Theory and Practice in the Works of Pietro Pontio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Motets of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli in the Rokycany Music Collection

Musica Iagellonica 2017 ISSN 1233–9679 Kateřina Maýrová (Czech Museum of Music, Prague) The motets of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli in the Rokycany Music Collection This work provides a global survey on the Italian music repertoire contained in the music collection that is preserved in the Roman-Catholic parish of Roky- cany, a town located near Pilsen in West-Bohemia, with a special regard to the polychoral repertoire of the composers Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli and their influence on Bohemian cori-spezzati compositions. The mutual comparison of the Italian and Bohemian polychoral repertoire comprises also a basic compara- tion with the most important music collections preserved in the area of the so- called historical Hungarian Lands (today’s Slovakia), e.g. the Bardejov [Bart- feld / Bártfa] (BMC) and the Levoča [Leutschau / Löcse] Music Collections. From a music-historical point of view, the Rokycany Music Collection (RMC) of musical prints and manuscripts stemming from the second half of the 16th to the first third of the 17th centuries represents a very interesting complex of music sources. They were originally the property of the Rokycany litterati brotherhood. The history of the origin and activities of the Rokycany litterati brother- hood can be followed only in a very fragmentary way. 1 1 Cf. Jiří Sehnal, “Cantionál. 1. The Czech kancionál”, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie, 29 vols. (London–New York: Macmillan, 20012), vol. 5: 59–62. To the problems of the litterati brotherhoods was devoted the conference, held in 2004 65 Kateřina Maýrová The devastation of many historical sites during the Thirty Years War, fol- lowed by fires in 1728 and 1784 that destroyed much of Rokycany and the church, resulted in the loss of a significant part of the archives. -

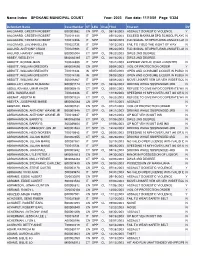

2003 Name Index

Name Index SPOKANE MUNICIPAL COURT Year: 2003 Run date: 11/10/09 Page 1/324 Defendant Name Case Number CT LEA Disp Filed Charge1 DV AALGAARD, CRESTIN ROBERT B00003582 CN SPP CL 08/18/2003 ASSAULT DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Y AALGAARD, CRESTIN ROBERT T00011933 IT SPP 05/13/2003 EXCEED MAXIMUM SPD SCHOOL/PLAYG NCRO AALGAARD, CRESTIN ROBERT T00014306 IT SPP 06/02/2003 FLD SIGNAL STOPS/TURNS-UNSAFE LANEN AALGAARD, JAILYNN ELLEN T00023736 IT SPP 10/13/2003 FAIL TO YIELD THE RIGHT OF WAY N AALUND, ANTHONY CRAIG T00020908 IT SPP 09/22/2003 FLD SIGNAL STOPS/TURNS-UNSAFE LANEN AALUND, HARVEY JAMES B00005004 CT SPP CL 09/22/2003 DWLS 2ND DEGREE ABBEY, WESLEY H M00062365 CT SPP CL 06/16/2003 DWLS 2ND DEGREE ABBOTT, BONNIE JEAN T00024880 IT SPP 10/21/2003 EXPIRED VEH LIC OVER 2 MONTHS N ABBOTT, WILLIAM GREGORY M00058696 CN SPP 05/08/2003 VIOL OF PROTECTION ORDER Y ABBOTT, WILLIAM GREGORY T00011634 IN SPP 05/07/2003 OPEN AND CONSUME LIQUOR IN PUBLICN ABBOTT, WILLIAM GREGORY T00014198 IN SPP 09/03/2003 OPEN AND CONSUME LIQUOR IN PUBLICN ABBOTT, WILLIAM JAY S00016867 IT SPP 04/08/2003 MOVE UNSAFE VEH OR VEH W/DEF EQUIPN ABDULLAH, ASSAD MUBARAK B00001174 CT SPP CL 08/26/2003 DRIVING WHILE SUSPENDED 3RD N ABDUL RAHIIM, UMAR KHIDR B00000815 CT SPP CL 05/01/2003 REFUSE TO GIVE INFO/COOPERATE W/OFFN ABEL, SANDRA SUE T00026936 IT SPP 11/19/2003 SPEEDING 10 MPH OVER LIMIT (40 OR U N ABENAT, ABERTA M B00001328 CT SPP CL 06/23/2003 REFUSE TO GIVE INFO/COOPERATE W/OFFN ABEYTA, JOSEPHINE MARIE M00060068 CN SPP 01/15/2003 ASSAULT N ABGHARI, REZA A00000181 CN SPP CL 01/27/2003 -

