Australian Left Review No. 24 April-May 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly

Sara M. EvanS Women’s Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly Approximately fifty members of the five Chicago radical women’s groups met on Saturday, May 18, 1968, to hold a citywide conference. The main purposes of the conference were to create and strengthen ties among groups and individuals, to generate a heightened sense of common history and purpose, and to provoke imaginative pro- grammatic ideas and plans. In other words, the conference was an early step in the process of movement building. —Voice of Women’s Liberation Movement, June 19681 EvEry account of thE rE-EmErgEncE of feminism in the United States in the late twentieth century notes the ferment that took place in 1967 and 1968. The five groups meeting in Chicago in May 1968 had, for instance, flowered from what had been a single Chicago group just a year before. By the time of the conference in 1968, activists who used the term “women’s liberation” understood themselves to be building a movement. Embedded in national networks of student, civil rights, and antiwar movements, these activists were aware that sister women’s liber- ation groups were rapidly forming across the country. Yet despite some 1. Sarah Boyte (now Sara M. Evans, the author of this article), “from Chicago,” Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, June 1968, p. 7. I am grateful to Elizabeth Faue for serendipitously sending this document from the first newsletter of the women’s liberation movement created by Jo Freeman. 138 Feminist Studies 41, no. 1. © 2015 by Feminist Studies, Inc. Sara M. Evans 139 early work, including my own, the particular formation calling itself the women’s liberation movement has not been the focus of most scholar- ship on late twentieth-century feminism. -

The New Left

1 The New Left Key Political Leaders: Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, and Jerry Rubin (US); Daniel Cohn-Bendit (France); Rudi Dutschke, Joschka Fischer, Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof, and Fritz Teufel (Germany). Key Intellectuals Associated with the New Left: Herbert Marcuse, Wilhelm Reich, Alan Sillitoe, Guy Debord, E. P. Thompson, Erik Hobsbawm, Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, Ernst Bloch, C. Wright Mills, Marshall Berman, Isaac Deutscher, Erich Fromm. Rejection of the Old Left. The New Left represented a break with the orthodox Leninist-Stalinist communist movement of the 1920s and 1930s that had reached the apogee of its influence in the years right after World War II. Already in the 1940s, a few key communist intellectuals had come out against Soviet Communism as practiced under Stalin most famously, Arthur Koestler (whose Darkness at Noon was published in 1940) and George Orwell (as suggested by his 1945 novel Animal Farm and the 1949 novel 1984). The biggest blow to the influence of international communism came in 1956, when the Soviet invasion of Hungary made it increasingly difficult for communists to claim that communism had popular support in Eastern Europe. In the same year, the Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev had given his famous Cult of Personality Speech in which he denounced Stalin for his excessive use of violence and police power since the 1930s. Together, these events made many Leftists accept the fact that somewhere communism had taken a wrong turn in the Soviet Union. Marxist Revisionism. A few intellectuals rejected Marxism all together, but an influential group of Leftists tried to recapture the original intent of Karl Marx. -

Left of Karl Marx : the Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones / Carole Boyce Davies

T H E POLI T I C A L L I F E O F B L A C K C OMMUNIS T LEFT O F K A R L M A R X C L A U D I A JONES Carole Boyce Davies LEFT OF KARL MARX THE POLITICAL LIFE OF BLACK LEFT OF KARL MARX COMMUNIST CLAUDIA JONES Carole Boyce Davies Duke University Press Durham and London 2007 ∫ 2008 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Adobe Janson by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Preface xiii Chronology xxiii Introduction. Recovering the Radical Black Female Subject: Anti-Imperialism, Feminism, and Activism 1 1. Women’s Rights/Workers’ Rights/Anti-Imperialism: Challenging the Superexploitation of Black Working-Class Women 29 2. From ‘‘Half the World’’ to the Whole World: Journalism as Black Transnational Political Practice 69 3. Prison Blues: Literary Activism and a Poetry of Resistance 99 4. Deportation: The Other Politics of Diaspora, or ‘‘What is an ocean between us? We know how to build bridges.’’ 131 5. Carnival and Diaspora: Caribbean Community, Happiness, and Activism 167 6. Piece Work/Peace Work: Self-Construction versus State Repression 191 Notes 239 Bibliography 275 Index 295 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS his project owes everything to the spiritual guidance of Claudia Jones Therself with signs too many to identify. At every step of the way, she made her presence felt in ways so remarkable that only conversations with friends who understand the blurring that exists between the worlds which we inhabit could appreciate. -

