INFORMATION to USERS the Quality of This Reproduction Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Nomination Form

BROADVIEW HISTORIC DISTRICT 5151 14TH STREET NORTH ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA 22205 HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION FORM SEPTEMBER 2014 Department of Community Planning, Housing, and Development Neighborhood Services Division, Historic Preservation 2100 Clarendon Boulevard, Suite 700 Arlington, Virginia 22201 ARLINGTON COUNTY REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION FORM 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Broadview Other Names: The Old Lacey House; Storybook House 2. LOCATION OF PROPERTY Street and Number: 5151 14th Street North County, State, Zip Code: Arlington, Virginia, 22205 3. TYPE OF PROPERTY A. Ownership of Property X Private Public Local State Federal B. Category of Property X Private Public Local State Federal C. Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings sites 1 structures objects 1 1 Total D. Listing in the National Register of Historic Places Yes X No 4. FUNCTION OR USE Historic Functions: Domestic/single-family dwelling/multi-family dwelling Current Functions: Domestic/single-family dwelling. 1 5. DESCRIPTION OF PROPERTY Site: Broadview is located at 5151 14th Street North in the Waycroft-Woodlawn neighborhood of Arlington, Virginia (App. 1, Fig. 1). In the early-twentieth century, the property spanned over 223 acres (App. 1, Fig. 10). In 1934, under the ownership of Sallie Lacey Johnston, the property’s 50- acres were defined by present-day 16th Street North on the north, Washington Boulevard on the south, North Edison Street on the east, and North George Mason Drive on the west. The front of the building (east elevation) faced towards North Edison Street and a drive extended northwest from the corner of North Edison Street and Washington Boulevard to the house. -

Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society

Library of Congress Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Volume 12 COLLECTIONS OF THE MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XII. ST. PAUL, MINN. PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY. DECEMBER, 1908. No. 2 F601 .M66 2d set HARRISON & SMITH CO., PRINTERS, LITHOGRAPHERS, AND BOOKBINDERS, MINNEAPOLIS, MINN. OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY. Nathaniel P. Langford, President. William H. Lightner, Vice-President. Charles P. Noyes, Second Vice-President. Henry P. Upham, Treasurer. Warren Upham, Secretary and Librarian. David L. Kingsbury, Assistant Librarian. John Talman, Newspaper Department. COMMITTEE ON PUBLICATIONS. Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Volume 12 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.0866g Library of Congress Nathaniel P. Langford. Gen. James H. Baker. Rev. Edward C. Mitchell. COMMITTEE ON OBITUARIES. Hon. Edward P. Sanborn. John A. Stees. Gen. James H. Baker. The Secretary of the Society is ex officio a member of these Committees. PREFACE. This volume comprises papers and addresses presented before this Society during the last four years, from September, 1904, and biographic memorials of its members who have died during the years 1905 to 1908. Besides the addresses here published, several others have been presented in the meetings of the Society, which are otherwise published, wholly or in part, or are expected later to form parts of more extended publications, as follows. Professor William W. Folwell, in the Council Meeting on May 14, 1906, read a paper entitled “A New View of the Sioux Treaties of 1851”; and in the Annual Meeting of the Society on January 13, 1908, he presented an address, “The Minnesota Constitutional Conventions of 1857.” These addresses are partially embodied in his admirable concise history, “Minnesota, the North Star State,” published in October, 1908, by the Houghton Mifflin Company as a volume of 382 pages in their series of American Commonwealths. -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

Philadelphia Merchants, Trans-Atlantic Smuggling, and The

Friends in Low Places: Philadelphia Merchants, Trans-Atlantic Smuggling, and the Secret Deals that Saved the American Revolution By Tynan McMullen University of Colorado Boulder History Honors Thesis Defended 3 April 2020 Thesis Advisor Dr. Virginia Anderson, Department of History Defense Committee Dr. Miriam Kadia, Department of History Capt. Justin Colgrove, Department of Naval Science, USMC 1 Introduction Soldiers love to talk. From privates to generals, each soldier has an opinion, a fact, a story they cannot help themselves from telling. In the modern day, we see this in the form of leaked reports to newspapers and controversial interviews on major networks. On 25 May 1775, as the British American colonies braced themselves for war, an “Officer of distinguished Rank” was running his mouth in the Boston Weekly News-Letter. Boasting about the colonial army’s success during the capture of Fort Ticonderoga two weeks prior, this anonymous officer let details slip about a far more concerning issue. The officer remarked that British troops in Boston were preparing to march out to “give us battle” at Cambridge, but despite their need for ammunition “no Powder is to be found there at present” to supply the Massachusetts militia.1 This statement was not hyperbole. When George Washington took over the Continental Army on 15 June, three weeks later, he was shocked at the complete lack of munitions available to his troops. Two days after that, New England militiamen lost the battle of Bunker Hill in agonizing fashion, repelling a superior British force twice only to be forced back on the third assault. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi'om the original or copy submitted- Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from aity type of conçuter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to r i^ t in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427761 Lest the rebels come to power: The life of W illiam Dennison, 1815—1882, early Ohio Republican Mulligan, Thomas Cecil, Ph.D. -

