Enjoying the Quiet Life? Corporate Governance and Managerial Preferences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Price Competition with Satisficing Consumers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aberdeen University Research Archive Price Competition with Satisficing Consumers∗ Mauro Papiy Abstract The ‘satisficing’ heuristic by Simon (1955) has recently attracted attention both theoretically and experimentally. In this paper I study a price-competition model in which the consumer is satisficing and firms can influence his aspiration price via marketing. Unlike existing models, whether a price comparison is made depends on both pricing and marketing strategies. I fully characterize the unique symmetric equilibrium by investigating the implications of satisficing on various aspects of market competition. The proposed model can help explain well-documented economic phenomena, such as the positive correla- tion between marketing and prices observed in some markets. JEL codes: C79, D03, D43. Keywords: Aspiration Price, Bounded Rationality, Price Competition, Satisficing, Search. ∗This version: August 2017. I would like to thank the Editor of this journal, two anonymous referees, Ed Hopkins, Hans Hvide, Kohei Kawamura, Ran Spiegler, the semi- nar audience at universities of Aberdeen, East Anglia, and Trento, and the participants to the 2015 OLIGO workshop (Madrid) and the 2015 Econometric Society World Congress (Montreal) for their comments. Financial support from the Aberdeen Principal's Excel- lence Fund and the Scottish Institute for Research in Economics is gratefully acknowledged. Any error is my own responsibility. yBusiness School, University of Aberdeen - Edward Wright Building, Dunbar Street, AB24 3QY, Old Aberdeen, Scotland, UK. E-mail address: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction According to Herbert Simon (1955), in most global models of rational choice, all alternatives are eval- uated before a choice is made. -

ECON 1820: Behavioral Economics Spring 2015 Brown University Course Description Within Economics, the Standard Model of Be

ECON 1820: Behavioral Economics Spring 2015 Brown University Course Description Within economics, the standard model of behavior is that of a perfectly rational, self interested utility maximizer with unlimited cognitive resources. In many cases, this provides a good approximation to the types of behavior that economists are interested in. However, over the past 30 years, experimental and behavioral economists have documented ways in which the standard model is not just wrong, but is wrong in ways that are important for economic outcomes. Understanding these behaviors, and their implications, is one of the most exciting areas of current economic inquiry. The aim of this course is to provide a grounding in the main areas of study within behavioral economics, including temptation and self control, fairness and reciprocity, reference dependence, bounded rationality and choice under risk and uncertainty. For each area we will study three things: 1. The evidence that indicates that the standard economic model is missing some important behavior 2. The models that have been developed to capture these behaviors 3. Applications of these models to (for example) finance, labor and development economics As well as the standard lectures, homework assignments, exams and so on, you will be asked to participate in economic experiments, the data from which will be used to illustrate some of the principals in the course. There will also be a certain small degree of classroom ‘flipping’, with a portion of many lectures given over to group problem solving. Finally, an integral part of the course will be a research proposal that you must complete by the end of the course, outlining a novel piece of research that you would be interested in doing. -

Behavioral Economics and Marketing in Aid of Decision Making Among the Poor

Behavioral Economics and Marketing in Aid of Decision Making Among the Poor The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bertrand, Marianne, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Eldar Shafir. 2006. Behavioral economics and marketing in aid of decision making among the poor. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 25(1): 8-23. Published Version http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jppm.25.1.8 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:2962609 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Behavioral Economics and Marketing in Aid of Decision Making Among the Poor Marianne Bertrand, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Eldar Shafir This article considers several aspects of the economic decision making of the poor from the perspective of behavioral economics, and it focuses on potential contributions from marketing. Among other things, the authors consider some relevant facets of the social and institutional environments in which the poor interact, and they review some behavioral patterns that are likely to arise in these contexts. A behaviorally more informed perspective can help make sense of what might otherwise be considered “puzzles” in the economic comportment of the poor. A behavioral analysis suggests that substantial welfare changes could result from relatively minor policy interventions, and insightful marketing may provide much needed help in the design of such interventions. -

