19.05.09 Front Matter Mine 2.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geophysical Mapping of Mount Bonnell Fault of Balcones Fault Zone

Geophysical mapping of Mount Bonnell fault of Balcones fault zone and its implications on Trinity-Edwards Aquifer interconnection, central Texas, USA Mustafa Saribudak1 Abstract There are up to 1200 ft (365 m) of total displacement across the Geophysical surveys (resistivity, natural potential [self-po- BFZ. Faults generally dip steeply (45–85°), varying primarily tential], conductivity, magnetic, and ground penetrating radar) due to specific rock properties and local stress fields (Ferrill and were conducted at three locations across the Mount Bonnell fault Morris, 2008). in the Balcones fault zone of central Texas. The normal fault has The BFZ includes the Edwards and Trinity aquifers, which hundreds of meters of throw and is the primary boundary between are primary sources of water for south-central Texas communities, two major aquifers in Texas, the Trinity and Edwards aquifers. including the city of San Antonio. The Trinity Aquifer underlies In the near surface, the fault juxtaposes the Upper Glen Rose the Edwards Aquifer through the Balcones fault zone. Formation on the Edwards Plateau, consisting of interbedded The BFZ’s most prominent fault is the Mount Bonnell, with limestone and marly limestone, against the Edwards Group, which a vertical throw of up to 600 ft (183 m) (Figure 1). The fault is mostly limestone, on the eastern down-thrown side (coastal hydrogeologically juxtaposes these Cretaceous carbonate aquifers plain). The Upper Glen Rose member is considered to be the during the Miocene tectonic deformation associated with the Upper Trinity Aquifer and also a confining zone underlying the Balcones fault zone, where the younger Edwards Group limestone Edwards Aquifer. -

Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS

STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS Report to the Governor October 2009 Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR OCTOBER 2009 TEXAS GENERAL LAND OFFICE JERRY PATTERSON, COMMISSIONER INTRODUCTION SB 1262 Summary Texas Natural Resources Code, Chapter 31, Subchapter E, [Senate Bill 1262, 74th Texas Legislature, 1995] amended two years of previous law related to the reporting and disposition of state agency land. The amendments established a more streamlined process for disposing of unused or underused agency land by defining a reporting and review sequence between the Land Commissioner and the Governor. Under this process, the Asset Management Division of the General Land Office provides the Governor with a list of state agency properties that have been identified as unused or underused and a set of recommended real estate transactions. The Governor has 90 days to approve or disapprove the recommendations, after which time the Land Commissioner is authorized to conduct the approved transactions. The statute freezes the ability of land-owning state agencies to change the use or dispose of properties that have recommended transactions, from the time the list is provided to the Governor to a date two years after the recommendation is approved by the Governor. Agencies have the opportunity to submit to the Governor development plans for the future use of the property within 60 days of the listing date, for the purpose of providing information on which to base a decision regarding the recommendations. The General Land Office may deduct expenses from transaction proceeds. -

