Paan Leaves Are Counted Several Times in Front of Potential Buyers (Schütte 2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

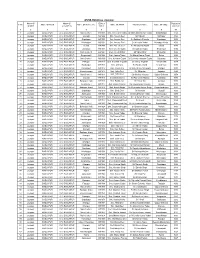

ASHA Database Jaunpur Name of Name of ID No.Of Population S.No

ASHA Database Jaunpur Name Of Name Of ID No.of Population S.No. Name Of Block Name Of Sub-Centre Name Of ASHA Husband's Name Name Of Village District CHC/BPHC ASHA Covered 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center I 3801001 Smt. Amreesha Yadav Sri Mahendra Kumar Yadav Sarokhanpur 1156 2 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Gonauli 3801002 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Rakesh Sarhapur 1302 3 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Gopalapur 3801003 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Subhash Chandra Gopalapur 1000 4 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Mirshadpur 3801004 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Virendra Yadav Muradpur Kotila 1089 5 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Merha 3801005 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Ramashray Nawik Gaura 1000 6 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Dandawa 3801006 Smt. Aneeta Gupta Sri Badelal Gupta Khalishpur 1094 7 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center II 3801007 Smt. Aneeta Kahar Sri Vijay Kahar Bhaluahin 1000 8 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Singramau II 3801008 Smt. Aparna Tiwari Sri Manoj Kumar Tiwari Bahur 1000 9 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center I 3801009 Smt. Archana Gupta Sri Subhash chandra Gupta Sultanpur 1108 10 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Fattupur 3801010 Smt. Archana Trigunait Sri Manoj Trigunait Vithua Kala 1024 11 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Hariharpur 3801011 Smt. Arti Devi Sri Harish chand Kevtali Kala 1000 12 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Ramanipur 3801012 Smt. Aruna Devi Sri Rakesh Kumar Gupta Rautpur 1000 13 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Ghanshyampur 3801013 Smt. Asha Devi Sri Sikandar Jagatpur 1299 14 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center I 3801014 Smt. -

Junior Research Fellowships (Ongoing)

JUNIOR RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS (ONGOING) 1. Tamanna, 6/50 Vijay Nagar, Double Storey, Delhi, Delhi, 110009, Proposal Entitled ‘Urban Experience in Indo-Gangetic divide in Post Harrapan Phase’. 2. Heena, A-499, Nabi Karim Paharganj, New Delhi, Delhi, 110055, Proposal Entitled ‘The Military and Civil Administration of Delhi During the Period of Rebellion, 1857’. 3. Praveen Ashiya, Near New Bus Stand, Mahadev Colony, Ward No.-22 Balotra, Barmer, Rajasthan, 344022, Proposal Entitled ‘बंकिदास िा राजनैतिि एवं साहित्यिि अवदान’. 4. Manish Kumar Singh, 68, Gorkah Pandey Hostel, M.G.A.H.V., Wardha, Maharashtra, 442001, Proposal Entitled ‘औपतनवेशिि उयिर भारि कि महिला ववषिि हिंदी पत्रििाओं मᴂ स्त्िी ववमषष 1910-1948’. 5. Ashok Choudhary, Behind Choudhary Hotel Bhatti Ki Bhawri, Main Chopasni Road, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, 342008, Proposal Entitled ‘जोधपुर रा煍ि िी स्त्थापथ्िा िला – एि ऐतििाशसि अध्ििन िवेशलओं िथा चथाररिां िे वविेष संदभष मᴂ’. 6. Sreenivas Theegala, Room No: 24, VRSRS Hostel, Vidyaranyapuri, Kakatiya University,, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh, 506009, Proposal Entitled ‘Rituals and Festivals of Madiga Communities in Telangana State - A Study’. 7. Pal Joeeta Jayantkumar, 104/III Yamuna Hostel, JNU, Delhi, Delhi, 110067, Proposal Entitled ‘The Body in Death in Early Buddhism: (Circa 4th Century BCE to 4th Century CE)’. 8. Irfan Ahmed, S S Hall South Room No. 36, Aligarh, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, 202002, Proposal Entitled ‘Economic History of Ancient India from 200BC to 300AD’. 9. Aditi Singh, Room #151, Koyna Hostel, JNU, New Campus, New Delhi, Delhi, 110067, Proposal Entitled ‘Codifying Performances: Sanskrit Sastras and Plays (C.2nd -6th Centuries CE)’. -

Varanasi (UTTAR PRADESH)

