2019 Hillary LaBonte All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jane Schoonmaker Rodgers, Advisor Gender inequality is pervasive in the world of performing arts. There are far more female dancers, actresses, and singers than there are male performers. This inequality is amplified by fewer numbers of roles for women. This document examines gender inequality in contemporary North American operas, including the various factors that can influence the gender balance of a cast, with focused studies on commissioning organizations and ten works that feature predominantly female casts. Chapter 1 presents the analysis of all operas in OPERA America’s North American Works database written and premiered from 1995 to the present. Of the 4,216 roles in this data, 1,842 (43.6%) are for female singers. Operas written by a female composer or librettist have 48% roles for female singers, operas with a female lead character have 51%, and intentionally feminist or female-focused operas have 53% roles for female singers. Chapter 2 considers ten companies devoted to the creation and production of contemporary opera in North America. Works premiered by these companies have an average of 47% roles for women, and companies with a female executive or founder are more likely to have a higher average. Companies that use language like “innovative” or “adventurous” in their mission statement are more likely to have greater female representation in the casts of their commissioned works. -

Mirror Mirror" from the Opera, Dog Days

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School March 2020 A Performer's Guide to "No Man In His Right Mind," "Letter," and "Mirror Mirror" from the opera, Dog Days Grace Claire McCrary Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Recommended Citation McCrary, Grace Claire, "A Performer's Guide to "No Man In His Right Mind," "Letter," and "Mirror Mirror" from the opera, Dog Days" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5174. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5174 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO “NO MAN IN HIS RIGHT MIND,” “LETTER,” AND “MIRROR MIRROR” FROM THE OPERA, DOG DAYS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Grace Claire McCrary B.M., The University of Southern Mississippi, 2015 B.M.E., The University of Southern Mississippi, 2015 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2017 May 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank David T. Little and Royce Vavrek for the artistry of Dog Days. Singing and exploring the music of Lisa has inspired me immeasurably, and I am so grateful for your musical creation. -

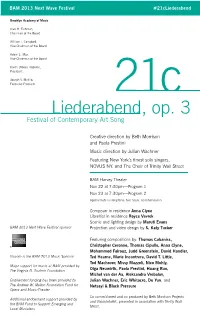

21C Liederabend , Op 3

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #21cLiederabend Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 21c Liederabend, op. 3 Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring New York’s finest solo singers, NOVUS NY, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street BAM Harvey Theater Nov 22 at 7:30pm—Program 1 Nov 23 at 7:30pm—Program 2 Approximate running time: two hours, no intermission Composer in residence Anna Clyne Librettist in residence Royce Vavrek Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Projection and video design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Endowment funding has been provided by Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, Du Yun, and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Netsayi & Black Pressure Opera and Music-Theater Co-commisioned and co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects Additional endowment support provided by and VisionIntoArt, presented in association with Trinity Wall the BAM Fund to Support Emerging and Street. Local Musicians 21c Liederabend Op. 3 Being educated in a classical conservatory, the Liederabend (literally “Song Night” and pronounced “leader-ah-bent”) was a major part of our vocal educations. -

Boris Godunov Biographies

Boris Godunov Biographies Cast Stanislav Trofimov (Boris Godunov) began his operatic career in the Chelyabinsk Opera House in 2008, and went on to perform leading bass roles at the Ekaterinburg Opera House (the Bolshoi Theatre) and other opera theaters across Russia. He became a soloist at the Mariinsky Theatre in 2016. Mr. Trofimov has portrayed numerous leading roles including Boris Godunov (Boris Godunov), Philip II (Don Carlos), Procida (I vespri siciliani), Fiesco (Simon Boccanegra), Konchak (Prince Igor), Ivan Susanin (Life of the Tsar), Sobakin (Tsar’s Bride), Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich (The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevronia), Prince Gremin (Eugene Onegin), Ferrando (Il Trovatore), Don Bartolo (Le nozze di Figaro), and Old Hebrew (Samson et Dalila). Recent performances include Procida in Mariinsky’s new production of I vespri siciliani, Zaccaria in Nabucco at the opening of Arena di Verona Summer Festival, a tour with the Bolshoi Theatre as Archbishop in The Maid of Orleans in France, and performances at the Salzburg Festival as Priest in the new production of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. Mr. Trofimov will appear at the 2018 Salzburg Festival and at Teatro alla Scala in 2019. These performances mark his San Francisco Symphony debut. This season, Cuban-American mezzo-soprano Eliza Bonet (Fyodor) made her debut at the Kennedy Center as a member of the Washington National Opera’s Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist Program, singing the role of Bradamante in Handel’s Alcina. As a part of this season’s nationwide Bernstein at 100 celebrations, Ms. Bonet performs as Paquette in Candide with the WNO, and with National Symphony Orchestra in West Side Story. -