No. 21-0170 in the SUPREME COURT of TEXAS RESPONSE BY

FILED 21-0170 3/2/2021 10:56 AM tex-51063305 SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS BLAKE A. HAWTHORNE, CLERK No. 21-0170 _______________________________________ IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS _______________________________________ IN RE LINDA DURNIN, ERIC KROHN, AND MICHAEL LOVINS, Relators. _______________________________________ ORIGINAL PROCEEDING ______________________________________ RESPONSE BY CITY OF AUSTIN AND AUSTIN CITY COUNCIL IN OPPOSITION TO FIRST AMENDED ORIGINAL EMERGENCY PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS _______________________________________ Anne L. Morgan, City Attorney Renea Hicks State Bar No. 14432400 LAW OFFICE OF Meghan L. Riley, Chief-Litigation RENEA HICKS State Bar No. 24049373 State Bar No. 09580400 CITY OF AUSTIN–LAW DEP’T. P.O. Box 303187 P.O. Box 1546 Austin, Texas 78703-0504 Austin, Texas 78767-1546 (512) 480-8231 (512) 974-2268 [email protected] ATTORNEYS FOR RESPONDENTS CITY OF AUSTIN AND AUSTIN CITY COUNCIL IDENTITY OF PARTIES AND COUNSEL Party’s name Party’s status Attorneys for parties LINDA DURNIN Relators Donna García Davidson ERIC KROHN Capitol Station, P.O. Box 12131 MICHAEL LOVINS Austin, Texas 78711 Bill Aleshire ALESHIRELAW, P.C. 3605 Shady Valley Dr. Austin, Texas 78739 CITY OF AUSTIN Respondents Renea Hicks AUSTIN CITY LAW OFFICE OF RENEA HICKS COUNCIL P.O. Box 303187 Austin, Texas 78703-0504 Anne L. Morgan, City Attorney Meghan L. Riley, Chief – Litiga- tion CITY OF AUSTIN–LAW DEP’T. P. O. Box 1546 Austin, Texas 78767-1546 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Identity of Parties and Counsel ........................................................ -

South Congress Prostitution Problem Is Said to Be About 150 Years Old

99-03 So. Congress Prostitution Problem April 1999 ABSTRACT C>outh Austin's century and half year old history of prostitution which was on the Grand Avenue leading to the Capitol of the State of Texas, was responsible for disrupting the lives of business people and the citizens who live there. In 1992 citizens began meeting with the police to express their concerns over the growing problem of prostitution, especially the presence of a hill top pornographic theater across from a junior high school. Using police stings, they often netted over a hundred "Johns" along with an elected state official. It 1995 a new way of addressing the problem was formally put into action. A.P.D. Crime Net South officers began to address the issues of prostitution by using the SARA model. Now a former feed store and hot bed for prostitution, has become a Mexican Restaurant where President Bill Clinton ate. SCANNING: The Crime Net unit looked at the long history of prostitution, they surveyed police reports, talked to fellow officers and with citizens. They found that a high number of police calls for service were taking place at several motels along South Congress. They used surveillance, undercover buys, stepped up patrols and the abatement law to gather additional information ANALYSIS: In assessing the problem they found that the motels in question seemed to encourage and support the presences of the prostitute by allowing them on the property along with drug dealers. Sometimes the motel employees were the drug dealers. RESPONSE: They meet with the owners and neighborhood associations to talk about the problems. -

2017 Central Texas Runners Guide: Information About Races and Running Clubs in Central Texas Running Clubs Running Clubs Are a Great Way to Stay Motivated to Run

APRIL-JUNE EDITION 2017 Central Texas Runners Guide: Information About Races and Running Clubs in Central Texas Running Clubs Running clubs are a great way to stay motivated to run. Maybe you desire the kind of accountability and camaraderie that can only be found in a group setting, or you are looking for guidance on taking your running to the next level. Maybe you are new to Austin or the running scene in general and just don’t know where to start. Whatever your running goals may be, joining a local running club will help you get there faster and you’re sure to meet some new friends along the way. Visit the club’s website for membership, meeting and event details. Please note: some links may be case sensitive. Austin Beer Run Club Leander Spartans Youth Club Tejas Trails austinbeerrun.club leanderspartans.net tejastrails.com Austin FIT New Braunfels Running Club Texas Iron/Multisport Training austinfit.com uruntexas.com texasiron.net New Braunfels: (830) 626-8786 (512) 731-4766 Austin Front Runners http://goo.gl/vdT3q1 No Excuses Running Texas Thunder Youth Club noexcusesrunning.com texasthundertrackclub.com Austin Runners Club Leander/Cedar Park: (512) 970-6793 austinrunners.org Rogue Running roguerunning.com Trailhead Running Brunch Running Austin: (512) 373-8704 trailheadrunning.com brunchrunning.com/austin Cedar Park: (512) 777-4467 (512) 585-5034 Core Running Company Round Rock Stars Track Club Tri Zones Training corerunningcompany.com Youth track and field program trizones.com San Marcos: (512) 353-2673 goo.gl/dzxRQR Tough Cookies -

