IN LEWIS and Requirements for Graduation With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buffalo Bill Memorial Association, Preserving Collections at The

DIVISION OF PRESERVATION AND ACCESS Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/divisions/preservation for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Preserving Collections at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West Institution: Buffalo Bill Memorial Association Project Director: Beverly Nadeen Perkins Grant Program: Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections Buffalo Bill Center of the West Narrative Introduction The Buffalo Bill Center of the West (Center) requests $48,933 from the National Endowment for the Humanities Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections to develop a comprehensive plan to solve collections preservation issues in the Center’s existing storage and work areas. The planning grant will support a team of consultants who will work with Center curators, the conservator, and museum services staff to evaluate vault space as well as workstations that serve staff, collections activities, professional researchers, and the public. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

RICHARD BRUNING • BATTON LASH • BILL MORRISON • GABRIEL HARDMAN & CORINNA BECHKO Winter 2015 • Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 7 Table of Contents

Illustration ©2015 Bernie Wrightson plus: 0 1 A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows RICHARD BRUNING LASH •BILL MORRISON •BATTON •GABRIEL HARDMAN & CORINNA BECHKO 1 82658 97073 4 No. 7,Winter2015 in theUSA $ 8.95 Winter 2015 • Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Ye Ed’s Rant: Weight Lifts, Spirit High ............................................................................ 2 ZOMBIE WOODY COMICS CHATTER CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2015 J.D. King. Gabriel Hardman & Corinna Bechko: The creative team (and married couple) About Our talk about their collaborations and individual achievements in comics ........................... 3 Cover Art by B ERNIE Incoming: Russ Heath, Denis Kitchen, and Batgirl’s Boots ............................................. 6 WRIGHTSON The Good Stuff: George Khoury on Designer Richard Bruning ..................................... 10 Color by TOM ZIUKO Twenty Years of Terror!: Bill Morrison on two decades of Treehouse of Horror ........ 14 Hembeck’s Dateline: Fred’s brief shining moment of abject terror ............................. 23 The Batton Lash Story: Part one of our interview with Supernatural Law’s creator ... 24 THE SUBLIME ART OF HORROR The Bernie Wrightson Interview: An exhaustive discussion with one of the finest artists in the history of comic books and book illustration ...........36 Art ©2015 Bernie Wrightson. Creator’s Creators: Richard J. Arndt ............................................................................. 79 In 1974, BERNIE WRIGHTSON drew a number of monster images -

ABC.V2.Catalog.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Art . 1 Urban Art . 13 Classic & Contemporary Illustration . 19 Graphic Novels & Comics . 29 Photography . 35 Film. 41 Not Just For Children . 47 Design & Fashion . 51 Cover Image: “Keep Left” – Banksy, from Banksy’s Bristol, courtesy of Last Gasp, page 3 of this catalog Cover & Catalog Design by Rama Crouch-Wong Catalog Layout by Dan Nolte Art ART I NEW ROME-ANTIC DELUSIONS Art By Jeremy Fish Drago invited Jeremy Fish to come to Rome and create site-specific works, a remix of Jeremy’s images, with an Italian touch added to his usual cast of characters and rich iconography. Fish’s symbiotic work with the Eternal City uses a library of symbols and characters to tell real-life narratives in a surreal way and alter the established order. His vivid imagination stems from his bilateral artistic persona, which combines solitary introspection with the exuberance of changing perspectives. $29.00 8x12in 978-88-88493-31-2 Available ISBN paperback 96pgs Drago SCB ART BOOK CATALOG | 1 I ART MUERTE NEW Art By Mike Giant Muerte is a celebration of the master of black ink, Mike Giant. Whether his medium is concrete, paper or skin, his signature style – made up of equal parts Mexican folk art and Japanese illustration – is unmis- takable and interna- tionally imitated. $29.00 8x10in 978-88-88493-19-0 Available ISBN paperback 96pgs Drago NEW NEW CITY SLANG:THE STREET NATION OF ANGELA COMES TO THE GALLERY By Sophie Toulouse Foreword By Micol Di Veroli A multimedia project about a communal utopia centered A richly-illustrated bilingual (Italian and English) on glamor and luxury. -