Opera Project That Received NEA Funding

Nov 2018 Under the Freedom of Information Act, agencies are required to proactively disclose frequently requested records. Often the National Endowment for the Arts receives requests for examples of funded grant proposals for various disciplines. In response, the NEA is providing examples of the “Project Information” also called the ”narrative” for a successful Opera project that received NEA funding. The selected examples is not the entire funded grant proposal and only contain the grant narrative and selected portions. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. The following narratives have been selected as example because it represents a diversity of project type and is well written. Although the project was funded by the NEA, please note that nothing should be inferred about the ranking of each application within its respective applicant pool. We hope that you will find these records useful as an example of a well written narrative. However please keep in mind that because each project is unique, these narrative should be used as reference, rather than templates. If you are preparing your own application and have any questions, please contact the appropriate program office. You may also find additional information regarding the grant application process on our website at Apply for a Grant | NEA . Opera Opera for the Young (Opera for the Young) Beth Morrison Project (Commissioning) Utah Symphony & Opera (Repeat Productions of Newly Premiered Works) Glimmerglass Opera (Opera Festival) Patrick G. and Shirley Ryan Opera Center (Young Artist Program) Opera Omaha (World Premiere) 16-973749 Attachments-ATT20-Project_Information.pdf Opera for the Young, Inc. -

NEA Grant Search - Data As of 02-09-2021 48 Matches

NEA Grant Search - Data as of 02-09-2021 48 matches American Opera Projects, Inc. (aka AOP) 1865852-36 Brooklyn, NY 11217-1695 To support Composers and the Voice, an opera writing training program. As many as nine composers will participate in a curriculum that will include vocal writing, libretto writing, improvisation, acting for opera writers, and two public performances of their works. Fellows will write for members of the Resident Ensemble of six professional singers, one of each of the basic operatic/vocal categories: coloratura soprano, lyric soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, baritone, and bass. This cycle of the tuition-free fellowship program will introduce travel and housing subsidies intended to broaden and diversify the scope of applicants. Fiscal Year: 2021 Congressional District: 8 Grant Amount: $25,000 Category: Grants for Arts Projects Discipline: Opera Grant Period: 01/2021 - 09/2022 Atlanta Opera (aka ) 1863962-36 Atlanta, GA 30318-4235 To support a chamber opera productions of Carmen by composer Georges Bizet and Threepenny Opera by composer Kurt Weill. Performance will occur in an outdoor circus tent pitched on a baseball field with an additional two sites in Atlanta being considered. Singers for these two operas will be selected from the newly formed Company Players and Glynn Studio Players. The Company Players compruise Jamie Barton, Kevin Burdette, Jasmine Habersham, Daniela Mack, Megan Marino, Michael Mayes, Ryan McKinny, Morris Robinson, Alek Shrader, Reginald Smith, Jr., Richard Trey Smagur, and Talise Trevigne. The Studio Players comprise Gabrielle Beteag, Susanne Burgess, Joshua Conyers, Calvin Griffin, Joseph Lattanzi, and Brian Vu. Fiscal Year: 2021 Congressional District: 5 Grant Amount: $15,000 Category: Grants for Arts Projects Discipline: Opera Grant Period: 01/2021 - 03/2021 Bard College (aka ) 1864543-36 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-9800 To support a production of "Le roi Arthus (King Arthur) by composer Ernest Chausson at the Fisher Center's Sosnoff Theater. -

