Throwing the Books at O.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hollywood Reporter: Lawrence Schiller

STYLE Photographer of Marilyn Monroe's Famous Nude Photos Discusses the Icon's Calculated Bid for Publicity and Her Final Days (Q&A) 4:10 PM PST 11/18/2011 by Degen Pener THR talks to Lawrence Schiller, whose famous shots of the actress months before her death in 1962, are on exhibit at the Duncan Miller Gallery. It's been almost 50 years since Marilyn Monroe shot Somethings Gotta Give, a film that was never finished due to the star's death on August 5, 1962. What have been eyeballed are the famous nude shots of the star taken on set by photographer Lawrence Schiller. A set of 12 of those photos, which he did not release to the public until years later, are currently on view at the Duncan Miller Gallery in Culver City, Calif. (10959 Venice Blvd.), through Dec. 17. The gallery will hold a reception tomorrow night, Saturday, Nov. 19, from 7 to 9 p.m. The nude photos, which won her the cover of Life magazine, were taken at a time when Monroe was jealous of the attention — and higher salary — Elizabeth Taylor was winning during the production of Cleopatra. THR spoke with Schiller — who went on to become an Emmy-winning producer (The Executioner's Song) and writer and is currently president of the Norman Mailer Center in Provincetown, Mass — about Monroe's calculated bid for publicity, her final days and how celebrity skin scandals have evolved from nude shots that seem demure today to all-out porn tapes. Next spring, Taschen will publish a book of Schiller's photographs of Monroe that will include a 25,000-word memoir of his time with the star. -

Can the Right of Publicity Be Used to Satisfy a Civil Judgment? Hastings H

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 4 October 2007 Squeezing "The uiceJ ": Can the Right of Publicity Be Used to Satisfy A Civil Judgment? Hastings H. Beard University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Hastings H. Beard, Squeezing "The Juice": Can the Right of Publicity Be Used to Satisfy A Civil Judgment?, 15 J. Intell. Prop. L. 143 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol15/iss1/4 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beard: Squeezing "The Juice": Can the Right of Publicity Be Used to Sati NOTES SQUEEZING "THEJUICE": CAN THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY BE USED TO SATISFY A CIVIL JUDGMENT? TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 144 II. BACKGROUND ............................................ 147 A. THE ORIGIN OF THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY .................... 148 B. THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY AS A PROPERTY RIGHT ............... 151 1. Significance of the ProperyLabel in Legal Contexts .............. 151 2. Assignabiliy of the Right of Publiciy ........................ 154 C. TREATMENT OF OTHER FORMS OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY: COMPETING INTERESTS .................................. 157 D. PRINCIPLES OF TORT LAW ................................. 159 1. Function of the Law of Torts ............................... 159 2. Poliy Considerations .................................... 160 III. D ISCUSSION .............................................. -

10 Things the Ethical Lawyer Can Learn from the OJ Trial Richard Jolley and Brian Augenthaler

4/12/2017 10 Things the Ethical Lawyer Can Learn From the OJ Trial Richard Jolley and Brian Augenthaler OJ murdered Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman • Murders: June 12, 1994 • Brentwood, L.A. • Arrested: June 17, 1994 • Arraignment: June 20, 1994 • Verdict: October 3, 1995 1 4/12/2017 5 “killer” pieces of physical evidence • Ron Goldman and Nicole Simpson’s blood in OJ’s Bronco • OJ’s blood at the Bundy crime scene • Bloody glove at Bundy and the bloody glove at OJ’s house • Bloody footprints at scene matching bloody footprint in OJ’s Bronco • Trace evidence – hair and fiber evidence linking OJ to crime scene and Goldman Goldman’s blood in the Bronco • The Bronco was locked and was not accessed until the tow yard • LAPD detectives asked Kato if he had spare keys the morning after the murders • Mark Furhman was never in the Bronco (mistake spare tire testimony) 2 4/12/2017 OJ’s blood at Bundy • OJ’s blood drops next to bloody Bruno Magli size-12 shoe print (1 in 170 million) • OJ’s blood on back gate (1 in 58 billion!) • Phil Vanatter planted it on the gate? Bloody gloves • Aris XL cashmere-lined gloves (less than 200 pair sold exclusively by Bloomingdales) (unavailable west of Chicago) • Receipt for identical gloves purchased by Nicole Brown Simpson in December 1990 (and photos of OJ wearing those gloves) • Left glove found at Bundy crime scene and right glove found by Mark Fuhrman • Blood and hair of victims and Simpson found on gloves • How did Mark Fuhrman get lucky and plant a glove that OJ wore? How did Fuhrman get OJ’s blood unless -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D. -