Esther Duflo Wins Clark Medal

Esther Duflo wins Clark medal http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2010/duflo-clark-0423.html?tmpl=compon... MIT’s influential poverty researcher heralded as best economist under age 40. Peter Dizikes, MIT News Office April 23, 2010 MIT economist Esther Duflo PhD ‘99, whose influential research has prompted new ways of fighting poverty around the globe, was named winner today of the John Bates Clark medal. Duflo is the second woman to receive the award, which ranks below only the Nobel Prize in prestige within the economics profession and is considered a reliable indicator of future Nobel consideration (about 40 percent of past recipients have won a Nobel). Duflo, a 37-year-old native of France, is the Abdul Esther Duflo, the Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and and Development Economics at MIT, was named the winner of the Development Economics at MIT and a director of 2010 John Bates Clark medal. MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab Photo - Photo: L. Barry Hetherington (J-PAL). Her work uses randomized field experiments to identify highly specific programs that can alleviate poverty, ranging from low-cost medical treatments to innovative education programs. Duflo, who officially found out about the medal via a phone call earlier today, says she regards the medal as “one for the team,” meaning the many researchers who have contributed to the renewal of development economics. “This is a great honor,” Duflo told MIT News. “Not only for me, but my colleagues and MIT. Development economics has changed radically over the last 10 years, and this is recognition of the work many people are doing.” The American Economic Association, which gives the Clark medal to the top economist under age 40, said Duflo had distinguished herself through “definitive contributions” in the field of development economics. -

Sendhil Mullainathan [email protected]

Sendhil Mullainathan [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________________________ Education HARVARD UNIVERSITY, CAMBRIDGE, MA, 1993-1998 PhD in Economics Dissertation Topic: Essays in Applied Microeconomics Advisors: Drew Fudenberg, Lawrence Katz, and Andrei Shleifer CORNELL UNIVERSITY, ITHACA, NY, 1990-1993 B.A. in Computer Science, Economics, and Mathematics, magna cum laude Fields of Interest Behavioral Economics, Poverty, Applied Econometrics, Machine Learning Professional Affiliations UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Roman Family University Professor of Computation and Behavioral Science, January 1, 2019 to present. University Professor, Professor of Computational and Behavioral Science, and George C. Tiao Faculty Fellow, Booth School of Business, July 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018. HARVARD UNIVERSITY Robert C Waggoner Professor of Economics, 2015 to 2018. Affiliate in Computer Science, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, July 1, 2016 to 2018. Professor of Economics, 2004 (September) to 2015. UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Visiting Professor, Booth School of Business, 2016-17. MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Mark Hyman Jr. Career Development Associate Professor, 2002-2004 Mark Hyman Jr. Career Development Assistant Professor, 2000-2002 Assistant Professor, 1998- 2000 SELECTED AFFILIATIONS Co - Founder and Senior Scientific Director, ideas42 Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research Founding Member, Poverty Action Lab Member, American Academy of Arts -

Chapter 4: Conceptual Illusions

CHAPTER 4: CONCEPTUAL ILLUSIONS In this chapter we will consider some fallacies and peculiarities of the way we reason. We’ll briefly consider the fallacy of denying the evidence and then confirmation bias, the paradox of choice, the conjunction fallacy and implicit bias. 1 DENYING THE EVIDENCE My scale is broken. It shows a higher figure every day so I have to keep adjusting it down. 2 CONFIRMATION BIAS "It is the peculiar and perpetual error of the human understanding to be more moved and excited by affirmatives than by negatives." --Francis Bacon Confirmation bias refers to a type of selective thinking whereby one tends to notice and to look for what confirms one's beliefs, and to ignore, not look for, or undervalue the relevance of what contradicts one's beliefs. For example, if you believe that during a full moon there is an increase in admissions to the emergency room where you work, you will take notice of admissions during a full moon, but be inattentive to the moon when admissions occur during other nights of the month. A tendency to do this over time unjustifiably strengthens your belief in the relationship between the full moon and accidents and other lunar effects. 52 This tendency to give more attention and weight to data that support our beliefs than we do to contrary data is especially pernicious when our beliefs are little more than prejudices. If our beliefs are firmly established on solid evidence and valid confirmatory experiments, the tendency to give more attention and weight to data that fit with our beliefs should not lead us astray as a rule. -

Sendhil Mullainathan Education Fields of Interest Professional

Sendhil Mullainathan Robert C Waggoner Professor of Economics Littauer Center M-18 Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] 617 496 2720 _____________________________________________________________________________________ Education HARVARD UNIVERSITY, CAMBRIDGE, MA, 1993-1998 PhD in Economics Dissertation Topic: Essays in Applied Microeconomics Advisors: Drew Fudenberg, Lawrence Katz, and Andrei Shleifer CORNELL UNIVERSITY, ITHACA, NY, 1990-1993 B.A. in Computer Science, Economics, and Mathematics, magna cum laude Fields of Interest Behavioral Economics, Poverty, Applied Econometrics, Machine Learning Professional Affiliations HARVARD UNIVERSITY Robert C Waggoner Professor of Economics, 2015 to present. Affiliate in Computer Science, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, July 1, 2016 to present Professor of Economics, 2004 (September) to 2015. UNVIRSITY OF CHICAGO Visiting Professor, Booth School of Business, 2016-17. MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Mark Hyman Jr. Career Development Associate Professor, 2002-2004 Mark Hyman Jr. Career Development Assistant Professor, 2000-2002 Assistant Professor, 1998- 2000 SELECTED AFFILIATIONS Co - Founder and Senior Scientific Director, ideas42 Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research Founding Member, Poverty Action Lab Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences Contributing Writer, New York Times Sendhil Mullainathan __________________________________________________________________ Books Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, joint with Eldar Shafir, 2013. New York, NY: Times Books Policy and Choice: Public Finance through the Lens of Behavioral Economics, joint with William J Congdon and Jeffrey Kling, 2011. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press Work in Progress Machine Learning and Econometrics: Prediction, Estimation and Big Data, joint with Jann Spiess, book manuscript in preparation. “Multiple Hypothesis Testing in Experiments: A Machine Learning Approach,” joint with Jens Ludwig and Jann Spiess, in preparation. -

