HAZING, HEGEMONIC MASCULINITY, and VICTIMIZATION TONIQUA CHAREE MIKELL University of South Carolina - Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bystander Intervention Handout

WHAT IS HAZING? Based on the definition provided, when does an activity cross the line into hazing? The following three components of the hazing IS... definition of hazing are key to understanding hazing: “Hazing is any activity 1. Group context | Hazing is associated with the process of joining expected of someone and maintaining membership in a group. joining or participating 2. Abusive behavior | Hazing involves behaviors and activities that in a group that are potentially humiliating and degrading, with potential to cause humiliates, degrades, physical, psychological and/or emotional harm. abuses, or endangers 3. Regardless of an individual’s willingness to participate | The “choice” to participate in a hazing activity is deceptive because it’s them regardless of a person’s willingness to usually paired with peer pressure and coercive power dynamics that (Allan & Madden, 2008) are common in the process of gaining membership in some groups. participate.” Circumstances in which pressure or coercion exist can prevent true (Allan & Madden, 2008) consent. WHAT MIGHT HAZING LOOK LIKE? • Ingestion of vile substances or concoctions • Being awakened during the night by other members • Singing or chanting by yourself or with other members of a group in public in a situation that is not a related to an event, game, or practice • Demeaning skits • Associating with specific people and not others • Enduring harsh weather conditions without appropriate clothing • Being screamed, yelled, or cursed at by other • Drinking large amounts of alcohol to the point of members getting sick or passing out • Wearing clothing that is humiliating and not part • Sexual simulations or sex acts of a uniform • Sleep deprivation • Paddling or whipping • Water intoxication • Forced swimming REMEMBER: Hazing is not necessarily defined by a list of behaviors or activities. -

Assessing the Efficacy of Analytical Definitions in Hazing Education

Assessing the Efficacy of Analytical Definitions in Hazing Education by Paul Robert Kittle, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 8, 2012 Keywords: hazing, definition, cognitive, extensional, analytical, bystander Copyright 2012 by Paul Robert Kittle, Jr. Approved by David C. DiRamio, Chair, Associate Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology James E. Witte, Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology Maria Witte, Associate Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology Abstract Hazing is a problem that persists on college campuses and in high schools. According to Nuwer (2011) between 1970 and 2006, there was at least one hazing-related death each year on a college campus. Hazing education and prevention programs, such as speaker series, anti-hazing marketing campaigns, policy enforcement efforts, and sanctioning, which are frequently grounded in an extensional definition of hazing, have been present on college campuses for the past 20 years, yet the incidents of hazing are on the rise (Ellsworth, 2006; Nuwer, 2004). The literature repeatedly states that, due to the lack of a common definition, awareness and prevention efforts are often unsuccessful at increasing students’ awareness of hazing activities or reducing the likelihood that hazing activities will occur (Allan & Madden, 2008; Ellsworth, 2006; Hollmann, 2002; Shaw, 1992; Smith, 2009). Allan and Madden (2008) found that 91 percent of students who have experienced hazing do not identify themselves as being hazed. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether or not there were differences in students’ ability to identify hazing activities after treatment which consisted of reading either an extensional or analytical definition of hazing. -

Alumni Pass Resolution Pledging Themselves

NOW FOR NOW FOR BASKETBALL AND BASKETBALL AND EXAMS EXAMS Vol. VI WAKE FOREST, N. C., SATURDAY, JANUARY 10, 1925 No.14 I Demon Quint Wins ALUMNI PASS RESOLUTION PLEDGING SCHEDULE OF EXAMINATIONS First January 26-January 31 I Game of Year When They THEMSELVES ACTIVELY IN fAVOR OF 1 Morning-9: 00-12: 00 Afternoon-2: 00-5:00 Defeat Durham Elks 35-23 JANUARY 26 ------------------------·+ AGREATER WAKE FOREST COLLEGE All classes meeting fifth hour on \ All classes meeting second hour on Tuesdays. Tuesdays. Greason and Emmerson Highest JANUARY 27 l··-;;;;;;;·;;~;;;;··r Scorers, While Ober Plays Davidson County Alumni Start Alumnus Writes Of All classes meeting fourth hour on \ All classes meeting first hour on l i t Great Ball on Defense Ball Rolling at Annual Ban· Future Of College Tuesdays. Tuesdays. f !\1 iss l\Im·y .-\lice Holliday ex· I quet December 26th JANUARY 28 i pt·essecl lu•t•selt' us being very ~ S. G. Hasty, of Lexington, Tells All classes meeting sixth hour on IAll classes meeHng first hour on ! mu(•h pleased with her fit•st f EMMERSON AS A FORWARD Mondays. Mondays. f Chl'istnms on this !)lanet, and j of Needs of Wake Forest and PLAN FOR·CEN;TENNIAL JA1\'UARY 29 t belie,ves she is going to like it. - There is one flting she doesn't 1_ Daniels Starts at Center; Many Issues a Challenge All classes meeting thir(l hour on \ All classes meeting fifth hour on i = quite un<let·st.nnd, and that is ! Tuesdays. Mondays. • Substitutions in Lineup To Richmond Takes Same Action; WHAT 0 F THE FUTURE ? wh)· eve•·~·body should be sentl• I l JANUARY 30 i ing her Clu·istmus curds and i ward End of the Game All Want Machinery to 1 All classes meeting sixth hour on I All classes meeting fourth hour on 1 presents, and even be wt·it-ing = Tuesdays. -