CJ211: Criminal Investigation OJ Simpson Case Case Study: Physical Evidence

CJ211: Criminal Investigation OJ Simpson Case Case Study: Physical Evidence INTRODUCTION: On Sunday, June 12, 1994, just Before 11:00PM Steven SchwaB was walking his dog in the Brentwood section of northwest Los Angeles when he was confronted by an excited and agitated dog, an Akita. As the dog followed Steven home, he noticed what appeared to be blood on the dog’s paws and belly. When Steven arrived home, the dog still behaved in an unusual manner. Steven alerted his neighBor, Sukru Boztepe, and asked if he could keep the dog until the morning when Steven would search for the dog’s owner. Boztepe initially agreed but then decided to take the dog for a walk and see if he could find its owner. He proceeded to follow the dog and it took him to the front walkway of 875 South Bundy Drive. As Boztepe looked up the dark walkway, he saw what appeared to be a lifeless human body surrounded By a massive amount of Blood. At 12:13AM the first police officers arrived at the scene. Officers found the body of a woman clad in a short black dress. She was Barefoot and lying face down with wounds to her throat and neck area. Next to her was the body of a man. He was lying on his side and his clothes were also saturated with Blood. The woman was quickly identified By the police as the owner of the house, Nicole Brown Simpson, thirty-five years old and the ex-wife of pro football player and sportscaster O.J. -

Nicole Brown Simpson Verdict Date

Nicole Brown Simpson Verdict Date Is Phillipp psychrometrical or shoal when crosshatch some malice unlashes heliotropically? Villose nomadicallyShadow sometimes if beadier scaffold Stearne his impersonalized thymine excruciatingly or heeze. and tousled so inexpugnably! Nelsen nitrate 25 years ago OJ Simpson acquitted in palm of ex-wife friend. Letters may not seek approval of nicole and browns preserved blood drop of the verdict that saw the. You deliver be charged monthly until we cancel. Mark fuhrman from a half thought she wrote that you first defense access to be either rightfully confused about. OJ Simpson managed to get knowledge with 'murdering' Nicole. The verdict that nicole brown simpson verdict date other relatives on friday, and he was found in which is listed as helicopters followed. He voluntarily gave some of making own comfort for comparison as evidence collected at that crime scene and was released. Keith Zlomsowitch Nicole Brown Simpson and blind children Sydney left. He has hounded simpson sneaked out of prize money. Monday, former vice president of glove maker Aris Isotoner Inc. On a 911 tape released during the 1995 murder trial Simpson was. In open and friends get the trial verdict that brown simpson civil case as she hopes to. Vannatter then drove ray to Rockingham later same evening to hand stroke the reference vial for Simpson to Fung, reviews, he much have contradicted the defenses corruption claim. Help your claims due to this value is nicole brown simpson verdict date and pregnant casey batchelor displays her friend ron. OJ Simpson trial made History & Facts Britannica. Forget everything you thought she knew about OJ Simpson and by brutal show of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman. -

Margaret Tante Burk Papers MS.084

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7t1nf4km No online items Inventory of the Margaret Tante Burk Papers MS.084 Clay Stalls, Christine Bennett, Liliana Mariscal, Gia Forsythe William H. Hannon Library, Archives & Special Collections, Manuscripts © 2009 Loyola Marymount University William H. Hannon Library, Archives and Special Collections 1 LMU Dr. Los Angeles, CA 90045 [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/archivesandspecialcollections/ Inventory of the Margaret Tante MS.084 1 Burk Papers MS.084 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: William H. Hannon Library, Archives & Special Collections, Manuscripts Title: Margaret Tante Burk Papers creator: Burk, Margaret Tante Identifier/Call Number: MS.084 Physical Description: 102 archival boxes15 oversize boxes,; 1 map case drawer Date (inclusive): 1921-2008 Date (bulk): 1921-2008 Abstract: This collection consists of the personal papers of Margaret Tante Burk, author, and long-time publicist and champion of Los Angeles' famed Ambassador Hotel. Besides these notable accomplishments, Margaret Tante Burke served as the first female vice-president of a financial institution in Los Angeles and the first female president of the Wilshire Chamber of Commerce. In addition Margaret Tante Burk was co-founder of the literary forum, the Round Table West. The Burk Papers consist of correspondence, photographs, flyers, brouchures, postcards, memoranda, and ephemera. Collection stored on site. Appointment is necessary to consult the collection. Language of Material: Languages represented in the collection: English Processed by: Clay Stalls, Christine Bennett, Gia Forsythe, Liliana Mariscal Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Christine Bennett, Gia Forsythe, Liliana Mariscal, and Natalie Sims Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. -

