Advanced Financial Statements Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Intrinsic Value of an Enterprise Determined by Means of the FCFE Tool

sustainability Article The Intrinsic Value of an Enterprise Determined by Means of the FCFE Tool Veronika Jezkova, Zuzana Rowland, Veronika Machova * and Jan Hejda Institute of Technology and Business, School of Expertness and Valuation, Okruzni 517/10, 37001 Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic; [email protected] (V.J.); [email protected] (Z.R.); [email protected] (J.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +778-714-680 Received: 14 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: This paper deals with the determination of the intrinsic value of the company Seznam.cz, a.s. using discounted cash flow. Specifically, it is concerned with determining the value of the business from the perspective of the company’s shareholders. The Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) method is chosen for analysis and determination of the value. According to this method, the specific FCFE values are discovered. However, the enterprise value must also be analyzed on the basis of other key indicators, such as financial leverage, the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) method, or the net present and future value of the FCFE. This is especially important so that the results can be put into mutual relations and a sufficient representative value of the FCFE results can be achieved. Input values stem from the company’s annual reports. From the results of the mentioned methods and indicators, it was found that the value of the FCFE is quite high, which means that the capital used is used appropriately. Based on the result of the continuing value of the FCFE, it can be said that the company’s intrinsic value is at a very good level. -

Reorganization Value What It Is and Isn't

VALUATION 2016 Q3 This principle is illustrated as follows from an accounting Reorganization Value: balance sheet perspective: What It Is…..and Isn’t Assets = Liabilities + Equity BORIS J. STEFFEN, CDBV Assets are comprised of operating and non-operating RSM US LLP assets, while liabilities combine operating liabilities and The importance of reorganization value is that it is perhaps long-term interest-bearing debt. Consequently, the the measure that determines whether a debtor will be able accounting balance sheet equation comingles operating to reorganize, and the value of the reorganized debtor liabilities and financing sources on the right side of the that is distributable to holders of interests and claims. balance sheet: Nevertheless, reorganization value is not specifically Assets = Operating Liabilities + Debt + Equity defined in the Code or in case law, other than by reference to the general principle that a debtor should be valued Rearranging the formula by moving operating liabilities based on the capitalization of its expected future earnings. to the left side of the equation leads to the measure of Bankruptcy courts must therefore determine the “extent invested capital. The left side calculation shows how much and method of inquiry necessary for a valuation based on capital has been deployed by the firm; the right side earning capacity….dependent on the facts of each case.”1 calculation shows how much financing has been provided Courts determine reorganization value by reference to the by creditors and investors: debtor’s enterprise value based on the fair value standard, Assets – Operating Liabilities = Debt + Equity = Invested going concern premise, and present value of expected Capital future cash flows and/or market multiples. -

Free Cash Flow to Equity Discount Models

ch14_p351-379.qxd 12/5/11 2:14 PM Page 351 CHAPTER 14 Free Cash Flow to Equity Discount Models he dividend discount model is based on the premise that the only cash flows re- Tceived by stockholders are dividends. Even if we use the modified version of the model and treat stock buybacks as dividends, we may misvalue firms that consis- tently fail to return what they can afford to their stockholders. This chapter uses a more expansive definition of cash flows to equity as the cash flows left over after meeting all financial obligations, including debt payments, and after covering capital expenditure and working capital needs. It discusses the rea- sons for differences between dividends and free cash flows to equity, and presents the discounted free cash flow to equity model for valuation. MEASURING WHAT FIRMS CAN RETURN TO THEIR STOCKHOLDERS Given what firms are returning to their stockholders in the form of dividends or stock buybacks, how do we decide whether they are returning too much or too lit- tle? We measure how much cash is available to be paid out to stockholders after meeting reinvestment needs and compare this amount to the amount actually re- turned to stockholders. Free Cash Flows to Equity To estimate how much cash a firm can afford to return to its stockholders, we begin with the net income—the accounting measure of the stockholders’ earnings during the period—and convert it to a cash flow by subtracting out a firm’s reinvestment needs. First, any capital expenditures, defined broadly to include acquisitions, are subtracted from the net income, since they represent cash outflows. -