January 16, 1989

tressing: Classes, activities get to students 14 THURSDAY, JANUARY 19, 1989 JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY VOL. 66 NO. 30 Sprint splash 'Scream' JMU population is getting too big By Wendy Warren staff writer A group of JMU students, angry about what they say is a threat to the university's identity, plans to fight what they consider uncontrolled enrollment growth. The Student Committee to Review Enrollment at Madison (Scream) wants to keep enrollment at a level JMU can handle, said founder Stephan Fogleman, who also is secretary of the Student Government Association. "The reason I chose JMU was that it was not too big and not too small," Fogleman said. "But [JMU] is real close to losing that attractive feature." The overcrowded conditions have made JMU impersonal, and "almost like a corporation now," he said. Scream's members consist of JMU sophomores and freshmen who are active in the Student Government Association, since "these arc the people who will Staff photo by LAWRENCE JACKSON have to deal with the enrollment issues," Fogleman A runner treks along JMU's rain-streaked track Sunday afternoon. said. Most seniors who are active in campus politics are too busy to solve JMU's long-term problems, he said. "It's what will happen over the next four years Students vary on hazing views that worries me." Within the next week, the group will circulate a petition against increasing JMU's current enrollment, By Rob Morano presented to about 45 greek organizations nationwide, assistant editorial editor he attempts to define hazing and its dangers. Fogleman said. -

PRESENTATION at TOWN HALL MEETING May 29, 2019 What

PRESENTATION AT TOWN HALL MEETING May 29, 2019 What follows are notes of the presentation made by Mr. Sandler on behalf of the SMCS Respect and Culture Review Committee at the opening of the town hall meeting on May 29, 2019. My name is Mark Sandler. I am the Chair of the SMCS Respect and Culture Review Committee. The other committee members are also here tonight. Dr. Debra Pepler is a Distinguished Research Professor of Psychology at York University, best known for her ongoing research on aggression, bullying and victimization involving children and adolescents. Priti Sachdeva is former legal counsel at the Office of the Children’s Lawyer whose practice focused on areas of law affecting children and other vulnerable people. Bruce Rodrigues is a former Deputy Minister of Education who has experience as a Director of Education for the Toronto Catholic District School Board, a teacher, principal and coach at the secondary school and university level I have been a lawyer for almost 40 years, serving as counsel on over 20 systemic reviews or public inquiries including two involving misconduct at schools and the development of best practices in the public and private school systems. Scott Bergman, counsel to the Committee, a highly experienced lawyer, and Naz Jaswal, our firm’s articling student are also present. Naz has contacted a number of you in connection with interviews we have conducted. 1 Thank you all for joining us tonight. It shows a deep commitment on the part of the St Michael’s community to the school and its success. And most importantly, to the undeniable goal of ensuring that students thrive in a safe and nurturing environment. -

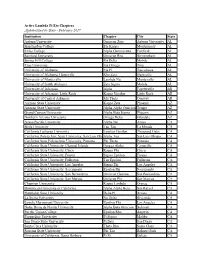

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State - February 2017 Institution Chapter City State Auburn University Omicron Zeta Auburn University AL Huntingdon College Eta Kappa Montgomery AL Miles College Alpha Gamma Iota Fairfield AL Samford University Omicron Rho Birmingham AL Spring Hill College Psi Delta Mobile AL Troy University Eta Omega Troy AL University of Alabama Eta Pi Tuscaloosa AL University of Alabama, Huntsville Rho Zeta Huntsville AL University of Montevallo Lambda Nu Montevallo AL University of South Alabama Zeta Sigma Mobile AL University of Arkansas Alpha Fayetteville AR University of Arkansas, Little Rock Kappa Upsilon Little Rock AR University of Central Arkansas Mu Theta Conway AR Arizona State University Kappa Zeta Phoenix AZ Arizona State University Alpha Alpha Omicron Tempe AZ Grand Canyon University Alpha Beta Sigma Phoenix AZ Northern Arizona University Omega Delta Glendale AZ Azusa Pacific University Alpha Nu Azusa CA Biola University Tau Tau La Mirada CA California Lutheran University Upsilon Upsilon Thousand Oaks CA California Polytechnic State University, San Luis ObispoAlpha Tau San Luis Obispo CA California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Phi Theta Pomona CA California State University, Channel Islands Omega Alpha Camarillo CA California State University, Chico Kappa Phi Chico CA California State University, Fresno Sigma Epsilon Fresno CA California State University, Fullerton Tau Epsilon Fullerton CA California State University, Los Angeles Sigma Phi Los Angeles CA California State University, -