Paper for Tivoli

Edinburgh Research Explorer Giovanni Maria Nanino and the Roman confraternities of his time Citation for published version: O'Regan, N 2008, Giovanni Maria Nanino and the Roman confraternities of his time. in G Monari & F Vizzacarro (eds), Atti e memorie della Società Tibertina di storia e d’arte: Atti della Giornata internazionale di studio, Tivoli, 26 October 2007. vol. 31, Tivoli, pp. 113-127. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Atti e memorie della Società Tibertina di storia e d’arte Publisher Rights Statement: © O'Regan, N. (2008). Giovanni Maria Nanino and the Roman confraternities of his time. In G. Monari, & F. Vizzacarro (Eds.), Atti e memorie della Società Tibertina di storia e d’arte: Atti della Giornata internazionale di studio, Tivoli, 26 October 2007. (Vol. 31, pp. 113-127). Tivoli. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 GIOVANNI MARIA NANINO AND THE ROMAN CONFRATERNITIES OF HIS TIME NOEL O’REGAN, The University of Edinburgh Giovanni Maria Nanino was employed successively by three of Rome’s major institutions: S. -

Lucrezia Vizzana's Componimenti

“READING BETWEEN THE BRIDES”: LUCREZIA VIZZANA’S COMPONIMENTI MUSICALI IN TEXTUAL AND MUSICAL CONTEXT BY Copyright 2011 KATRINA MITCHELL Submitted to the graduate degree program in the School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Paul Laird _________________________________ Dr. Charles Freeman _________________________________ Dr. Thomas Heilke _________________________________ Dr. Deron McGee _________________________________ Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz Date Defended: 9 June 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Katrina Mitchell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “READING BETWEEN THE BRIDES”: LUCREZIA VIZZANA’S COMPONIMENTI MUSICALI IN TEXTUAL AND MUSICAL CONTEXT _________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Paul Laird Date approved: 9 June 2011 ii ABSTRACT “Reading Between the Brides”: Lucrezia Vizzana’s Componimenti musicali in Textual and Musical Context There had never been a Bolognese nun known to have published her music when Lucrezia Vizzana’s Componimenti musicali was printed in 1623, nor has there been any since then. This set of twenty motets became a window into the musical world of cloistered nuns in the seventeenth century. Following the research of Craig Monson in Disembodied Voices: Music and Culture in an Early Modern Italian Convent (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), this project identifies similarities and differences present in Vizzana’s motets using a number of clarifying means not yet explored. Looking at each work in detail, we are able to surmise some favorite musical devices of Vizzana and how they fit in with other monodists of the day. This project fills a specific lacuna in that ten of the twenty motets are not known to be published in modern notation and are available here for the first time in that form. -

The Organ Ricercars of Hans Leo Hassler and Christian Erbach

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame 3. When a map, dravdng or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