Austin Police Department Patrol Utilization Study

AUSTIN POLICE DEPARTMENT PATROL UTILIZATION STUDY FINAL REPORT July 2012 1120 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 930 Washington, DC 20036 Executive Summary Sworn Staffing for the Austin Police Department The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) was retained by the City of Austin to provide the Austin City Council and City Executives with recommendations for an innovative, sustainable method to determine current and future police department staffing needs. The objectives of the study include: reviewing the current demand for sworn law enforcement, including calls for service, investigative workload, staffing for special events, and utilization of support staff; examining benchmarks for police staffing that are used in a sample of U.S. cities with populations from 500,000 to one million; gathering information on local community expectations regarding perceptions of safety, crime reduction strategies, community policing, and patrol utilization; recommending a methodology for the calculation of police staffing needs that can be updated and replicated by city staff in the future; and providing recommendations regarding three- to five-year staffing projections based on the community-based goals. Assessing Police Staffing Officers per Thousand Population One measure that has been used for some time to assess officer staffing levels in Austin has been a ratio of officers per thousand residents. For a number of years the City has used “two per thousand” as its benchmark for minimum police staffing. The city’s population in April 2012 was listed as 824,205 which would dictate that the sworn staffing of the Austin Police Department (APD) be authorized at a minimum of 1,648. Although the two-per-thousand ratio is convenient and provides dependable increases in police staffing as the city’s population rises, it does not appear to be based on an objective assessment of policing needs in Austin. -

Office of the District Attorney P.O

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY P.O. Box 1748, Austin, TX 78767 JOSÉ P. GARZA Telephone 512/854-9400 TRUDY STRASSBURGER DISTRICT ATTORNEY Telefax 512/854-4206 FIRST ASSISTANT For Immediate Release: January 14, 2021 Media Contact: Alexa Etheredge at [email protected] or (512) 364-4185 Travis County District Attorney Releases Information on Cases of Potential Law Enforcement Misconduct Two 2021 Officer-Involved Shooting Cases to Be Presented to Grand Jury Ramos and Ambler Cases to Be Presented Before the Expiration of the Current Grand Jury Term in March AUSTIN, TX -- Today, Travis County District Attorney José Garza released detailed information on the status of every case pending in the Office’s Civil Rights Unit. The information released includes the date of the incident; a summary of the facts known to the office; the status of the case within the office; and when possible, the name of the complainant or decedent, the name of the officer or officers, and a timeline for presenting the case to the grand jury. Additionally, District Attorney Garza released details about two officer-involved shootings that took place in the first week of 2021. He disclosed that his Office’s prosecutors responded to the scene within hours of the incident occurring and are actively investigating the incidents. In keeping with policy, the Office will present both cases to the grand jury. “Already this year, there have been two officer-involved shootings. In total, two people were injured, and Alexander Gonzales was killed. It is a tragedy for our community, and I would like to express my sympathies to the family of Mr. -