Proving up NEW YORK PREMIERE

2018-19 SEASON Celebrating 30 Years OPENING NIGHT Proving Up NEW YORK PREMIERE MUSIC BY Missy Mazzoli LIBRETTO BY Royce Vavrek Adapted from the short story “Proving Up” by Karen Russell Co-commissioned by Washington National Opera, Opera Omaha, and Miller Theatre at Columbia University © 2018 G. Schirmer Inc. IN A NEW PRODUCTION BY OPERA OMAHA Wednesday, September 26, 8 p.m. | Friday, September 28, 8 p.m. Click on a section to learn more OVERVIEW SYNOPSIS CREATIVE TEAM CAST NOTES PHOTOS PRESS COVERAGE PRESS RELEASE OVERVIEW Proving Up Wednesday, September 26, 8 p.m. | Friday, September 28, 8 p.m. The performance runs approximately 75 minutes with no intermission. Composer Missy Mazzoli and librettist Royce Vavrek thrilled audiences and critics alike in 2016 with the premiere of their opera Breaking the Waves. This dynamic creative duo reunites for Proving Up, a harrowing tale of a family’s pursuit of the American Dream set in post-Civil War Nebraska. Miller’s 30th Anniversary Season opens with the New York pre- miere of this chamber opera that is by turns optimistic, exultant, and menacing. Major support for Proving Up is provided by Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts and H.F. Lenfest Fund of The Philadelphia Foundation Opera Omaha’s New York appearance is generously supported by Omaha Steaks Proving Up SYNOPSIS Somewhere in the plains of the young U.S. State of Nebraska, 1868 The Zegners – Ma, Pa, and their two young sons Peter and Miles – have moved to Nebraska from the east coast following the Civil War, prompted by the passing of the U.S. -

BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music) Announces Yours Theirs Ours, a New Season of 16 Engagements by Artists Sharing Bold Ideas and Giving Voice, from March 23—June 30

BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music) announces Yours Theirs Ours, a new season of 16 engagements by artists sharing bold ideas and giving voice, from March 23—June 30 Bloomberg Philanthropies is the Season Sponsor Jan 14, 2020/Brooklyn, NY—BAM Artistic Director David Binder today announced programming for Yours Theirs Ours, a new season of 16 engagements by dynamic artists across the artistic spectrum—with many making their BAM debuts. Engagements will run from March 23—June 30 and will be presented in all of BAM’s venues and off-site. Binder said, “Yours Theirs Ours features a group of diverse, global and local artists who challenge us with fresh ideas from new perspectives. Their compelling work gives voice to those silenced and without power. Individually, these choreographers, directors, writers, composers, and visual artists address and reflect the challenges of our time; collectively, they create a resonant and welcoming season for everyone.” “We are thrilled by the innovation and ingenuity of David Binder’s first year of programming,” said BAM President Katy Clark. “Yours Theirs Ours offers a wide range of creative experiences by artists exploring urgent issues. BAM is appreciative of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ continued leadership as season sponsor and grateful to all of the supporters who make our programs possible.” Yours Theirs Ours programs March BLKNWS…………………………………………Kahlil Joseph………………………... page 1 Lungs……………………………………………. Old Vic, London; Duncan Macmillan, Matthew Warchus……... page 3 PROTO…………………………………………...Holly Herndon……………………….. page 5 April Tiona Nekkia McClodden…..……………………………………………………………page 5 Riz Ahmed……………………………………… …………………………………………page 6 Meeting in the Ladies’ Room: Black Femme Energy from the 80s, 90s, and Today………………………… Wesley Morris & Jenna Wortham... -

Houston Grand Opera Presents World Premiere of the House Without a Christmas Tree Family-Friendly Holiday Opera November 30–December 17 at George R

Houston Grand Opera Presents World Premiere of The House without a Christmas Tree Family-friendly holiday opera November 30–December 17 at George R. Brown Convention Center Houston, November 7, 2017— Houston Grand Opera (HGO) continues its series of holiday operas with the world premiere presentation of The House without a Christmas Tree by the widely admired composer/librettist team of Ricky Ian Gordon and Royce Vavrek, in the HGO Resilience Theater at the George R. Brown Convention Center. The opera is based on the uplifting story by Gail Rock and the beloved 1972 television film of the same name about a family that is healed by the holiday spirit. A precocious daughter struggles to understand her father’s resentment of the holidays and longs for a beautiful Christmas tree like other families have, to “make her house look happy.” The opera includes a new setting of the carol “Gather Around the Christmas Tree,” sung by a juvenile chorus. Tickets for the new venue are available at HGO.org. Group discounts are available. Parking for HGO’s performances will be available at the Avenida North garage located at 1815 Rusk Street, across from HGO’s new venue. A sky bridge connects the parking garage to the GRB, and there is clear signage directing patrons to the theater. More information about parking can be found here. Several HGO Studio alumni lead the cast: soprano Lauren Snouffer stars as young Addie Mills, baritone Daniel Belcher plays her father, and soprano Heidi Stober (now singing Cleopatra in Julius Caesar) takes the roles of the adult Adelaide Mills, her mother, Helen, and Addie’s teacher, Miss Thompson.