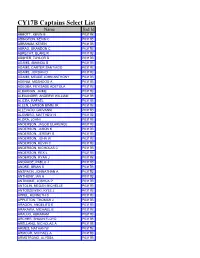

CY17B Captains Select List

CY17B Captains Select List Name Brd Id ABBOTT, KEVIN B P0317B ABINGTON, KEVIN C P0317B ABRAHAM, KEVEN P0317B ABRAO, BRANDON C P0317B ABRECHT, BLAKE R P0317B ABSHER, TAYLOR B P0317B ADAMS, AMANDA S P0317B ADAMS, CARTER SANTIAGO P0317B ADAMS, JORDAN D P0317B ADAMS, MEADE JOHN ANTHONY P0317B ADENIJI, MOSHOOD A P0317B ADEOBA, FEYISADE ADETOLA P0317B ALBARRAN, JAIME P0317B ALEXANDER, ANDREW WILLIAM P0317B ALICEA, RAFAEL P0317B ALLEN, LAWSON BIMM JR P0317B ALLEVATO, GIOVANNI P0317B ALOMBRO, MATTHEW N P0317B ALORA, JOHN I P0317B ANDERSON, JACOB CLARENCE P0317B ANDERSON, JASON K P0317B ANDERSON, JEREMY B P0317B ANDERSON, JOHN W P0317B ANDERSON, KEVIN C P0317B ANDERSON, NICHOLAS C P0317B ANDERSON, REX L P0317B ANDERSON, RYAN J P0317B ANDRADE, PABLO J P0317B ANDRE, BRIAN S P0317B ANSPACH, JOHNATHAN A P0317B ANTHONY, IAN A P0317B ANTINONE, JOSHUA P P0317B ANTOLIN, MEGAN MICHELLE P0317B ANTOSZEWSKI, KYLE J P0317B APPEL, KENNETH S P0317B APPLETON, THOMAS J P0317B ARAGON, ANGELITO E P0317B ARAKAWA, MICHAEL B P0317B ARAUJO, ABRAHAM P0317B ARCHER, SHAUN FLOYD P0317B ARELLANO, NICHOLAS A P0317B ARMES, NATHAN W P0317B ARMOUR, MICHAEL A P0317B ARMSTRONG, ALYSSA P0317B ARMSTRONG, CHARLES J P0317B ARNOLD, TYLER S P0317B ARRINGTON, KRISTIAN C P0317B ARROWOOD, RYAN M P0317B ARTHUR, ROBERT L P0317B ARTMAN, MEGAN NICOLE P0317B ASHBY, ROBERT W P0317B ASHLEY, DAMIEN M P0317B ASSIMOS, CAITLIN E P0317B ASTUDILLO, JESSICA M P0317B ATTILLO, NICHOLAS H P0317B AUDETTE, MARK L P0317B AUSTIN, CHRISTINE M P0317B AYALA, CASSANDRA P0317B AYALA, STEVEN CHRISTOPHE P0317B AYCOX, -

Róża Różańska

Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ No. 32 (4/2017), pp. 59–78 DOI 10.4467/23537094KMMUJ.17.010.7839 www.ejournals.eu/kmmuj Róża Różańska JAGIELLONIAN UNIVERSITY IN KRAKÓW Leone Leoni as a Forgotten Composer of the Early Baroque Era Abstract The article is a pioneer attempt in Polish literature to develop a syn- thetic resume and the characteristics of the work of the Italian Baroque composer Leone Leoni. Leoni was highly valued in his time; also, he is said to be one of the creators of dramma per musica genre, and his religious compositions served as model examples of counterpoint for many centuries. The first part of the text presents the state of research concerning the life and work of the artist; then, the second part con- tains his biography. The last part discusses Leoni’s works. Finally, the rank of his output is regarded. Keywords Leone Leoni, small-scale concerto, madrigal, early Baroque The following article is a pioneer attempt in Polish literature to develop a synthetic resume of life and art of Leone Leoni (ca. 1560–1627), an Italian composer. Today forgotten, he was a highly valued artist in his epoch. He is regarded as one of the pioneers of dramma per musica and, 59 Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ, No. 32 (1/2017) through the centuries, his church music was used by music theorists as models of music rhetoric and concertato style in the compositions for small ensemble. The paper has been planned as an introduction to the cycle of arti- cles dedicated to Leone Leoni, and because of that it is general in the character. -

Exploring Implications of the Double Attribution of the Madrigal “Canzon Se L’Esser Meco” to Andrea Gabrieli and Orlande De Lassus

A 16th Century Publication Who-Dun-it: Exploring implications of the double attribution of the madrigal “Canzon se l’esser meco” to Andrea Gabrieli and Orlande de Lassus. Karen Linnstaedter Strange, MM A Double Attribution Why was a single setting of “Canzon se l’esser meco” published in 1584 and 1589 under different composers’ names? For centuries, music history has ascribed this setting of a text from a Petrarchan madrigale to either Orlande de Lassus or Andrea Gabrieli, depending on the publication. It has been assumed the two original publications contain distinct creations of “Canzon se l’esser meco,” and to support this confusion, slight differences in notation between the two modern editions induce an initial perception that the two pieces differ. (See Figures 1A & 1B.). With a few moments of comparison, one can see that the madrigal published under Orlande de Lassus’ name in 1584 is the same piece attributed to Andrea Gabrieli by a different publisher five years later. In fact, no difference exists in the original publications beyond incidental choices by the two publishers, such as the number of notes printed per line and the notation for repeated accidentals. 1 (See Figures 2-5 A & B.) Suppositions and Presumptions The exactness of the two publications provokes interesting questions about issues of personal composer relations and influence, study by copying, and misattribution. In exploring all the possibilities, some quite viable, others farfetched, we can perhaps gain a clearer overview of the issues involved. On the less viable side, perhaps the piece was written simultaneously by each composer and, through some miracle, the two pieces turned out to be exactly the same. -

