The Ecclesiastical Coat of Arms Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COAT-OF-ARMS and FLAG Act 209 of 1911 an ACT to Adopt and Prescribe the Design of a State Coat-Of-Arms and State Flag, and Their

COAT-OF-ARMS AND FLAG Act 209 of 1911 AN ACT to adopt and prescribe the design of a state coat-of-arms and state flag, and their use; to prohibit the use of the same for advertising purposes; to prescribe standards for the manufacture, sale, and display of certain flags of the United States and the state flag; and to prescribe the powers and duties of certain state agencies and officials. History: 1911, Act 209, Eff. Aug. 1, 1911;Am. 2012, Act 167, Imd. Eff. June 14, 2012. The People of the State of Michigan enact: 2.21 State coat-of-arms; adoption. Sec. 1. The device and inscriptions of the great seal of the state of Michigan, Anno Domini 1835, presented by Lewis Cass to the forthcoming state, through the constitutional convention and adopted June 2, 1835, and filed with the secretary of the territory, June 24, 1835, and illustrated by a seal with said device and inscriptions attached to a state document, bearing date 1838, and to the constitution of 1850 received and filed in the office of the secretary of state, August 15, 1850, and now on file in said office, omitting the legend "The great seal of the state of Michigan, Anno Domini 1835," is hereby adopted as the coat-of-arms of the state. History: 1911, Act 209, Eff. Aug. 1, 1911;CL 1915, 1098;CL 1929, 134;CL 1948, 2.21. Compiler's note: For constitutional provision as to great seal of the state of Michigan referred to in this section, see now Const. -

MEDIEVAL ARMOR Over Time

The development of MEDIEVAL ARMOR over time WORCESTER ART MUSEUM ARMS & ARMOR PRESENTATION SLIDE 2 The Arms & Armor Collection Mr. Higgins, 1914.146 In 2014, the Worcester Art Museum acquired the John Woodman Higgins Collection of Arms and Armor, the second largest collection of its kind in the United States. John Woodman Higgins was a Worcester-born industrialist who owned Worcester Pressed Steel. He purchased objects for the collection between the 1920s and 1950s. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 3 Introduction to Armor 1994.300 This German engraving on paper from the 1500s shows the classic image of a knight fully dressed in a suit of armor. Literature from the Middle Ages (or “Medieval,” i.e., the 5th through 15th centuries) was full of stories featuring knights—like those of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, or the popular tale of Saint George who slayed a dragon to rescue a princess. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 4 Introduction to Armor However, knights of the early Middle Ages did not wear full suits of armor. Those suits, along with romantic ideas and images of knights, developed over time. The image on the left, painted in the mid 1300s, shows Saint George the dragon slayer wearing only some pieces of armor. The carving on the right, created around 1485, shows Saint George wearing a full suit of armor. 1927.19.4 2014.1 WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 5 Mail Armor 2014.842.2 The first type of armor worn to protect soldiers was mail armor, commonly known as chainmail. -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

British Royal Banners 1199–Present

British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Geoff Parsons & Michael Faul Abstract The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. It continues to show how King Edward III added the French Royal Arms, consequent to his claim to the French throne. There is then the change from “France Ancient” to “France Modern” by King Henry IV in 1405, which set the pattern of the arms and the standard for the next 198 years. The story then proceeds to show how, over the ensuing 234 years, there were no fewer than six versions of the standard until the adoption of the present pattern in 1837. The presentation includes pictures of all the designs, noting that, in the early stages, the arms appeared more often as a surcoat than a flag. There is also some anecdotal information regarding the various patterns. Anne (1702–1714) Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 799 British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Figure 1 Introduction The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. Although we often refer to these flags as Royal Standards, strictly speaking, they are not standard but heraldic banners which are based on the Coats of Arms of the British Monarchs. Figure 2 William I (1066–1087) The first use of the coats of arms would have been exactly that, worn as surcoats by medieval knights. -

If the Hat Fits, Wear It!