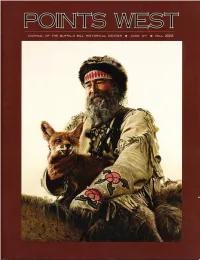

Points-West 2003.09.Pdf

I t Contents 2 Working with Camera, Canvas, and Brush: The Cody Art Colory by Julie Coleman Curatorial Assistant, Whitney Gallery of Western Art 9 James Bama: Choosing Cody,Attaining Art by Sarah E. Boehme, Ph.D. The John S. Bugas Curator, Whitney Gallery of Western Art l5 Alchemists of Cody by Warren Newman Curatorial Assistant, Cody Firearms Museum 22 Twenty-two Years of the Buffalo Bill Art Show &- Sale by Mark Bagne 27 The History of the Western Design Conference by Laurie R. Quade 3l Happy Trails: BufJalo BiIl Historical Center Hosts Members' Trail Ride by Kathy Mclane Director of Membership Cover: o 2003 Buffalo Bill Historicaj Center Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials jn any medium or James Bama (b. 1926), Timber format. All photographs in Points West are Buflalo Bill Historical Center JackJoe and His Fox, 1 979. Oil on photos unless otherwise noted. Address correspondence to Editor, Points west, Buflalo Bill Historjcal Center, 720 Sheridan Avenue. Cody, artist's board. 30 x 23.875 inches. Wyoming 82414 ot [email protected]. Bulfalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming. Gift in honor Edilor: Thom Huge and Designer: Jan Woods-Krier/PRODESIGN of Peg Coe, with respect Production Coordinator Kimber Swenson admrration, from Dick and Helen PhotoqraphV Staff: Chris Gimmeson Cashman, 1 9.98.1 .oJames E. Bama. Sean Campbell Sarah Cimmeson, lntern, page 16 A number of Bama's paintjngs Points West is published quarterly as a benefit of membership in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. For membership information contact: portray contemporary individuals Kathy Mclane, Director of Membership who choose to jdentily with the Buffalo Bill Historical Center historic past. -

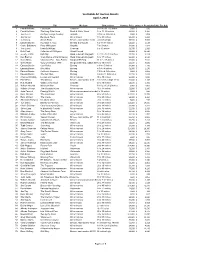

2018 Results.Xlsx

Scottsdale Art Auction Results April 7, 2018 Lot Artist Title Medium Dimensions Hammer PriceHammer + PremiumAvailable For Sale 1 Frank Hoffman Columbine Gouache 14 3/4 x 11 1/2 inches $800 $ 936 2 Frank Hoffman The Long Ride Home Black & White Wash 18 x 13 1/2 inches $1,800 $ 2,106 3 Joe Beeler An Open Range Cowboy Graphite 9 1/4 x 5 3/4 inches $900 $ 1,053 4 Jim Norton Buckley's Place Oil on board 18 x 24 inches $1,200 $ 1,404 5 G. Harvey Green Broke Bronze, cast number 20/30 24 inches high $6,500 $ 7,605 6 Edward Borein Noontime in Taos Etching & Dry point 8 x 11 3/4 inches $1,400 $ 1,638 7 Carrie Ballantyne Perry Whiteplum Graphite 7 x 6 inches $1,300 $ 1,521 8 Tom Lovell Friendly Willows Charcoal 6 x 10 inches $1,700 $ 1,989 9 Dale Ford Collection of 5 Wagons Wood Carved $9,000 $ 10,530 10 George Catlin Ball Play Hand Colored Lithograph 12 1/2 x 18 1/2 inches $2,750 $ 3,218 11 Karl Bodmer Scalp Dance of the Minitarres Hand Colored Lithograph 12 x 17 inches $3,000 $ 3,510 12 Gene Kloss Christmas Eve - Taos Pueblo Dry point Etching 11 1/2 x 15 inches $3,000 $ 3,510 13 Gene Kloss Song of Creation 1949 Dry point Etching, edition 59/7512 x 15 inches $3,500 $ 4,095 14 Edward Borein Cow Pokes Etching 6 3/4 x 5 inches $1,000 $ 1,170 15 Edward Borein Who Wins Etching 4 3/4 x 4 inches $1,000 $ 1,170 16 Edward Borein California Vaqueros Etching 7 3/4 x 6 3/4 inches $900 $ 1,053 17 Edward Borein The Bell Mare Etching 9 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches $2,250 $ 2,633 18 Charles Schridde Locked and Loaded Oil on canvas 40 x 30 inches $6,000 $ 7,020 19 Fritz White The Winners Bronze, cast number 6/25 9 1/2 inches high, 17 inches wide $1,800 $ 2,106 20 R.S. -

