THE HUSBANDRY and BREEDING of the ROSY BOA LICHA- By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rubber Boas in Radium Hot Springs: Habitat, Inventory, and Management Strategies

Rubber Boas in Radium Hot Springs: Habitat, Inventory, and Management Strategies ROBERT C. ST. CLAIR1 AND ALAN DIBB2 19809 92 Avenue, Edmonton, AB, T6E 2V4, Canada, email [email protected] 2Parks Canada, Box 220, Radium Hot Springs, BC, V0A 1M0, Canada Abstract: Radium Hot Springs in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia is home to a population of rubber boas (Charina bottae). This population is of ecological and physiological interest because the hot springs seem to be a thermal resource for the boas, which are near the northern limit of their range. This population also presents a dilemma to park management because the site is a major tourist destination and provides habitat for the rubber boa, which is listed as a species of Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). An additional dilemma is that restoration projects, such as prescribed logging and burning, may increase available habitat for the species but kill individual snakes. Successful management of the population depends on monitoring the population, assessing the impacts of restoration strategies, and mapping both summer and winter habitat. Hibernation sites may be discovered only by using radiotelemetry to follow individuals. Key Words: rubber boa, Charina bottae, Radium Hot Springs, hot springs, snakes, habitat, restoration, Kootenay National Park, British Columbia Introduction The presence of rubber boas (Charina bottae) at Radium Hot Springs in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia (B.C.) presents some unusual challenges for wildlife managers because the site is a popular tourist resort and provides habitat for the species, which is listed as a species of Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC 2004). -

Review of Species Selected at SRG 45 Following Working Group Recommendations on Reptiles and One Scorpion from Benin, Ghana and Togo

Review of species selected at SRG 45 following working group recommendations on reptiles and one scorpion from Benin, Ghana and Togo (Version edited for public release) A report to the European Commission Directorate General E - Environment ENV.E.2. – Environmental Agreements and Trade by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre November, 2008 UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road Cambridge CB3 0DL CITATION United Kingdom UNEP-WCMC (2008). Review of species selected at SRG 45 following working group recommendations on reptiles Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314 and one scorpion from Benin, Ghana and Togo. A Report Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136 to the European Commission. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge. Email: [email protected] Website: www.unep-wcmc.org PREPARED FOR ABOUT UNEP-WORLD CONSERVATION The European Commission, Brussels, Belgium MONITORING CENTRE The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre DISCLAIMER (UNEP-WCMC), based in Cambridge, UK, is the The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect specialist biodiversity information and assessment the views or policies of UNEP or contributory centre of the United Nations Environment organisations. The designations employed and the Programme (UNEP), run cooperatively with WCMC presentations do not imply the expressions of any 2000, a UK charity. The Centre's mission is to opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP, the evaluate and highlight the many values of European Commission or contributory organisations biodiversity and put authoritative biodiversity concerning the legal status of any country, territory, knowledge at the centre of decision-making. city or area or its authority, or concerning the Through the analysis and synthesis of global delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Northern Rubber Boa (Charina Bottae) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling

Northern Rubber Boa (Charina bottae) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling Distribution Status: Resident Year Round State Rank: S4 Global Rank: G5 Modeling Overview Created by: Bryce Maxell & Braden Burkholder Creation Date: October 1, 2017 Evaluator: Bryce Maxell Evaluation Date: October 1, 2017 Inductive Model Goal: To predict the distribution and relative suitability of general year-round habitat at large spatial scales across the species’ known range in Montana. Inductive Model Performance: The model does a good job of reflecting the distribution of Northern Rubber Boa general year-round habitat suitability at larger spatial scales across the species’ known range in Montana. Evaluation metrics indicate a good model fit and the delineation of habitat suitability classes is well-supported by the data. Deductive Model Goal: To represent the ecological systems commonly and occasionally associated with this species year-round, across the species’ known range in Montana. Deductive Model Performance: Ecological systems that this species is commonly and occasionally associated with over represent the amount of suitable habitat for Northern Rubber Boa across the species’ known range in Montana and this output should be used in conjunction with inductive model output for survey and management decisions. Suggested Citation: Montana Natural Heritage Program. 2017. Northern Rubber Boa (Charina bottae) predicted suitable habitat models created on October 01, 2017. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 15 pp. Montana Field Guide Species Account: http://fieldguide.mt.gov/speciesDetail.aspx?elcode=ARADA01010 page 1 of 15 Northern Rubber Boa (Charina bottae) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling October 01, 2017 Inductive Modeling Model Limitations and Suggested Uses This model is based on statewide biotic and abiotic layers originally mapped at a variety of spatial scales and standardized to 90×90 meter raster pixels. -