Centenary Celebration Report

Celebrating 100 years CHOIR SCHOOLS’ ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE 2018 Front cover photograph: Choristers representing CSA’s three founding member schools, with lay clerks and girl choristers from Salisbury Cathedral, join together to celebrate a Centenary Evensong in St Paul’s Cathedral 2018 CONFERENCE REPORT ........................................................................ s the Choir Schools’ Association (CSA) prepares to enter its second century, A it would be difficult to imagine a better location for its annual conference than New Change, London EC4, where most of this year’s sessions took place in the light-filled 21st-century surroundings of the K&L Gates law firm’s new conference rooms, with their stunning views of St Paul’s Cathedral and its Choir School over the road. One hundred years ago, the then headmaster of St Paul’s Cathedral Choir School, Reverend R H Couchman, joined his colleagues from King’s College School, Cambridge and Westminster Abbey Choir School to consider the sustainability of choir schools in the light of rigorous inspections of independent schools and regulations governing the employment of children being introduced under the terms of the Fisher Education Act. Although cathedral choristers were quickly exempted from the new employment legislation, the meeting led to the formation of the CSA, and Couchman was its honorary secretary until his retirement in 1937. He, more than anyone, ensured that it developed strongly, wrote Alan Mould, former headmaster of St John’s College School, Cambridge, in The English -

Among the Not So Great / First Edition.– Pondicherry

AMONG THE NOT SO GREAT Among the Not So Great PRABHAKAR (Batti) NEW HOUSE KOLKATA First edition Sri Mira Trust 2003 Second enlarged edition New House 2018 Rs 270.00 © Sri Mira Trust 2003 Published by New House, Kolkata - 700 025 Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry Printed in India INTRODUCTION I write this about some old Ashramites — interesting people, who I feel should not be lost, buried in the past. I write of them for they are, or were, so garbed in their ordinariness that their coming, going and even their short sojourn here went unheralded, unnoticed and unsung. Maybe I use words too high-sounding, but I would that you let that pass. They did not achieve anything great (in the usual sense of the word) — for no poetry, prose or philosophy spewed forth from their innards. They created no piece of art nor did they even put up a block of masonry. But they achieved this — when you by chance thought of them a bubble of joy rose from your stomach, tingled its way up like a soda-induced burp. What more can one ask of another but this moment of joy? This is reason enough for me to bring them back from the past. These that I mention here were quite closely associated with me, and I think it would interest many who have not had the good chance to rub shoulders with them, nor even see them, probably. This is a homely “Who-is-who”. I first started writing this series with no idea whatsoever as to what I was going to do, once I had written. -

From Your Belly Flow Song-Flowers: Mexica Voicings in Colonial New Spain (Toward a Culturally-Informed Voice Theory and Practice)

FROM YOUR BELLY FLOW SONG-FLOWERS: MEXICA VOICINGS IN COLONIAL NEW SPAIN (TOWARD A CULTURALLY-INFORMED VOICE THEORY AND PRACTICE) by BETHANY MARIE BATTAFARANO A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts March 2021 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Bethany Marie Battafarano Title: From Your Belly Flow Song-flowers: Mexica Voicings in Colonial New Spain (Toward a Culturally-informed Voice Theory and Practice) This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Musicology by: Ed Wolf Chair Lori Kruckenberg Member Drew Nobile Member And Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2021. ii © 2021 Bethany Marie Battafarano This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Bethany Marie Battafarano Master of Arts School of Music and Dance March 2021 Title: From Your Belly Flow Song-flowers: Mexica Voicings in Colonial New Spain (Toward a Culturally-informed Voice Theory and Practice) In colonial New Spain, Indigenous peoples sang, played, and composed in western European musical styles, and Spanish composers incorporated Indigenous instruments, rhythms, and languages into their compositions. However, modern vocalists in the United States often overlook or misrepresent Indigenous features in performances of New Spanish repertoire. Vocalists typically must make choices about vocal techniques alone and, largely for lack of resources, in uninformed ways. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’