CORRUPTION Abhijit Banerjee Sendhil Mullainathan Rema Hanna

CORRUPTION Abhijit Banerjee Sendhil Mullainathan Rema Hanna WORKING PAPER 17968 NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CORRUPTION Abhijit Banerjee Sendhil Mullainathan Rema Hanna Working Paper 17968 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17968 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2012 The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Abhijit Banerjee, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Rema Hanna. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Corruption Abhijit Banerjee, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Rema Hanna NBER Working Paper No. 17968 April 2012 JEL No. D02,O10,O12,O43 ABSTRACT In this paper, we provide a new framework for analyzing corruption in public bureaucracies. The standard way to model corruption is as an example of moral hazard, which then leads to a focus on better monitoring and stricter penalties with the eradication of corruption as the final goal. We propose an alternative approach which emphasizes why corruption arises in the first place. Corruption is modeled as a consequence of the interaction between the underlying task being performed by bureaucrat, the bureaucrat's private incentives and what the principal can observe and control. This allows us to study not just corruption but also other distortions that arise simultaneously with corruption, such as red-tape and ultimately, the quality and efficiency of the public services provided, and how these outcomes vary depending on the specific features of this task. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

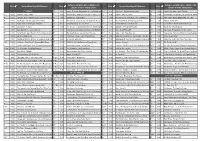

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

Nber Working Paper Series

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES REEVALUATING THE MODERNIZATION HYPOTHESIS Daron Acemoglu Simon Johnson James A. Robinson Pierre Yared Working Paper 13334 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13334 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2007 We are grateful for the comments and suggestions of José Antionio Cheibub, Jorge Dominguez, Peter Hall, and Susan Stokes. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson, and Pierre Yared. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Reevaluating the Modernization Hypothesis Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson, and Pierre Yared NBER Working Paper No. 13334 August 2007 JEL No. O10,P16 ABSTRACT This paper revisits and critically reevaluates the widely-accepted modernization hypothesis which claims that per capita income causes the creation and the consolidation of democracy. We argue that existing studies find support for this hypothesis because they fail to control for the presence of omitted variables. There are many underlying historical factors that affect both the level of income per capita and the likelihood of democracy in a country, and failing to control for these factors may introduce a spurious relationship between income and democracy. We show that controlling for these historical factors by including fixed country effects removes the correlation between income and democracy, as well as the correlation between income and the likelihood of transitions to and from democratic regimes. -

Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation

THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE • VOL. LVII, NO. 3 • JUNE 2002 Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation RAFAEL LA PORTA, FLORENCIO LOPEZ-DE-SILANES, ANDREI SHLEIFER, and ROBERT VISHNY* ABSTRACT We present a model of the effects of legal protection of minority shareholders and of cash-flow ownership by a controlling shareholder on the valuation of firms. We then test this model using a sample of 539 large firms from 27 wealthy economies. Consistent with the model, we find evidence of higher valuation of firms in coun- tries with better protection of minority shareholders and in firms with higher cash- flow ownership by the controlling shareholder. RECENT RESEARCH SUGGESTS THAT THE EXTENT of legal protection of investors in a country is an important determinant of the development of its financial markets. Where laws are protective of outside investors and well enforced, investors are willing to finance firms, and financial markets are both broader and more valuable. In contrast, where laws are unprotective of investors, the development of financial markets is stunted. Moreover, systematic differ- ences among countries in the structure of laws and their enforcement, such as the historical origin of their laws, account for the differences in financial development ~La Porta et al. ~1997, 1998!!. How does better protection of outside investors ~both shareholders and creditors! promote financial market development? When their rights are bet- ter protected by the law, outside investors are willing to pay more for finan- cial assets such as equity and debt. They pay more because they recognize that, with better legal protection, more of the firm’s profits would come back to them as interest or dividends as opposed to being expropriated by the entrepreneur who controls the firm.