If the hat fits, wear it! By Canon Jim Foley Before I put pen to paper let me declare my interests. My grandfather, Michael Foley, was a silk hatter in one of the many small artisan businesses in Claythorn Street that were so characteristic of the Calton district of Glasgow in late Victorian times. Hence my genetic interest in hats of any kind, from top hats that kept you at a safe distance, to fascinators that would knock your eye out if you got too close. There are hats and hats. Beaver: more of a hat than an animal As students for the priesthood in Rome the wearing of a ‘beaver’ was an obligatory part of clerical dress. Later, as young priests we were required, by decree of the Glasgow Synod, to wear a hat when out and about our parishes. But then, so did most respectable citizens. A hat could alert you to the social standing of a citizen at a distance of a hundred yards. The earliest ‘top’ hats, known colloquially as ‘lum’ hats, signalled the approach of a doctor, a priest or an undertaker, often in that order. With the invention of the combustion engine and the tram, lum hats had to be shortened, unless the wearer could be persuaded to sit in the upper deck exposed to the elements with the risk of losing the hat all together. I understand that the process of shortening these hats by a few inches led to a brief revival of the style and of the Foley family fortunes, but not for long. -

Theosophical Symbology Some Hints Towards Interpretation of the Symbolism of the Seal of the Society

Theosophical Siftings Theosophical Symbology Vol 3, No 4 Theosophical Symbology Some Hints Towards Interpretation of the Symbolism of the Seal of the Society by G.R.S. Mead, F.T.S. Reprinted from “Theosophical Siftings” Volume 3 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England "A combination and a form, indeed, Where every god did seem to set his seal, To give the world assurance of a MAN." As the question is often asked, What is the meaning of the Seal of the Society, it may not be unprofitable to attempt a rough outline of some of the infinite interpretations that can be discovered therein. When, however, we consider that the whole of our philosophical literature is but a small contribution to the unriddling of this collective enigma of the sphinx of all sciences, religions and philosophies, it will be seen that no more than the barest outlines can be sketched in a short paper. In the first place, we are told that to every symbol, glyph and emblem there are seven keys, or rather, that the key may be turned seven times, corresponding to all the septenaries in nature and in man. We might even suppose, by using the law of analogy, that each of the seven keys might be turned seven times. So that if we were to suggest that these keys may be named the physiological, astronomical, cosmic, psychic, intellectual and spiritual, of which divine interpretation is the master-key, we should still be on our guard lest we may have confounded some of the turnings with the keys themselves. -

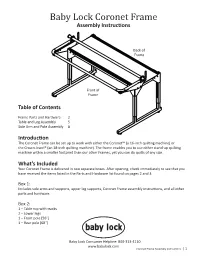

Coronet (BLCT16) Frame Assembly Instructions REVISED

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 REVISIONS ECO REV. DESCRIPTION DATE APPROVED A INITIAL RELEASE D D Baby Lock Coronet Frame Assembly Instructions Back of Frame C C Front of Frame Table of Contents Frame Parts and Hardware 2 BILL OF MATERIALS ENG-10007 Table and Leg Assembly 5 ITEM PART NUMBER DESCRIPTION QTY. Side Arm and Pole Assembly 8 1 QF05300-300 TABLE ASSY, TACONY FRAME 1 2 QF05300-402 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, A 2 B Introduction 3 QF05300-403 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, B 2 B The Coronet Frame can be set up to work with either the Coronet™ (a 16-inch quilting machine) or 4 QF05300-401 END LEG STAND 2 the Crown Jewel® (an 18-inch quilting machine). The frame enables you to use either stand-up quilting 5 QF09318-303 SCREW-M6x12 SWH 6 machine within a smaller footprint than our other Frames, yet you can do quilts of any size. 6 QF09318-07 Screw-M8x16 SBHCS 16 7 QF09318-108 LEVELING GLIDE 4 What’s Included 8 ENG-10005 ASSY-SIDE ARM RIGHT LF 1 Your Coronet Frame is delivered in two separate boxes. After opening, check immediately to see that you 9 ENG-10006 ASSY-SIDE ARM LEFT LF 1 have received the items listed in the Parts and Hardware list found on pages 2 and 3. 10 QF10005 POLE FRONT LF 1 11 QF10009 POLE REAR LF 1 Box 1: 12 QF10011 END CAP-REAR POLE LF 2 Includes side arms and supports, upper leg supports, Coronet Frame assembly instructions, and all other UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED: NAME DATE parts and hardware. -