The Prison Letters of Captain Joseph Scrivner Ambrose IV, C.S.A

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2005 Devotedly Yours: The Prison Letters of Captain Joseph Scrivner Ambrose IV, C.S.A. Rebeccah Helen Pedrick Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Genealogy Commons, Military History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pedrick, Rebeccah Helen, "Devotedly Yours: The Prison Letters of Captain Joseph Scrivner Ambrose IV, C.S.A." (2005). Honors Theses. 136. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/136 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Devotedly Yours: The Prison Letters of Captain Joseph Scrivner Ambrose, C.S.A." written by Rebeccah Pedrick 9 December 2005 Tales of war-valor, courage, intrigue, winners, losers, common men, outstanding officers. Such stories captivate, enthrall, and inspire each generation, though readers often feel distanced from the participants. The central figures of these tales are heroes, seemingly beyond the reach of ordinary men. Through a more intimate glimpse of one such figure, the affectionate letters of Joseph Scrivner Ambrose to his sister, written from prison during America's Civil War, perhaps one can find more than a hero- one can find a man with whom one can identify, a man who exemplifies the truth of the old adage, "Heroes are made, not born."1 The Man and His Heritage Joseph Scrivner Ambrose's family heritage bequeathed him legacies of valor in battle, restless thirsts for exploration, and deep religious conviction.2 Ancestors on both sides served their country both on the battlefield and in the home, raising large families and settling the far reaches of the young American nation. -

Guide to a Microfilm Edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records

-~-----', Guide to a Microfilm Edition of The Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records Helen McCann White Minnesota Historical Society . St. Paul . 1974 -------~-~~~~----~! Copyright. 1974 @by the Minnesota Historical Society Library of Congress Catalog Number:74-10395 International Standard Book Number:O-87351-091-7 This pamphlet and the microfilm edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records which it describes were made possible by a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission to the Minnesota Historical Society. Introduction THE PAPERS AND OFFICIAL RECORDS of Alexander Ramsey are the sixth collection to be microfilmed by the Minnesota Historical Society under a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission. They document the career of a man who may be charac terized as a 19th-century urban pioneer par excellence. Ramsey arrived in May, 1849, at the raw settlement of St. Paul in Minne sota Territory to assume his duties as its first territorial gov ernor. The 33-year-old Pennsylvanian took to the frontier his family, his education, and his political experience and built a good life there. Before he went to Minnesota, Ramsey had attended college for a time, taught school, studied law, and practiced his profession off and on for ten years. His political skills had been acquired in the Pennsylvania legislature and in the U.S. Congress, where he developed a subtlety and sophistication in politics that he used to lead the development of his adopted city and state. Ram sey1s papers and records reveal him as a down-to-earth, no-non sense man, serving with dignity throughout his career in the U.S. -

London Correctional Institution 2006 Inspection Report

CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTION INSPECTION COMMITTEE EVALUATION AND INSPECTION REPORT LONDON CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTION PREPARED AND SUBMITTED BY CIIC STAFF August 28, 2006 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………… 6 INSPECTION PROFILE………………………………………………………… 6 STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS OF INSPECTION ………………….……… 7 Attendance at General Meal Period ……………………………………… 7 Attendance at Programming ……………………………………………… 7 FINDINGS SUMMARY ………………………………………………………… 7 INSTITUTIONAL OVERVIEW ………………………………………………….. 8 Mission Statement ………………………………………………………… 8 Physical Property ……………………………………………………….… 8 Farm ………………………………………………………………………. 9 Significant Improvements In Recent Years……………………………… 9 Powerhouse, Water Treatment, Sewage Plants …………………………… 9 Business Office ………………………………………………………… 10 Accreditation ……………………………………………………………… 10 Staff Distribution………………………………………………………… 10 TABLE 1. Staff Distribution: Race and Gender…………………. 10 Deputy Warden of Special Services………………………………………. 11 Deputy Warden of Operations……………………………………………. 11 Deputy Warden of Administration………………………………………… 11 INMATE PROGRAM SERVICES: EDUCATION, SPECIFIC PROGRAMS, WORK OPPORTUNITIES ……………………………………………………..… 11 Inmate Program Services ………………………………………….……… 11 Jobs and Programming …………………………………………………… 12 Other Programs …………………………………………………………… 12 Program Directory ………………………………………………………… 13 TABLE 2. London Correctional Institution Program Directory … 14 Mental Health and Recovery Program …………………………………… 15 Educational Programming. ……………………………………………… 16 Dog Program ……………………………………………………………… -

