Emigration from Mexico and Central America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Volcanic Poetics: Revolutionary Myth and Affect in Managua and the Mission, 1961-2007 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/87h094jr Author Dochterman, Zen David Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Volcanic Poetics: Revolutionary Myth and Affect in Managua and the Mission, 1961-2007 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Zen David Dochterman 2016 © Copyright by Zen David Dochterman 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Volcanic Poetics: Revolutionary Myth and Affect in Managua and the Mission, 1961-2007 by Zen David Dochterman Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Efrain Kristal, Chair Volcanic Poetics: Revolutionary Myth and Affect in Managua and the Mission, 1961-2007 examines the development of Nicaraguan politically engaged poetry from the initial moments of the Sandinista resistance in the seventies to the contemporary post-Cold War era, as well as its impact on Bay Area Latino/a poetry in the seventies and eighties. This dissertation argues that a critical mass of politically committed Nicaraguan writers developed an approach to poetry to articulate their revolutionary hopes not in classical Marxist terms, but as a decisive rupture with the present order that might generate social, spiritual, and natural communion. I use the term “volcanic poetics” to refer to this approach to poetry, and my dissertation explores its vicissitudes in the political and artistic engagements of writers and poets who either sympathized with, or were protagonists of, the Sandinista revolution. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

Hispanic American Heritage Month September 15-October 15, 2017 Comp

Sonia Sotomayor Gloria Estefan Jennifer Lopez Ellen Ochoa U.S. Supreme Court Justice Renowned Singers NASA Astronaut Hispanic American Heritage Month September 15-October 15, 2017 Comp. & ed. by Mark Rothenberg Ponce de Leon J. Vasquez de Coronado Bernardo de Galves Juan Seguin Adm. David Farragut Discovered Florida American Southeast American Revolution Texas Independence New Orleans, Mobile Bay U.S. Civil War General Celebrating Hispanic and Latino Heritage, Culture, and Contributions in America (National Hispanic Heritage Month.com. Facebook.com) https://www.facebook.com/Nationalhispanicheritagemonth/?rc=p CNN Library. Hispanics in the U.S. Fast Facts (CNN, 3/31, 2017) http://www.cnn.com/2013/09/20/us/hispanics-in-the-u-s-/index.html Coreas, Elizabeth Mandy. “5 Things Hispanics Born in America Want You to Know.” (Huffington Post.com) http://www.huffingtonpost.com/elizabeth-mandy-coreas/5-things- hispanics-born-i_b_8397998.html Gamboa, Suzanne. “This Hispanic Heritage Month, What’s To Celebrate? We Asked.” (NBC News, September 17, 2017) https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/hispanic- heritage-month-what-s-there-celebrate-we-asked-n801776 Hispanic American Contributions to American Culture [video] (Studies Weekly. YouTube) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJt8FaPEPmI Hispanic Contributions (HispanicContributions.org) http://hispaniccontributions.org/ Hispanic Heritage Awards [9/14/17 at the Kennedy Center, Washington, DC] (Hispanic Heritage Foundation) http://hispanicheritage.org/programs/leadership/hispanic-heritage- awards/ Hispanic Heritage Month, September 15-October 15, 2017 = Mes de la Herencia Hispana (HispanicHeritageMonth.org) http://www.hispanicheritagemonth.org/ Hispanic Trends (Pew Research, 2017) http://www.pewhispanic.org/ Latino Americans (PBS Videos) http://www.pbs.org/latino-americans/en/watch- videos/#2365075996 ; http://www.pbs.org/latino-americans/es/watch- videos/#2365077219 Latino Cultures in the U.S.: Discover the Contributiuons and Experiences of Latinos in the U.S. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Political

