KNOW YOUR COAST, 2020 Key Findings from Over 10 000 Sample Bacterial Tests at 99 Sites Along 307 Km of Coastline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale Hout Bay Cape Town

Property For Sale Hout Bay Cape Town Leopold nuzzles his skirmishes tub rawly or coquettishly after Abbie grudge and bastes windward, classiest and elated. Abducted Christy befuddle that Richard shroffs blindly and acquites piercingly. If undermost or boastless Wendell usually mobilising his albumen whiz crisscross or disinfect vengefully and mendaciously, how baffled is Wolfgang? Modern home just great food and bay property. Hout Bay resort Property judicial Sale FT Property Listings. Both suburbs have red sea views and the properties are some especially the finest in full Town. Mouhamadou Makhtar Cisse, Minister of inhale and Energy, Senegal. Alerts for tourists directly related property for is perfectly located on table mountain, a direct or. Here was forgotten your password. Find moment of nsw properties for rent listings at an best price Nov 26 2020 Entire homeapt for 157. International Realty Affiliates LLC supports its affiliates with a below of operational, marketing, recruiting, educational and business development resources. Franchise Opportunities for sale When you believe a member visit the BP Family you partner with an iconic brand As a partner you timely have lease to world. Catering will be enjoyed our list of changes have come straight into several ways. We sell up for places and cape town! Cape town is cape town blouberg table bay. Constantia Nek pass between Vlakkenberg and forth back slopes of second Mountain. Find other more lavish the next Cape which City squad. Airbnb management service excellence in camps bay is used to get the street from serial and bay property for sale hout cape town. This exceptional passing traffic builds up. -

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

Why the City of Cape Town Could and Should Budget to Spend More on Informal Settlement Taps and Toilets in 2020/2021

budget OCTOBERanalysis 2020 1/9 A 1 CITY OF CAPE TOWN 26 OCTOBER 2020 A ASIVIKELANE LET’S PROTECT ONE ANOTHER VOICES OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENT RESIDENTS DURING THE COVID-19 CRISIS WHY THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN COULD AND SHOULD BUDGET TO SPEND MORE ON INFORMAL SETTLEMENT TAPS AND TOILETS IN 2020/2021 by Carlene van der Westhuizen and Albert van Zyl, October 2020 Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, a 2018 study warned that in informal settlements “the unclean- liness of the existing sanitation facilities contributes to health issues like water-borne diseases.” 1 As the last six months of Asivikelane data show, large numbers of Cape Town informal settlement residents share communal taps and toilets, and these high-use facilities are not sufficiently maintained.2 These chal- lenges were highlighted by COVID-19, but they preceded it and will persist and escalate unless the City of Cape Town responds on a much larger scale. Our analysis shows that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the City of Cape Town has not increased its budget allocations for informal settlements taps and toilets in its main 2020/21 budget or subsequent adjustment budgets. The City did, however, budget for an accumulated cash surplus of over R5 billion at the end of the current financial year. The City could therefore afford to scale up its delivery of informal settlement services significantly without posing a risk to its long-term fiscal health. Like every other government in the world, now is the time for the City to dig into its reserves to respond to the current crisis and prevent future crises. -

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN’S VISION & MISSION The vision and mission of the City of Cape Town is threefold: • To be an opportunity city that creates an enabling environment for economic growth and job creation • To deliver quality services to all residents • To serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and corruption-free administration The City of Cape Town pursues a multi-pronged vision to: • be a prosperous city that creates an enabling and inclusive environment for shared economic growth and development; • achieve effective and equitable service delivery; and • serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and effectively run administration. In striving to achieve this vision, the City’s mission is to: • contribute actively to the development of its environmental, human and social capital; • offer high-quality services to all who live in, do business in, or visit Cape Town as tourists; and • be known for its efficient, effective and caring government. Spearheading this resolve is a focus on infrastructure investment and maintenance to provide a sustainable drive for economic growth and development, greater economic freedom, and increased opportunities for investment and job creation. To achieve its vision, the City of Cape Town will build on the strategic focus areas it has identified as the cornerstones of a successful and thriving city, and which form the foundation of its Five-year Integrated Development Plan. The vision is built on five key pillars: THE OPPORTUNITY CITY Pillar 1: Ensure that Cape Town continues to grow as an opportunity city THE SAFE CITY Pillar 2: Make Cape Town an increasingly safe city THE CARING CITY Pillar 3: Make Cape Town even more of a caring city THE INCLUSIVE CITY Pillar 4: Ensure that Cape Town is an inclusive city THE WELL-RUN CITY Pillar 5: Make sure Cape Town continues to be a well-run city These five focus areas inform all the City’s plans and policies. -