PURVANCHAL VIDYUT VITARAN NIGAM LTD. SCHEME FOR HOUSEHOLD ELECTRIFICATION DISTRICT : Varanasi (UTTAR PRADESH) DEEN DAYAL UPADHYAYA GRAM JYOTI YOJANA Table of Contents Sl.No. Format No. Name Page No. 1 A General Information 1 2 A(I) Brief Writeup 2 3 A(II) Minutes 2 4 A(III) Pert Chart 2 5 A(IV) Certificate 2 6 A(V) Basic Details of District 2 7 A(VI) Abstract : Scope of Work & Estimated Cost 4 8 A(VII) Financial Bankability 33 9 B Electrification of UE villages 35 10 B(I) Block-wise coverage of villages 36 11 B(II) Villagewise/Habitation wise coverage 37 12 B(III) Existing Habitation Wise Infrastructure 37 13 B(IV) Village Wise/Habitation Proposed Works 37 14 B(V) Existing REDB Infrastructure 37 15 B(VI) Block-Wise Substation 39 16 B(VII) Feederwise DTs 40 17 C Feeder Segregation 45 18 C(I) Details of New 11 KV or 22 KV Lines 46 19 C(II) Works Proposed Under Feeder Separation 49 20 D Connecting unconnected RHHs 119 21 D(I) Block-wise coverage of villages 120 22 D(II) Villagewise/Habitation wise coverage 121 23 D(III) Existing Habitation Wise Infrastructure 177 24 D(IV) Village Wise/Habitation Proposed Works 238 25 D(V) Existing REDB Infrastructure 346 26 D(VI) Block-Wise Substation 348 27 D(VII) Eligibility for Augmentation of Existing 33/11 KV Substations 349 28 D(VIII) Feederwise DTs 363 29 E Metering 368 30 E(I) DTR Metering 369 31 E(II) Consumer Metering 416 32 E(III) Feeder Metering 419 33 F System Strengthening and Augmentation 420 34 F(I) Block-Wise Substation 421 35 F(II) New 33 (or 66) KV REDB Works Proposed 422 36 F(III) Proposed -

Downloaded from सी�नयर �लट OBC डॉ啍यूम�ट वे�र�फकेशन के �लए �त�थ �नधा셍रण स�हत Letter Number 7201 Date 01-10-2019 S.NO

सी�नयर �लट GENERAL डॉ啍यूम�ट वे�र�फकेशन के �लए �त�थ �नधा셍रण स�हत Letter number 7201 date 01-10-2019 S.N Name Fname PAddress i=kad fnukad cqykok frfFk O. GENERAL 1 SUBHAM ARVIND SINGH WARI,HAMIDPUR,KADIPUR,SULTAN 7202 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SINGH PUR Pin.228145 (UP) 2 Sarvesh shukla raju Chandra Rampur Kotwa lalgopalganj kunda 7203 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 shukla Pratapgarh 3 RISHIKESH PREM KISHORE 4121, Chowk kaseru walan pahar 7204 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 ganj new delhi:110055 4 SHUBHAM RAJENDRA SINGH vill-post- Abhaypur Dist Fatehpur 7205 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SINGH pin code 212665 5 Vinay tiwari Ram prakash Village/post loyabadshahpur 7206 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 tiwari district etah uttarpradesh 207001 6 SAURABH DIXIT ANIL KUMAR shiv shakti public school durga 7207 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 DIXIT nagar nagla kishan lal tedi bagiya agra 7 MANISH DEV SHIV KUMAR VILL-POST-ABHAYPUR DIST- 7208 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 GAUTAM SINGH DownloadedFATEHPUR UTTAR PRADESH from PIN- 212665 8 KULDIP BRAJESH SHARMA MOH.www.upsrtc.com HANUMAN NAGAR 7209 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SHARMA FATEHABAD TEHSIL- FATEHABAD DIST- AGRA UP 283111 सी�नयर �लट GENERAL डॉ啍यूम�ट वे�र�फकेशन के �लए �त�थ �नधा셍रण स�हत Letter number 7201 date 01-10-2019 S.N Name Fname PAddress i=kad fnukad cqykok frfFk O. GENERAL 9 SHIVAM HANUMANT VILL GARHI DALEL POST GARHI 7210 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 CHAUHAN SINGH CHAUHAN RAMDHAN DIST ETAWAH PINCODE 206245 10 NISHANT JAGMEHAR Village- Babupura 7211 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SHARMA SHARMA Post- Nanauta District- Saharanpur Pin- 247452 11 DEEPAK SARVESH KUMAR PURANA -