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Political Incorporation of Children of Refugees: The Experience of Central Americans and Southeast Asians in the U.S. DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Political Science by Kenneth Chaiprasert Dissertation Committee: Professor Louis DeSipio, Chair Professor Carole Uhlaner Professor Linda Vo 2016 © 2016 Kenneth Chaiprasert DEDICATION To my parents and committee in recognition of their guidance and encouragement my most heartfelt gratitude and appreciation ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION x CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1 CHAPTER 2: Research Question, Theory, Methodology, 18 and Data Sources CHAPTER 3: Home-Country Politics and the Children 45 of Refugees CHAPTER 4: U.S. Politics and the Children of Refugees 84 CHAPTER 5: Politics and the Children of Refugees: 132 The Cambodian American Experience CHAPTER 6: Politics and the Children of Refugees: 204 The Salvadoran American Experience CHAPTER 7: Conclusion 259 BIBLIOGRAPHY/REFERENCES 278 APPENDIX 292 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 2.1 Relationship between Existing Scholarship and My theory 22 Figure 2.2 IIMMLA: Home-Country Politics Dependent Variables 24 Figure 2.3 IIMMLA: U.S. Politics Dependent Variables 24 Figure 2.4 IIMMLA: Independent Variable of Interest 25 Figure 2.5 IIMMLA: 1.5 or 2nd Generation Respondents, sorted by 25 Refugee Parentage Figure 2.6 LNS: Home-Country Politics Dependent Variables 27 Figure 2.7 LNS: U.S. Politics Dependent Variables 27 Figure 2.8 LNS: Independent Variable of Interest 28 Figure 2.9 LNS: 1.5 Generation Refugees 28 Figure 2.10 CILS: Home-Country Politics Dependent Variable 29 Figure 2.11 CILS: U.S. -

Nicaragua Collection (ASM0126)

University of Miami Special Collections Finding Aid - Nicaragua collection (ASM0126) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Special Collections 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-3247 Fax: (305) 284-4027 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/specialcollections/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/asm0126 Nicaragua collection Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Series descriptions ........................................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - ASM0126 Nicaragua collection Summary information Repository: University of Miami Special -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries 2016 Central and South America Rosalyn Wilsey, Lindsey Hershey, Alex Wilson and Kamila Aouchiche Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] Central and South America By: Lindsey Hershey, Kamila Aouchiche, Rosaline Wilsey, and Alex Wilson Florida State University SYD-2740 April 22, 2016 TIMELINE LINK: https://cdn.knightlab.com/libs/timeline3/latest/embed/index.html?source=1FxKy3Em_k02G8OF SKZucHC2N7Pc2dhuDbk2-foZxeHw&font=Default&lang=en&initial_zoom=2&height=650 Central Americans The rise of Central Americans living in the United States has grown dramatically in the last 50 years. In the 1970’s, demographics showed that “half of all Central American emigrants (those moving into other countries) relocated to other Central American countries, while half moved out of the region” (Woods, 2006). This immigration to other Central American Countries and the United States was caused by class division within Central American countries, such as Nicaragua. This ultimately led to revolutionaries, counterrevolutionaries, insurgencies, and civil warfare. Central Americans made up about 2.9 million of the total 9.7 million foreign-born population in the USA in 2009 (Terrazas, 2011,1). Changes in US laws in 1965 opened the doors to increased immigration, and larger waves of migration to the US began. These different policies came into place when natives of other countries chose to leave their country due to political turmoil, political persecution, natural disasters, and unlivable conditions. Immigration quotas from this policy allowed family reunification and political asylum in the United States. It offered a safe escape from immigrants’ home countries, which were often overwhelmed by political unrest and economic decline. -