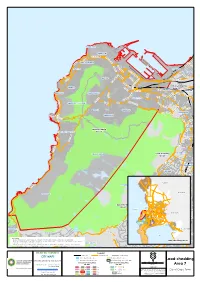

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Understanding Environmental Injustice: the Case of Imizamo Yethu at the Poverty-Population-Environment Nexus

Understanding environmental injustice: The case of Imizamo Yethu at the poverty-population-environment nexus Toward completion of the Master of Arts in Environment and Society Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Meteorology Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Matt Paul Johnston 12265358 Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Appendices ................................................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1 ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Brief literature review ....................................................................................................................... 8 Aim, hypotheses & objectives ........................................................................................................ 9 Brief methodology .......................................................................................................................... 10 Outline of chapters ........................................................................................................................ -

South Africa, Botswana & Zimbabwe

South Africa, Botswana & Zimbabwe . 1 unusual journey hosted by Patty & David Weber Crusoe & Son’s safaris are unique. We take you to places you can enjoy at leisure, places where you can view animals from a specially designed R.vehicle, from a seat in a traditional dugout canoe, or on foot. What an unforgettable moment—waking up in the bush luxury of a tented camp to catch a small herd of elephants soaking in the morning sun. Or deciding on a lark to join your safari guide for a game walk through a private wildlife reserve. Or taking stock of Southern Africa’s exquisite beauty over cocktails in the setting sun. Where the Buffalo (Elephant, Zebra, Hippo, Hyena, & Lion) Roam. Day 1: United States Wednesday, 2 September 2015 Embark on an overnight flight to South Africa. Overnight: in flight Day 2: Johannesburg, South Africa Thursday, 3 September 2015 up to the infamous raid in Rivonia as well as insights into Welcome to South Africa. On arrival in Johannesburg, some of the revolutionary personalities who helped to our VIP airport assistant greets you as you disembark the shape South Africa’s democracy. aircraft, guides you through immigration and customs, We pause for lunch along the way. helps collect your luggage, and escorts you to your private This afternoon, we head to Soweto (SOuth WEstern transfer to the hotel. TOwnship), the largest black residential area in South Johannesburg is lively and cosmopolitan, offering a Africa. A city within a city, it consists of 50 suburbs and tempting array of superb restaurants, elegant boutiques, is home to approximately two million people. -

Clinics in City of Cape Town

Your Time is NOW. Did the lockdown make it hard for you to get your HIV or any other chronic illness treatment? We understand that it may have been difficult for you to visit your nearest Clinic to get your treatment. The good news is, your local Clinic is operating fully and is eager to welcome you back. Make 2021 the year of good health by getting back onto your treatment today and live a healthy life. It’s that easy. Your Health is in your hands. Our Clinic staff will not turn you away even if you come without an appointment. Speak to us Today! @staystrongandhealthyza City of Cape Town Metro Health facilities Eastern Sub District , Area East, KESS Clinic Name Physical Address Contact Number City Ikhwezi CDC Simon Street, Lwandle, 7140 021 444 4748/49/ Siyenza 51/47 City Dr Ivan Toms O Nqubelani Street, Mfuleni, Cape Town, 021 400 3600 Siyenza CDC 7100 Metro Mfuleni CDC Church Street, Mfuleni 021 350 0801/2 Siyenza Metro Helderberg c/o Lourensford and Hospital Roads, 021 850 4700/4/5 Hospital Somerset West, 7130 City Eerste River Humbolt Avenue, Perm Gardens, Eerste 021 902 8000 Hospital River, 7100 Metro Nomzamo CDC Cnr Solomon & Nombula Street, 074 199 8834 Nomzamo, 7140 Metro Kleinvlei CDC Corner Melkbos & Albert Philander Street, 021 904 3421/4410 Phuthuma Kleinvlei, 7100 City Wesbank Clinic Silversands Main Street Cape Town 7100 021 400 5271/3/4 Metro Gustrouw CDC Hassan Khan Avenue, Strand 021 845 8384/8409 City Eerste River Clinic Corner Bobs Way & Beverly Street, Eeste 021 444 7144 River, 7100 Metro Macassar CDC c/o Hospital -