Bishop Barron Blazon Texts

THE FORMAL BLAZON OF THE EPISCOPAL COAT OF ARMS OF ROBERT E. BARRON, S.T.D. D.D. K.H.S. TITULAR BISHOP OF MACRIANA IN MAURETANIA AUXILIARY TO THE METROPOLITAN OF LOS ANGELES PER PALE OR AND MURREY AN OPEN BOOK PROPER SURMOUNTED OF A CHI RHO OR AND ENFLAMED COUNTERCHANGED, ON A CHIEF WAVY AZURE A PAIR OF WINGS ELEVATED, DISPLAYED AND CONJOINED IN BASE OR CHARGED WITH A FLEUR-DE-LIS ARGENT AND FOR A MOTTO « NON NISI TE DOMINE » THE OFFICE OF AUXILIARY BISHOP The Office of Auxiliary, or Assistant, Bishop came into the Church around the sixth century. Before that time, only one bishop served within an ecclesial province as sole spiritual leader of that region. Those clerics who hold this dignity are properly entitled “Titular Bishops” whom the Holy See has simultaneously assigned to assist a local Ordinary in the exercise of his episcopal responsibilities. The term ‘Auxiliary’ refers to the supporting role that the titular bishop provides a residential bishop but in every way, auxiliaries embody the fullness of the episcopal dignity. Although the Church considers both Linus and Cletus to be the first auxiliary bishops, as Assistants to St. Peter in the See of Rome, the first mention of the actual term “auxiliary bishop” was made in a decree by Pope Leo X (1513‐1521) entitled de Cardinalibus Lateranses (sess. IX). In this decree, Leo confirms the need for clerics who enjoy the fullness of Holy Orders to assist the Cardinal‐Bishops of the Suburbicarian Sees of Ostia, Velletri‐Segni, Sabina‐Poggia‐ Mirteto, Albano, Palestrina, Porto‐Santo Rufina, and Frascati, all of which surround the Roman Diocese. -

The Coat of Arms of the MOST REVEREND KEVIN J

The Coat of Arms of THE MOST REVEREND KEVIN J. FARRELL, D.D. Bishop of Dallas BLAZON (heraldic description): Arms impaled. In the dexter: Gules, on a fess per bend wavy Argent three fleurs de lis Azure, in the sinister chief two crossed swords Argent, in the dexter base a molet Argent. In the sinister: Per fess Or and Azure, a lion rampant per fess Gules and Or, standing on a mound of rock Argent. SIGNIFICANCE: The dexter impalement (on the observer’s left) displays the arms of the Diocese of Dallas. The red field honors the Sacred Heart. The diagonal wavy band with three fleurs de lis represents the Trinity River, named by early Spanish explorers, which flows through the diocese. The fleur de lis appears on the coat of arms of Pope Leo XIII, who established the Diocese of Dallas in 1890. The two silver swords in the upper right honor St. Paul, patron of the first permanent Catholic settlement in northeast Texas. The sword was the instrument of St. Paul's martyrdom. The star in the lower left locates Dallas in Texas, the Lone Star State. The sinister impalement displays the arms of Bishop Farrell. The lion rampant honors Theodore Cardinal McCarrick, Archbishop emeritus of Washington, and the Irish sept of O'Farrell. In the upper portion of the shield, gold (yellow) and the lion (red) are derived from the Arms of Cardinal McCarrick, whom Bishop Farrell assisted as Auxiliary Bishop of Washington. The lower portion of the lion in gold (yellow) derives from the Irish sept of O'Farrell. -