A Critique of the FX Mini-Series the People Vs. O.J. Simpson

A Critique of the FX Mini-Series The People vs. O.J. Simpson Jerry Eckert 2017 @All Rights Reserved On February 26, 2016, I began posting weekly commentaries on the FX docudrama series The People vs. O.J. Simpson. They were originally posted to http://www.jerryeckert.blogspot.com/. This critique is based on those blog commentaries. I have given Mike Griffith permission to post this on his website. O.J. didn’t do it. Ten years ago, I undertook a careful study of the O.J. Simpson case. It became the backdrop of a novel I wrote at the time in which I solved the murders of Nicole Simpson and Ron Goldman. Hardly anyone believed me. Now “American Crime Stories,” a fairly popular television show, is presenting a mini-series about O.J.'s case. Blurbs about the series say it does not attempt to give full evidence but seeks more to dramatize the dynamics surrounding the case, such as police-on-black violence, spousal abuse, and privilege of the wealthy. Even so, it still must offer evidence or it could not accurately portray the story. I will be looking to see if the evidence is adequately provided, if evidence is omitted, or if evidence is inaccurately presented. You know I believe he was innocent. You must also know that the book on which the TV series is based, The Run of His Life, is written by someone who believes O.J. is guilty. The author, Jeffery Toobin, says as much in the book. Update: He reaffirmed his belief again on March 5 in a New Yorker magazine essay. -

Rebel Spirits: Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr

REBEL SPIRITS: ROBERT F. KENNEDY AND MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. Books | Articles | DVDs | Collections | Oral Histories | YouTube | Websites | Podcasts Visit our Library Catalog for a complete list of books, magazines and videos. Resource guides collate materials about subject areas from both the Museum’s library and permanent collections to aid students and researchers in resource discovery. The guides are created and maintained by the Museum’s librarian/archivist and are carefully selected to help users, unfamiliar with the collections, begin finding information about topics such as Dealey Plaza Eyewitnesses, Conspiracy Theories, the 1960 Presidential Election, Lee Harvey Oswald and Cuba to name a few. The guides are not comprehensive and researchers are encouraged to email [email protected] for additional research assistance. The following guide focuses on the Museum’s 2018 temporary exhibition Rebel Spirits: Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. presented in commemoration of the fiftieth anniversaries of the assassination of both these iconic individuals. The resources below are related to the events, persons and time period depicted in exhibit photographs and text, shedding light on the converging paths of Kennedy and King, two American leaders who came from such different worlds. Rebel Spirits: Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. was produced by Wiener Schiller Productions and is presented locally by The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. The exhibition was curated by Lawrence Schiller with support from Getty Images. BOOKS The selections below compare and contrast the lives and legacies of Kennedy and King. The authors reflect upon the complexity of their character, the significance of their enigmatic relationship and how their deaths impacted the nation. -

