Musicolinguistic Artistry of Niraval in Carnatic Vocal Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Rakti in Raga and Laya

VEDAVALLI SPEAKS Sangita Kalanidhi R. Vedavalli is not only one of the most accomplished of our vocalists, she is also among the foremost thinkers of Carnatic music today with a mind as insightful and uncluttered as her music. Sruti is delighted to share her thoughts on a variety of topics with its readers. Rakti in raga and laya Rakti in raga and laya’ is a swara-oriented as against gamaka- complex theme which covers a oriented raga-s. There is a section variety of aspects. Attempts have of exponents which fears that ‘been made to interpret rakti in the tradition of gamaka-oriented different ways. The origin of the singing is giving way to swara- word ‘rakti’ is hard to trace, but the oriented renditions. term is used commonly to denote a manner of singing that is of a Yo asau Dhwaniviseshastu highly appreciated quality. It swaravamavibhooshitaha carries with it a sense of intense ranjako janachittaanaam involvement or engagement. Rakti Sankarabharanam or Bhairavi? rasa raga udaahritaha is derived from the root word Tyagaraja did not compose these ‘ranj’ – ranjayati iti ragaha, ranjayati kriti-s as a cluster under the There is a reference to ‘dhwani- iti raktihi. That which is pleasing, category of ghana raga-s. Older visesha’ in this sloka from Brihaddcsi. which engages the mind joyfully texts record these five songs merely Scholars have suggested that may be called rakti. The term rakti dhwanivisesha may be taken th as Tyagaraja’ s compositions and is not found in pre-17 century not as the Pancharatna kriti-s. Not to connote sruti and that its texts like Niruktam, Vyjayanti and only are these raga-s unsuitable for integration with music ensures a Amarakosam. -

The Gana Alankaras in Karnatic Music Compositions

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 7 July 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 THE GANA ALANKARAS IN KARNATIC MUSIC COMPOSITIONS Vinod K K Kochi, Kerala, India Abstract : As the name implies Alankaras are the factors of Kritis (classical songs) or ganas, which adorn the musical compositions. So, these are known as ‘Ganalankaras’. There are different types of Ganalankaras. The great composers of Karnatic music used varieties of the alankaras regularly as their signature in the compositions. The alankaras enhance the beauty of a kriti to a large extent. This article deals with the major Ganalankaras used by the great composers of Karnatic music. Index words : - Gana-alankaras, Sangathis, Chittaswaras, Madhyamakala sahitya, Swrakshara, Swarasahitya, Cholkkettu swara, Cholkkettu swara sahitya, Yathi. INTRODUCTION Alankaras are parts of musical compositions which provide attractive musical variations in the structure of the compositions. They produce a refreshing effect on singers or musicians and to the listeners alike when it is heard or rendered. The main types of ganalankaras found in the kritis of eminent Vaggeyakaras are Sangathis, Chittaswaras, Madhyamakala sahitya, Swrakshara, Swarasahitya, Cholkkettu swara, Cholkkettu swara sahitya and Yathi. Many great vaggeyakaras – [the composers who create both ‘vag’ and ‘geya” or sahitya and swara or lyrics and tunes of classical compositions] - have their own special area of expertise in the realm of alankaras. We can see the types of the above ganalankaras in detail. Various types of Gana Alankaras 1. Sangathis Sangathis are the variations given to the tune of lines of a kriti or these are the step by step musical changes given to the dhatu of a song when repeating the same line. -

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

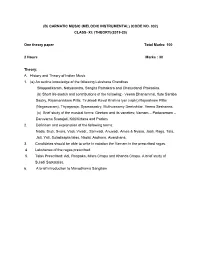

Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrumental) (Code No

(B) CARNATIC MUSIC (MELODIC INSTRUMENTAL) (CODE NO. 032) CLASS–XI: (THEORY)(2019-20) One theory paper Total Marks: 100 2 Hours Marks : 30 Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) An outline knowledge of the following Lakshana Grandhas Silappadikaram, Natyasastra, Sangita Ratnakara and Chaturdandi Prakasika. (b) Short life sketch and contributions of the following:- Veena Dhanammal, flute Saraba Sastry, Rajamanikkam Pillai, Tirukkodi Kaval Krishna lyer (violin) Rajaratnam Pillai (Nagasvaram), Thyagaraja, Syamasastry, Muthuswamy Deekshitar, Veena Seshanna. (c) Brief study of the musical forms: Geetam and its varieties; Varnam – Padavarnam – Daruvarna Svarajati, Kriti/Kirtana and Padam 2. Definition and explanation of the following terms: Nada, Sruti, Svara, Vadi, Vivadi:, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Amsa & Nyasa, Jaati, Raga, Tala, Jati, Yati, Suladisapta talas, Nadai, Arohana, Avarohana. 3. Candidates should be able to write in notation the Varnam in the prescribed ragas. 4. Lakshanas of the ragas prescribed. 5. Talas Prescribed: Adi, Roopaka, Misra Chapu and Khanda Chapu. A brief study of Suladi Saptatalas. 6. A brief introduction to Manodhama Sangitam CLASS–XI (PRACTICAL) One Practical Paper Marks: 70 B. Practical Activities 1. Ragas Prescribed: Mayamalavagowla, Sankarabharana, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Kambhoji, Madhyamavati, Arabhi, Pantuvarali Kedaragaula, Vasanta, Anandabharavi, Kanada, Dhanyasi. 2. Varnams (atleast three) in Aditala in two degree of speed. 3. Kriti/Kirtana in each of the prescribed ragas, covering the main Talas Adi, Rupakam and Chapu. 4. Brief alapana of the ragas prescribed. 5. Technique of playing niraval and kalpana svaras in Adi, and Rupaka talas in two degrees of speed. 6. The candidate should be able to produce all the gamakas pertaining to the chosen instrument. -