Cause No. ___GRAYSON COX, SABRINA BRADLEY, § in THE

4/26/2016 2:18:17 PM Velva L. Price District Clerk Travis County Cause No. D-1-GN-16-001762____________ D-1-GN-16-001762 Victoria Chambers GRAYSON COX, SABRINA BRADLEY, § IN THE DISTRICT COURT DANIEL DE LA GARZA, PIMPORN MAYO, § JEFFREY MAYO, RYDER JEANES, § JOSEPHINE MACALUSO, AMITY § COURTOIS, PHILIP COURTOIS, ANDREW § BRADFORD, MATTHEW PERRY, § TIMOTHY HAHN, GARY CULPEPPER, § CHERIE HAVARD, ANDREW COULSON, § LANITH DERRYBERRY, LINDA § 126th _____ JUDICIAL DISTRICT DERRYBERRY, ROSEANNE GIORDANI, § BETTY LITTRELL, and BENNETT BRIER, § § Plaintiffs, § v. § § CITY OF AUSTIN, § § Defendant. § TRAVIS COUNTY, TEXAS PLAINTIFFS’ ORIGINAL PETITION FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT Plaintiffs Grayson Cox, et al, file this petition for declaratory judgment, complaining of the City of Austin and seeking a declaratory judgment determining and confirming certain important rights guaranteed to them by state statute to protect the use and enjoyment of their property and homes. A. SUMMARY OF THE CASE AND REQUESTED RELIEF 1. This case involves the interpretation of the Valid Petition Rights section of the Texas Zoning Enabling Act, Texas Local Government Code Section 211.006(d) (the “Valid Petition Rights Statute”). That statute requires a ¾ vote of a City Council to approve any change in zoning regulations that are protested by at least 20% of the landowners in the area. 1 The requisite 20% of the neighboring landowners have submitted valid petitions objecting to the approval of the proposed zoning regulation changes for the Grove at Shoal Creek Planned Unit Development (herein “Grove PUD”). That Grove PUD is proposed as a high-density mixed-use development on a 76 acre tract of land at 4205 Bull Creek Road in Austin, Texas, commonly called the “Bull Creek Tract.” 2. -

4323 Mount Bonnell RD, Austin TX 78731

$9,995,000.00, 4323 Mount Bonnell RD, Austin TX 78731 MLS® 7650067 Rare development opportunity on this premier west Austin property that is beautifully positioned on a hill above Lake Austin and prestigious Mount Bonnell Road. The one-of-a-kind estate property offers ultimate privacy along with unparalleled views of Lake Austin, the Pennybacker Bridge, and the Hill Country. Brightleaf Nature Preserve surrounds the property and creates a natural sanctuary of beauty and tranquility. This 5.93- acre tract is conveniently located minutes from downtown Austin, nationally renowned restaurants, intimate music venues, boutique shopping, Lady Bird Lake, and the hike and bike trail. The central location provides ease and convenience to city living but allows a retreat to seclusion and privacy. This estate site provides an opportunity for your imagination to soar with the possibilities of creating the ultimate retreat. Imagine a private winding drive leading up the hillside where you are immediately captivated by the wrestling of trees and nature. As you approach the top of the hill you are greeted with unmatched lake views, beauty and tranquility. The building site allows vision to design, build, and curate an architectural gem nestled on the hillside above Lake Austin. This is a rare opportunity to own and build a fabulous estate property in central Austin. Listing Details MLS® # 7650067 Price 9,995,000.00 Status Active Type Land Sub-Type Single Lot Neighborhood Mount Bonnell Year Built Square Feet Lot Size 258310.8 Bedrooms 0 Bathrooms This information was printed from fuserealty.com on 10/02/2021. Use For more information about this or similar properties, contact Us The information being provided is for consumers' personal, non-commercial use and may not be used for any purpose other than to identify prospective properties consumers may be interested in purchasing. -