The Impact of Free Cash Flow on Market Value of Firm

Global Review of Accounting and Finance Vol. 5. No. 2. September 2014. Pp. 56 – 63 The Impact of Free Cash Flow on Market Value of Firm Abdul Nafea Al Zararee* and Abdulrahman Al-Azzawi** This paper constitutes an attempt to investigate the relationship between Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) and the firm's market value of the pharmaceutical sector of Jordan by using a valuation technique, wherein the rift between theory and practice still need to be accommodated taking in consideration the relationship of FCFE, Net Income, Net Capital Expenditure, Working Capital and Debt Position. This paper uses panel data covering the period 2004-2010. The determination of a company's market value is a difficult decision, taking into account several antagonistic factors, such as risk of debt and capital expenditure, in times when the economic environment in which the company operates is unstable, therefore the choice among the ideal equation of FCF to Equity can affect the market value of the firm as much as profit rate can. The results show that the market values of a firm are assessed by the Free Cash Flow to Equity. Our result is in accordance with the hypothesis that FCF to Equity has significant positive effect on the stock market. Our findings add to the understanding of the determinants of the market value of firms. Keywords: Market Value; Free Cash Flow; Equity 1. Introduction The debate about the Free Cash Flow (FCF) relationship with the market value of a firm has been the core of the finance literature for the previous several decades. -

Finance (21138)

Year 2015-16 Finance (21138) Degree/study: 2014-21138-IBE GRAU Course: 3 Term: first Number of ECTS credits: 5 Hours of student’s dedication: 30 Language or languages of instruction: English Theory Classes Professor: Filippo Ippolito 1. Presentation of the subject This is an introductory course on corporate finance with a focus on capital structure, liquidity and payout policy, and capital budgeting. We first analyze the capital structure decision in a setting of perfect capital markets in which all securities are fairly priced, there are no taxes or transactions costs, and the total cash flows of the firm’s projects are not affected by how the firm finances them. We then examine the impact of taxes and of other frictions on the capital structure decision to explain the observed differences in capital structure across firms and industries. We then shift the attention to liquidity and payout policy and to how these policies are shaped by market imperfections, such as taxes, agency costs, transaction costs, and asymmetric information, just as capital structure is. We discuss why some firms pay dividends and some do not, and why some firms prefer share repurchases. Next, we investigate the complexities of capital budgeting, how to estimate the appropriate cost of capital, and also how the financing decision can affect the cost of capital and cash flows. We introduce the three main methods for capital budgeting with leverage and market imperfections: the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) method, the adjusted present value (APV) method, and the flow-to-equity (FTE) method. Finally, we study how corporations raise equity capital and debt financing in its different forms. -

Free Cash Flow in a DCF – Quick Reference

How to Calculate Free Cash Flow in a DCF – Quick Reference http://breakingintowallstreet.com Free Cash Flow Overview When you’re valuing a company with a DCF analysis, you need to calculate their Free Cash Flow (FCF) to figure out what they’re worth. While “Free Cash Flow” is simple in theory, in practice it has generated more questions on the BIWS site than almost any other topic. I’m going to cover 7 key points about FCF here: 1. What "Free Cash Flow" actually means, and why we use it rather than EBITDA, EPS, or other profitability metrics in a DCF. 2. An outline of how to transform a Cash Flow Statement into a Free Cash Flow calculation. 3. What you do with Working Capital line items, what you include and exclude, and why you add or subtract different items in those calculations. 4. Unlevered vs. Levered Free Cash Flow, and why we normally use Unlevered FCF in a DCF. 5. How to project Free Cash Flow over a 5-year period in a DCF. 6. How to put all these pieces together and calculate FCF via different formulas. 7. Lingering / common questions on how to calculate FCF in a DCF analysis. What “Free Cash Flow” Means and FCF vs. EBITDA vs. EPS “Free Cash Flow” means: “How much cash is this company’s core business generating, on a recurring, predictable basis?” Many companies define Free Cash Flow as: Cash Flow from Operations minus Capital Expenditures (CapEx) (Yes, this is a simplified definition – we’ll get into the more detailed ones in a bit). -

