Identity, Place and Displacement in the Visual Art of Female Artists at the Vaal University of Technology (VUT), 1994-2004 by Ju

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

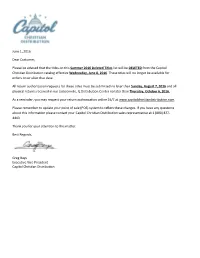

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please Be Advised That the Titles On

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please be advised that the titles on this Summer 2016 Deleted Titles list will be DELETED from the Capitol Christian Distribution catalog effective Wednesday, June 8, 2016. These titles will no longer be available for orders on or after that date. All return authorization requests for these titles must be submitted no later than Sunday, August 7, 2016 and all physical returns received in our Jacksonville, IL Distribution Center no later than Thursday, October 6, 2016. As a reminder, you may request your return authorization online 24/7 at www.capitolchristiandistribution.com. Please remember to update your point of sale (POS) system to reflect these changes. If you have any questions about this information please contact your Capitol Christian Distribution sales representative at 1 (800) 877- 4443. Thank you for your attention to this matter. Best Regards, Greg Bays Executive Vice President Capitol Christian Distribution CAPITOL CHRISTIAN DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2016 DELETED TITLES LIST Return Authorization Due Date August 7, 2016 • Physical Returns Due Date October 6, 2016 RECORDED MUSIC ARTIST TITLE UPC LABEL CONFIG Amy Grant Amy Grant 094639678525 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant My Father's Eyes 094639678624 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Never Alone 094639678723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Straight Ahead 094639679225 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Unguarded 094639679324 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant House Of Love 094639679829 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Behind The Eyes 094639680023 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant A Christmas To Remember 094639680122 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Simple Things 094639735723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Icon 5099973589624 Amy Grant Productions CD Seventh Day Slumber Finally Awake 094635270525 BEC Recordings CD Manafest Glory 094637094129 BEC Recordings CD KJ-52 The Yearbook 094637829523 BEC Recordings CD Hawk Nelson Hawk Nelson Is My Friend 094639418527 BEC Recordings CD The O.C. -

1 Case Study Interview with David Paton Artist / Academic Senior

Case study interview with David Paton Teaching Artist / Academic In their first year, Fine Art students at the University Senior Lecturer: Visual Art of Johannesburg (UJ, formerly the Technikon University of Johannesburg, South Africa Witwatersrand) have a project in printmaking to produce hade-made books based on the Bill of Rights. This involvement with the book has its roots in an interest in the book arts by current and former staff in the department who include, Kim Berman, Philippa Hobbs, Sr. Sheila Flynn and Willem Boshoff. Many important book artists in South Africa: Giulio Tambellini, Flip Hatting, Sonya Strafella and Carol Hofmeyr amongst others, received their introduction to the genre as students of the Department. UJ’s Graphic Design students undertake book-design in their 3rd and 4th year, but they print and bind them outside of the university. At the Michaelis School of Fine Art (University of Cape Town) their printmaking department has, for many years, included tuition in fine press and artists’ books, with post-graduate students sometimes www.theartistsbook.org.za producing artists’ books as part of their output. Some David Paton is the creator of this research website, of these books can be found in the School’s Katrine made to share information, development and ideas Harries Print Cabinet (KHPK – found at http://cca. around the South African Artist’s Book over the last uct.ac.za/collections/print-cabinet/). Most Fine Art 15 years. It shows a vast range of the prolific artists’ Departments of Universities of Technology (formerly books production in South Africa, with a searchable ‘Technikons’) such as the Durban University of database of artists, including images of their books. -