Kindness Is Powerful. It Is More Powerful Than Hazing…It Is the Very Essence of Inclusion. and It Will Defeat Anti-Greek Se

“Kindness is powerful. It is more powerful than hazing…it is the very essence of inclusion. And it will defeat anti-greek sentiment.” - Fraternity President Kimberlee Di Fede Sullivan, Pepperdine OUR KIND OF KIND DOES NOT HAZE This resource was created to promote dialogue and encourage action in the area of hazing prevention. Collegiate members and advisors can review this document and use it to analyze the actions and behaviors in their chapter. Chapters are encouraged to share this resource with members before or after implementing a hazing prevention peer-led module to enhance their conversations about hazing. DEFINING HAZING In our policies, kindness is clear. Tri Delta has a zero-tolerance policy against hazing. Hazing may be the least kind thing you can do to another human being – let alone a brother or sister. Hazing is defined by the Fraternity as any action which may be interpreted as producing, in any member, new member or other individual, mental or physical discomfort, embarrassment, harassment or ridicule; or as any activity which sets members, new members or any other individuals apart from other members or from the chapter without a constructive purpose. Encouraging, coordinating and/or participating in a hazing activity, being a bystander and/or being subjected to hazing is prohibited regardless of location (on or off campus) and regardless of timing (e.g., during an academic term, during host institution closure for holiday or recess, etc.). RECOGNIZING HAZING We often hear hazing defined as extreme behaviors that we would not want to be associated with such as: • Physical violence • Binge drinking • Emotional or psychological abuse • Pranks • Illegal or harmful activities However, hazing is more than just a list of harmful behaviors. -

Publication.Pdf

1 Edited by the National Staff - Special thanks to: Daniel Miller ΑΦΖ '14 Nicolas R. Hewgley ΔΣΦ '15 The Exoteric Manual, 18th Edition, 2015 The Fraternity of Alpha Chi Rho 2 RB Stewart National Headquarters 109 Oxford Way Neptune, NJ 07753 [email protected] (E-Mail) (732) 869-1895 (Phone) www.alphachirho.org (Website) www.facebook.com/AlphaChiRhoHQ (Facebook) 3 "The experience of Greek letter societies has developed certain tendencies against which we need to caution ourselves and our younger brethren." The tendencies we should avoid include vanity, egotism, contempt for the poor, a merely social spirit, idleness, and inactivity. Revered Founder Rev. Paul Ziegler 4 INTRODUCTION The first Exoteric Manual was printed in 1895 under the authorship of Revered Founder Paul Ziegler. Designed to present the ideas of the Fraternity, the six paged, 3.5" x 4.5" book contained an oath for postulants encouraging them to maintain the high ideals of Alpha Chi Rho. Since 1895 the Exoteric Manual has been revised many times to reflect the growth and changes in the Fraternity. Though the manual has encountered changes, its purpose as an educational tool and Brotherhood life-guide has not. This Exoteric contains the history of Alpha Chi Rho, its principles, ideals and mission. As the men of Alpha Chi Rho, we must always keep an eye open to change and development. Since the inception, the Fraternity has gone through many changes which have enabled the Fraternity to survive. Evolution has made this Fraternity stronger and better able to fulfill the changing needs of the brotherhood. The new Exoteric Manual is a book for life and is to be used not only through the Postulant period, but also through one’s college career and beyond. -

Examples of Hazing Divided Into Three Categories: Subtle, Harassment, and Violent

The following are some examples of hazing divided into three categories: subtle, harassment, and violent. It is impossible to list all possible hazing behaviors because many are context-specific. While this is not an all-inclusive list, it provides some common examples of hazing traditions. More Examples. A. SUBTLE HAZING : Behaviors that emphasize a power imbalance between new members/rookies and other members of the group or team. Termed “subtle hazing” because these types of hazing are often taken-for-granted or accepted as “harmless” or meaningless. Subtle hazing typically involves activities or attitudes that breach reasonable standards of mutual respect and place new members/rookies on the receiving end of ridicule, embarrassment, and/or humiliation tactics. New members/rookies often feel the need to endure subtle hazing to feel like part of the group or team. (Some types of subtle hazing may also be considered harassment hazing). Some Examples: • Deception • Assigning demerits • Silence periods with implied threats for violation • Deprivation of privileges granted to other members • Requiring new members/rookies to perform duties not assigned to other members • Socially isolating new members/rookies • Line-ups and Drills/Tests on meaningless information • Name calling • Requiring new members/rookies to refer to other members with titles (e.g. “Mr.,” “Miss”) while they are identified with demeaning terms • Expecting certain items to always be in one's possession B. HARASSMENT HAZING : Behaviors that cause emotional anguish or physical discomfort in order to feel like part of the group. Harassment hazing confuses, frustrates, and causes undue stress for new members/rookies. (Some types of harassment hazing can also be considered violent hazing). -