Nevada Department of Wildlife

STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Wildlife Diversity Division 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Ste 120 • Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 688-1500 Fax (775) 688-1697 #18 B MEMORANDUM August 30, 2018 To: Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners, County Advisory Boards to Manage Wildlife, and Interested Publics From: Jennifer Newmark, Administrator, Wildlife Diversity Division Title: Commission General Regulation 479, Rosy Boa Reptile, LCB File No. R152- 18 – Wildlife Diversity Administrator Jennifer Newmark and Wildlife Diversity Biologist Jason Jones – For Possible Action Description: The Commission will consider adopting a regulation relating to amending Chapter 503 of the Nevada Administrative Code (NAC). This amendment would revise the scientific name of the rosy boa, which is classified as a protected reptile, from Lichanura trivirgata to Lichanura orcutti. This name change is needed due to new scientific studies that have split the species into two distinct entities, one that occurs in Nevada and one that occurs outside the state. Current NAC protects the species outside Nevada rather than the species that occurs within Nevada. The Commission held a workshop on Aug. 10, 2018, and the Commission directed the Department to move forward with an adoption hearing. Summary: A genetics study in 2008 by Woods et al. split the rosy boa into two distinct species – the three- lined boa (Lichanura trivirgata) and the rosy boa (Lichanura orcutti). This split was formally recognized in 2017 by the Committee on Standard English and Scientific Names by the Society of the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Three-lined boas, Lichanura trivirgata, occur in Baja California, Southern Arizona and Sonora Mexico, while the rosy boa, Lichanura orcutti occur in Nevada, parts of California and northern Arizona. -

Calabaria and the Phytogeny of Erycine Snakes

<nological Journal of the Linnean Socieb (1993), 107: 293-351. With 19 figures Calabaria and the phylogeny of erycine snakes ARNOLD G. KLUGE Museum of <oolog~ and Department of Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mr 48109 U.S.A. Receiued October 1991, revised manuscript accepted Mar I992 Two major subgroups of erycine snakes, designated Charina and Eyx, are delimited with a cladistic analysis of 75 morphological characters. The hypotheses of species relationships within the two clades are (reinhardtii (bottae, triuirgata) ) and (colubrinus, conicus, elegans, jayakari, muellen’, somalicus (miliaris (tataricus (iaculus, johnii)))),respectively. This pattern of grouping obtains without assuming multistate character additivity. At least 16 synapomorphies indicate that reinhardtii is an erycine and that it is the sister lineage of the (bottae, friuirgata) cladr. Calabaria and Lichanura are synonymized with Charina for reasons of taxonomic efficiency, and to emphasize the New-Old World geographic distribution of the three species in that assemblage. Further resolution of E’yx species relationships is required before Congylophis (type species conicus) can be recognized. ADDITIONAL KEY WORDS:--Biogeography - Cladistics - erycines - fossils - taxonomy CONI‘EN’I’S Introduction ................... 293 Erycine terminal taxa and nomenclature ............ 296 Fossils .................... 301 Methods and materials ................ 302 Eryrine phylogeny ................. 306 Character descriptions ............... 306 Other variation ................ -