May 2008 Violence Against Foreign Nationals in South Africa

MAYY 2000088 VIIOLLEENCE AGGAAIINNSSTT FOORREEIIGGNN NNAATTIOONNAALLSS IINN SSOUTTHH AAFRRICCAA UNNDDEERSSTANNDDINNGG CCAAUUSSEES AANNDD EEVVAALUUAATTIINNG REESPPONNSSEESS By Jean Pierre Misago, Tamlyn Monson, Tara Polzer and Loren Landau April 2010 Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CoRMSA) and Forced Migration Studies Programme MAY 2008 VIOLENCE AGAINST FOREIGN NATIONALS IN SOUTH AFRICA: UNDERSTANDING CAUSES AND EVALUATING RESPONSES Jean Pierre Misago, Tamlyn Monson, Tara Polzer and Loren Landau Forced Migration Studies Programme (FMSP), University of the Witwatersrand and Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CoRMSA) April 2010 2 This research report was produced by the FORCED MIGRATION STUDIES PROGRAMME at the University of the Witwatersrand. The report was written by Jean Pierre Misago, Tamlyn Monson and Tara Polzer. The research was conducted by Jean Pierre Misago, Tamlyn Monson, Vicki Igglesden, Dumisani Mngadi, Gugulethu Nhlapo, Khangelani Moyo, Mpumi Mnqapu and Xolani Tshabalala. This report was funded by the Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CoRMSA) with support from Oxfam GB and Atlantic Philanthropies South Africa. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion in the report are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Oxfam GB. Based in Johannesburg, the Forced Migration Studies Programme (FMSP) is an internationally engaged; Africa-oriented and Africa-based centre of excellence for research and teaching that helps shape global discourse on migration; aid and social transformation. The Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CoRMSA) is the South African national network of organisations working with refugees and migrants. For more information about the FMSP see www.migration.org.za . -

February 2021 Official Publication of Alamitos Bay Yacht Club Volume 94 • Number 2 January Raft Up

February 2021 Official Publication of Alamitos Bay Yacht Club Volume 94 • Number 2 january raft up ads, how does one figure out a way to spend a Saturday evening when we’re not supposed to travel or get within six feet of anyone other than who you live with and when there are no bars or restaurants or the Club open? GSimple, just email or text a few of your ABYC friends (little advance warning is needed) and suggest a sunset rafting. The Taughers, Heavrin/Reeds, Clantons, Bells and Ott-Conns had a perfectly delightful time one January evening...wish you all were there! Dana Bell inside Manager’s Corner ............................................. 2 Commodore’s Comments............................... 2-3 Vice Verses ....................................................... 4 Rear View .......................................................... 4 Fleet Captains Log ............................................ 4 sav e the date Rules Quiz #75............................................ 5 & 7 Friday Night Patio......................... Feb 5,12,19,26 Membership Report ........................................... 5 Super Bowl ..........................................February 7 Juniors............................................................... 6 Zoom Membership Meeting ..............February 19 Eight Bells ......................................................... 6 Hails From the Fleets ................................. 10-11 Full ABYC Calendar sou’wester • february 2021 • page 1 manager’scorner t a recent General Membership meeting, members asked about how the ABYC employees are doing and how they are getting along through this pandemic. AThe short answer is that our regular staff is doing just fine. But rather than have me write about it, I have asked them to express their thoughts to you in their own words. Sheila Mattox - “I am doing well. I feel very lucky that I haven’t had any symptoms of the COVID-19 virus and haven’t felt the need to be tested. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Download a PDF Preview

Judith Mason Anne Sassoon Leora Maltz-Leca Kate McCrickard Copyright © 2010 the artist, the authors and David Krut Publishing ISBN: 978-0-9814328-2-3 Editor and Project Manager Bronwyn Law-Viljoen Designer Ellen Papciak-Rose Photo credits Susan Byrne, all photographs of the artist’s work Cover image Inside/Out, 2009 Gouache on panel, 91.4 x 68.6 cm These fragments from a South African journey are now fragments of memory, salvaged and celebrated in paint. Printed by Keyprint, Johannesburg Distributed in South Africa by David Krut Publishing cc. 140 Jan Smuts Avenue Parkwood, 2193 South Africa t +27 (0)11 880 5648 f +27 (0)11 880 6368 [email protected] Distributed in North America by David Krut Projects 526 West 26th Street, #816 New York, NY 10001 USA t +1 212 255 3094 f +1 212 400 2600 [email protected] www.davidkrutpublishing.com www.taxiartbooks.com CONTENTS 7 INTRODUCTION Judith Mason 28 COLLECTING EVIDENCE: ART AND THE APARTHEID STATE Anne Sassoon 50 THE LOGIC OF THE RELIC: TRACES OF HISTORY IN STONE AND MILK Leora Maltz-Leca 77 EXILE ON MAIN STREET: THE AMERICAN WORKS OF PAUL STOPFORTH, 1989–2009 Kate McCrickard 92 Selected Exhibitions 94 Selected Bibliography Honours and Awards 95 Collections Biographies 96 Wounded Man, 1988 Charcoal on paper, 76 x 56 cm Acknowledgements 6 INTRODUCTION Judith Mason Some decades ago, a certain man died while When, later, Stopforth drew Steve Biko’s bruised corpse, being interrogated by the South African Secu- the viewer felt that she was at the autopsy, spinning a rity Police. -