Code of Virginia § 18.2-56. Hazing Unlawful; Civil and Criminal Liability; Duty of School, Etc., Officials; Penalty

Code of Virginia § 18.2-56. Hazing unlawful; civil and criminal liability; duty of school, etc., officials; penalty. 1. “It shall be unlawful to haze so as to cause bodily injury, any student at any school, college, or university. Any person found guilty thereof shall be guilty of a Class 1 misdemeanor. Any person receiving bodily injury by hazing shall have a right to sue, civilly, the person or persons guilty thereof, whether adults or infants. The president or other presiding official of any school, college or university receiving appropriations from the state treasury shall, upon satisfactory proof of the guilt of any student hazing another student, sanction and discipline such student in accordance with the institution's policies and procedures. The institution's policies and procedures shall provide for expulsions or other appropriate discipline based on the facts and circumstances of each case and shall be consistent with the model policies established by the Department of Education or the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, as applicable. The president or other presiding official of any school, college or university receiving appropriations from the state treasury shall report hazing which causes bodily injury to the attorney for the Commonwealth of the county or city in which such school, college or university is, who shall take such action as he deems appropriate. For the purposes of this section, ‘hazing’ means to recklessly or intentionally endanger the health or safety of a student or students or to inflict bodily injury on a student or students in connection with or for the purpose of initiation, admission into or affiliation with or as a condition for continued membership in a club, organization, association, Model Policy Regarding the Prevention of and Appropriate Disciplinary Action for Hazing at Virginia’s Institutions of Higher Education fraternity, sorority, or student body regardless of whether the student or students so endangered or injured participated voluntarily in the relevant activity.” 2. -

2019-20 New Student Handbook

2019-20 New Student Handbook Welcome to TU! First-year TU students, welcome Our goal as True Blue TU community members is foster to The University of Tulsa! We acceptance and inclusion and empower each student to are thrilled to have you on succeed. The TU faculty and staff are committed to our campus. Your first year at TU is campus, our community and our world. We can’t wait a time to explore the exciting to see a how your talent and determination improve opportunities available to new these spaces. students. Engagement is a huge part of your college experience, I invite you to find your own True Blue identity as a and I encourage you to find your fit among our diverse valued member of the TU family. I look forward to student body. seeing you around campus. Have a great year! Now is the time to engage in the university community Sincerely, to discover the true you. Participate in campus activities and make sure to care for yourself – both physically and mentally – and watch out for your friends, too. With new freedoms come new responsibilities, so make good Gerard P. Clancy, M.D. choices and support one another. President 1 Student handbook TU19155.indd 1 7/23/19 10:28 AM Founded in 1894, The University of Tulsa is a private, independent, support and psychological counseling. First-year students will be doctoral-degree-granting institution whose mission reflects these matched with student success coaches, and upperclassmen can core values: excellence in scholarship, dedication to free inquiry, enjoy mentoring and networking opportunities thanks to our integrity of character and commitment to humanity. -

Pranks, Hazing, and Bullying

Related Policies: Pranks, Hazing, and Bullying This policy is for internal use only and does not enlarge an employee’s civil liability in any way. The policy should not be construed as creating a duty to act or a higher duty of care with respect to third party civil claims against employees. A violation of this policy, if proven, can only form the basis of a complaint by this department for non- judicial administrative action in accordance with the laws governing employee discipline. Applicable State Statutes: OSHA: NFPA Standard: Date Implemented: Review Date: Policy: The fire department has a zero tolerance policy toward workplace and work related hazing or bullying. Hazing or bullying of members is unacceptable and will not be tolerated for any reason. All personnel should be able to work in an environment free of hazing and bullying. The department further does not tolerate work related pranks that violate a law or department rule, regulation or policy. Purpose: The purpose of this policy is to prohibit workplace and work related hazing and bullying. Workplace and work related hazing and bullying may cause the loss of trained and talented employees, reduce productivity and morale, and create unnecessary legal risks for the department. This policy also prohibits pranks that violate a law or department rule, regulation or policy. Definitions Bullying: Repetitive acts of aggressive behavior that intentionally threaten, humiliate, intimidate, degrade, or hurt, physically or mentally, another person. Bullying usually involves repeated acts committed by a person or group who has, or is perceived as having, more power than the victim/target of the bullying.