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care Sheets Are Often An

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care sheets are often an excellent starting point for learning more about the biology and husbandry of a given species, including their housing/enclosure requirements, temperament and handling, diet , and other aspects of care. MAHS itself has created many such care sheets for a wide range of reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates we believe to have straightforward care requirements, and thus make suitable family and beginner’s to intermediate level pets. Some species with much more complex, difficult to meet, or impracticable care requirements than what can be adequately explained in a one page care sheet may be multiple pages. We can also provide additional links, resources, and information on these species we feel are reliable and trustworthy if requested. If you would like to request a copy of a care sheet for any of the species listed below, or have a suggestion for an animal you don’t see on our list, contact us to let us know! Unfortunately, for liability reasons, MAHS is unable to create or publish care sheets for medically significant venomous species. This includes species in the families Crotilidae, Viperidae, and Elapidae, as well as the Helodermatidae (the Gila Monsters and Mexican Beaded Lizards) and some medically significant rear fanged Colubridae. Those that are serious about wishing to learn more about venomous reptile husbandry that cannot be adequately covered in one to three page care sheets should take the time to utilize all available resources by reading books and literature, consulting with, and working with an experienced and knowledgeable mentor in order to learn the ropes hands on. -

Class: Amphibia Amphibians Order

CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS Anniella (Legless Lizards) ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) ___Southern Alligator Lizard ............................ RI,DE – fD Bufo (True Toads) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES Bufo (True Toads) ___California (Western) Toad.............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ___California (Western) Toad ............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) Anniella ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN (Legless Lizards) Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) ___Rosy Boa ............................................ DS,CH,RO – fN HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN COLUBRIDAE (Colubrid Snakes) ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN ___Pacific Chorus Frog ....................... AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN Arizona (Glossy Snakes) ___Pacific Chorus Frog ........................AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Glossy Snake ........................................... DS,SA – cN Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) RANIDAE (True Frog Family) -

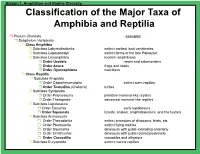

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Sensitive Species of Snakes, Frogs, and Salamanders in Southern California Conifer Forest Areas: Status and Management1

Sensitive Species of Snakes, Frogs, and Salamanders in Southern California Conifer Forest Areas: Status and Management1 Glenn R. Stewart2, Mark R. Jennings3, and Robert H. Goodman, Jr.4 Abstract At least 35 species of amphibians and reptiles occur regularly in the conifer forest areas of southern California. Twelve of them have some or all of their populations identified as experiencing some degree of threat. Among the snakes, frogs, and salamanders that we believe need particular attention are the southern rubber boa (Charina bottae umbratica), San Bernardino mountain kingsnake (Lampropeltis zonata parvirubra), San Diego mountain kingsnake (L.z. pulchra), California red-legged frog (Rana aurora draytonii), mountain yellow-legged frog (R. muscosa), San Gabriel Mountain slender salamander (Batrachoseps gabrieli), yellow-blotched salamander (Ensatina eschscholtzii croceater), and large-blotched salamander (E.e. klauberi). To varying degrees, these taxa face threats of habitat degradation and fragmentation, as well as a multitude of other impacts ranging from predation by alien species and human collectors to reduced genetic diversity and chance environmental catastrophes. Except for the recently described San Gabriel Mountain slender salamander, all of these focus taxa are included on Federal and/or State lists of endangered, threatened, or special concern species. Those not federally listed as Endangered or Threatened are listed as Forest Service Region 5 Sensitive Species. All of these taxa also are the subjects of recent and ongoing phylogeographic studies, and they are of continuing interest to biologists studying the evolutionary processes that shape modern species of terrestrial vertebrates. Current information on their taxonomy, distribution, habits and problems is briefly reviewed and management recommendations are made. -