'Unrooting' the American Dream: Exiling the Ethnospace in the Urban

782 WHERE DO YOU STAND ‘Unrooting’ the American Dream: Exiling the Ethnospace in the urban fractality of Miami ARMANDO MONTILLA Clemson University 1 ON ‘CITY FORM’ the new environment, the one encountered by arriv- ing migrants and the one being created by the trans- What causes the origins of City Form? Is there a formations occurring from such pattern of mobility. particular process, which occurs early since the be- ginning of their formation, when cities incorporate a 2 THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH: HISTORY OF certain ‘code of growth’, depicting specific character- MIAMI AS A CITY istics, which – similar to a what a particular genome does within biological ADN genetic sequences – re- Miami is – considered by statistical urban age stan- mains as part of the urban fabric growth patterns, dards – a young city, one of the fastest growing in throughout extended periods of time? Can certain the United States - considered one of the 20 cities populations affect this code, either following it or en- with most foreign immigration population compo- hancing it? Can a city be destined to grow unavoid- nent, in the world1 However its origins are anything ably following a certain pattern, then be impacted be but urban. When Ponce de León leaded the Spaniard specific modes of living, eventually creating a new expedition in 1531, which encountered the southern- type of hybrid, city form? most tip of the Florida Peninsula (then thought to be an island); he and his crew encountered a pristine, In the course of this paper I will try answering these natural yet hostile environment ‘city un-able’: Noth- questions, using the city of Miami in the United ing that would entice establishing a new settlement, States as a model for analysis in the field of con- among swam-like lowlands infested by mosquitoes, temporary urban growth, emphasizing on the multi- and other non- friendly-to-human species such as cultural qualities of its population, the modes of liv- alligators, besides other animal inhabitants of this ing these populations create, and how these modes otherwise natural paradise. -

Reconciling U.S. Property Claims in Cuba Transforming Trauma Into Opportunity

Reconciling U.S. Property Claims in Cuba Transforming Trauma into Opportunity Richard E. Feinberg DECEMBER 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements . iii 1 . Introduction and Overview . 1 2 . Nationalization and Compensation: U .S . and Cuban Positions . 6 3 . Claims of U .S . Nationals: Key Controversies . 16 4 . Frameworks for Reconciliation . 25 5 . Compensation Funds . 35 6 . A Grand Bargain? . 39 Annex: Top 50 Certified U.S. Corporate Claims . 42 About the Author . 44 Cover photos: “La Caballeria,” Raúl Corrales Forno . Secretary John Kerry shakes hands with Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez on the occasion of Kerry’s visit to Cuba for the reopening of the U .S . Embassy in Havana, U .S . Department of State . Both sourced from Wikimedia Commons, used under public domain . Reconciling U.S. Property Claims in Cuba: Transforming Trauma into Opportunity Latin America Initiative at Brookings i Brookings Publications on Cuba Since 2007, the Brookings Institution has produced a series of books, reports, policy briefs and articles on Cuba and its relations with the United States . Selected publications are listed below . For a complete list, see http://www .brookings .edu/research/topics/cuba Carlos Pascual and Vicki Huddleston, “Play a Part in Cuba’s Future,” Miami Herald, April 20, 2007 Cuba: A New Policy of Critical and Constructive Engagement, Foreign Policy at Brookings Report, April 2009 Vicki Huddleston and Carlos Pascual, Learning to Salsa: New Steps in U.S.-Cuba Relations (Washington, D .C .: Brookings Institution Press, 2010) Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado, Cuba’s Energy Future: Strategic Approaches to Cooperation (Washington, D .C .: Brookings Institution Press, 2010) Robert Muse and Jorge R . -

Toward an Understanding of Hispanic History

Portland Public Schools Geocultural Baseline Essay Series Hispanic-American Social-Science Baseline Essay 1996 Toward an Understanding of Hispanic History by Dr. Erasmo Gamboa John E. Bierwirth Superintendent Portland Public Schools 501 N. Dixon Street Portland, Oregon 97227 Copyright © 1996 by Multnomah School District 1J Portland, Oregon Version: 1996 PPS Geocultural Baseline EssaybSeries Erasmo Gamboa Social Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................1 Hispanic" Defined\.............................................................................................1 The Importance of Considering Nationality...................................................2 What Hispanics Think.......................................................................................3 THE RACIAL BACKGROUND AND CONQUEST.....................................................3 Native Peoples...................................................................................................3 The Spanish .......................................................................................................8 Conquest ............................................................................................................10 The African in Latin America ...........................................................................11 THE SPANISH COLONIAL SYSTEM..........................................................................12 Race Mixture—La Raza Cósmica -

