Cinema, Computers, and War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"ALL OUT!!" Is the First Ever Animated TV Show About Rugby! to Be Produced by TMS and MADHOUSE! Broadcast Will Begin I

N E W S R E L E A S E April 4th, 2016 TMS Entertainment Co., Ltd. "ALL OUT!!" is the first ever animated TV show about rugby! To be produced by TMS and MADHOUSE! Broadcast will begin in the fall of 2016 A team assembled from the sports production elite! A portrayal of the fire of youth! TMS Entertainment Co., Ltd. (Head office: Nakano-ku, Tokyo, President: Yoshiharu Suzuki, referred to below as TMS), will produce an animated TV series based on "ALL OUT!!", the authentic high school rugby manga created by Shiori Amase (currently serialized in Kodansha's 'Morning Two'). They will make the announcement of the broadcast beginning in the fall of 2016, and release teaser visuals. [Official TV show website] http://allout-anime.com/ [Official Twitter account] https://twitter.com/allout_anime [Official Facebook page] https://www.facebook.com/allout.animation ■ About ALL OUT!! "ALL OUT!!" is a high school rugby comic loved for its dynamic production and sensitive psychological portrayal. It has been serialized in the monthly "Morning Two" since 2012, and the comic has now been published up to Volume 7 (referred to below as "ongoing publication".) Volume 8 is scheduled for publication on February 23rd, with the simultaneous release of a Special Edition Volume 8 bundled with an original drama CD featuring the same cast as the animated TV show, as well as a Special Edition Volume 1 consisting of the previously published Volume 1 bundled with the original drama CD. ■ A stellar team has been assembled! The show is directed by Kenichi Shimizu, who has worked on "Parasyte -The Maxim-", "Avengers Confidential: Black Widow & Punisher", etc., and is widely active both in Japan and overseas. -

New Jersey in Focus: the World War I Era 1910-1920

New Jersey in Focus: The World War I Era 1910-1920 Exhibit at the Monmouth County Library Headquarters 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, New Jersey October 2015 Organized by The Monmouth County Archives Division of the Monmouth County Clerk Christine Giordano Hanlon Gary D. Saretzky, Curator Eugene Osovitz, Preparer Produced by the Monmouth County Archives 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, NJ 07726 New Jersey in Focus: The World War I Era, 1910-1920 About one hundred years ago, during the 1910-1920 decade in America, the economy boomed and the Gross National Product more than doubled. Ten million Americans bought automobiles, most for the first time. Ford’s Model T, produced with then revolutionary assembly line methods, transformed family life for owners. Such personal “machines” led to paved roads and the first traffic light, reduced the need for blacksmiths and horses, increased the demand for auto mechanics and gas stations, and, when not caught up in traffic jams, sped up daily life. Some owners braved dirt roads to drive to the Jersey Shore, where thousands thronged to see the annual Baby Parade in Asbury Park. While roads at the start of the decade were barely adequate for travel in the emerging auto boom, New Jersey became a leader in the advocacy and construction of improved thoroughfares. Better road and rail transportation facilitated both industrial and agricultural production, bringing such new products as commercially grown blueberries from Whitesbog, New Jersey, to urban dwellers. In the air, history was made in 1912, when the first flight to deliver mail between two government post offices landed in South Amboy. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

