Spatial Memorializing of Atrocity in 1857

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

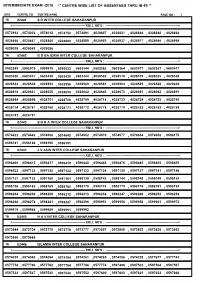

Centre List Dist 16

INTERMEDIATE EXAM -2016 ** CENTRE WISE LIST OF ABSENTEES THRU IB-89 ** DIST CENTRE CD CENTRE NAME PAGE NO : 1 16 02441 S D INTER COLLEGE SAHARANPUR <------------------------------------------------------------------------ ROLL NO'S : ------------------------------------------------------------------------> 0573992, 0574002, 0574012 ,,0574750 0574891, 4028807,,, 4028831 4028844 4028848, 4028864 4028866, 4028867, 4028884 ,,4028888 4028889, 4028903,,, 4028927 4028977 4028986, 4028998 4029029, 4029042, 4029056 16 02442 B D BAJORIA INTER COLLEGE SAHARANPUR <------------------------------------------------------------------------ ROLL NO'S : ------------------------------------------------------------------------> 0592899, 0592915, 0595515 ,,0595533 0603344, 0603362,,, 0603364 0603377 0603387, 0603417 0603420, 0603431, 0603438 ,,0603439 0603444, 4028502,,, 4028518 4028519 4028525, 4028528 4028533, 4028538, 4028553 ,,4028558 4028569, 4028581,,, 4028584 4028585 4028588, 4028609 4028618, 4028621, 4028635 ,,4028638 4028642, 4028643,,, 4028673 4028681 4028682, 4028691 4028694, 4028696, 4028701 ,,4028706 4028709, 4028718,,, 4028723 4028724 4028733, 4028745 4028754, 4028767, 4028768 ,,4028771 4028772, 4028778,,, 4028779 4028782 4028783, 4028789 4028793, 4028797 16 02443 S B B A INTER COLLEGE SAHARANPUR <------------------------------------------------------------------------ ROLL NO'S : ------------------------------------------------------------------------> 0574422, 0574442, 0574506 ,,0574543 0574552, 0574570,,, 0574577 0574654 0574658, 0596175 0596181, -

COMPUTER EVALUATION of ANTHROPOLOGICAL CENSUS DATA by Rex Richard Hutchens a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT O

Computer evaluation of anthropological census data Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hutchens, Rex Richard, 1942- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 14:15:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318606 COMPUTER EVALUATION OF ANTHROPOLOGICAL CENSUS DATA by Rex Richard Hutchens A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial ful fillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for per mission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be ob tained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below 4i 3-U-7X. -

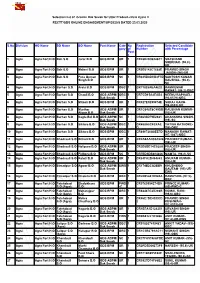

Kstuk Ds Ykhk Ls Oafpr Ifr Dh E`R;Q Ds Mijkur Fujkfjr Efgyk Isa'ku Ds Loz{Kk

ykHkkFkhZijd ,oa dY;k.kdkjh ;kstuk ds ykHk ls oafpr ifr dh e`R;q ds mijkUr fujkfJr efgyk isa'ku ds loZ{k.k esa ik;s x;s ik= ykHkkfFkZ;ksa dh lwph o"kZ 2018&19 Serial No. District Name Block Name Panchayat Name Village name Name father husband Name Category Name Bank Name Branch Name Account Number ifsc_cd 1 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND AMARPUR NAIN AMARPUR NAIN RESHO DEVI SUBHASH SC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK DEOBAND 6217000100004753 PUNB0621700 2 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND AMARPUR NAIN AMARPUR NAIN TULSA HARPAL SC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK DEOBAND 621700100062969 PUNB0621700 3 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI GEETA DEVI BHARAT SINGH SC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BASTAM 2464000100281646 PUNB0246400 4 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI BABITA TITU SC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BASTAM 2464000100282663 PUNB0246400 5 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI RAGHUVIRI LALLA SC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BASTAM 2464001700000707 PUNB0246400 6 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI SUNIRA PAWAN OBC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BASTAM 2464000100291148 PUNB0246400 7 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI SANTOSH RAMKISHAN SC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BASTAM 2464000100305672 PUNB0246400 8 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI DULARI LAKSHMICHAND OBC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BASTAM 2464000100292721 PUNB0246400 9 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI CHANDO SHERSINGH OBC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BASTAM 2464000100293872 PUNB0246400 10 SAHARANPUR DEOBAND ASADPUR KRANJALI ASADPUR KRANJALI RAJKUMARI VINOD SC PUNJAB -