Direccio Financiera II

Year 2014-15 Direccio Financiera II Degree/study: 2013-14- GRAU EMPRESARIAL Course: 3-4 Term: Third Number of ECTS credits: 5 Hours of student’s dedication: 125 Language or languages of instruction: English Professor: Filippo Ippolito 1. Presentation of the subject The primary objective of the course is to improve the knowledge of corporate finance, with particular emphasis on how corporations are financed. We begin by studying how corporations raise equity capital and debt financing in its different forms. We provide an extended example of the initial public offering (IPO) of a real company, Real Networks. We discuss corporate debt instruments and study the case of Hertz’s leveraged buyout (LBO) to illustrate how corporations use debt markets to raise capital. We then analyze of capital structure decisions in a setting of perfect capital markets in which all securities are fairly priced, there are no taxes or transactions costs, and the total cash flows of the firm’s projects are not affected by how the firm finances them. We then examine the impact of taxes and of other frictions on the capital structure decision to explain the observed differences in capital structure across firms and industries. We then shift the attention to payout policy and to how dividend policy is shaped by market imperfections, such as taxes, agency costs, transaction costs, and asymmetric information, just as capital structure is. We discuss why some firms pay dividends and some do not, and why some firms prefer share repurchases. Finally, we investigate the complexities of capital budgeting, how to estimate the appropriate cost of capital, and also how the financing decision can affect the cost of capital and cash flows. -

Dividends and Cash Flows to Equity

Dividends and Cash Flows to Equity 145 ¨ In the strictest sense, the only cash flow that an investor will receive from an equity investment in a publicly traded firm is the dividend that will be paid on the stock. ¨ Actual dividends, however, are set by the managers of the firm and may be much lower than the potential dividends (that could have been paid out) ¤ managers are conservative and try to smooth out dividends ¤ managers like to hold on to cash to meet unforeseen future contingencies and investment opportunities ¨ When actual dividends are less than potential dividends, using a model that focuses only on dividends will under state the true value of the equity in a firm. Aswath Damodaran 145 Measuring Potential Dividends 146 ¨ Some analysts assume that the earnings of a firm represent its potential dividends. This cannot be true for several reasons: ¤ Earnings are not cash flows, since there are both non-cash revenues and expenses in the earnings calculation ¤ Even if earnings were cash flows, a firm that paid its earnings out as dividends would not be investing in new assets and thus could not grow ¤ Valuation models, where earnings are discounted back to the present, will over estimate the value of the equity in the firm ¨ The potential dividends of a firm are the cash flows left over after the firm has made any “investments” it needs to make to create future growth and net debt repayments (debt repayments - new debt issues) ¤ The common categorization of capital expenditures into discretionary and non-discretionary loses its basis when there is future growth built into the valuation. -

Valuation Approaches and Metrics: a Survey of the Theory and Evidence

Foundations and TrendsR in Finance Vol. 1, No 8 (2005) 693–784 c 2005 A. Damodaran DOI: 10.1561/0500000013 Valuation Approaches and Metrics: A Survey of the Theory and Evidence Aswath Damodaran Stern School of Business, New York University, 44 W. 4th Street, 9th Floor, New York, NY10012-1126, [email protected] Abstract Valuation lies at the heart of much of what we do in finance, whether it is the study of market efficiency and questions about corporate gover- nance or the comparison of different investment decision rules in capital budgeting. In this paper, we consider the theory and evidence on valu- ation approaches. We begin by surveying the literature on discounted cash flow valuation models, ranging from the first mentions of the divi- dend discount model to value stocks to the use of excess return models in more recent years. In the second part of the paper, we examine relative valuation models and, in particular, the use of multiples and comparables in valuation and evaluate whether relative valuation mod- els yield more or less precise estimates of value than discounted cash flow models. In the final part of the paper, we set the stage for further research in valuation by noting the estimation challenges we face as companies globalize and become exposed to risk in multiple countries. 1 Introduction Valuation can be considered the heart of finance. In corporate finance, we consider how best to increase firm value by changing its investment, financing and dividend decisions. In portfolio management, we expend resources trying to find firms that trade at less than their true value and then hope to generate profits as prices converge on value. -