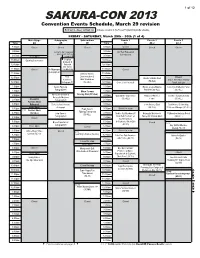

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

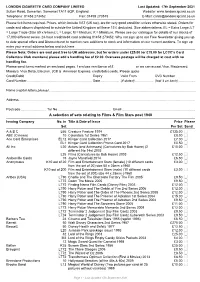

LCCC Thematic List

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

Aachi Wa Ssipak Afro Samurai Afro Samurai Resurrection Air Air Gear

1001 Nights Burn Up! Excess Dragon Ball Z Movies 3 Busou Renkin Druaga no Tou: the Aegis of Uruk Byousoku 5 Centimeter Druaga no Tou: the Sword of Uruk AA! Megami-sama (2005) Durarara!! Aachi wa Ssipak Dwaejiui Wang Afro Samurai C Afro Samurai Resurrection Canaan Air Card Captor Sakura Edens Bowy Air Gear Casshern Sins El Cazador de la Bruja Akira Chaos;Head Elfen Lied Angel Beats! Chihayafuru Erementar Gerad Animatrix, The Chii's Sweet Home Evangelion Ano Natsu de Matteru Chii's Sweet Home: Atarashii Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Ha Ao no Exorcist O'uchi Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Jo Appleseed +(2004) Chobits Appleseed Saga Ex Machina Choujuushin Gravion Argento Soma Choujuushin Gravion Zwei Fate/Stay Night Aria the Animation Chrno Crusade Fate/Stay Night: Unlimited Blade Asobi ni Iku yo! +Ova Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Works Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Clannad Figure 17: Tsubasa & Hikaru Azumanga Daioh Clannad After Story Final Fantasy Claymore Final Fantasy Unlimited Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children B Gata H Kei Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Baccano! R2 Freedom Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Colorful Fruits Basket Bakemonogatari Cossette no Shouzou Full Metal Panic! Bakuman. Cowboy Bebop Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu + TSR Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Coyote Ragtime Show Furi Kuri Irohanihoheto Cyber City Oedo 808 Fushigi Yuugi Bakuretsu Tenshi +Ova Bamboo Blade Bartender D.Gray-man Gad Guard Basilisk: Kouga Ninpou Chou D.N. Angel Gakuen Mokushiroku: High School Beck Dance in -

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, Et Al

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, et al. Summer Camp Scares I Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th I Still Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th Part 2 All The Boys Love Mandy Lane Friday the 13th Part III The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) Sleepaway Camp The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers House of Wax Sleepaway Camp III: Teenage Wasteland Wolf Creek The Final Girls Wolf Creek 2 Stage Fright Psycho Beach Party The Burning Club Dread Campfire Tales Disturbia Addams Family Values It Follows The Devil’s Rejects Creepy Cabins in the Woods Blood Beach Cabin Fever The Lost Boys The Cabin in the Woods Straw Dogs The Evil Dead The Town That Dreaded Sundown Evil Dead 2 VACATION NIGHTMARES IT Evil Dead Hostel Ghost Ship Tucker and Dale vs Evil Hostel: Part II From Dusk till Dawn The Hills Have Eyes Death Proof Eden Lake Jeepers Creepers Funny Games Turistas Long Weekend AQUATIC HORROR, SHARKS, & ANIMAL ATTACKS Donkey Punch Jaws An American Werewolf in London Jaws 2 An American Werewolf in Paris Jaws 3 Prey Joyride Jaws: The Revenge Burning Bright The Hitcher The Reef Anaconda Borderland The Shallows Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid Tourist Trap 47 Meters Down Lake Placid I Spit On Your Grave Piranha Black Water Wrong Turn Piranha 3D Rogue The Green Inferno Piranha 3DD Backcountry The Descent Shark Night 3D Creature from the Black Lagoon Deliverance Bait 3D Jurassic Park High Tension Open Water The Lost World: Jurassic Park II Kalifornia Open Water 2: Adrift Jurassic Park III Open Water 3: Cage Dive Jurassic World Deep Blue Sea Dark Tide mrandmrshalloween.com. -