India Rural Sociology Leadership Social Change Measurement Uttar Pradeshindia?

AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT I USEONLY WASHINGTON. D. C. 203323 BIBLIOGRAPHIC INPUT SHEET 46. F'RIPARV 1.'JRJECT Food production and nutrition AE30-0000-G635 r. L Ai-I )A ll+ I(ATION h. i '..dI Development--India 2. TITLE AND SUBTITLF Planned development and leadership in an Indian village 3, AUTHOR(S) Danda,A.K. 4. DOCUMENT DATE -T. NUMBER OF PAGES 6. ARC NUMBER 1966 373p. ARC 7. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS Cornell S. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (Sponsoring Or,nilzatlon, Publishers# Availability) (In Comparative studies in cultural change.Publication) 9. ABSTRACT 10. COUROL NUMBER 11. PRICE OF DOCUMENT 12. DESCRIPTORS 13. PROJECT NUMBER Government policies Planning India Rural sociology Leadership Social change Measurement Uttar PradeshIndia? AID 590-I (4-741 PLANNED DEVELOPMENT AND LEADERSHIP IN AN INDIAN VILLAGE by Ajit Kumar Danda Comparative Studies of Cultural Change Department of Aiachropology Cornell University Ithaca, Now York 1966 The wind of change is h icwing through the continent. Harold Macmillan - ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This analysis is one of the comparative studies of cul tural change undertaken by the Department of Anthropology in connection with contract AID/csd-296 between Cornell Univer sity and the Agency for International Development. The author owes thanks to the Project, the Department, and to A.I.D. for the opportunity and financial support that made this report possible. Needless to say, the opinions an conclusions set forth are those of the author and not of the Agency for Inter national Development. In submitting this document, the author would also like to express his deep appreciation and gratitude to Professor Morris E. -

Selection List of Gramin Dak Sevak for Uttar Pradesh Circle Cycle II RECTT/GDS ONLINE ENGAGEMENT/UP/2020/8 DATED 23.03.2020