Visual Foxpro

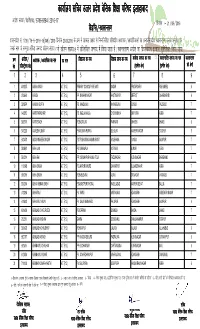

dk;kZy; lfpo mRrj izns'k csfld f'k{kk ifj"kn bykgkckn vkns'k la[;k@cs0f'k0i0@6786-6864 / 2016-17 fnukad %& 21@08@2016 [email protected] 'kklukns'k la- 1739@79&5&2016&15¼149½@2010 fnukad 23-06-2016 ds Øe esa rRdky izHkko ls fuEufyf[kr ifj"knh; v/;kid@v/;kfidkvksa dk vUrtZuinh; LFkkukUrj.k muds vuqjks/k ij muds uke ds lEeq[k vafdr tuin dkWye la[;k 7 ls dkWye la[;k 8 esa mfYyf[kr tuin esa fd;k tkrk gSA LFkkukUrj.k vkns'k dk fØ;kUo;u rRdky lqfuf'pr fd;k tk;A Øze vkosnu@ v/;kid @v/;kfidk dk uke in uke fo|ky; dk uke fodkl [k.M dk uke dk;Zjr tuin dk uke LFkkukUrfjr tuin dk uke LFkkukUrj.k la0la0la0 jftLVªs'ku la0 ¼xzkeh.k {ks=½ ¼xzkeh.k {ks=½ dh Js.kh 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 4316237 AABHA SINGH A.T.(P.S.) PRIMARY SCHOOL PURE ANTI SADAR PRATAPGARH RAE BARELI 6 2 0706562 AABIDA A.T.(P.S.) P.P. MAKHAN NAGAR HASTINAPUR MEERUT SAHARANPUR 6 3 5313974 AAKASH GUPTA A.T.(P.S.) P.S. KHADAUA II NAWABGANJ GONDA FAIZABAD 7 4 1405312 AARTI PARASHAR A.T.(P.S.) P.S. NAGLA MAULA CHOUMUNHA MATHURA AGRA 7 5 3902176 AARTI SINGH A.T.(P.S.) PS BAGRAUNI PANWARI MAHOBA JHANSI 6 6 3402203 AAWESH KUMAR A.T.(P.S.) P.HANUMAN PURWA BILHAUR KANPUR NAGAR SITAPUR 5 7 5324073 ABDUR RAHEEM ANSARI A.T.(P.S.) P.S.TRIBHUWAN NAGAR GRANT MUJEHANA GONDA JAUNPUR 7 8 0309961 ABHA JAIN A.T.(P.S.) P S SIKKAWALA KOTWALI BIJNOR AGRA 7 9 5902114 ABHA RAI A.T.(P.S.) P P USHMANPUR NAUKA TOLA FAZILNAGAR KUSHINAGAR BARABANKI 6 10 1101845 ABHA SINGH A.T.(P.S.) PS JANIPUR KHURD SHIKARPUR BULANDSHAHR AGRA 7 11 6812786 ABHA SINGH A.T.(P.S.) PS BABUSARAI AURAI SR NAGAR VARANASI 7 12 3302464 ABHAY KUMAR SINGH A.T.(P.S.) P,SAMASTPUR NYORAJ RASULABAD KANPUR DEHAT BALLIA 7 13 6122894 ABHAYRAJ A.T.(P.S.) P.V. -