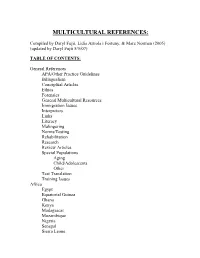

Multicultural References

MULTICULTURAL REFERENCES: Compiled by Daryl Fujii, Lidia Artiola i Fortuny, & Marc Norman (2005) (updated by Daryl Fujii 5/5/07) TABLE OF CONTENTS: General References APA/Other Practice Guidelines Bilingualism Conceptual Articles Ethics Forensics General Multicultural Resources Immigration Issues Interpreters Links Literacy Malingering Norms/Testing Rehabilitation Research Review Articles Special Populations Aging Child/Adolescents Other Test Translation Training Issues Africa Egypt Equatorial Guinea Ghana Kenya Madagascar Mozambique Nigeria Senegal Sierra Leone South Africa Sudan Tanzania Uganda Zaire Zambia Zimbabwe African Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Caribbean and Latin America Asian Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Bangla Deshi Chinese Filipino Guamanian-Chamorro Indian Indonesian Japanese Korean Laotian Malaysian Pakistani Singaporean Thai Vietnamese Americans of European Origin General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Austria Belgium Bosnia Bulgaria Croatia Czechoslovakia Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Great Britain Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy Latvia Lithuania Macedonia Malta Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Romania Russia Serbia Slovakia Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland Turkey Ukraine Australian/New Zealand Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transsexual Hispanic/Latino Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Argentina Brazil Chile Columbia Ecuador Mexico Peru Puerto Rico Venezuela Middle Eastern Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review -

The London School of Economics and Political Science ILL FARES the LAND: the LEGAL CONSEQUENCES of LAND CONFISCATIONS by THE

The London School of Economics and Political Science ILL FARES THE LAND: THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES OF LAND CONFISCATIONS BY THE SANDINISTA GOVERNMENT OF NICARAGUA 1979-1990 Benjamin B. Dille A thesis submitted to the Department of Law of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2012 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. The views expressed herein are my own alone and not those of the United States Department of State or the United States Government. 2 Abstract This thesis analyzes the consequences of property confiscations and redistribution under the Sandinista (FSLN) government in Nicaragua of the 1980s. It covers the period from the overthrow of Anastasio Somoza Debayle in 1979 to the February 1990 FSLN electoral defeat and the following two months of the Piñata, when the outgoing Sandinista government quickly formalized possession of property by new owners, both formerly landless peasants and the elite. -

Emigration from Mexico and Central America

The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies CCIS University of California, San Diego Moving Beyond the Policy of No Policy: Emigration from Mexico and Central America By Marc Rosenblum University of New Orleans Working Paper 54 June 2002 MOVING BEYOND THE POLICY OF NO POLICY: EMIGRATION FROM MEXICO AND CENTRAL AMERICA By Marc R. Rosenblum University of New Orleans [email protected] INCOMPLETE DRAFT: comments very welcome but not yet intended for general circulation! Abstract: Immediately following the 2000-1 inaugurations of Presidents Vicente Fox and George W. Bush, Mexico and the United States entered into intense negotiations aimed at a bilateral guestworker agreement on migration. Although the terror attacks of September, 2001 put these negotiations on hold, the progress which had been made—and the extent to which Mexico set the bilateral agenda—highlight the transnational character of U.S. immigration policy-making. But what do sending-states want when it comes to U.S. immigration policy, and when and how can they influence the process? This paper draws on 90 elite interviews conducted with Mexican, Central American, and Caribbean Basin policy-makers to answer these questions, and discusses Mexico’s increasing engagement in U.S. immigration policy-making since the 1980s. Rosenblum: Beyond the Policy of No Policy - 1 MOVING BEYOND THE POLICY OF NO POLICY: EMIGRATION FROM MEXICO AND CENTRAL AMERICA On September 5, 2001, Presidents Vicente Fox and George W. Bush met in Washington, DC, where the top item on the agenda was signing off on a final framework for negotiating a bilateral immigration accord. At first blush, the extraordinary bilateral priority placed on immigration—three cabinet-level semi-summits and three presidential summits in slightly over a year—is hard to explain in light of the Bush’s status as a conservative Republican, and widespread U.S.