The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 11:01 Labour Journal of Canadian Labour Studies Le Travail Revue d’Études Ouvrières Canadiennes The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A. Zumoff Volume 85, printemps 2020 Résumé de l'article Dans les premières années de la Grande Dépression, le Parti socialiste URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070907ar américain a attiré des jeunes et des intellectuels de gauche en même temps DOI : https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2020.0006 qu’il était confronté au défi de se distinguer du Parti démocrate de Franklin D. Roosevelt. En 1936, alors que sa direction historique de droite (la «vieille Aller au sommaire du numéro garde») quittait le Parti socialiste américain et que bon nombre des membres les plus à gauche du Parti socialiste américain avaient décampé, le parti a perdu de sa vigueur. Cet article examine les luttes internes au sein du Partie Éditeur(s) socialiste américain entre la vieille garde et les groupements «militants» de gauche et analyse la réaction des groupes à gauche du Parti socialiste Canadian Committee on Labour History américain, en particulier le Parti communiste pro-Moscou et les partisans de Trotsky et Boukharine qui ont été organisés en deux petits groupes, le Parti ISSN communiste (opposition) et le Parti des travailleurs. 0700-3862 (imprimé) 1911-4842 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Zumoff, J. (2020). The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935. Labour / Le Travail, 85, 165–198. -

American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2015 If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C. Kerley East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerley, Sarah C., "If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2614. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2614 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left —————————————— A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History —————————————— by Sarah Caitlin Kerley December 2015 —————————————— Dr. Elwood Watson, Chair Dr. Daryl A. Carter Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Folk Music, Communism, Radical Left ABSTRACT If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left by Sarah Caitlin Kerley Folk music is one of the most popular forms of music today; artists such as Mumford and Sons and the Carolina Chocolate Drops are giving new life to an age-old music. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series SOC2019-2637

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2014-1176 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series SOC2019- 2637 Corbyn’s Ideology: Social Democracy, Democratic Socialism, or Left Populism? Burak Cop Associate Professor Istanbul Kültür University Turkey 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: SOC2019-2637 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series Conference papers are research/policy papers written and presented by academics at one of ATINER‘s academic events. ATINER‘s association started to publish this conference paper series in 2012. All published conference papers go through an initial peer review aiming at disseminating and improving the ideas expressed in each work. Authors welcome comments Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research This paper should be cited as follows: Cop, B. (2018). “Corbyn’s Ideology: Social Democracy, Democratic Socialism, or Left Populism?”, Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: SOC2019-2637. Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN: 2241-2891 17/07/2019 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: SOC2019-2637 Corbyn’s Ideology: Social Democracy, Democratic Socialism, or Left Populism? Burak Cop Associate Professor Istanbul Kültür University Turkey Abstract The ―Third Way‖, the recipe Labour Party (UK) adopted in the 1990s with the aim to differ from the old left and the New Right and to reconcile the social democracy with the primacy of the market, was the consequence of the end of the Welfare State consensus, the decline of the Marxism‘s appeal, and the economic, social, and technological changes that took place after the 1970s in the capitalist world. -

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki's Karl Marx

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary By Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Dr. Harry Cleaver ________________________ Dr. Michael Jakobson ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo August 2008 An Abstract of Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Toledo August 2008 In 1966 the Japanese New Left thinker Yoshimoto Taka’aki published his seminal book on Karl Marx. The originality of this overview of Marx’s ideas and life lay in Yoshimoto’s stress on the young Marx’s theory of alienation as an outgrowth of a unique philosophy of nature, whose roots went back to the latter’s doctoral dissertation. It echoed Yoshimoto’s own reformulation of “alienation” (and Marx’s labor theory of value) as key concept in his theory of literary language (What is Beauty in Language), which he had just completed in 1965, and extended his argument -- ongoing from the mid-1950s -- with Japanese Marxism over questions of literature, politics, and culture. His extraction of the theme of “communal illusion” from the early Marx foregrounds his second major theoretical work of the decade, Communal Illusion, which he started to serialize in 1966 and completed in 1968, and outlines an important theoretical closure to the existential, political, and intellectual struggles he had waged since the end of the ii Pacific War. -

The New Left in the Sixties: Political Philosophy Or Philosophical Politics?