Not Recommended List of Dr D. S. Kothari Postdoctoral

University Grants Commission 56th List of Unsuccessful Candidates for Dr. D. S. Kothari Postdoctoral Fellowship (June 20, 2017) Sr. No. Form No. Name and address BL/16-17/0365 Dr. Sruthi D. 1. Female Cherukuniyil, Vakayad, Naduvannur OPEN Kozhikode:673614, Kerala Dr. Nitin Pal Kalia BL/16-17/0376 VPO Paroul, Via Rehan 2. Male Tehsil Fatehpur OPEN Kangra:176022, Himachal Pradesh Dr. Archana Kumari BL/16-17/0400 Vidya Nagar, Road No-1 3. Female Harmu, Ranchi,834012 OPEN Jharkhand Dr. R. Karthik Raja BL/16-17/0402 Department of Biotechnology 4. Male Periyar University OBC Salem :636011, Tamilnadu BL/16-17/0411 Dr. Bhaskar Reddy 5. Male 66, Shahpur, PO.- Baragaon OBC Varanasi:221204, Uttar Pradesh Dr. Amrina Shafi BL/16-17/0412 Biotechnology Division 6. Female Kashmir University OPEN Srinagar:190006, Kashmir Dr. Shampa Chanda BL/16-17/0423 Flat No.-202, Genesis Apartment 7. Female Dasapalla Layout, Endada OPEN Visakhapatnam:530045, Andhra Pradesh Dr. Jhuma Biswas BL/16-17/0424 C/o. Amit Kr. Mondal 8. Female Green Village, Uchchhepota, Sonarpur SC South 24 Parganas Kolkata:700150, West Bengal BL/16-17/0425 Dr. Usha Yadav 9. Female 40, Teekli OBC Gurgaon:122101, Haryana Dr. Nitesh Kumar Khandelwal Lab. No. 101, School of Life Sciences BL/16-17/0434 Jawaharlal Nehru University 10. Male New Delhi:110067, Delhi OPEN Page 1 of 14 Dr. Menka BL/16-17/0436 Q. No. 3178, Sector 12 B 11. Female Bokaro Steel City:827012, Jharkhand OBC Dr. Satyam Verma BL/16-17/0438 Department of Botany 12. Male Dr. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 5 1751371 06/11

Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 5 1751371 06/11/2008 DR. (MRS.) SMITA NARAM BUNGALOW NO.31, NEXT TO M.D. BUNGALOW NO.25, ROYAL PALM ESTATE, AAREY COLONY, GOREGAON (EAST), MUMBAI-400065 MANUFACTURERS, MARKETERS AND TRADERS. INDIAN NATIONAL Address for service in India/Agents address: USHA A. CHANDRASEKHAR. 3-E1, COURT CHAMBERS, NEW MARINE LINES ROAD, MUMBAI - 400 020. Used Since :01/10/2008 MUMBAI AYURVEDIC MEDICINAL PREPARATIONS, MEDICINAL TOPICAL APPLICATIONS INCLUDED IN CLASS-05 420 Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 5 OSTI-RICH 1758802 02/12/2008 AKESISS PHARMA PRIVATE LIMITED trading as ;AKESISS PHARMA PRIVATE LIMITED RIZWAN ESTATE, PATHADIPALAM, EDAPPALLY, KOCHI - 682 024, INDIA. MANUFACTURER AND MERCHANT BODY INCORPORATE Address for service in India/Attorney address: SENTHILKUMAR BALAKRISHNAN NO.35/16, RAMANUJA NAGAR, KONNUR HIGH ROAD, AYANAVARAM, CHENNAI-600 023. Proposed to be Used CHENNAI PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS, PHARMA AND MEDICINE FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION. 421 Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 5 1912064 21/01/2010 HOECHEST HEALTHCARE LTD 557 CIVIL LINES SOUTH MUZAFFARNAGAR U.P SERVICES INDIAN Address for service in India/Agents address: P. K. ARORA TAJ TRADE MARKS PVT. LTD, 110 ANAND VRINDAVAN SANJAY PLACE AGRA(U.P) Used Since :22/01/2009 DELHI MEDICINAL & PHARMACEUTICALS PREPARATIONS OF ALL KINDS, BEING INCLUDED IN CLASS-05. THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER.. 422 Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 5 ZIMATINIC 1939649 22/03/2010 LALIT JAISWAL KA-72 KAVI NAGAR GHAZIABAD U.P MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS A COMPANY DULY REGISTERED UNDER THE COMPANIES ACT, 1956 Used Since :01/04/1993 DELHI MEDICINAL AND PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS. -