Wildlife Item 09 CGR-479

#7 C STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Wildlife Diversity Division 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Ste 120 • Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 688-1500 Fax (775) 688-1697 MEMORANDUM July 23, 2018 To: Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners, County Advisory Boards to Manage Wildlife, and Interested Publics From: Jennifer Newmark, Administrator, Wildlife Diversity Division Title: Commission General Regulation 479, Scientific Name Change of the Rosy Boa, a Protected Reptile, LCB File No. 152-18 – For Possible Action/Public Comment Allowed Description: The Commission will consider and may take action to change the scientific name of the rosy boa, protected under Nevada Administrative Code 503.080, from Lichanura trivirgata, to Lichanura orcutti due to recent studies that have updated the taxonomy of the species. Summary: A genetics study in 2008 by Woods et al. split the rosy boa into two distinct species – the three- lined boa (Lichanura trivirgata) and the rosy boa (Lichanura orcutti). This split was formally recognized in 2017 by the Committee on Standard English and Scientific Names by the Society of the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Three-lined boas, Lichanura trivirgata, occur in Baja California, Southern Arizona and Sonora Mexico, while the rosy boa, Lichanura orcutti occur in Nevada, parts of California and northern Arizona. As currently listed, NAC 503.080 protects the three-lined boa, Lichanura trivirgata, a species that does not occur in Nevada. Recognizing the taxonomic change will ensure the species presumed to occur in Nevada, the rosy boa (Lichanura orcutti) will remain protected. The Department is recommending the Commission change the name of the rosy boa listed under NAC 503.080 from Lichanura trivirgata to Lichanura orcutti to protect the correct native species occurring in the state. -

Monitoring Results for Reptiles, Amphibians and Ants in the Nature Reserve of Orange County (NROC) 2002

Monitoring Results for Reptiles, Amphibians and Ants in the Nature Reserve of Orange County (NROC) 2002 Summary Report Prepared for: The Nature Reserve of Orange County – Lyn McAfee The Nature Conservancy – Trish Smith U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WESTERN ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH CENTER Monitoring Results for Reptiles, Amphibians and Ants in the Nature Reserve of Orange County (NROC) 2002 By Adam Backlin1, Cindy Hitchcock1, Krista Pease2 and Robert Fisher2 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WESTERN ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH CENTER Annual Report Prepared for: The Nature Reserve of Orange County The Nature Conservancy 1San Diego Field Station-Irvine Office USGS Western Ecological Research Center 2883 Irvine Blvd. Irvine, CA 92602 2San Diego Field Station-San Diego Office USGS Western Ecological Research Center 5745 Kearny Villa Road, Suite M San Diego, CA 92123 Sacramento, California 2003 ii U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, SECRETARY U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, or brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information, contact: Center Director Western Ecological Research Center U.S. Geological Survey 7801 Folsom Blvd., Suite 101 Sacramento, CA 95826 iii Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 1 Research Goals .................................................................................................................. -

Critter Twitter June 6-10 & July 11-15, 2011

Critter Twitter June 6-10 & July 11-15, 2011 Monday-Visual Communication Time K-1st Grade 2nd-3rd Grade 4th-6th Grade 8:45 Check in Check in Check in Talk about how animals Talk about how animals Talk about how animals 9:00 communicate visually communicate visually communicate visually Keeper talk & feeding-BRC 9:30 Snack aviary Game-Clothespin Tag 10:00 Game-Zookeeper Snack AP-bearded dragon & ferret 10:30 AP-milk snake and opossum Game-Clothespin Tag Snack Craft-trace body on butcher paper, add a visual 11:00 Craft-Nature Notebook Craft-Nature Notebook communication adaptation Draw picture of animal who Draw picture of animal who Zoo tour-look for visual 11:30 communicates visually communicates visually communication signs 11:50 Plaza-1/2 day campers depart Plaza-1/2 day campers depart Plaza-1/2 day campers depart 12:00 Lunch at Treetops Lunch at Treetops Lunch at Treetops 12:45 Clean up/Restroom break Clean up/Restroom break Clean up/Restroom break 1:00 AP-bearded dragon & ferret Game- Game-Clump 1:30 Game-Clump AP-bearded dragon & ferret BTS-Giraffe 2:00 Snack Snack AP-milk snake and opossum Craft-trace body on butcher paper, add a visual 2:30 BTS-Giraffe communication adaptation Snack 3:00 Craft-Giraffe headband BTS-Giraffe Craft-Nature Notebook Draw picture of animal who 3:30 Game-Rainbow Tag Game-Rainbow Tag communicates visually 3:45 Plaza for pick-up Plaza for pick-up Plaza for pick-up 4:00- 5:30 Extended day care Extended day care Extended day care Tuesday-Auditory Communication Time K-1st Grade 2nd-3rd Grade 4th-6th Grade 8:45