Selection list of Gramin Dak Sevak for Uttar Pradesh circle Cycle II RECTT/GDS ONLINE ENGAGEMENT/UP/2020/8 DATED 23.03.2020 S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Agra Agra Fort H.O Bah S.O Jarar B.O GDS BPM UR 1 CR28E23D6248C7 SHASHANK SHEKHAR- (96.8)- UR 2 Agra Agra Fort H.O Bah S.O Maloni B.O GDS BPM UR 1 CR0E6142C7668E PRAMOD SINGH JADON- (96)-UR 3 Agra Agra Fort H.O Bah S.O Pura Guman GDS BPM SC 1 CR045D8DCD4F7D SANTOSH KUMAR Singh B.O KAUSHAL- (96.8)- SC 4 Agra Agra Fort H.O Barhan S.O Arela B.O GDS BPM OBC 1 CR71825AEA4632 RAMKUMAR RAWAT- (96.2)-OBC 5 Agra Agra Fort H.O Barhan S.O Chaoli B.O GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 CR7CD15A4EAB4 NEENU RAPHAEL- Dak Sevak 7 (95.6579)-OBC 6 Agra Agra Fort H.O Barhan S.O Mitaoli B.O GDS BPM UR 1 CR027E3E99874E SURAJ GARG- (96.8333)-UR 7 Agra Agra Fort H.O Barhan S.O Murthar GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR1C648E8C49DB RAUSHAN KUMAR- Alipur B.O Dak Sevak (95)-UR 8 Agra Agra Fort H.O Barhan S.O Nagla Bel B.O GDS ABPM/ SC 1 CR4633D79E2881 AKANKSHA SINGH- Dak Sevak (95)-SC 9 Agra Agra Fort H.O Barhan S.O Siktara B.O GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 CR488A8CFEFAE YATISH RATHORE- Dak Sevak D (95)-OBC 10 Agra Agra Fort H.O Barhan S.O Siktara B.O GDS BPM OBC 1 CR896726A8EE7D MANASHI RAWAT- (97.1667)-OBC 11 Agra Agra Fort H.O Bhadrauli S.O Bitholi B.O GDS BPM UR 1 CR2A9AAD35A524 PRADEEP KUMAR- (96)-UR 12 Agra Agra Fort H.O Bhadrauli S.O Holipura B.O GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR3E6BE14C928A PRADEEP SINGH- Dak Sevak (95)-UR 13 Agra Agra Fort H.O Bhadrauli S.O Pidhora B.O -

II/2019 UTTAR PRADESH CIRCLE Applications Are Invited by the Respe

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 UTTAR PRADESH CIRCLE RECTT/GDSRECTT/GDS ONLINE ONLINE ENGAGEMENT/UP/2020/8 ENGAGEMENT/UP/2020/8 DATED 23.03.2020 Applications are invited by the respective recruiting authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of GDS Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank (IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device, ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However,the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the GDS Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same GDS Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM etc.In some of the Branch Post Offices, the BPM has to do all the work of BPM/ABPM. -

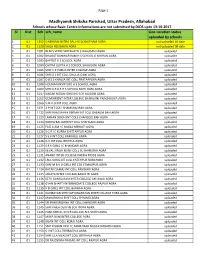

Center Information Not Updated by DIOS 13102017.Xlsx

Page 1 Madhyamik Shiksha Parishad, Uttar Pradesh, Allahabad Schools whose Basic Centre Informations are not submitted by DIOS upto 13-10-2017 Sl Dist Sch sch_name Geo-Location status uploaded by schools 1 01 1352 S NEKRAM NETRA PAL H S SCH KITHAM AGRA not uploaded till date 2 01 1620 SHILA HSS BAGIA AGRA not uploaded till date 3 01 1001 BENI S VEDIC VIDYAVATI I C BALUGANJ AGRA uploaded 4 01 1002 BHAGAT KANWAR RAM H S SCHOOL G M KHAN AGRA uploaded 5 01 1003 BAPTIST H S SCHOOL AGRA uploaded 6 01 1004 CHITRA GUPTA H S SCHOOL SHAHGANJ AGRA uploaded 7 01 1005 SHRI C P PUBLIC INTER COLLEGE AGRA uploaded 8 01 1006 SHRI D J INT COLL DHULIA GANJ AGRA uploaded 9 01 1007 D B S S KHALSA INT COLL PRATAPPURA AGRA uploaded 10 01 1008 HOLMAN INSTITUTE H S SCHOOL AGRA uploaded 11 01 1009 SHRI K R B R H S SCHOOL MOTI GANJ AGRA uploaded 12 01 1037 NAGAR NIGAM GIRLS HS SCH TAJGANJ AGRA uploaded 13 01 1052 GOVERMENT INTER COLLEGE SHAHGANJ PNACHKUIYA AGRA uploaded 14 01 1066 S M A O INT COLL AGRA uploaded 15 01 1071 A P INT COLL SHAMSHADBAD AGRA uploaded 16 01 1122 SHRI RAM SAHAY VERMA INT COLL BASAUNI BAH AGRA uploaded 17 01 1123 LAKHAN SINGH INT COLL CHANGOLI BAH AGRA uploaded 18 01 1124 RADHA BALLABH INT COLL SHAHGANJ AGRA uploaded 19 01 1125 FAIZ A AM I C NAGLA MEWATI AGRA uploaded 20 01 1126 S G R I C KURRA CHITTARPUR AGRA uploaded 21 01 1127 S S V INT COLL KARKAULI AGRA uploaded 22 01 1128 G V INT COLL BRITHLA AGRA uploaded 23 01 1129 S R K GIRLS I C KHANDARI AGRA uploaded 24 01 1130 KEVAL SINGH M INT COLL SUTHARI BAH AGRA uploaded 25 01 1131 ANAND INTER -