Forms Accepted

✉ eciservicevoter[at]eci[dot]gov[dot]in Welcome : Sub Divisional Magistrate, Sadar Contact Us (/Home/Contact) Log Out (/Home/LogOut) Forms Accepted (/ERO/Index) (/ERO/V (/ERO/V (/ERO/V (/ERO/V (/ERO/V (/ERO/V New Forms (1525) Accepted Forms Accepted by Force From Other EROs Updated Form by Force Requested for Deletion Enrolled SV iewAcceptedByE iewAcceptedByF iewFromOtherER iewUpdatedByF iewRequestForD iewFormsPassF New Form With Signed Document Application Elector Relation State No Service No Gender Name Age Type Relation Name Type Name District Name AC Name Address 1632 15804567F M ASHWANI 22 M KALPANATH YADAV F UTTAR MAU SARWAN (BABHANI KOL) SADAR SARWAN YADAV PRADESH 275101 1898 15804816P M BRIJESH SAROJ 22 M BASANT SAROJ F UTTAR MAU 196 CHOTI BAKWAL SADAR MAU DUMARAW PRADESH 275101 3782 15807624H M MANISH YADAV 21 M BABURAM YADAV F UTTAR MAU SANEGPUR DAKSHIN TOLA BAKHTAWARGA PRADESH 275101 4186 15808091X M VIJAY PRATAP 23 M CHANDRAMA YADAV F UTTAR MAU HILSA SADAR FAIZULLAHPUR 275305 YADAV PRADESH 9000 2998611L M ARVIND KUMAR 35 M RAMASHRAY SINGH F UTTAR MAU NASOPUR MAU UMAPUR 221705 SINGH PRADESH 9435 13632450H M ARUN KUMAR 21 M RAMJEET YADAV F UTTAR MAU THAKURAMANPUR SADAR MAU MAU NATH YADAV PRADESH BHANJAN 275101 9769 3013078M M PANKAJ KUMAR 26 M MARCHHOO YADAV F UTTAR MAU PARMANAND PATTI SADAR THALAIPUR 275 YADAV PRADESH 10267 3006482Y M SATYENDRA 33 M RAJENDRA SINGH F UTTAR MAU RAJANPUR MAU HALDHARPUR 221705 KUMAR SINGH PRADESH 10717 3005958N M RADHE SHYAM 35 M OM PRAKASH SINGH F UTTAR MAU TAJOPUR MAUNATH BANJAN TAJOPUR 275 -

AK Singh 2.Pmd

Current World Enviroment Vol. 2(2), 241-244 (2007) Studies on different soil parameters under investigated areas of Jaunpur District (U.P.) ASHOK KUMAR SINGH1, M. H. ANSARI1, N.P. SINGH², S. K. SINGH³ and A.K. SRIVASTAVA4 1Department of Chemistry, S.G.R.P.G. College, Dobhi, Jaunpur (India) ²Department of Chemistry, T.D.P.G. College, Jaunpur (India) ³Department of Chemistry, U.P. Autonomous College, Varanasi (India) 4Department of Applied Chemistry, U.N.S. Institute of Engineering and Technology V.B.S.P.U. Jaunpur (India) (Received: July 12, 2007; Accepted: September 17, 2007) ABSTRACT The fertility of soil directly influenced by its physico-chemical as well as biotic contaminants. The physical properties like soil separates and texture, structure, weight and density, porosity, permeability, colour etc. chemical contaminants involving organic and inorganic matters and the biological factors like bacteria, fungi, nematodes and other micro-organisms assess the fertility potency of soil. Out of these the physical and the chemical factors are highly significant. In the present investigation an attempt has been made to convert the favourable soil conditions according to the infrastructural environment of the area for farming. Key words: Soil parameters, Fertility, Jaunpur district. INTRODUCTION physico-chemical activity but finger grades play important role in some chemical processes. The present investigation is a part of They are very fertile and have great water holding infrastructural study of the project undertaken. capacity. Such soils are good for agriculture. Soil possesses many characteristics physical The smallest particle of soil is known as clay, having properties1-3 like soil separates and texture, soil diameter range below 0.002mm. -

District Census Handbook, 27-Banaras, Uttar Pradesh

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 1951 BANARAS I)}STRI·CT FOREWORD Several States, including Uttar Pradesh, have been publishing village statistics by districts 'at each census. In 1941 they were, published. in U. P. under the tide "District Census Statistics" with a separate volume for each district. In the I9SI census, when the tabulttion has been more elaborate-than ever in view of the require" ments of the country, the district"wise volume has been expanded into a "District Census, Handbook", which now contains the District Census Tables (furnishing data with break"up for census tracts within the district), the District Index of Non" agricultural Occupations, agricultural statistics from 1901-'02 to 1950"51 and other miscellaneous statistics in addition to t~e usual village population statistics. The village population statistics also are given in an elaborate form giving the division oi the population among eight livelihood classes and other de~ails. 2. It may be added here that ,a separate set of district"wise volumes giving only population figures of rural areas by villages and of urban areas by wards and mohaUas and entitled "District Population Statistics" has already been published. This separate series was necessitated by the urgent requirements of the U. P. Government for elections to local bodies. 3. The number of District Census Handbooks printed so far is fourteen. Special arrangements for speeding up the printing have now been made and it is hoped that the remaining Handbooks will be printed before the end of 1955. RAJESHWARI PRASAD,I.A.S .. RAMPUR: Superintendent} Census Operations} March 31, 1955, Uttar Pradesh. -

