Factors Influencing Listener Preference for Music Therapistsâ•Ž

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

ORGANIZATION: Contact: Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza Foundation Colleen Debler 2100 Thousand Oaks Blvd. [email protected] Thousand Oaks, CA 91362 805-449-2765 NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza Foundation Sept. 2, 2014 Bob Biery Rising Singer/Songwriter Mary Lambert President Performs at the Civic Arts Plaza Jerry Miller Vice President (Thousand Oaks, CA) – Mary Lambert, the featured vocalist and songwriter on Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’ award-winning song “Same Love”, makes her only southern California appearance at the Scherr John Bradley Forum on Friday, September 26, 2014 at 8:30 pm. Judith Linton Lambert has been a singer, songwriter, composer and spoken word artist in her native Seattle for the past six years. A competitor in Russell Simmons “Brave New Voices” (HBO) International Competition David Mead in 2008, Lambert is Seattle’s 2011 Grand Poetry Slam Champion and the 2012 Northwest Regional Slam winner. ◊ ◊ ◊ As one of the biggest music revelations of 2013, Lambert went from juggling several jobs to playing in front of thousands of people, touring the country, and performing live on national television on such hugely popular primetime and late night shows as The Ellen DeGeneres Show, VH1 and The Colbert Barry McComb Report. “Same Love” has sold over a million copies in the US alone, peaking at number 11 on The Executive Director Billboard Hot 100. Stacy Park Lambert has been lighting up the airwaves at Adult Top 40 stations nationwide with her single “She Associate Director Keeps Me Warm,” which has climbed into the Top 20. The track is featured on her debut EP, Welcome to the Age of My Body, which was released in December and has earned rave reviews. -

1 United States District Court Eastern District Of

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA PAUL BATISTE d/b/a ARTANG PUBLISHING, LLC CIVIL ACTION V. NO. 17-4435 RYAN LEWIS, ET AL. SECTION "F" ORDER AND REASONS Before the Court is the defendants’ motion to dismiss pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). For the following reasons, the motion is DENIED. Background A New Orleans jazz musician accuses an internationally famous hip-hop duo of copyright infringement of eleven original songs. This litigation followed. Paul Batiste is a member of The Batiste Brothers Band, a New Orleans jazz band founded in 1976. Batiste also owns Artang Publishing LLC. Beginning in 1997 through 2002, Batiste composed several original songs, entitled Hip Jazz, Kids, Starlite Pt. 1, World of Blues, Love Horizon, Tone Palette, My Bad, Salsa 4 Elise (Fur Elise), Drowning in my Blues, Sportsman’s Paradise, and Move That Body. Batiste has registered each song with the United States Copyright Office. Ryan Lewis and Ben Haggerty form the hip-hop duo known as “Macklemore and Ryan Lewis.” The duo has achieved international 1 stardom, and is best known for their singles “Thrift Shop” and “Can’t Hold Us,” which were both one of the most popular songs in the United States and Australia after their releases in 2012 and 2016.1 They also received several Grammy awards, including those for best new artist, best album, and best rap performance for their single, Thrift Shop. On May 1, 2017, Batiste2 sued Ryan Lewis and Ben Haggerty for infringing on his copyrights by using unauthorized samples and copying elements of the eleven original songs listed above in the composition of their songs Thrift Shop, Can’t Hold Us, Need to Know, Same Love, and Neon Cathedral. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Mary Lambert: Spreading the Love Call Singer-Songwriter Mary Lambert a Missionary for Self-Acceptance