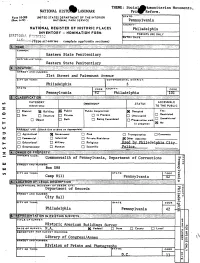

Teiiii^ !!Ti;;:!L||^^ -STATUS ACCESSIBLE Categbry OWNERSHIP (Check One) to the PUBLIC

THEME: Socia Movements , NATIONAL HIST01 'LANDMARK Pri Re form. Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) • f NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Pennsylvania COUNTY; NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Philadelphia INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY {NATTOIT/J, FT5703IC' ENTRY DATE ^mWiij.nitf.'TjypQ all entries - complete applicable sections) '^^^^^^^K^y^^iy^' SitlllP W!i*:': %$$$SX ^ v;!f ';^^:-M^ '^'''^S^iii^^X^i^i^S^^^ :- • y;;£ ' ' ' . :':^:- -• * : :V COMMON: Eastern State Penitentiary AND/OR HISTORIJC: [ Eastern State Penitentiary i'**i* ^Sririiii1 :*. -: . ' ',&$;':•&. \-Stf: -: #gy&. Vii'Sviv:; .<:. :':.x:x.?:.S :•:;:..:-.:;:;.:: : . :: r :' ..:•: :1.';V.':::::::1 -?:--:i^ . ....:. :•;. ¥.:? :?:>.::;:•:•:.:¥:" .v:::::^1:;:gS::::::S*;v*ri-:':i ftyWf*,^ ;:-.;. ; .;.^:|:.:. ....;- , ••;.,.; ,: ; : '.,:• f-^..^ ;. .S:.';: >• tell^•fcf S*fV;| :*;Wfl :-K;:; • ; -f,/ •.. ••, •••<>•' • •• .;.;.•• • ;.:;••••: •••/:' ..... :.:• :'. :•:.:: ;'V •': v,-"::;.:-;.:;.: :•;•: ^V - -•;.•: ;:>:••:;. .:.'-;.,.::---7:-::i.;v ' '''-:' jji.:'./s iSgfci'S ,':':Sv:;,: ' K JftiSiSWix?-: S.^:!:?--;:. ; S*;.?. S '«:;.;Si-.--:':.-'.;"-- :':: -::x: '; ^.^-Sy .:;•?.,!.;:.•::;•" • . STREET AND NUMBER: 21st Street and Fairmount Avenue CITY OR TOWN: CONGRE SSIONAU DISTRICT: Philadelphia 3 STATE { CODE COUNTY CODE f Pennsylvania 42 Philadelpftia lol teiiii^ !!ti;;:!l||^^ -STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGbRY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC C3 District (Jg Building S3 P"b''c Public Acquisition: S3 Occupied Yes: r-i n • j Q Restricted Q Site Q Structure D Private O ln Process LJ Unoccupied ' — ' D Object D Both Q Being Considere<i LJr—i Preservationo worki D*— ' Unrestricted in progress IS No 'PRESENT USE (Check One or More ea Appropriate) D Agricultural \ Q§ Government Q Park O Transportation CD Comments Q Commercial f CD Industrial Q Private Residence JS< Other (Sped*,) D Educotionalj D Military Q Religious Used bv Philadelphia C}tv D Entertainment Q Museum Q Scientific Police. -