University of Kerala Ba Music Faculty of Fine Arts Choice

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA COURSE STRUCTURE AND SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE IN MUSIC BA MUSIC UNDER FACULTY OF FINE ARTS CHOICE BASED-CREDIT-SYSTEM (CBCS) Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation (2021 Admission onwards) 1 Revised Scheme & Syllabus – 2021 First Degree Programme in Music Scheme of the courses Sem Course No. Course title Inst. Hrs Credit Total Total per week hours credits I EN 1111 Language course I (English I) 5 4 25 17 1111 Language course II (Additional 4 3 Language I) 1121 Foundation course I (English) 4 2 MU 1141 Core course I (Theory I) 6 4 Introduction to Indian Music MU 1131 Complementary I 3 2 (Veena) SK 1131.3 Complementary course II 3 2 II EN 1211 Language course III 5 4 25 20 (English III) EN1212 Language course IV 4 3 (English III) 1211 Language course V 4 3 (Additional Language II) MU1241 Core course II (Practical I) 6 4 Abhyasaganam & Sabhaganam MU1231 Complementary III 3 3 (Veena) SK1231.3 Complementary course IV 3 3 III EN 1311 Language course VI 5 4 25 21 (English IV) 1311 Language course VII 5 4 (Additional language III ) MU1321 Foundation course II 4 3 MU1341 Core course III (Theory II) 2 2 Ragam MU1342 Core course IV (Practical II) 3 2 Varnams and Kritis I MU1331 Complementary course V 3 3 (Veena) SK1331.3 Complementary course VI 3 3 IV EN 1411 Language course VIII 5 4 25 21 (English V) 1411 Language course IX 5 4 (Additional language IV) MU1441 Core course V (Theory III) 5 3 Ragam, Talam and Vaggeyakaras 2 MU1442 Core course VI (Practical III) 4 4 Varnams and Kritis II MU1431 Complementary -

Sri Kamalamba Nava Aavarana Kritis

Sri Kamalamba Nava Aavarana Kritis Out of his devotion to Sri Kamalamba, (one of the 64 Sakti Peethams in India), the celebrated deity at the famous Tyagaraja Temple in Tiruvarur and his compassion for all bhaktas, Sri Muthuswamy Dikshitar composed the Kamalamba Navavarana kritis, expounding in each of the nine kritis, the details of the each avarana of the Sri Chakra, including the devatas and the yoginis. Singing these kritis with devotion, sraddha and understanding would be the easy way to Sri Vidya Upasana. Kamala is one of the ten maha vidyas, the principle deities of the Shaktha tradition of Tantra. But, the Sri Kamalamba referred to by Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar in this set of kritis, is the Supreme Divine Mother herself. The immediate inspiration to Dikshitar was, of course, Sri Kamalamba (regarded one of the sixty-four Shakthi centers), the celebrated deity at the famous temple of Sri Tyagaraja and Sri Nilothpalambika in Tiruvavur. Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar follows the Smahara krama, the absorption path, of Sri Chakra puja and proceeds from the outer avarana towards the Bindu in the ninth avarana at the center of the Sri Chakra. At each avarana, he submits his salutation and worships the presiding deity, the yogini (secondary deity) and the attendant siddhis of that avarana; and describes the salient features of the avarana according to the Kadi School of the Dakshinamurthy tradition of Sri Vidya. It is in effect both worship and elucidation. Dikshitar had developed a fascination for composing a series of kritis on a composite theme, perhaps in an attempt to explore the various dimensions of the subject. -