Mary Lambert: Spreading the love Call singer-songwriter Mary Lambert a missionary for self-acceptance. When it comes to bipolar disorder, body-image and more, she won’t take shame for an answer. By Stephanie Stephens Mary Lambert doesn’t care if the world knows her secrets. She recites them, sings them, and lives them large with a candid, “this is really me” demeanor that endears her to legions of loyal fans. Along the way she sets a powerful example of how to steadfastly love yourself even when you’ve been programmed not to—because you’re not a size 4, because you have a mental illness, because people in your life treat you as if you’re worthless. Hearing her hit single “Secrets” for the first time often prompts a double-take: “Did she really sing that?” Yes, she did, just like this: I’ve got bi-polar disorder My sh*** not in order The bubbly and disarming multi-hyphenate (singer-songwriter, poet, and spoken-word artist) remembers telling her friends how she was going to start the song. Aghast, they asked her, “Are you sure you want to do that?” She shot back without hesitation, “Yes!” “Then I woke up the next morning with a ‘truth hangover,’” laughs Lambert, on break from a U.S. tour with the Irish band The Script and singer/songwriter Colton Avery. “Being vulnerable is essential to my music, the way I function and love, and how I connect with people,” the 26-year-old says. “Vulnerability is the key to empathy, but it is also a double-edged sword. -

THESIS Submitted As Partial Fulfillment of Requirement for the Sarjana Sastra Degree of the English Department Faculty of Cultural Sciences Sebelas Maret University

perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id THE REPRESENTATION OF HOMOSEXUALITY IN AMERICAN MUSIC VIDEOS IN THE ERA OF LEGALIZATION OF SAME-SEX MARRIAGE RELEASED BETWEEN 2012-2014 THESIS Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of Requirement For the Sarjana Sastra Degree of the English Department Faculty of Cultural Sciences Sebelas Maret University By Isna Ardyani Fataya C1313008 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURAL SCIENCES SEBELAS MARET UNIVERSITY 2016 commit to user iii perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user iv perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user v perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id PRONOUNCEMENT Name : Isna Ardyani Fataya Number : C1313008 I sincerely certify that this thesis entitled The Representation of Homosexuality in American Music Videos in the Post-Legalization of Same-Sex Marriage Released Between 2012-2014 is my original work. It is not a plagiarism nor written by others. Any materials and previous studies used as reference are written in direct quotation or in paraphrase and cited properly. I am fully responsible for the pronouncement. If it is proven to be wrong, I am willing to take any responsible actions given by the Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Sebelas Maret University. Surakarta, 18 July 2016 Isna Ardyani Fataya commit to user vi perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id MOTTOS “Successful people are not lucky people. They are fighters, believers and thinkers. Don’t wipe out all the battles they’ve passed through by saying they are lucky” -Budi Waluyo- “It always seems impossible until it’s done” -Nelson Mandela- “I will keep moving forward. -

The Recording Academy®

® The Recording Academy 3030 Olympic Blvd. • Santa Monica, CA 90404 www.grammy.com JAY Z LEADS NOMINATIONS WITH NINE; KENDRICK LAMAR, MACKLEMORE & RYAN LEWIS, JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE, AND PHARRELL WILLIAMS EACH EARN SEVEN; DRAKE AND BOB LUDWIG EACH GARNER FIVE SARA BAREILLES, DAFT PUNK, KENDRICK LAMAR, MACKLEMORE & RYAN LEWIS, AND TAYLOR SWIFT VIE FOR ALBUM OF THE YEAR AT THE 56TH ANNUAL GRAMMY AWARDS® JAN. 26, 2014, LIVE ON CBS LOS ANGELES (Dec. 06, 2013) — Nominations for the 56th Annual GRAMMY Awards® were announced tonight by The Recording Academy® and reflected one of the most diverse years with the Album Of The Year category alone representing the rap, pop, country and dance/electronica genres, as determined by the voting members of The Academy. Once again, nominations in select categories for the annual GRAMMY Awards were announced on primetime television as part of "The GRAMMY® Nominations Concert Live!! — Countdown To Music's Biggest Night®," a one-hour CBS entertainment special broadcast live from Nokia Theatre L.A. LIVE. The 56th Annual GRAMMY Awards will be held on "GRAMMY Sunday," Jan. 26, 2014, at STAPLES Center in Los Angeles and once again will be broadcast live in high-definition TV and 5.1 surround sound on CBS from 8 – 11:30 p.m. (ET/PT). For updates and breaking news, please visit The Recording Academy's social networks on Twitter and Facebook. For a complete nominations list, please visit www.grammy.com. Jay Z tops the nominations with nine; Kendrick Lamar, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, Justin Timberlake, and Pharrell Williams each garner seven nods; Drake and mastering engineer Bob Ludwig are up for five awards. -