Ohio Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Ohio ! ~ Department/ ,-. \ of () and Correction Annual Report Fiscal Year 1976 '1 A. Rhodes e F. Denton STATE Of OHIO DEPARTMENT OF REHABILITATION AND CORRECTION 1050 FI'HWO}/ Drl .., North, Suite .co3 ColumbuJ, ohio A322~ JAMES A. ftHODES, Oo"r~' (614) 0466-6190 GrOAOE " DENtON, DltIdor Janu~ry 31, 1977 The Honorable JIlIl>lG A. Rhodes, Governor of Ohio Statehouae 1:.>1umbuG, Ohio 43215 Ilcar Governor Rhodes: Pursuant t<> Sectiona 5120.32, 5120.33 Illld 5120.35 of the Ohio Revised Code, the Annual Report of the Ohio Depnrtment of Rehabilitation rmd Correction for Fiacal Year 1976 is hereby submitted. Thib report includes Ii financial statement of Departmental operationo over the past fiscal year Illld a narrati"e summary of major a"tivitiea and developmenta during this period. 4Georg~~, ~4u Director GFD/ja CONTENTS About the Department .................................... 1 Administration ..........................................2 Officers of the Department . ..... .4 Enlployee Training .......................................5 Institutional Operations .................................... 0 Institution Citizen Councils . ........8 The Prison Population ..................................9 1976 Prison Commitments .............................. 10 Inmate Grievances and Disciplinary Appeals .......... ....... 15 Inmate Education Programs .............................. 15 Inmate Medical Services ........................ ....... 17 Home Furlough Program . ....... 18 -

Soldiers of Long Odds: Confederate Operatives Combat the United

Soldiers of Long Odds: Confederate Operatives Combat the United States from Within by Stephen A. Thompson Intrepid Consulting Services, Inc. Mattoon, Illinois Illinois State Historical Society History Symposium The Civil War Part III: Copperheads, Contraband and the Rebirth of Freedom Eastern Illinois University 27 March 2014 Preface For the purposes of this forum, the featured contextual development was undertaken for the express reason of introducing the subject matter to a wider audience through a broad presentation of Confederate States of America (CSA) insurrection, subversion and sabotage activities that took place under the expansive standard “Northwest Conspiracy” during 1864 and 1865. This examination is by no means comprehensive and the context is worthy of extensive 21st century research, assessment and presentation. The movement of Captain Thomas Henry Hines, CSA, military commander of the Confederate Mission to Canada, through the contextual timeline presents the best opportunity to introduce personalities, places and activities of consequence. Since Hines led tactical operations and interacted with the public-at-large during this period, the narrative of his activity assists in revealing Civil War-era contextual significance on the national, regional, State of Illinois and local levels. Detailing the activities of Hines and his Canadian Squadron operatives in the northwest is vital to the acknowledgment of significance at all levels. Hence, the prolonged contextual development contained within this treatise. Stephen A. Thompson Mattoon, Illinois 21 January 2014 Cover Image – Captain Thomas Henry Hines, CSA. Toronto, Canada, 1864. Courtesy of Mrs. John J. Winn i Context Dire straits is the only way to describe the predicament in which the governing hierarchy of Confederate States of America found itself as the year of 1864 began. -

Seventeenth Through Nineteenth Century Philadelphia Quakers As the First Advocates for Insane, Imprisoned, and Impoverishe

Seventeenth through Nineteenth scholars Hugh Barbour and J. William Frost Century Philadelphia Quakers as the note how “In the English Northwest, Fox and Nayler were at first violently beaten or stoned First Advocates for Insane, and called Puritans.”[1] Friends seeking to Imprisoned, and Impoverished escape religious intolerance in England clashed Populations with Puritan ideology in the early American colonies. The average Quaker was ostracized and persecuted in England, and more so in New Joanna Riley England. Puritans carried out harsh, cruel Senior, Secondary Education/Social Studies punishments freely in the new world, effectively stunting the spread of Quakerism in The Society of Friends, especially in the New England. As a result, Philadelphia city of Philadelphia, was the only group in the provided ample audiences who would attend seventeenth century through mid-nineteenth weekly, monthly, and annual major meetings, century to align themselves with the plight of but also to further advancement in policy and those deemed insane, imprisoned, or reform efforts. impoverished. While the connection to the Concerned with the lack of Quaker insane was seemingly decided on by those institutions for those within the Society of outside of the Society of Friends, their Friends, and excluded from English first-hand experience of being thrown into institutions, they began founding their own. prison simply for being Quaker brought to light Originally, these places were to be created by the awful conditions within. Women served not and for the Quakers themselves, in order to only as ministers and proponents within the better facilitate rehabilitation to fellow Friends. Quaker movement, but also as caregivers and Gradually, they expanded their mission to nurses within the institutions created by the include those outside the faith; Quaker or not, Friends in order to improve society as a whole.