Entertainment Memorabilia, 3 July 2013, Knightsbridge, London

Bonhams Montpelier Street Knightsbridge London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax 20771 Entertainment Memorabilia, Entertainment 3 July 2013, 2013, 3 July Knightsbridge, London Knightsbridge, Entertainment Memorabilia Wednesday 3 July 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London International Auctioneers and Valuers – bonhams.com © 1967 Danjaq, LLC. and United Artists Corporation. All Rights reserved courtesy of Rex Features. Entertainment Memorabilia Wednesday 3 July 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services The following symbol is used Montpelier Street Director Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm to denote that VAT is due on the hammer price and buyer’s Knightsbridge Stephanie Connell +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 premium London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see back of catalogue † VAT 20% on hammer price for important notice to bidders and buyer’s premium Viewing Senior Specialist Sunday 30 June Katherine Williams Illustrations * VAT on imported items at 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7393 3871 Front cover: Lot 236 a preferential rate of 5% on Monday 1 July [email protected] Back cover: Lot 109 hammer price and the prevailing 9am to 4.30pm Inside front cover: Lot 97 rate on buyer’s premium Consultant Specialist Inside back cover: Lot 179 Tuesday 2 July W These lots will be removed to Stephen Maycock 9am to 4.30pm Bonhams Park Royal Warehouse Wednesday 3 July +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 after the sale. Please read the 9am to 11am [email protected] sale information page for more details. -

Adapting the Graphic Novel Format for Undergraduate Level Textbooks

ADAPTING THE GRAPHIC NOVEL FORMAT FOR UNDERGRADUATE LEVEL TEXTBOOKS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian M. Kane, M.A. Graduate Program in Arts Administration, Education, and Policy The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Candace Stout, Advisor Professor Clayton Funk Professor Shari Savage Professor Arthur Efland Copyright by Brian M. Kane 2013 i ABSTRACT This dissertation explores ways in which the graphic narrative (graphic novel) format for storytelling, known as sequential art, can be adapted for undergraduate-level introductory textbooks across disciplines. Currently, very few graphic textbooks exist, and many of them lack the academic rigor needed to give them credibility. My goal in this dissertation is to examine critically both the strengths and weaknesses of this art form and formulate a set of standards and procedures necessary for developing new graphic textbooks that are scholastically viable for use in college-level instruction across disciplines. To the ends of establishing these standards, I have developed a four-pronged information-gathering approach. First I read as much pre factum qualitative and quantitative data from books, articles, and Internet sources as possible in order to establish my base of inquiry. Second, I created a twelve-part dissertation blog (graphictextbooks.blogspot.com) where I was able to post my findings and establish my integrity for my research among potential interviewees. Third, I interviewed 16 professional graphic novel/graphic textbook publishers, editors, writers, artists, and scholars as well as college professors and librarians. Finally, I sent out an online survey consisting of a sample chapter of an existing graphic textbook to college professors and asked if the content of the source material was potentially effective for their own instruction in undergraduate teaching. -