Q3 Hit Pop Sub-Genre Influences

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Q3 Hit Pop Sub-Genre Influences Overview This report spotlights the individual sub-genres that helped shape the 23 top 10 songs that landed on the Billboard Pop Songs chart during Q3-2013. Typically, these sub-genres fall into one of the following categories: Dance Hip Hop/Rap Rock R&B/Soul Pop Fusion/Other “Other” refers to songs that didn’t fall into one of the primary sub-genre categories detailed above (e.g. Folk, Singer/Songwriter, Dubstep, etc…). In regard to Pop Fusion, this is where more than one primary sub-genre influences a song’s sound. Some recent examples include Country/Folk fusing with EDM (Wake Me Up), Country fusing with Straight-Up Pop and Hip Hop/Rap (Cruise) and Funk, Disco and R&B packaged in a retro manner (Treasure). Q3-2013 HIGHLIGHTS Sub Genre Performance All of the sub-genre categories yielded at least 1 #1 hit except for Dance and Rock. Songs that feature a fusion of sub-genres that define their sound (i.e. more than one) rebounded after a 2 quarter decline and once again accounted for the vast majority of 1 / 35 Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com songs. Hip Hop/Rap was the only category that showed a slight increase in number over the previous quarter in addition to Pop Fusion/Other songs. Dance, Rock and R&B/Soul all declined in number. There were 14 distinct sub-genres that mixed and matched with one another to help shape the sound of the 13 songs that landed in the Pop Fusion/Other category during Q3-2013. -

Whiskey Strings Tour

K k ROCKTOBER 2017 K g VOL. 29 #9 H WOWHALL.ORGk artist, and newly graduated with (Sara Bareilles, Tori Amos) and a Bachelors of Music Composition Benny Cassette (Kanye West) in from Cornish College of the Arts, 2014. Her smash single “Secrets” she had begun to establish herself launched to No. 1 on the Billboard MARY around the Seattle area performing Dance charts, and was certified slam poetry and fusing a talk- RIAA Gold in 2015. The New singing style into her intimate York Times called her debut album performances. She received a “refreshing and severely personal.” LAMBERT phone call from a friend who was All though the success, Mary working with Macklemore and had her inner struggles. Ryan Lewis on their debut album Lambert was raised in an The Heist. Macklemore and Lewis abusive home, attempted suicide IS A were struggling to write a chorus at 17, turned to drugs and alcohol for their new song, a marriage- before being diagnosed with equality anthem called “Same bipolar disorder, and survived Love”. Lambert had three hours multiple sexual assaults throughout BABE to write the hook, and the result her childhood. With that list of was the transcendent and beautiful horrors, you wouldn’t expect Mary chorus to Macklemore & Ryan to be disarmingly joyful, but she (AND SO ARE YOU) Lewis’ triple-platinum hit “Same charms effortlessly, and the effect Love”, which Lambert wrote from on her audience is bewitching. her vantage point of being both a She describes her performances Christian and a lesbian. as, “safe spaces where crying is Writing and singing the hook encouraged.” Mary Lambert says, led to two Grammy nominations “My entire prerogative is about for “Song Of The Year” and connection, about being present, By Maya Vagner Mal Blum. -