The Armorial Windows of Woodhouse Chapel

nf Jtrailli. WITH REFERENCES TO THE ARMORIAL SHIELDS IN WOODHOUSE CHAPEL. (N. stands for the North Windows, S.for the South, and E.for the East.) Maude Percy .tpJohn lord Neville.=y=Elizabeth Latimer. TI ——1 Margaret Staf-=i pRalph first Earl of=i =Joane Beau-= f=Robert Ferrers of Oversley. Thomas lord Furnival. John lord Latimer. ford. Westmerland. fort. (1st husb.) (page 327.) (page 327.) (Note, p. 327.) John lord Ealph Margaret lady Richard William lord Fauconberg. (N. 7.) KATHARINE DUCHESS OF NORFOLK. El zabeth lady Neville. Neville Sorope. (N. 11.) Earl of George lord Latimer. (N. 6.) (N. 3 and S. 2.) Greystock (p. 327.) ofOvers-Philippa lady Salisbury Robert bishop of Durham. (N. 8.) Alianor Countess of Northumber- (N. 9), and =f= ley. Dacre. (N. 12.) (N. 5.) Edward lord Abergavenny. land. (N. 8.) Mary lady Ne- I (S.I.) =f (p. 330.) Anne Duchess of Buckingham. (N.4.) villeofOvers- I ( Cecily Duchess of York. (p. 337.) ley. (p. 333.) ! 1 King Heniy= =Margaret Ralph 2d Earl of Sir John Sir Thomas ]EUchard Earl of Warwick Katharine= =Wiffiam lord Has VI. (E. 3.) of Anjon. Westmerland. Neville. Neville, and Salisbury. Neville. tings, (p. 339.) (E.4.) (N. 1.) (N. 10.) (p. 330.) I Edward Prince of Wales.=Anne Neville. Hastings Earl of Huntingdon. (Anns in the East Window.) THE ARMQRIAL WINDOWS OF WOODHOUSE CHAPEL. 317 MR. JOHN GOUGH NICHOLS, F.S.A., read a Paper on THE ARMORIAL WINDOWS erected in the reign of Henry VI. by John Viscount Beaumont and Katharine Duchess of Norfolk in WOODHOUSE CHAPEL, by the Park of Beaumanor, in Charnwood Forest, Leicestershire. -

North Carrick Newsletter Summer 2021

Summer issue 2021 www.nccbc.org FREE With Summer upon us and lockdown easing, we are all looking forward to a better year Published by Produced with funding provided from ScottishPower Renewables View ALL newsletters online The ‘Newsletters’ section is where there will be copies of all of the North Carrick Community Newsletters (past and present). This will be useful for people who like to read things on screen or who want to send electronic copies to friends. www.nccbc.org.uk North Carrick Community Benefit Your voice matters... Company We would like all communities in North Carrick and individuals to get involved with the Funding is available for a wide production of this publication. This is YOUR range of projects and to find out newsletter, so please use it to your benefit. more or to apply to this fund please contact Marion Young on 01292 612626 or your The North Carrick Community Newsletter is produced with community council representatives. You funding provided from ScottishPower Renewables can also contact the company directly on [email protected] We want to encourage everyone to contribute. We also welcome your comments and thoughts on the newsletter as well as any Copies of the newsletter are delivered to ideas on what you would like to see more of (or less). This is every house in Maybole and the North our thirteenth issue and we want to ensure the newsletter Carrick villages. If, for any reason,you grows from strength to strength but we cannot achieve this don’t receive a copy please let your without the participation of our readers and advertisers.