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 6, No. 4; August 2016 The New Left in the Sixties: Political Philosophy or Philosophical Politics? Frédéric ROBERT, PhD Assistant Professor of American Studies Université Jean Moulin-Lyon III France Abstract This paper analyzes what the New Left, a multi-faceted protest organization which emerged in the Sixties, was all about. It presents its slow evolution—from the Old Left to the New Left—its main organizations and the different stages it went through to become the main counter-power in the United States striving to transform American society. The paper also insists on the philosophical and political aspects which gave birth to the New Left, while showing to what extent it was different from the Old Left, mainly because it favored direct actions, deemed more effective by its members than time-consuming ideological debates. Introduction The fact that a New Left exists in the United States today (…) is the proof of a reality which manifests itself both in society at large and in the political arena. What this New Left is is more difficult to say, because there is very little unity between the various organizations, programs, and ideological statements which form the phenomenon usually referred to as ‘the Movement.’1 According to Massimo Teodori, a historian and political scientist, it is particularly difficult to understand the American New Left which emerged in the Sixties. It is even more complicated to analyze it. Paradoxically enough, it also found it difficult to analyze it because of the numerous strategic and ideological changes it went through. -

Libertarian Socialism

Libertarian Socialism PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 12 Aug 2012 19:52:27 UTC Contents Articles Libertarian socialism 1 The Venus Project 37 The Zeitgeist Movement 39 References Article Sources and Contributors 42 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 43 Article Licenses License 44 Libertarian socialism 1 Libertarian socialism Libertarian socialism (sometimes called social anarchism,[1][2] and sometimes left libertarianism)[3][4] is a group of political philosophies that promote a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic society without private property in the means of production. Libertarian socialists believe in converting present-day private productive property into the commons or public goods, while retaining respect for personal property[5]. Libertarian socialism is opposed to coercive forms of social organization. It promotes free association in place of government and opposes the social relations of capitalism, such as wage labor.[6] The term libertarian socialism is used by some socialists to differentiate their philosophy from state socialism[7][8] or by some as a synonym for left anarchism.[1][2][9] Adherents of libertarian socialism assert that a society based on freedom and equality can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control certain means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite.[10] Libertarian socialism also constitutes a tendency of thought that -

After the New Social Democracy Offers a Distinctive Contribution to Political Ideas

fitzpatrick cvr 8/8/03 11:10 AM Page 1 Social democracy has made a political comeback in recent years, After thenewsocialdemocracy especially under the influence of the Third Way. However, not everyone is convinced that this ‘new social democracy’ is the best means of reviving the Left’s social project. This book explains why and offers an alternative approach. Bringing together a range of social and political theories After the After the new new social democracy engages with some of the most important contemporary debates regarding the present direction and future of the Left. Drawing upon egalitarian, feminist and environmental social democracy ideas it proposes that the social democratic tradition can be renewed but only if the dominance of conservative ideas is challenged more effectively. It explores a number of issues with this aim in mind, including justice, the state, democracy, welfare reform, new technologies, future generations and the new genetics. Employing a lively and authoritative style After the new social democracy offers a distinctive contribution to political ideas. It will appeal to all of those interested in politics, philosophy, social policy and social studies. Social welfare for the Tony Fitzpatrick is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Sociology and Social twenty-first century Policy, University of Nottingham. FITZPATRICK TONY FITZPATRICK TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page i After the new social democracy TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page ii For my parents TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page iii After the new social democracy Social welfare for the twenty-first century TONY FITZPATRICK Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page iv Copyright © Tony Fitzpatrick 2003 The right of Tony Fitzpatrick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

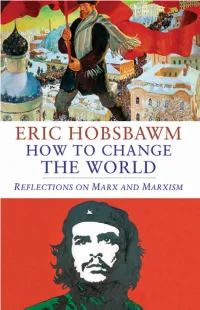

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm The Age of Revolution 1789–1848 The Age of Capital 1848–1875 The Age of Empire 1875–1914 The Age of Extremes 1914–1991 Labouring Men Industry and Empire Bandits Revolutionaries Worlds of Labour Nations and Nationalism Since 1780 On History Uncommon People The New Century Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism Interesting Times How to Change the World Reflections on Marx and Marxism Eric Hobsbawm New Haven & London To the memory of George Lichtheim This collection first published 2011 in the United States by Yale University Press and in Great Britain by Little, Brown. Copyright © 2011 by Eric Hobsbawm. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Typeset in Baskerville by M Rules. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927314 ISBN 978-0-300-17616-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Foreword vii PART I: MARX AND ENGELS 1 Marx Today 3 2 Marx,