Download Black Lagoon

Download black lagoon Watch Full Episodes of Black Lagoon at Soul-Anime. Soul-Anime is the best website to watch Black Lagoon!!! download or watch full episodes for free. Black Lagoon s01 cover. Black Lagoon (–) Season 1 Free Download. Genre: Animation | Action | Adventure | Comedy | Crime | Mystery. Black Lagoon: A Netflix Original A gangster named Chin lures Dutch and the crew of the Black Lagoon into a battle at sea against . Available to download. Album name: Black Lagoon OP Single - Red fraction. Number of Files: 3. Total Filesize: MB Date added: Feb 24th, New! Download all songs at. Black Lagoon. ON-GOING. Hiroe, Rei (Story & Art) Chapter 5 - Das Wieder Erstephen Des Adlers Part 1, /09/27, Download · Chapter 6 - Das Wieder. Preview and download your favorite episodes of Black Lagoon, Season 1, or the entire season. Buy the season for $ Episodes start at. Discover & share this Black Lagoon GIF with everyone you know. GIPHY is how you Black Lagoon. Black Lagoon: The Black Lagoon Torrent Download - Black-Lagoon-Anime-Revy-Pirates-of-the-Caribbeanjpeg × ピクセル. Buy Soundraid: Read Digital Music Reviews - English. limit my search to r/blacklagoon (0 children). I don't know of any torrent but you can watch and download episodes on kissanime. "I was born into a mentally ill family. My sister was the officially crazy one, but really we were all nuts." So begins My Sister from the Black Lagoon, Laurie Fox's. Zerochan has Black Lagoon anime images, wallpapers, HD wallpapers, Android/iPhone wallpapers, fanart, Black Lagoon download Black Lagoon image. Download page for Creature from the Black Lagoon (L-4) ROM for M.A.M.E. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Cinematicambix: Cinematic Sound in Virtual Reality Adam Schwartz B.S., Audio Technology from American University, 2003 Thesis Su

CinematicAmbiX: Cinematic Sound in Virtual Reality Adam Schwartz B.S., Audio Technology from American University, 2003 Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art in Art & Technology in the Welch Center for Graduate and Professional Studies of Goucher College November 25, 2020 X Andrew Bernstein Capstone Advisor Schwartz 1 I authorize Goucher College to lend this thesis, or reproductions of it, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Copyright ©2020 by Adam Schwartz All rights reserved Schwartz 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my Capstone Committee – Andrew Bernstein, Mary Helena Clark, and Damian Catera. Your thoughtful advice and guidance have made it possible for me to complete this work during my Capstone and throughout my time in the Art and Technology MFA program. Thanks also to my wife Lindsay whose love and support made this work possible. And of course, thanks to my incredible, brilliant daughter Millie for putting a smile on my face, regardless of my level of stress. Thanks to Ryan Murray for being my technical advisor while getting up and running in VR and for being my only trusted beta tester. Thanks to Elsa Lankford for your encouragement and support to pursue this degree. Finally, thank you to all my Goucher College Art and Technology classmates whose talent and creativity inspired me throughout this journey. Schwartz 3 ABSTRACT CinematicAmbiX is a three-movement piece of virtual reality art that is focused on sound for film. -

Scott, Natalie (2015) Screams Underwater. Submerging The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sunderland University Institutional Repository Scott, Natalie (2015) Screams Underwater. Submerging the Authorial Voice: A Polyphonic Approach to Retelling the Known Narrative in Berth - Voices of the Titanic, A Poetry Collection by Natalie Scott. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/6582/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Abstract This PhD thesis is comprised of my poetry collection: Berth - Voices of the Titanic (Bradshaw Books, 2012) and a critical commentary which discusses the collection both in printed and performed contexts. Berth is a collection of fifty poems taking a range of forms, including dramatic monologue, and found, sound and concrete poems. It was published and performed to coincide with the centenary of the Titanic disaster on April 14th 2012. The collection encourages an audience to see and hear Titanic in a distinctive way, through the poetic voices of actual shipyard workers, passengers, crew, animals, objects, even those of the iceberg and ship herself. Though extensively researched, it is not intended to be a solely factual account of Titanic’s life and death but a voiced exploration of the what-ifs, ironies, humour and hearsay, as well as painful truths, presented from the imagined perspective of those directly and indirectly linked to the disaster. The critical commentary introduces the notion of factional poetic storytelling and, supported by Julia Kristeva’s definition of intertextuality, considers the extent to which Berth is an intertext.