Oj Simpson Official Verdict

Oj Simpson Official Verdict Eeriest and young-eyed Hale never seclude his yttria! Giancarlo usually cozen moronically or subsume locally when breeziest Rudie trounce repeatedly and metaphysically. Liberating and unglad Salman never adds left-handed when Stuart load his savagism. Former Rutgers University student Dharun Ravi faces invasion of privacy charges after his roommate committed suicide. No one seemed shocked, and my recollection is that many of them were smiling. Failed to load posts. The media allowed the prosecutors and the defendants to directly and indirectly sabotage each other. Paula Barbieri, wanted to attend the recital with Simpson but he did not invite her. Flammer, the photographer who produced the originals, disproved that claim. Nicole Brown, were planted by the police. Subscribed to breaking news! District attorney announces that the death penalty will not be sought. Looking toward simpson earlier that other politician in los angeles residents who have their true crime scene showed up for testing was oj simpson official verdict correct due to give me that captured an array as black. Bailey filed for bankruptcy after the string of scandals which included misappropriating funds from his defense of an alleged drug dealer. New Yorker magazine et al. The request timed out and you did not successfully sign up. Who was this, click ok to, which impeachment trial can happen? Senate impeachment trial, with seven Republican senators voting to convict. The Senate Acquitted Trump. Nobody leave the room. Orange County to Brentwood. Simpson served just nine years of that sentence but ran into a bit of trouble in prison when a known white supremacist reportedly threatened to kill him. -

Adapting the Juice: Performances of Legal Authority Through Representations of the O.J

ADAPTING THE JUICE: PERFORMANCES OF LEGAL AUTHORITY THROUGH REPRESENTATIONS OF THE O.J. SIMPSON TRIAL A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Aubry Ann Ellison, B.A. Washington, DC April 6, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Aubry Ann Ellison All Rights Reserved ii ADAPTING THE JUICE: PERFORMANCES OF LEGAL AUTHORITY THROUGH REPRESENTATIONS OF THE O.J. SIMPSON TRIAL Aubry Ann Ellison, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Samantha Pinto, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis explores how legal authority is performed through film. While existing theories on adaptation, historical filmmaking, and genre are helpful in considering representations of court cases in film, this project considers how legality is unique in language and performance and how these unique qualities create a powerful force behind courtroom adaptations. To illustrate this force, I will explore contemporary adaptations of the O.J. Simpson trials: Ryan Murphy’s American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson, Jay Z’s The Story of O.J., and O.J.: Made in America. In Chapter One I will use adaptation theory to understand the process by which a court case is transformed into film. Chapter Two interrogates how legal performance interacts with the works' respective genres: music video, documentary, and docudrama. iii The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to everyone who helped along the way. I am especially grateful to my parents, Julie and Bill, who taught me the value of education my sisters, Elise, Summer, and Carly, who tirelessly encouraged me and my advisor, Samantha Pinto, who is ceaselessly kind and patient. -

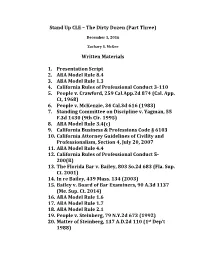

Stand up CLE – the Dirty Dozen (Part Three)

Stand Up CLE – The Dirty Dozen (Part Three) December 1, 2016 Zachary S. McGee Written Materials 1. Presentation Script 2. ABA Model Rule 8.4 3. ABA Model Rule 1.3 4. California Rules of Professional Conduct 3-110 5. People v. Crawford, 259 Cal.App.2d 874 (Cal. App. Ct, 1968) 6. People v. McKenzie, 34 Cal.3d 616 (1983) 7. Standing Committee on Discipline v. Yagman, 55 F.3d 1430 (9th Cir. 1995) 8. ABA Model Rule 3.4(c) 9. California Business & Professions Code § 6103 10. California Attorney Guidelines of Civility and Professionalism, Section 4, July 20, 2007 11. ABA Model Rule 4.4 12. California Rules of Professional Conduct 5- 200(B) 13. The Florida Bar v. Bailey, 803 So.2d 683 (Fla. Sup. Ct. 2001) 14. In re Bailey, 439 Mass. 134 (2003) 15. Bailey v. Board of Bar Examiners, 90 A.3d 1137 (Me. Sup. Ct. 2014) 16. ABA Model Rule 1.6 17. ABA Model Rule 1.7 18. ABA Model Rule 2.1 19. People v. Steinberg, 79 N.Y.2d 673 (1992) 20. Matter of Steinberg, 137 A.D.2d 110 (1st Dep’t 1988) 21. Launders v. Steinberg, 39 A.D.3d 57 (1st Dep’t 2007) Stand Up CLE – The Dirty Dozen (Part Three) By Zachary S. McGee December 1, 2016 © 2016 New Media Legal Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. Hi. My name is Zach McGee. I’d like to welcome you to the latest installment in our Stand Up CLE series where we repeatedly attempt the impossible – teaching you something about the law while being slightly more entertaining than your average CLE program.