15.535 Class #2 “Valuation Basics”

15.535 Class #2 “Valuation Basics” 15.535 - Class #2 1 Homepage Address http://mit.edu/wysockip/www Or (Click on “Analysts”) Check here for examples of projects from prior years. 15.535 - Class #2 2 Where Next? • Readings for Class #2 (Today) – Review your Finance notes on DCF – Skim Section B of Course Pack: “Free Cash Flow to Equity Discount Models” (from Chapter 14 of Investment Valuation by Damodaran) • Readings for Class #3 (Tuesday) – Cash Flow Analysis – Skim Section D of Course Pack: “Income versus Cashflow” • Reminder to form teams for project 15.535 - Class #2 3 Recap From Last Class • Market Efficiency • Financial Statement Information used for: – Valuation – Contracting • Today – lay the groundwork for valuation – Take “baby steps” – by end of class will have basic tools to do a full-blown valuation 15.535 - Class #2 4 Firm Value and Future Cash Flows • The value of a firm (or shares in that firm) must be related to the (net) cash flows returned to owners of the firm. – If this is not true, then we have an arbitrage opportunity (money-making machine) • Expected future cash flows versus actual future cash flows 15.535 - Class #2 5 What is the source of flows? • As a first step, one must understand how firm will generate cash flows in the future! – Strategy, Economics, Marketing, Operations, etc. • Must appreciate competitive market forces: – If a company has a great idea that will generate huge profits, competitors soon will follow! – Barriers to entry, first-mover advantage, monopoly • How will Compaq generate its future sales, profits, cash flows? 15.535 - Class #2 6 DCF is fundamental to everything we will do in this course • Must understand DCF analysis! – When we perform any type of valuation analysis … It will always boil down to DCF! • P/E multiples, PEG ratios, price targets – These all are transformations of DCF. -

Topic: FREE CASH FLOW to EQUITY (FCFE) MODEL WEEK4 LEVEL 2 EVA QUESTIONS

Topic: FREE CASH FLOW TO EQUITY (FCFE) MODEL WEEK4 LEVEL 2 EVA QUESTIONS 1. A manufacturing company is expected to have before-tax cash flow from operations of N750,000 in the coming year. The firm's corporate tax rate is 40%. It is expected that N250,000 of operating cash flow will be invested in new fixed assets. Depreciation for the year will be N125,000. After the coming year, cash flows are expected to grow at 7% per year. The appropriate market capitalization rate for unleveraged cash flow is 13% per year. The firm has no outstanding debt. What is the projected free cash flow of the company for the coming year? A. N250,000 B. N180,000 C. N300,000 D. N380,000 2. What is market value added (MVA)? It is: A. Net operating profit after taxes less capital charge. B. Free cash flow to the firm adjusted for abnormal earnings. C. Free cash flow to equity. D. It is the present value of all future economic value added (EVAs). 3. What is market value added (MVA)? It is: A. Net operating profit after taxes less capital charge. B. Free cash flow to the firm adjusted for abnormal earnings. C. Free cash flow to equity. D. It is the present value of all future economic value added (EVAs). 4.Cash flow return on investment (CFROI) differs from economic value added in that CFROI: A. Uses net cash flow rather than gross cash flow. B. Uses net investment rather than gross investment. C. Does not include non-depreciating assets. -

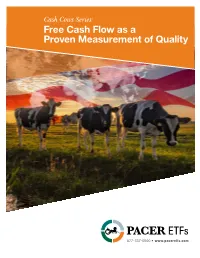

Free Cash Flow As a Proven Measurement of Quality

Free Cash Flow as a Proven Measurement of Quality Understanding the Terms A Source for Free Cash Flow Growing Wealth Free cash flow is the cash remaining after a company has paid: 1 The goal of most investors is to achieve financial security. High Free cash flow can be used to: free cash flow is an indicator of a company’s financial strength. 2 Positive free cash flow indicates Free Cash Flow Yield a company is generating more cash Free cash Free Cash Flow than it needs to run the business and flow yield = Enterprise Value can invest in growth opportunities. (FCFY) (Market Cap + Debt - Cash) 3 Free cash flow yield can determine an investor’s payback Companies generating high free period: Higher free cash flow yield = shorter payback period cash flow yields have the ability to FCFY 1% 2% 5% 10% grow dividends over time and produce Years to pay back all 100 50 20 10 debt and equity holders Years Years Years Years better earnings. “Equity Valuation: A Survey of Professional Practice.” 4 Using strategies that are 80 constantly re-evaluating and is the key to owning 70 66 rebalancing 63 15% of analysts surveyed 60 use free cash flow yield quality companies generating high 55 to evaluate investments. free cash flow. 50 40 37 P/E (Price to Earnings) ratio is share price divided by the 33 32 last twelve months earnings per share. (1)Includes multiples based on forecast operation income and Analysts Surveyed % Of 30 net income. (2) EBITDA - Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and 20 amortization.