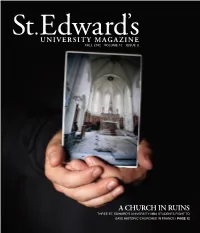

St. Edward's University Magazine Fall 2012 Issue

’’ StSt..EdwardEdwardUNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY MAGAZINEMAGAZINEss SUMMERFALL 20201121 VOLUME 112 ISSUEISSUE 23 A CHurcH IN RUINS THree ST. EDWarD’S UNIVERSITY MBA STUDENts FIGHT TO save HISTORIC CHurCHes IN FraNCE | PAGE 12 79951 St Eds.indd 1 9/13/12 12:02 PM 12 FOR WHOM 18 MESSAGE IN 20 SEE HOW THEY RUN THE BELLS TOLL A BOTTLE Fueled by individual hopes and dreams Some 1,700 historic French churches Four MBA students are helping a fourth- plus a sense of service, four alumni are in danger of being torn down. Three generation French winemaker bring her share why they set out on the rocky MBA students have joined the fight to family’s label to Texas. road of campaigning for political office. save them. L etter FROM THE EDitor The Catholic church I attend has been under construction for most of the The questions this debate stirs are many, and the passion it ignites summer. There’s going to be new tile, new pews, an elevator, a few new is fierce. And in the middle of it all are three St. Edward’s University MBA stained-glass windows and a bunch of other stuff that all costs a lot of students who spent a good part of the summer working on a business plan to money. This church is 30 years old, and it’s the third or fourth church the save these churches, among others. As they developed their plan, they had parish has had in its 200-year history. to think about all the people who would be impacted and take into account Contrast my present church with the Cathedral of the Assumption in culture, history, politics, emotions and the proverbial “right thing to do.” the tiny German village of Wolframs-Eschenbach. -

Assistant Director, Austin Water Employee Leadership & Development

Assistant Director, Austin Water Employee Leadership & Development CITY OF AUSTIN, TEXAS UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY The City of Austin is seeking a highly qualified individual to fill the Employee Leadership & Development Assistant Director position which reports to the Austin Water Director. AUSTIN, TEXAS This vibrant and dynamic city tops numerous lists for business, entertainment, and quality of life. One of the country’s most popular, high-profile “green” and culturally dynamic cities, Austin was selected as the “Best City for the Next Decade” (Kiplinger, 2010), the “Top Creative Center” in the US (Entrepreneur.com, 2010), #1 on the Best Place to Live in the U.S. and #4 on the Best Places to Retire (U.S. News & World Report, 2019) , and ranked in the top ten on Forbes list of America’s Best Employers for 2017. Austin’s vision is to be a beacon of sustainability, social equity, and economic opportunity; where diversity and creativity are celebrated; where community needs and values are recognized; where leadership comes from its community members, and where the necessities of life are affordable and accessible to all. Austin is a player on the international scene with such events as SXSW, Austin City Limits, Urban Music Fest, Austin Film Festival, Formula 1 and home to companies such as Apple, Samsung, Dell and Ascension Seton Health. From the home of state government and the University of Texas, to the Live Music Capital of the World and its growth as a film center, Austin has gained worldwide attention as a hub for education, business, health, and sustainability. The City offers a wide range of events, from music concerts, food festivals, and sports competitions to museum displays, exhibits, and family fun. -

Groundwater Availability of the Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer, Texas: Numerical Simulations Through 2050

GROUNDWATER AVAILABILITY OF THE BARTON SPRINGS SEGMENT OF THE EDWARDS AQUIFER, TEXAS: NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS THROUGH 2050 by Bridget R. Scanlon, Robert E. Mace*, Brian Smith**, Susan Hovorka, Alan R. Dutton, and Robert Reedy prepared for Lower Colorado River Authority under contract number UTA99-0 Bureau of Economic Geology Scott W. Tinker, Director The University of Texas at Austin *Texas Water Development Board, Austin **Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, Austin October 2001 GROUNDWATER AVAILABILITY OF THE BARTON SPRINGS SEGMENT OF THE EDWARDS AQUIFER, TEXAS: NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS THROUGH 2050 by Bridget R. Scanlon, Robert E. Mace*1, Brian Smith**, Susan Hovorka, Alan R. Dutton, and Robert Reedy prepared for Lower Colorado River Authority under contract number UTA99-0 Bureau of Economic Geology Scott W. Tinker, Director The University of Texas at Austin *Texas Water Development Board, Austin **Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, Austin October 2001 1 This study was initiated while Dr. Mace was an employee at the Bureau of Economic Geology and his involvement primarily included initial model development and calibration. CONTENTS ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................1 STUDY AREA...................................................................................................................................3