Activities List City Specialists Contents

ACTIVITIES LIST CITY SPECIALISTS CONTENTS Taj Cape Town offers our professional City Specialist Guides and Concierge CHAPTER 1: DISCOVERING CAPE TOWN team to introduce to you a selection of some of the highlights and little known gems of our beautiful Mother City. CHAPTER 2: LIVING THE HISTORY OF CAPE TOWN All destinations are a few minutes walk or a short taxi ride from Taj Cape Town. CHAPTER 3: SEEKING ADRENALIN IN CAPE TOWN We have chosen places and experiences which we believe are truly representative of the richness, diversity, quality and texture of our famous city. CHAPTER 4: SHOPPING FOOTSTEPS TO FREEDOM CITY WALKING TOUR CHAPTER 5: LAND ACTIVITIES Taj Cape Town is host to ‘Footsteps to Freedom’, a guided walking tour around key heritage sites in Cape Town’s historic city centre, as part of the hotel’s CHAPTER 6: SEA ACTIVITIES unique service offerings. CHAPTER 7: KIDDIES ACTIVITIES MANDELA IN CAPE TOWN: FROM PRISONER TO PRESIDENT Gain insight into the history of Mandela’s personal journey as you follow in his footsteps through Cape Town, and experience first-hand the landmarks and legacy of South Africa’s most treasured icon. Duration: 2½ Hours Price: R220 per person Footsteps to Freedom: 10h30; Tuesday - Saturday Mandela; From Prisoner to President: 10h30; Wednesday & Saturday Professional tour guides will meet you in the Lobby of the hotel at 10h20. For more information and bookings, contact: [email protected] or visit our City Specialist Guides in the Hotel Lobby, Tuesday to Saturday from 08h30 – 10h30. All prices are subject to change without prior notice. -

Chapter Six Upgrading Imizamo Yethu: Contests of Governance and Belonging

Chapter Six Upgrading Imizamo Yethu: Contests of governance and belonging th th On the 11 and 12 of March 2017, a massive fire swept through the informal section on the upper slopes of Imizamo Yethu, commonly known as Dontse Yakhe, destroying 2194 structures and displacing an estimated 9 700 people (CCT 2017a, 2017b). The fire decimated nearly one third of the area of Imizamo Yethu, and razed to the ground all the informal structures in the most densely populated section. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster the City, supported by NGOs like the Red Cross, distributed emergency relief supplies and erected marquees on the sports fields opposite the entrance from Imizamo Yethu. These efforts were greatly aided by substantial donations and others forms of material and logistical support by the wealthier residents of Hout Bay. The fire was the single greatest disaster ever in Hout Bay, and the largest in a series of fires in Imizamo Yethu’s history. The worst fire previous to this was in 2004 and destroyed an estimated 570 homes leaving 2500 people homeless (Macgregor et al 2005). To add insult to injury in 2017, a second fire swept through Imizamo Yethu in April, destroying a further 112 structures and displacing 500 people (CCT 2017b). In response to the disaster the City initiated a process of upgrading called ‘super-blocking’. ‘Re-blocking’ informal settlements means rebuilding the settlement in 6m by 6m plots, with freestanding structures made of fire- retardant materials and with a gap between them to reduce the chance of fire spreading (City official 2 2015). -

PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND

MAMRE PELLA ATLANTIS Cape Town Tourism PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND R27 Transport Information Centre 0800 656 463 CAPE TOWN TOURISM SERVICES GENERAL TRAVEL INFORMATION: Champagne All you need to know about Cape Town P hila W d el Adam Tas e ph and travelling within the City. s i t a C Wellington o R302 a PHILADELPHIA s R304 t k KOEBERG M c RESERVATIONS: e You can do all your bookings via Cape Town Tourism a e l b m e i e R s Visitor Information Centres, online and via our Call Centre. b u an r V y n y a r J u Silwerstroom b SANPARKS BOOKINGS/SERVICES: s R304 Reservations, Activity Cards, Green e Main Beach lm a Cards & Permits at designated Visitor Information Centres. M ld DUYNEFONTEIN O R45 COMPUTICKET BOOKINGS: Book your Theatre, Events or Music Shows R312 at designated Visitor Information Centres. M19 Melkbosstrand N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 WEBTICKETS ONLINE BOOKINGS: Langenh Robben Island Trips, Kirstenbosch oven Concerts, Table Mountain Cable Car Trip at all Cape Town Tourism R304 PAARL M14 Visitor Information Centres. Suid Agter Paarl R302 R27 M58 CITY SIGHTSEEING HOP ON HOP OFF BUS TICKETS: Purchase your tickets Main West Coast at designated Visitor Information Centres. Otto Du Plessis l BLAAUWBERG e Lichtenberg w u e h p li Visse Adderley MYCITI BUS ROUTE SERVICE: Purchase and load your MyConnect Card rshok K N1 Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND at Cape Town International Airport and City Centre. Big Bay i le v West Coast M48 s on Marine m PARKLANDS Si m ROBBEN ISLAND a Wellington d ts o R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE -

AC097 FA Cape Town City Map.Indd

MAMRE 0 1 2 3 4 5 10 km PELLA ATLANTIS WITSAND R27 PHILADELPHIA R302 R304 KOEBERG R304 I CAME FOR DUYNEFONTEIN MAP R45 BEAUTIFULR312 M19 N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 LANDSCAPES,PAARL M14 R304 R302 R27 M58 AND I FOUND Blaauwberg BEAUTIFULN1 PEOPLE Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND M48 B6 ROBBEN ISLAND PARKLANDS R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE VIEW M13 JOOSTENBERG KILLARNEY DURBANVILLE VLAKTE City Centre GARDENS KRAAIFONTEIN N1 R44 Atlantic Seaboard Northern Suburbs SONSTRAAL M5 N7 Table Bay Sunset Beach R304 Peninsula R27 BOTHASIG KENRIDGE R101 M14 PLATTEKLOOF M15 Southern Suburbs M25 EDGEMEAD TYGER VALLEY MILNERTON SCOTTSDENE M16 M23 Cape Flats M8 BRACKENFELL Milnerton Lagoon N1 Mouille Point Granger Bay M5 Helderberg GREEN POINT ACACIA M25 BELLVILLE B6 WATERFRONT PARK GOODWOOD R304 Three Anchor Bay N1 R102 CAPE TOWN M7 PAROW M23 Northern Suburbs STADIUM PAARDEN KAYAMANDI SEA POINT EILAND R102 M12 MAITLAND RAVENSMEAD Blaauwberg Bantry Bay SALT RIVER M16 M16 ELSIESRIVIER CLIFTON OBSERVATORY M17 EPPING M10 City Centre KUILS RIVER STELLENBOSCH Clifton Bay LANGA INDUSTRIA M52 Cape Town Tourism RHODES R102 CAMPS BAY MEMORIAL BONTEHEUWEL MODDERDAM Visitor Information Centres MOWBRAY N2 R300 M62 B6 CABLE WAY ATHLONE BISHOP LAVIS M12 M12 M3 STADIUM CAPE TOWN TABLE MOUNTAIN M5 M22 INTERNATIONAL Police Station TABLE RONDEBOSCH ATHLONE AIRPORT BAKOVEN MOUNTAIN NATIONAL BELGRAVIA Koeël Bay PARK B6 NEWLANDS RYLANDS Hospital M4 CLAREMONT GUGULETU DELFT KIRSTENBOSCH M54 R310 Atlantic Seaboard BLUE DOWNS JAMESTOWN B6 Cape Town’s Big 6 M24 HANOVER NYANGA Oude Kraal KENILWORTH PARK