Barks's Personal Reference Library

AFTERCarl Barks painting fine-art cartoons in oils by Copyright 2010 by John Garvin www.johngarvin.com Published by Enchanted Images Inc. www.enchantedimages.com All illustrations in this book are copyrighted by their respective copy- right holders (according to the original copyright or publication date as printed in/on the original work) and are reproduced for historical reference and research purposes. Any omission or incorrect informa- tion should be transmitted to the publisher so it can be rectified in future editions of this book. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9785946-4-0 First “Hunger Print” Edition November 2010 Edition size: 250 Printed in the United States of America about the “hunger” print “Hunger” (01-2010), 16” x 20” oil on masonite. “Hunger” was painted in early 2010 as a tribute to the painting genre pioneered by Carl Barks and to his techniques and craft. Throughout this book, I attempt to show how creative decisions – like those Barks himself might have made – helped shape and evolve the painting as I transformed a blank sheet of masonite into a fine-art cartoon painting. Each copy of After Carl Barks: Painting Fine-Art Cartoons in Oils includes a signed print of the final painting. 5 acknowledgements I am indebted to the following, in paintings and for being an important husband’s work. As the owner of alphabetical order: part of my life. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing. -

New Pulp-Related Books and Periodicals Available from Michael Chomko for October 2007

New pulp-related books and periodicals available from Michael Chomko for October 2007 As mentioned in my September list, I shipped a ton of books during the second week of September. Almost every regular customer received something or other from me. Our house is now quiet, with both kids off at college. My wife and I will be away from home beginning 10/4, celebrating our 29 th anniversary. We’ll be vacationing in Nova Scotia until 10/14. So if you write during that time, you won’t receive your answer until after the middle of the month. There are several pulp-related book shows coming up in the next few months. Gary Lovisi’s 19th Annual NYC Collectable Paperback & Pulp Fiction Expo will be held on Sunday October 7, 2007 at the Holiday Inn, 440 West 57th Street, New York City. For further information, please visit the Gryphon Book’s website at http://www.gryphonbooks.com/ . On Saturday and Sunday, October 20-21, in LaPlata, MO, the second annual DocCon will take place. Held in the hometown of Lester Dent, the creator of Doc Savage, the convention will feature a tour of the author’s home, a sneak preview of the Lester Dent Museum of Pulp History, special guests Anthony Tollin, current publisher of Doc and The Shadow, and Dr. Peter Koogan, a Wold Newton expert, and more. There are no membership fees, dealer fees, or anything of that nature. For further information, please visit the convention website at http://www.freewebs.com/doccon2/index.htm . On Saturday, November 3, 2007, Rich Harvey’s seventh annual Pulp Adventurecon will be held at the Ramada Inn, 1083 Rte 206 North, Bordentown, NJ. -

The Rage for Cowboy Art

The Rage for Cowboy Art In the Western states, prices are soaring for contemporary paintings that dφict cowboy and Indian themes. The best Western artists are now ready to storm the ramparts of the Eastern Establishment. BY JOSHUA GILDER ou can tell a successful cowboy the bend in your knee." medium-sized oil by Clark Heulings artist by the boots that line the floor Not, as you might think, to keep out went for a record $310,000, the most ever Yof his closet: snakeskin, elephant scorpions. This is purely a question of paid at auction for the work of a living ear, lizard, eel, and the aristocrat of cow fashion. These are "party" boots, for artist. Some grumbling was heard that boy boots, ostrich, the ones all covered wearing to occasions like the annual Jim Fowler, the Phoenix art dealer who with little black bumps where they pulled Western Heritage Sale, an auction of made the winning bid, already owned out the feathers. Gary Niblett, at 38 the Western art held every spring in the lobby some 20 Heulings and was trying to youngest member of the prestigious of the Shamrock Hilton in downtown inflate the value of his stock. ABC's Cowboy Artists of America, has his Houston. Attended by big oil money, big 20/20 was there to interview him, and boots custom-made. He pulls up his jeans cattle money, and prominent politicians one Santa Fe dealer remarked that if leg to reveal a shiny black expanse of (John Connally, a long-time enthusiast Fowler had known that he was going to sharkskin running up the length of his of Western art, is a sponsor), the sale is be on TV, he would have bid a million.