BALL STATE UNIVERSITY / Muncie, Indiana Volume XXV / Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worship and Devotions

License, Copyright and Online Permission Statement Copyright © 2018 by Chalice Press. Outlines developed by an Editorial Advisory Team of outdoor ministry leaders representing six mainline Protestant denominations. Purchase of this resource gives license for its use, adaptation, and copying for programmatic use at one outdoor ministry or day camp core facility/operation (hereinafter, “FACILITY”) for up to one year from purchase. Governing bodies that own and operate more than one FACILITY must buy one copy of the resource for each FACILITY using the resource. Copies of the files may be made for use only within each FACILITY for staff and volunteer use only. Each FACILITY’s one-year permission now includes the use of this material for one year at up to three additional venues to expand the FACILITY’s reach into the local community. Examples would include offering outdoor ministry experiences at churches, schools, or community parks that are not part of your core FACILITY program. Copies of the files are for programming use only by staff and volunteers, and distribution for resale is strictly prohibited in any form electronically or in hard copy such as printing, copying, website posting/re-posting, emails, etc. Use of sí se puede® is by permission from United Farmworkers Union and Cesar Chavez Foundation. Use of this phrase outside of camp activities is not covered by this purchase and must be negotiated directly with UFW. Use of “May Peace Prevail on Earth” is by permission from World Peace Prayer Society. It can be freely used to promote peace but not for any commercial venture. -

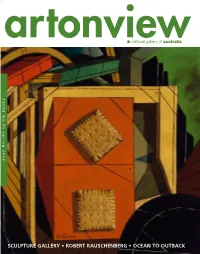

Artonview 51.Pdf

artonview art o n v i ew ISSUE No.51 ISS ue SPRING n o.51 spring 2007 2007 NATIONAL GALLERY OF GALLERY AUSTRALIA Richard Bell Australian art it’s an Aboriginal thing 2006 synthetic polymer paint on canvas Acquired 2006 TarraWarra Museum of Art collection courtesy the artist and Bellas Milani Gallery 13 October 2007 – 10 February 2008 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra CELEBRATING¬¬YEARS A National Gallery of Australia Travelling Exhibition The National Gallery of Australia is an Australian Government agency nga.gov.au/NIAT07 Sculpture Gallery • rOBERT rauSchenBerG • Ocean tO OutBack OC E A N to OUTBACK Australian landscape painting 1850 –1950 The National Gallery of Australia’s 25th Anniversary Travelling Exhibition 1 September 2007 – 27 January 2008 Proudly supported by the National Gallery of Australia Council Exhibition Fund National Gallery of Australia, Canberra This exhibition is supported by the CELEBRATING¬¬YEARS nga.gov.au/Rauschenberg Embassy of the United States of America Russell Drysdale Emus in a landscape 1950 (detail) oil on canvas National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Estate of Russell Drysdale Robert Rauschenberg Publicon – Station I from the Publicons series enamel on wood, collaged laminated silk and cotton, gold leafed paddle, light bulb, perspex, enamel on polished aluminium National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 1979 © Robert Rauschenberg Licensed by VAGA and VISCOPY, Australia, 2007 The National Gallery of Australia is an Australian Government agency artonview contents 2 Director’s foreword -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Temple Mount Faithful – Amutah Et Al V

Catholic University Law Review Volume 45 Issue 3 Spring 1996 Article 18 1996 Temple Mount Faithful – Amutah Et Al v. Attorney-General, Inspector-General of the Police, Mayor of Jerusalem, Minister of Education and Culture, Director of the Antiquities Division, Muslim WAQF - In the Supreme Court Sitting as the High Court of Justice [September 23, 1993] Menachem Elon Aharon Barak Gavriel Bach Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Menachem Elon, Aharon Barak & Gavriel Bach, Temple Mount Faithful – Amutah Et Al v. Attorney-General, Inspector-General of the Police, Mayor of Jerusalem, Minister of Education and Culture, Director of the Antiquities Division, Muslim WAQF - In the Supreme Court Sitting as the High Court of Justice [September 23, 1993], 45 Cath. U. L. Rev. 866 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol45/iss3/18 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Catholic University Law Review [Vol. 45:861 TEMPLE MOUNT FAITHFUL-AMUTAH ET AL. v. ATTORNEY-GENERAL INSPECTOR-GENERAL OF THE POLICE MAYOR OF JERUSALEM MINISTER OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE DIRECTOR OF THE ANTIQUITIES DIVISION MUSLIM WAQF In the Supreme Court Sitting as the High Court of Justice [September 23, 1993] Justice Menachem Elon, Deputy President, Justice Aharon Barak, Justice Gavriel Bach V. THE PARTIES Petitioners Petitioner 1: Temple Mount Faithful Amutah Petitioner 2: Chairman, Temple Mount Faithful Amutah Petitioners 3, 4, 5, 6: Members of Temple Mount Faithful Amutah Respondents Respondent 1: Attorney-General Respondent 2: Inspector-General of the Jerusalem Police Respondent 3: Mayor of Jerusalem Respondent 4: Minister of Education and Culture Respondent 5: Director of the Antiquities Division Respondent 6: Muslim Waqf Petition for an order nisi. -

(Eds.) Wittgenstein and the Philosophy of Information

Alois Pichler, Herbert Hrachovec (Eds.) Wittgenstein and the Philosophy of Information Publications of the Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society. New Series Volume 6 Alois Pichler • Herbert Hrachovec (Eds.) Wittgenstein and the Philosophy of Information Proceedings of the 30. International Ludwig Wittgenstein Symposium Kirchberg am Wechsel, Austria 2007 Volume 1 Bibliographic information published by Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de Gedruckt mit Förderung des Bundesministeriums für Wissenschaft und Forschung in Wien und der Kulturabteilung der NÖ Landesregierung North and South America by Transaction Books Rutgers University Piscataway, NJ 08854-8042 [email protected] United Kingdom, Ire, Iceland, Turkey, Malta, Portugal by Gazelle Books Services Limited White Cross Mills Hightown LANCASTER, LA1 4XS [email protected] Livraison pour la France et la Belgique: Librairie Philosophique J.Vrin 6, place de la Sorbonne ; F-75005 PARIS Tel. +33 (0)1 43 54 03 47 ; Fax +33 (0)1 43 54 48 18 www.vrin.fr 2008 ontos verlag P.O. Box 15 41, D-63133 Heusenstamm www.ontosverlag.com ISBN 978-3-86838-001-9 2008 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use of the purchaser of the work Printed on acid-free paper ISO-Norm 970-6 FSC-certified (Forest Stewardship Council) This hardcover binding meets the International Library standard Printed in Germany by buch bücher dd ag Table of Contents Preface Alois Pichler and Herbert Hrachovec . -

AP English Literature & Composition

01_194256 ffirs.qxp 12/13/07 1:03 PM Page i AP English Literature & Composition FOR DUMmIES‰ by Geraldine Woods 01_194256 ffirs.qxp 12/13/07 1:03 PM Page ii AP English Literature & Composition For Dummies® Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2008 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317-572-3447, fax 317-572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. AP is a registered trademark of The College Board. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

BZA Public Hearing of November 14, 2018

1 GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA + + + + + BOARD OF ZONING ADJUSTMENT + + + + + PUBLIC HEARING + + + + + WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 14, 2018 + + + + + The Regular Public Hearing convened in the Jerrily R. Kress Memorial Hearing Room, Room 220 South, 441 4th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C., 20001, pursuant to notice at 9:30 a.m., Frederick Hill, Chairperson, presiding. BOARD OF ZONING ADJUSTMENT MEMBERS PRESENT: FREDERICK L. HILL, Chairperson LESYLLEE M. WHITE, Board Member LORNA JOHN, Board Member CARLTON HART, Vice Chairperson (NCPC) ZONING COMMISSION MEMBER PRESENT: ROBERT MILLER OFFICE OF ZONING STAFF PRESENT: ALLISON MYERS, Secretary CLIFFORD MOY, Secretary STEPHEN VARGA, Zoning Specialist D.C. OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL PRESENT: JACOB RITTING, ESQ. NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVE., N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-3701 www.nealrgross.com 2 OFFICE OF PLANNING STAFF PRESENT: JOEL LAWSON JONATHAN KIRSCHENBAUM KAREN THOMAS MAXINE BROWN-ROBERTS CRYSTAL MEYERS The transcript constitutes the minutes from the Public Hearing held on November 14, 2018. NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVE., N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-3701 www.nealrgross.com 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY MATTERS Application No. 19862 of Heights Holding, LLC Postponed to December 5, 2018 .......... 9 Application No. 19851 of RUPSHA 2011, LLC, Postponed to December 19, 2018 ......... 9 APPLICATIONS ON AGENDA Application No. 19863 of KSAR LLC to permit a fast food restaurant use in the existing mixed use building in the NC8 Zone of premises 850 Quincy Street NW, Square 2900, Lot 824 . 11 Presentation by Alex Wilson .......... -

APSE-2014-Conference-Program-6 16 14.Pdf

Empower excluded populations—in your community and around the world. After taking a class with the School for Global Inclusion, I can say that “ the curriculum is more important now than ever. Students will learn to be leaders in their communities and graduate ready to develop solutions to problems concerning health, education, poverty, and disability across diverse populations and cultures. —Betsy Hopkins Director, Maine Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Introducing the School for Global Inclusion and Social Development A NEW KIND OF SCHOOL FOR A NEW KIND OF WORLD www.umb.edu/globalinclusion • [email protected] • 617.287.3070 Table of Contents The Naonal APSE Conference 2014 APSE Naonal Conference, Long Beach, CA Program has gone Mobile! 2 Leer from the Board President and Execuve Director 3 APSE Gold Members 4 Every Member Counts Fundraising Campaign 5 Sponsors 6 Chapter Sponsors 7 Welcome New Board Members 8 Naonal APSE Award Nominees 9 APSE Annual Raffle 10 Naonal APSE Execuve and Foundaon Board Members 11 Naonal Conference Commiee Volunteers 12 Real Stories Project 13 Hya Regency Hotel Floor Plan 15 Conference At-A-Glance 19 Keynote Speakers 21 Exhibitors 27 Chapter Presidents Access your free 30 Lead Presenters App by scanning 39 Tuesday Concurrent Presentaons the QR Code below 40 Students for APSE Track with your 66 Wednesday Concurrent Presentaons smartphone 82 Thursday Concurrent Presentaons 87 Downtown Long Beach Restaurants 1 2014 A Letter From the Executive Director and Board President Welcome to the 25th Annual National APSE Conference in sunny Long Beach, California, where our theme is Livin’ the dream…building the future for Employment First! Last year we celebrated the 25th anniversary of APSE, this year we celebrate our 25th conference so we hope you enjoy the sun, waves and networking this year. -

Midland Mirror

MIDLAND MIRROR Vol. LXXXIV MIDLAND SCHOOL LOS OLIVOS, CALIFORNIA 93441-0008 FEB 2016 NO. 1 Upper Yard Unites By Will Graham, Head of School, and Graham Mills, ‘16 hroughout January, several Tmoderate rain storms hit the campus, but we have yet to experience a real drought buster. Thanks to an improved drainage system, rain water is more evenly conveyed in the yards, and the campus appears to be dryer, cleaner, and safer. Time will tell, and we do expect to be tested if heavier rains arrive in the months to come. The prolonged drought has weakened the root structures of several trees; four have fallen among our buildings over the last year. We regularly monitor the limbs high overhead, and branches in the canopy are pruned frequently during the summer months and school breaks Ranch Manager Nick Tranmer and Graceson Aufderheide, ‘16, inspect fallen tree from behind caution-tape line. in order to lighten the load. On Thursday night, January 7, a large black locust tree (Robina As one would imagine, I was a bit startled. This was not pseudoacacia, a native to the eastern United States and most exactly regular small talk, so I hurried over in the pitch often used in making pallets) crashed down on a cabin roof in black to assess the situation. A few faculty, Kyle and Roddy Upper Yard, uprooting and rupturing a water line to a nearby Taylor, Celeste Carlisle, and Steve Sadro, were already there. fire hydrant. Lapmasters on duty quickly isolated the line and I could see immediately what Jack meant. -