Carnatic Music Theory Year Ii

CARNATIC MUSIC THEORY YEAR II BASED ON THE SYLLABUS FOLLOWED BY GOVERNMENT MUSIC COLLEGES IN ANDHRA PRADESH AND TELANGANA FOR CERTIFICATE EXAMS HELD BY POTTI SRIRAMULU TELUGU UNIVERSITY ANANTH PATTABIRAMAN EDITION: 2.1 Latest edition can be downloaded from https://beautifulnote.com/theory Preface This text covers topics on Carnatic music required to clear the second year exams in Government music colleges in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Also, this is the second of four modules of theory as per Certificate in Music (Carnatic) examinations conducted by Potti Sriramulu Telugu University. So, if you are a music student from one of the above mentioned colleges, or preparing to appear for the university exam as a private candidate, you’ll find this useful. Though attempts are made to keep this text up-to-date with changes in the syllabus, students are strongly advised to consult the college or univer- sity and make sure all necessary topics are covered. This might also serve as an easy-to-follow introduction to Carnatic music for those who are generally interested in the system but not appearing for any particular examination. I’m grateful to my late guru, veteran violinist, Vidwan. Peri Srirama- murthy, for his guidance in preparing this document. Ananth Pattabiraman Editions First published in 2010, edition 2.0 in 2018, 2.1 in 2019. Latest edition available at https://beautifulnote.com/theory Copyright This work is copyrighted and is distributed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. You can make copies and share freely. Not for commercial use. Read https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ About the author Ananth Pattabiraman is a musician. -

2013……….Dinakar Subramanian

Table of Contents From the President’s Desk……….Ravi Pillutla .................................................................................. 2 From the Publications & Outreach Committee……….Tyagarajan Suresh ....................................... 3 Roopa Mahadevan at Sruti’s composers’ day - September 7, 2013……….Dinakar Subramanian...... 4 Shujaat Khan – A Concert Review……….Allyn Miner ...................................................................... 4 Vijay Siva in concert – A Review……….Rajee Raman ........................................................................ 7 Sri Krishna Parijatham – A Review……….Anize Appel ..................................................................... 8 My Guru Shri R.K.Venkatarama Shastry - A humble tribute……….M.G.Chandramouli ................ 9 Shri Thiruvidaimarudur Rajagopalan (TR) Subramanian (1929-2013)…..Toronto Brothers ............. 14 Sangita-Kalanidhi Pinakapani Garu, M.D.(1913 - 2013)……….Prabhakar Chitrapu ........................ 17 Images from the 2013 season .............................................................................................................. 20 Images from the 2013 season .............................................................................................................. 21 Images from the 2013 season .............................................................................................................. 22 Images from the 2013 season ............................................................................................................. -

Shri Kamalamba Jayati

Shree Kamalaambaa Jayati (Avarana 9 of Navavarna Krithis) Ragam: Ahiri (14th melakartha Vakulabharanam janyam) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahiri Arohana: S R₁ M₁ G₃ M₁ P D₁ N₂ Ṡ (also S R₁ S G₃ M₁ P D₁ N₂ Ṡ[b]) Avarohaṇa : Ṡ N₂ D₁ P M₁ G₃ R₁ S || Talam: Rupakam(2 kalai) Composer: Muthuswami Dikshitar Version: D.K. Jayaraman (http://www.shivkumar.org/music/originals/navavarnams/10-srikamalambajayati- ahiri-dkj.mp3 ) Youtube Class: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=om5TFaT9aSw MP3 Class: http://www.shivkumar.org/music/kamalamba-jayati-ahiri-class.mp3 Pallavi Shri Kamalaambaa Jayati Ambaa Shri Kamalaambaa Jayati Jagadaambaa Shri Kamalaambaa Jayati Shringaara Rasa Kadambaa Madambaa Shri Kamalaambaa Jayati Chidbimbaa Pratibimbendu Bimbaa Shri Kamalaambaa Jayati Shreepura Bindu Madhyastha Chintaamani Mandirastha Shivaakaara Manchasthita Shivakaameshaankasthaa Anupallavi Sukara-ananaadya-arccita Mahaa-tripura Sundarim Raajaraajeshvareem Shreekara Sarva-ananda-maya Chakra-vaasinim Suvaasinim Chintayeham Divaakara Sheetakirana Paavakaadi Vikaasakarayaa Bheekara Taapa-traya-adi Bhedana Dhurinatarayaa Paakaripu Pramukhaadi Praarthita-Sukalebarayaa Praakatya Paraaparayaa Paalitodayaakarayaa Charanam Shrimaatre Namaste Chinmaatre Sevita Ramaa Harisha Vidhaatre Vaamaadi Shaktipujita Paradevataayaah Sakalam Jaatam Kaamaadi Dvaadashabhir-upaasita Kaadi Haadi Saadi Mantra-rupinyaah Premaaspada Shiva Guruguha Jananyaam Pritiyukta Macchittam Vilayatu Brahmamaya Prakaashini Naamaroopa Vimarshini Kaamakalaa Pradarshini Saamarasya Nidarshini Meaning (From Todd Mc Comb's web page: http://www.medieval.org/music/world/carnatic/lyrics/srao/kamala.html): Hail ("jayati") my mother ("amba"), Shri Kamalamba. Hail ("jayati") to the mother of the world, Shri Kamalamba. You are the personification of Shringara Rasa, the essence of the sentiment ("rasa") of love ("sringaara"). Oh my mother, You are the reflection ("pratibimbe") of the entity ("bimba") of consciousness ("chid"), Cidbimba, residing at the orb of the moon that shows the reflection of the original orb, void of consciousness.