In Varanasi Zone

SNo District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Grampanchayat Village Name Contact No 1 Varanasi Varanasi-NIELIT chollapur LANKA CIC_Manish Pandey Chollapur 896088439 2 Varanasi Varanasi varanasi 221011 nuaon (narayanpur) chandrakant singh nuaon 7052995164 3 Varanasi Varanasi1-NIELIT Kashividyapeeth 221011 Amara Amit Singh Sadalpur 7054897777 4 Varanasi Varanasi2-NIELIT kashi vidyapith 221107 Lohta Mohammad Arif Lohta 7054966053 5 Varanasi VARANASI6 Nagar Nigam 221002 Nagar Nigam Sanjay kumar Patel Varunapul 7068235194 6 Varanasi Varanasi1-NIELIT CHIRAIGAON 221007 NEAR HANUMAN MANDIR(R) MUNNA LAL SANDAHA 7068754968 7 Varanasi Varanasi1-NIELIT GAJEPUR(TAKKHU KI BAULI) 221403 GAJEPUR VINAY KUMAR GUPTA GAJEPUR 7068789898 8 Varanasi Chirai gaon Bariyasanpur 221007 Bariyasanpur Atul Kumar singh BARIASANPUR 7071068307 9 Varanasi Varanasi Pindra 221203 nehia to murdi Rohit verma Ghonghari 7071362060 10 Varanasi Varanasi1 Rajatalab 221403 MATUKA Veenit Gupta Matuka 7071788285 11 Varanasi VARANASI6 Nagar Nigam 221002 Vairav Nagra Ashish Singh Raghuvanshi Varuna 7080789189 12 Varanasi Varanasi2-NIELIT KASHI VIDYA PITH 221011 MADHOPUR RAVI KANT YUADAV MADHOPUR 7080795317 13 Varanasi Varanasi1-NIELIT KASHIVIDYA PITH 221108 churamanpur(R) Mustaq khan churamanpur 7080909588 14 Varanasi Varanasi3 Harahua 221105 Chaka Adarsh Kumar Singh Chaka 7252298686 15 Varanasi Varanasi2 Varanasi 221001 SALARPUR Nidhi Devi Salarpur 7266938033 16 Varanasi Varanasi1-NIELIT Saiudaypur(Rural) 221101 Saiudaypur Neeraj Kumar Kanaujia Saiudaypur 7271059533 -

District Census Handbook, Mau, Part XII-A & B, Vol-II, Series-10, Uttar

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES-10 UTTAR PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Part - A & B MAU VOLUME - II VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS UTTAR PRADESH LUCKNOW Contents Page Foreword XI Preface XIII ,Acknowledgemen t XIV VOLUME -I District Highlights - 2001 Census XVI Important Statistics in the District XVII Ranking. of Tahsils in the District XIX Statement-l Name of the headquarters of district/tahsil, their rural-urban status XX and distance from district headquarters, 200 I. Statement-2 Name of the headquarters of district/C D block their rural-urban status XX and distance from district headquarters, 2001. Statement-3 Population of the district at each census from 1901 to 2001. XXI Statement-4 Area, n.umber of villages/towns and population in district and tahsil, 2001. XXII Statement-5 C 0 Blockwise number of villages and rural population, 2001. XXIII Statement-6 Population of Urban Agglomerations/towns, 2001. XX III Statement-7 Villages with population of 5,000 and above at C D Block level as per 2001 census and amenities available. XXIV rStatement-8 Statutory towns with population less than 5000 as per 2001 census and amenities available. xxv Statement-9 Houseless and Institutional popUlation of tahsils, rural and urban, 2001. XXV Analytical Note (i) History and scope of the District Census Handbook 2 (ii) Brief history of the district 2 (iii) Administrative set-up 3 (iv) Physical features 4 (1) Location and size 4 (2) Physiography 4 (3) Drainage 5 (4) Climate 5 (5) Natural Economic Resources 5 (v) Census Concepts 9 (vi) Non-Census Concepts 19 (vii) 200 I Census findings-Population, its distribution etc.