Nuusbrief / Newsletter Augustus / August 2011

Nuusbrief / Newsletter Augustus / August 2011 We are more than half way through 2011 and indeed Stellenbosch Arts Association has been offering a wide spectrum of activities, not only for artists but also for art lovers of all ages. Our monthly member meetings were very well attended, one of the highlights being Barry Gibb’s talk on Auguste Rodin-film snippets from Camille Claude were shown and reference was made to greats such as Michelangelo and Henry Moore. Daniel Louw presented a series of six talks on Icons: windows into eternity, during which the focus shifted from spirituality to corporality, from the sublime to the ridiculous and from life to death. We recently had the opportunity to watch the graffiti artist’s, Banksy's, first film (Exit Through the Gift Shop) billed as "the world's first street art disaster movie". The film was released in the UK on 5 March 2010 and in January 2011 it was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary. Our first workshop was presented by Marieke Kruger from Paarl with the theme, female figure studies. This was followed by Lorraine Blumer’s painting course and Lenie Harley’s cement sculpturing courses. What is more, we co-sponsored a holiday art project during the June school holiday for children aged 6 to 14 years in collaboration with Sasol Art Museum. We also presented a second workshop on comic art for teenagers, presented by Vernon Fourie. This was even attended by two fathers accompanying their sons! There was a special request for a follow- up of the comic course during the September school holiday. -

An Interview with Jon Foreman

December 2011 All things concerning MYC this month. CONNECT Get connected. “It's the simple, humble kid who's faithful and attentive to the Holy Spirit-- that's where it begins.” AN INTERVIEW WITH JON FOREMAN I recently read an article in Group more introspective-maybe the song possess, you know? That analogy plays out magazine that was an interview with Jon becomes a vehicle to discuss things you in other ways-a girl who's incredibly good- Foremen, the frontman for Switchfoot. I otherwise couldn't talk about. And that's looking will be cursed with that all her life thought you guys would enjoy reading some where I am at today,using the transcendence unless she learns there's more to her life. of it, so here it is: of music to be more honest than I would be When I look at culture, I see we have so in a conversation. I would say I write songs many gifts given to us that allow us to be Interviewer: What role has music had in about the things I don't understand, and the lazy. I've heard it said that any culture that forming your identity as a follower of Christ? biggest mysteries to me are probably makes ease its goal has already begun its Foreman: Music has been an integral part of women, deity, and politics. demise-I can't think of any nation where this my life ever since I can remember. When I would more relevant that my own. The Interviewer: In "Vice Verses" there's the lyric: was a kid I just loved the way that it felt to United States has become the culture of "Every blessing comes with a set of curses." listen to music. -

Annual Report 2004 Report Annual

cover_ARP 1.7.2005 9:15 Page 1 annual report 2004 implementation of activities and use of funds annual report report annual 2004 OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS ANNUAL REPORT 2004 The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Palais des Nations - CH-1211 Geneva 10 - Switzerland Telephone: 41 22/917 90 00 - Fax: 41 22/917 90 08 Web site: www.ohchr.org human rights RA 2004_ARP.qxd 1.7.2005 8:55 Page 1 ANNUAL report 2004 RA 2004_ARP.qxd 1.7.2005 8:55 Page 2 OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Prepared by the Resource Mobilization Unit of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Editorial Consultant: Andrew Lawday Design and Desktop Publishing by Latitudesign, Geneva Printed by Atar SA, Geneva Photographs: UNICEF/HQ02-0209/Nicole Toutounji; UN/186591C; UNICEF/HQ98-0441/Roger LeMoyne; UNICEF/HQ00-639/Roger LeMoyne; UN/153474C; UNICEF/HQ00-0761/Donna De Cesare; UN/148384C; UNICEF/HQ97-0525/Maggie Murray-Lee; UN/153752C. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. RA 2004_ARP.qxd 1.7.2005 8:55 Page 3 Table of contents Introduction by the High Commissioner . 5 EUROPE, CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS . -

Innibos@Casterbridge

Innibos@Casterbridge We have once again included a programme, specifically geared more towards our English-speaking patrons, at the beautiful Casterbridge Lifestyle Centre just outside White River. Theatre: Comedy / Stand up comedy Comedy Central Show With Mel Miller, Jason Goliath and Alfred Adriaan Grading: No u/14 Date and time: Fr 28 Jun 19:00; Sat 29 Jun 19:00 Venue: Casterbridge Barnyard, White River Duration: 80 minutes Price: R152 Supported by Comedy Central. If there is one thing South-Africans can do well, it’s laugh at ourselves. Join us for this hilarious laugh-a-minute show with some of South-Africa’s top comedians. For the first time, Comedy Central brings some authentic English South African stand-up comedy to the Innibos Arts Festival. Not to be missed! Festival artist: JUDITH MASON Living Lines and Impressions: A Glimpse of Judith Mason’s Editions and Drawings Curated by Tamar Mason WHITE RIVER GALLERY Casterbridge, White River 26 June -7 July Opening: Wednesday, 27 June 2019 18:00 For the last fifteen years of her life artist Judith Mason (1938-2016) lived and worked on a property close to White River, owned by her daughter and son-in-law, Tamar Mason and Mark Attwood. In her career spanning 50 years Mason excelled in different disciplines, painting, drawing, graphic printmaking, assemblage in mixed media and artist’s books. Her work is in leading South African corporate, state and private collections as well as in international collections. In 1966 Mason represented South Africa at the Venice Biennale, in 1971 at the Sao Paulo Biennale, in 1980 on the Houston Arts Festival and in 2008 at Art Basel, Miami Beach. -

City Church, Tallahassee, Blurring the Lines of Sacred and Secular Katelyn Medic

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 City Church, Tallahassee, Blurring the Lines of Sacred and Secular Katelyn Medic Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC CITY CHURCH, TALLAHASSEE: BLURRING THE LINES OF SACRED AND SECULAR By KATELYN MEDIC A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester 2014 Katelyn Medic defended this thesis on April 11, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Margaret Jackson Professor Directing Thesis Sarah Eyerly Committee Member Michael McVicar Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Make a joyful noise to the Lord, all the earth! Serve the Lord with gladness! Come into his presence with singing! (Psalm 100:1–2, ESV) I thank the leaders and members of City Church for allowing me to observe their worship practices. Their enthusiasm for worship has enriched this experience. I also thank the mentorship of the members of my committee, Margaret Jackson, Sarah Eyerly, and Michael McVicar. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT -

Pga01a36 Layout 1

Includes Family DVD section! Spring/Summer 2013 More Than 14,000 CDs and 210,000 Music Downloads Available at Christianbook.com! DVD— page A1 CD— CD— page 3 page 40 Christianbook.com 1–800–CHRISTIAN® New Releases THE BIBLE: MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE EPIC MINISERIES Table of Contents Discover songs that have been Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 inspired by the History Channel’s Bargains . .2, 38 epic miniseries! Includes “In Your Eyes” (Francesca Battis t elli); Collections . .4, 5, 7–9, 18–27, 33, 36, 37, 39 “Live Like That” (Sidewalk Proph - Contemporary & Pop . .28–31, back cover ets); “This Side of Heaven” (Chris August); “Love Come to Life” (Big Fitness Music DVDs . .21 Daddy Weave); “Crave” (For King Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 & Country); “Home” (Dara MacLean); “Wash Me Away” (Point of Grace); “Starting Line” (Jason Castro); and more. Gifts . .back cover $ 00 Hymns . .24–27 WRCD88876 Retail $9.99 . .CBD Price 5 Inspirational . .12, 13 Instrumental . .22, 23 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 sher in the springtime season of renewal with Messianic . .10 Umusic and movies that will rejuvenate your spir- it! Filled with new items, bestsellers, and customer Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 favorites, these pages showcase great gifts to New Releases . .3–5, back cover treasure for yourself, as well as share with friends and family. And we offer our best prices possible— Praise & Worship . .6–9, back cover every day! Rock & Alternative . .32, 33, back cover Worship Jesus through song with new releases from Michael English (page 5) and Kari Jobe (back Scenic Music DVDs . .20 cover); keep on track with your healthy living goals Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass .