Days of the Colonists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

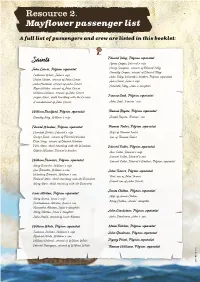

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

Girls on the Mayflower

Girls on the Mayflower http://members.aol.com/calebj/girls.html (out of circulation; see: https://www.prettytough.com/girls-on-the-mayflower/ http://mayflowerhistory.com/girls https://itchyfish.com/oceanus-hopkins-the-child-born-aboard-the-mayflower/ ) While much attention is focused on the men who came on the Mayflower, few people realize and take note that there were eleven girls on board, ranging in ages from less than a year old up to about sixteen or seventeen. William Bradford wrote that one of the Pilgrim's primary concerns was that the "weak bodies" of the women and girls would not be able to handle such a long voyage at sea, and the harsh life involved in establishing a new colony. For this reason, many girls were left behind, to be sent for later after the Colony had been established. Some of the daughters left behind include Fear Brewster (age 14), Mary Warren (10), Anna Warren (8), Sarah Warren (6), Elizabeth Warren (4), Abigail Warren (2), Jane Cooke (8), Hester Cooke (1), Mary Priest (7), Sarah Priest (5), and Elizabeth and Margaret Rogers. As it would turn out however, the girls had the strongest bodies of them all. No girls died on the Mayflower's voyage, but one man and one boy did. And the terrible first winter, twenty-five men (50%) and eight boys (36%) got sick and died, compared to only two girls (16%). So who were these girls? One of them was under the age of one, named Humility Cooper. Her father had died, and her mother was unable to support her; so she was sent with her aunt and uncle on the Mayflower. -

Utopian Promise

Unit 3 UTOPIAN PROMISE Puritan and Quaker Utopian Visions 1620–1750 Authors and Works spiritual decline while at the same time reaffirming the community’s identity and promise? Featured in the Video: I How did the Puritans use typology to under- John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity” (ser- stand and justify their experiences in the world? mon) and The Journal of John Winthrop (journal) I How did the image of America as a “vast and Mary Rowlandson, A Narrative of the Captivity and unpeopled country” shape European immigrants’ Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (captivity attitudes and ideals? How did they deal with the fact narrative) that millions of Native Americans already inhabited William Penn, “Letter to the Lenni Lenapi Chiefs” the land that they had come over to claim? (letter) I How did the Puritans’ sense that they were liv- ing in the “end time” impact their culture? Why is Discussed in This Unit: apocalyptic imagery so prevalent in Puritan iconog- William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (history) raphy and literature? Thomas Morton, New English Canaan (satire) I What is plain style? What values and beliefs Anne Bradstreet, poems influenced the development of this mode of expres- Edward Taylor, poems sion? Sarah Kemble Knight, The Private Journal of a I Why has the jeremiad remained a central com- Journey from Boston to New York (travel narra- ponent of the rhetoric of American public life? tive) I How do Puritan and Quaker texts work to form John Woolman, The Journal of John Woolman (jour- enduring myths about America’s -

Recovering Jane Goodwin Austin

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-11-2015 "So Long as the Work is Done": Recovering Jane Goodwin Austin Kari Holloway Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Miller, Kari Holloway, ""So Long as the Work is Done": Recovering Jane Goodwin Austin." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/153 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SO LONG AS THE WORK IS DONE”: RECOVERING JANE GOODWIN AUSTIN by KARI HOLLOWAY MILLER Under the Direction of Janet Gabler-Hover, PhD ABSTRACT The American author Jane Goodwin Austin published 24 novels and numerous short stories in a variety of genres between 1859 and 1892. Austin’s most popular works focus on her Pilgrim ancestors, and she is often lauded as a notable scholar of Puritan history who carefully researched her subject matter; however, several of the most common myths about the Pilgrims seem to have originated in Austin’s fiction. As a writer who saw her work as her means of entering the public sphere and enacting social change, Austin championed women and religious diversity. The range of Austin’s oeuvre, her coterie of notable friendships, especially amongst New England elites, and her impact on American myth and culture make her worthy of in-depth scholarly study, yet, inexplicably, very little critical work exists on Austin. -

An Historical Account of the Old State House of Pennsylvania Now Known

r-He weLL read mason li""-I:~I=-•I cl••'ILei,=:-,•• Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Mayflower 187

Mayflower 187 The Pilgrims A strange group of religious dissenters called “Pilgrims” had fled England circa 1608 to escape persecution and had settled in Leyden, Holland. A decade later, distressed by the fact that their children were losing contact with their English traditions and unable to earn a decent living in Holland, they had decided to seek a place to live and worship as they pleased in the emptiness of the New World. They approached Sir Edwin Sandys seeking permission to establish a settlement within the London Company’s jurisdiction; and Sandys, while not sympathetic to their religious views, appreciated their inherent worth and saw to it that their wish was granted. The Pilgrims boarded the Speedwell and sailed from Delfthaven, Holland. They joined with friends who had embarked on the Mayflower at Southhampton and sailed for the New World on August 6, 1620. However, the Speedwell leaked badly and both ships returned to Plymouth. Eventually, the Speedwell was sold and on September 6, l620, the group of about a hundred set out on the Mayflower. Had the Mayflower reached its intended destination in Virginia, the Pilgrims might well have been soon forgotten. However, they had been carried far out of their way, and the ship touched America on the desolate northern end of Cape Cod Bay. Unwilling to remain longer at the mercy of storm-tossed December seas, the settlers decided to remain. Since they were outside the jurisdiction of the London Company, the group claimed to be free of all governmental control. Therefore, before going ashore, the Pilgrims drew up the Mayflower Compact. -

Finding Aid: English Origins Project

Finding Aid: English Origins Project Descriptive Summary Repository: Plimoth Plantation Archive Location: Plimoth Plantation Research Library Collection Title: English Origins Project Dates: 1983-1985 (roughly) Extent: 2 drawers in wide filing cabinet Preferred Citation: English Origins Project, 1983-1985, Plimoth Plantation Archive, Plimoth Plantation, Plymouth, MA Abstract: The English Origins Project consists of 126 folders of material. Material is broken into general project information, family research, and town/village research. Administrative Information Access Restrictions: Access to materials may be restricted based on their condition; consult the Archive for more information. Use Restrictions: Use of materials may be restricted based on their condition or copyright status; consult the Archives for more information. Acquisition Information: Plimoth Plantation Related Collections and Resources: TBD Historical Note The English Origins Project was a project undertaken by researchers from Plimoth Plantation in 1984. The project was funded by an NEH Grant. The goal of the project was to gather information from towns and communities in England where the early settlers of Plymouth Colony lived before they migrated to America. The hope was to gather information to help create training manuals for the interpreters at Plimoth Plantation so that they could more accurately portray the early settlers. Plimoth Plantation is a living history museum where the interpreters provide the bulk of the information and knowledge about the 17th century settlement to the guests therefore accurate portrayal is very important. This project greatly improved interpretation and continues to benefit both interpreters and guests of the museum to this day. The research focused on dialect, folklore, material culture, agriculture, architecture, and social history. -

Children on the Mayflower

PILGRIM HALL MUSEUM America’s Oldest Continuous Museum – Located in Historic Plymouth Massachusetts www.pilgrimhallmuseum.org CHILDREN ON THE MAYFLOWER How many children were on the Mayflower? This seems like an easy question but it is hard to answer! Let’s say we wanted to count every passenger on the ship who was 18 years of age or younger. To figure out how old a person was in 1620, when the Mayflower voyage took place, you would need to know their date of birth. In some cases, though, there just isn’t enough information! On this list, we’ve included passengers who were probably or possibly age 18 or less. Some children were traveling with their families. Others came over as servants or apprentices. Still others were wards, or children in the care of guardians. There are 35 young people on the list. Some of them may have been very close to adulthood, like the servant Dorothy (last name unknown), who was married in the early years of Plymouth Colony. The list also includes Will Butten. He was a youth who died during the voyage and never arrived to see land. This list includes very young children and even some babies! Oceanus Hopkins was born during the Mayflower’s voyage across the Atlantic. The baby was given his unusual name as a result. Another boy, Peregrine White, was born aboard the ship while it was anchored at Cape Cod harbor - his name means traveler or “pilgrim.” A good source for more information on Mayflower passengers is Caleb Johnson’s http://mayflowerhistory.com/mayflower- passenger-list. -

The Story of the Four White Sisterit and Their Husbands--Catherine and Governor John Carver, Bridget and Pastor John Robinson

THE BOOK OF WHITE ANCESTRY THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE WHITE FAMILY IN NOTTINGHAMSHIRE, HOLBND AND MASSACHUSETTS • .The Story of the Four White Sisterit and their Husbands--Catherine and Governor John Carver, Bridget and Pastor John Robinson, Jane and Randal1 Tickens, Frances and Francis Jessop-- and of William White, the Pilgrim of Leyden and Plymouth, Father of Resolved and Peregrine; With Notes on the Families of Robinson, Jessup, and of Thomas ~hite of Wey- mouth, Massachusetts. Compiled by DR. CARLYLE SNOW \ffiITE, 6 Petticoat Lane, Guilford, Connecticut. PART ONE: THE WHITE FAMILY IN ENGLAND AND HOLLAND. 1. THOMAS WHITE OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE. 1 2. THE DESCENDANTS OF THOMAS WHITZ. 5 (1) The Smith Family. (2) Catherine \-Jhite and Governor John Carver. (3) The Ancestry of the Jessup Family. 3. WILLIAM vJHITE, FATHER OF EE30LVED AND PEREGRINE. 7 4. THE WHITES OF STURTON LE STEEPLE IN NOTTINGHAHSHIRE. 8 5. JOHN ROBINSON AND BRIDGET \-JHITE. 11 6. THE FOUNDING OF THE SEPARATIST CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH. 13 7. THE PILGRIMS IN HOLLA.ND. 15 (1) Thomas White and the Separatists 15 of the West. (2) 11A Separated People." 16 8. THE 11MAYFLOWER, 11 1620. 21 (1) Roger White and Francis Jessop. 22 PART TWO: THE FOUNDING OF NEW ENGIAND. l. PURITAN DEMOCRACY .AND THE NEW ENOLA.ND WAY. 26 2. ~ORDS AND RELICS OF THE \-JHITE FA?m.Y • 33 (1) Relics or the 'White Family in Pilgrim Hall and &.sewhere. 35 (2) The Famous 1588 •Breeches Bible1 or William White. 36 3. SUSANNA vlHITE AND GOVERNOR EDWARD WINSLCW. 37 4. RESOLVED \-JHITE AND JUDITH VASSALL OF PLYMOUTH AND MARSHFIEID, MASS. -

Our Mayflower Connection to Stephen Hopkins

OUR MAYFLOWER CONNECTION TO STEPHEN HOPKINS Plymouth Rock by Gerald R. Steffy OUR MAYFLOWER CONNECTION TO STEPHEN HOPKINS by Gerald R. Steffy 6206 N. Hamilton Road Peoria, IL 61614 E-Mail: [email protected] Mayflower Compact 1620 Agreement Between the Settlers at New Plymouth : 1620 IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620. 2 DEDICATED TO Betty Lou, my wife Vicki, our daughter Jerry, our son Kristyn, our granddaughter Joshua, our grandson Copyright (c) 2006 by Gerald R. -

Colonial Possessions

Colonial Possessions Introduction Bible The early Plymouth colonists brought with them most of the Associated with William Bradford furnishings, clothing, tools and other items they would need In the collection of Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, MA in their new homes. A few of these belongings have been The English-language Bible originally created in Geneva, preserved and handed down within the family for generations. Switzerland in 1560, was a very popular version, with more Museums such as Pilgrim Hall in Plymouth now hold many than 150 editions. Commonly known as the Geneva Bible, of these objects. Here are some of the objects and houses this translation was the first to have the text divided into associated with early Plymouth colonists. verses as well as chapters. It also had explanatory notes in the Damask Napkin margins. This copy of the Geneva Bible, owned by Plymouth Associated with Richard Warren and Robert Bartlett Colony governor William Bradford, was printed in London In the collection of Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, MA in 1599. This damask napkin was passed down through generations of Sword Hilt Mayflower passenger Richard Warren’s descendants. It is now Associated with Edward Doty, Richard Warren and Edward on display in the Pilgrim Hall Museum. It measures three feet Winslow by two feet and depicts a scene in Amsterdam with buildings In the collection of the General Society of Mayflower and a bridge over a canal. One woman from each generation Descendants, Plymouth, MA signed the napkin as it was handed down through the family. This sword hilt of an English sword, made circa 1600, was Wooden Cup found in 1898 during an excavation of the Edward Winslow Associated with Isaac Allerton and Thomas Cushman House in Plymouth, now owned by the General Society of In the collection of Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, MA Mayflower Descendants. -

Family Histories: Ives and Allied Families Arthur S

Family Histories: Ives and Allied Families Arthur S. Ives 241 Cliff Ave. Pelham, N.Y. Re-typed into digital format in 2012 by Aleta Crawford, wife of Dr. James Crawford, great-grandson of Arthur Stanley Ives Arthur S. Ives: Family Histories 2 Index Surname Earliest Latest Named Married to Page Named Individual (number Individual of generations) Adams, John (1) to Celestia (9) Arthur Ives 24 Alden John(1) to Elizabeth (2) William Pabodie 38 Aldrich George (1) to Mattithiah (2) John Dunbar 40 Or Aldridge Allyn Robert (1) to Mary (2) Thomas Parke, Jr. 41 Andrews William (1) to Mary (5) Joseph Blakeslee 42 Atwater David (1) to Mary (3) Ebenezer Ives 45 Barker Edward (1) to Eunice (4) Capt. John Beadle 47 Barnes Thomas (1) to Deborah (3) Josiah Tuttle 50 Bassett William (1) to Hannah (5) Samuel Hitchcock 52 Beadle Samuel (1) to Eunice Amelia Julius Ives 59 (7) Benton Edward (1) to Mary (4) Samuel Thorpe 73 Bishop John (1) to Mary (2) George Hubbard 75 Blakeslee Samuel (1) to Merancy (6) Harry Beadle 76 Bliss Thomas (1) to Deliverance (3) David Perkins 104 Borden Richard (1) to Mary (2) John Cook 105 Bradley William (1) to Martha (2) Samuel Munson 107 Brockett John (1) to Abigail (2) John Paine 108 Buck Emanuell (1) to Elizabeth (4) Gideon Wright 109 Buck Henry (1) to Martha (2) Jonathan Deming 110 Burritt William (1) to Hannah (4) Titus Fowler 111 Bushnell Francis (1) to Elizabeth (3) Dea. William 112 Johnson Chauncey Charles (1) to Sarah (4) Israel Burritt 113 Churchill Josiah (1) to Elizabeth (2) Henry Buck 115 Churchill Josiah (1) to Sarah (2) Thomas Wickham 115 Clark John (1) to Sarah (4) Samuel Adams 116 Collier William (1) to Elizabeth (2) Constant 119 Southworth Collins Edward (1) to Sybil (2) Rev.