Worship and Devotions

License, Copyright and Online Permission Statement Copyright © 2018 by Chalice Press. Outlines developed by an Editorial Advisory Team of outdoor ministry leaders representing six mainline Protestant denominations. Purchase of this resource gives license for its use, adaptation, and copying for programmatic use at one outdoor ministry or day camp core facility/operation (hereinafter, “FACILITY”) for up to one year from purchase. Governing bodies that own and operate more than one FACILITY must buy one copy of the resource for each FACILITY using the resource. Copies of the files may be made for use only within each FACILITY for staff and volunteer use only. Each FACILITY’s one-year permission now includes the use of this material for one year at up to three additional venues to expand the FACILITY’s reach into the local community. Examples would include offering outdoor ministry experiences at churches, schools, or community parks that are not part of your core FACILITY program. Copies of the files are for programming use only by staff and volunteers, and distribution for resale is strictly prohibited in any form electronically or in hard copy such as printing, copying, website posting/re-posting, emails, etc. Use of sí se puede® is by permission from United Farmworkers Union and Cesar Chavez Foundation. Use of this phrase outside of camp activities is not covered by this purchase and must be negotiated directly with UFW. Use of “May Peace Prevail on Earth” is by permission from World Peace Prayer Society. It can be freely used to promote peace but not for any commercial venture. -

Diverse Minds North State Journal 2017

© 2017 Published by Iversen Wellness & Recovery Center and Med Clinic 492 Rio Lindo Ave. Chico, CA 95926 (530) 879-3311 Iversen (530) 879-3974 Med Clinic [email protected] The Iversen Center is a program of Northern Valley Catholic Social Service, and is supported by Butte County Department of Behavioral Health and MHSA funding. ii Introduction Welcome to Diverse Minds North State Journal – a collection of writing and art from people across sixteen counties in Northern California who live a life of wellness and recovery from mental health challenges. What started as a simple idea – to put together packets of writing from members of our wellness center – became bigger than imagined. The Iversen Journal 2015 surpassed expectations and became a 60-page anthology of skilled writing along with advanced and creative art, proving what we knew all along – people can struggle with mental health challenges AND do amazing things. However, the Journal did something else as well. The Iversen Journal showed people that they were important, that they were valued members of this society and a part of a community that cares about them. Carrying that forward, the Iversen Journal 2016 was even bigger with 65 entries and 80 pages. The publication reached even further into the community-at-large and people started to notice. The stories throughout struck a tone and spoke out proudly about the lives and colors of the Iversen Center network of friends. Meanwhile, the Diverse Minds Film Festival came about. Students and individuals from Northern California were invited to create and submit films made that related to mental health topics. -

March 29-31, 2012

March 29-31, 2012 For up-to-the-minute scheduling changes, visit our mobile site at http://m.weber.edu/ncur2012 visitǤ email̷Ǥor Journal of Young Investigators ơ Ǥ • More than 750 articles and manuscripts published since 1997 • Represented in more than 10 countries and 50 academic institutions • Featured in Nature magazine, New York Times and Science magazine ơ Ǩ ǡǡ Ǥ Ǩ Photo: “Old School Light Bulb” by Joi Ito Table of Contents Contents Oral Session 2.........................................60 Oral Session 3.........................................67 Schedule of Events......................................3 Oral Session 4.........................................74 A Message from the President....................5 Oral Session 5.........................................81 NCUR Information......................................6 Oral Session 6.........................................86 NCUR Oversight Committee.......................7 Oral Session 7.........................................92 Acknowledgements...................................8 Oral Session 8.........................................98 Information Technology Services............10 Oral Session 10.....................................103 General Information.................................13 Poster Session Map.................................106 Plenary Speakers......................................17 Poster Sessions Sustainability.........................................20 Poster Session 1...................................107 Office of Undergraduate Research..........26