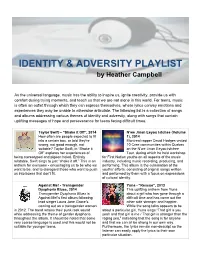

Identity & Adversity Playlist

IDENTITY & ADVERSITY PLAYLIST by Heather Campbell As the universal language, music has the ability to inspire us, ignite creativity, provide us with comfort during trying moments, and teach us that we are not alone in this world. For teens, music is often an outlet through which they can express themselves, where lyrics convey emotions and experiences they may be unable to otherwise articulate. The following list is a collection of songs and albums addressing various themes of identity and adversity, along with songs that contain uplifting messages of hope and perseverance for teens facing difficult times. Taylor Swift – “Shake it Off”, 2014 N’we Jinan Eeyou Istchee (Volume How often are people expected to fit 1), 2014 into a certain box, or told they're Montreal rapper David Hodges visited wrong, not good enough, not 10 Cree communities within Quebec suitable? Taylor Swift, in “Shake it on the N’we Jinan Eeyou Istchee Off” explores her experiences of Tour, during which he held workshop being stereotyped and pigeon holed. Entirely for First Nation youths on all aspects of the music relatable, Swift sings to just “shake it off.” This is an industry, including music recording, producing, and anthem for everyone - encouraging us to be who we performing. This album is the culmination of the want to be, and to disregard those who want to push youths’ efforts, consisting of original songs written us into boxes that don't fit. and performed by them with a focus on expressions of cultural identity. Against Me! - Transgender Yuna - “Rescue”, 2013 Dysphoria Blues, 2014 This uplifting anthem from Yuna Transgender Dysphoria Blues is about a girl who has gone through a Against Me!’s first album following difficult time and has come out the lead singer Laura Jane Grace’s other side stronger and happier. -

Macklemore and Ryan Lewis

CPYU 3(D) REVIEW Song/Video: “Same Love” - Macklemore/Ryan Lewis feat. Mary Lambert By Walt Mueller Background/summary: This song is featured on the debut full-length album, The Heist (released Oc- tober 9, 2012), from Seattle-based rapper Macklemore (29-year-old Ben Haggerty) and producer Ryan Lewis. This single was released in July 2012 and has been picking up steam globally even though it’s a localized call to vote in support of Washington state’s Referendum 74, that would legalize same-sex marriage. The song features a chorus sung by guest artist, Mary Lambert, who is a lesbian. While not a homosexual himself, Macklemore is deeply sympathetic to his two gay uncles. Discover: What is the message/worldview?: The song lyrically unfolds in biopic form as Macklemore begins by telling his own story. As a young boy he fear- fully questioned his sexuality due to his interests in draw- ing and neatness, but his mother told him otherwise: “When I was in the third grade I thought I was gay/’Cause I could draw, an’ my uncle was/And I kept my room straight/I told my mom tears rushing down my face/She’s like ‘Ben you’ve loved girls since before pre-k.” He goes on to lament his acceptance of culturally-defined sexual stereotypes. The video offers a five-and-a-half minute birth-to-death look into the life of a homosexual. The infant is seen growing through boyhood into a sexually-confused adolescence. Knowing he is gay, he struggles to understand and accept himself, including feeling out-of-place at a party (spin-the-bottle) and at a school dance. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Top 40 UPDATE BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS BILLBOARD.BIZ/NEWSLETTER JUNE 6, 2013 | PAGE 1 of 9

MID WEEK Top 40 UPDATE BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS BILLBOARD.BIZ/NEWSLETTER JUNE 6, 2013 | PAGE 1 OF 9 INSIDE Top 40 And Radio Geeks, Unite! The Connected Consumer PAGE 3 RICH APPEL [email protected] What’s With a multitude of entertainment options out there, it’s easy to YOUNGER = HIGHER, LONGER, MORE New At forget that in top 40’s long history, a listener’s favorite station has Who are top 40’s P1s, and how engaged are they in the digital uni- The New never been the only game in town. There was always something verse? According to Edison Research VP Jason Hollins, 60% are Music else a consumer could do. Not to mention there are only so many female, 50% are age 12-24 and 60% 12-34, with an average age of hours in a day, right? 28. This younger skew means a greater Seminar The good news suggested by the HOW TOP 40’S P1s COMPARE TO THE POPULATION level of connectivity compared with PAGE 4 PERSONS TOP 40 Infinite Dial’s study of the format’s 12+ P1s not just other formats but to the 12- P1s—released last week by Edi- AM/FM radio usage in car 84% 88% plus and 12-34 population in general. Macklemore son Research and Arbitron—is that Awareness of Pandora 69% 88% Nearly 80% of P1s have Internet ac- & Ryan Lewis there seems to be plenty of room— Having a profile on any social network 62% 82% cess and use Wi-Fi, and one-third own and time—for all players.