Downloaded from सी�नयर �लट OBC डॉ啍यूम�ट वे�र�फकेशन के �लए �त�थ �नधा셍रण स�हत Letter Number 7201 Date 01-10-2019 S.NO

सी�नयर �लट GENERAL डॉ啍यूम�ट वे�र�फकेशन के �लए �त�थ �नधा셍रण स�हत Letter number 7201 date 01-10-2019 S.N Name Fname PAddress i=kad fnukad cqykok frfFk O. GENERAL 1 SUBHAM ARVIND SINGH WARI,HAMIDPUR,KADIPUR,SULTAN 7202 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SINGH PUR Pin.228145 (UP) 2 Sarvesh shukla raju Chandra Rampur Kotwa lalgopalganj kunda 7203 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 shukla Pratapgarh 3 RISHIKESH PREM KISHORE 4121, Chowk kaseru walan pahar 7204 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 ganj new delhi:110055 4 SHUBHAM RAJENDRA SINGH vill-post- Abhaypur Dist Fatehpur 7205 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SINGH pin code 212665 5 Vinay tiwari Ram prakash Village/post loyabadshahpur 7206 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 tiwari district etah uttarpradesh 207001 6 SAURABH DIXIT ANIL KUMAR shiv shakti public school durga 7207 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 DIXIT nagar nagla kishan lal tedi bagiya agra 7 MANISH DEV SHIV KUMAR VILL-POST-ABHAYPUR DIST- 7208 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 GAUTAM SINGH DownloadedFATEHPUR UTTAR PRADESH from PIN- 212665 8 KULDIP BRAJESH SHARMA MOH.www.upsrtc.com HANUMAN NAGAR 7209 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SHARMA FATEHABAD TEHSIL- FATEHABAD DIST- AGRA UP 283111 सी�नयर �लट GENERAL डॉ啍यूम�ट वे�र�फकेशन के �लए �त�थ �नधा셍रण स�हत Letter number 7201 date 01-10-2019 S.N Name Fname PAddress i=kad fnukad cqykok frfFk O. GENERAL 9 SHIVAM HANUMANT VILL GARHI DALEL POST GARHI 7210 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 CHAUHAN SINGH CHAUHAN RAMDHAN DIST ETAWAH PINCODE 206245 10 NISHANT JAGMEHAR Village- Babupura 7211 01/10/2019 14-10-2019 SHARMA SHARMA Post- Nanauta District- Saharanpur Pin- 247452 11 DEEPAK SARVESH KUMAR PURANA -

1 Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Tehsil Koil

Format for Advertisement in Website Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Uttar Pradesh, as per following details: Fixed Fee / Security Estimated monthly Type of Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Mode of Minimum Bid Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category Finance to be arranged by the applicant Deposit (Rs. Sales Potential # Site* the site (in Sq. M.). * Selection amount (Rs. In In Lakhs) Lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC, SC CC-1, SC PH ST, ST CC-1, ST PH OBC, OBC CC- CC / DC / Estimated fund Estimated working Draw of Regular / 1, OBC PH CFS required for MS+HSD in Kls Frontage Depth Area capital requirement Lots / Rural development of for operation of RO Bidding infrastructure at RO OPEN, OPEN CC- 1, OPEN CC- 2,OPEN-PH Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Draw of 1 Tehsil Koil, Dist Aligarh ALIGARH RURAL 90 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dhansia, Block Jewar, Tehsil Jewar,On Jewar to GAUTAM BUDH Draw of 2 Khurja Road, dist GB Nagar NAGAR RURAL 160 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dewarpur Pargana & Distt. Auraiya Bidhuna Auraiya Draw of 3 Road Block BHAGYANAGAR AURAIYA RURAL 150 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Kudarkot on Kudarkot Ruruganj Road, Block Draw of 4 AIRWAKATRA AURAIYA RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 5 Village Behta Block Saurikh on Saurikh to Vishun Garh Road KANNAUJ RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 6 Village Nadau, -

Haryana Roadways, Yamuna Nagar List of Ineligible Application for the Post of Driver in Haryana Sr

Haryana Roadways, Yamuna Nagar List of Ineligible application for the post of Driver in Haryana Sr. Form Name Father's Name Date of Category Address Reason No. No. birth 1 2 Lekh Ram Multani Ram 01/05/1975 BC-A Village Mamidi, PO Aurangabad, Tehsil Jagadhri, Distt. Transport Licence only Yamuna Nagar 2 3 Suresh Kumar Hari Ram 27/01/1975 BC-A Village Sandala, PO Gumthala Rao, Tehsil Radaur, Experince of Truck Distt. Yamuna Nagar 3 4 Manjit Singh GuljitSingh 11/09/1978 Gen HNO 16/2, Singhpura Mor, Paonta Road, Chhchhrauli, Transport Licence only Distt. Yamuna Nagar 4 5 Sandeep Singh Uday Singh 15/02/1993 BC-B HNO 103, Garhi Ajima Majramo, Tehsil Narnond, Distt. HTV issue date not clear Hissar 5 7 Roshan Lal Mohinder Ram 09/06/1985 SC Village Bhagwan Pur, PO Manka Manki, Tehsil Experince of passenger not attached Jagadhri, Distt. Yamuna Nagar 6 8 Mohamad Rafi Nasib Ali 03/03/1985 BC-A Village Abdulagarh, Tehsil Barara, PO Kaserla Kalan, DOB difference in Licence & Distt. Ambala Certificate 7 9 Nirmal Singh Jai Singh 31/03/1974 BC-A ESM Village Rattu Wala, PO Sadhaura, Tehsil Bilaspur, Proff Original HTV DL Issued date Distt. Yamuna Nagar HTV DL 8 10 Sanjeev Kumar Jagdish Lal 12/12/1979 BC-A Village Harnouli, PO Bherthal, Tehsil Jagadhri, Distt. Experience less then 3 years Yamuna Nagar 9 11 Surinder Kumar Maluk Singh 09/01/1978 Gen VPO Shambhu Wala, Tehsil Nahan, Distt. Sirmour, H.P Experience less then 3 years 10 12 Rajiv Singh Dharam Singh 28/03/1972 Gen HNO 805, VPO Barara, Distt. -

Annexure-IX LIST of 5043 SCHOOLS for SMART CLASSROOM - UTTAR PRADESH S

Annexure-IX LIST OF 5043 SCHOOLS FOR SMART CLASSROOM - UTTAR PRADESH S. No. District Name Block Name Cluster Name Cluster Code School Name UDISE Code 1 AGRA-0915 FATEHPUR SIKRI-091507 UNDERA 915070048 J.H.S.DEVNARI 9150705002 2 AGRA-0915 FATEHABAD-091511 TIBAHA 915110058 J.H.S. PAKKA PURA 9151113601 3 AGRA-0915 SAIYAN-091514 TEHRA 915140101 J.H.S JHILRA (COMPOSITE) 9151405502 4 AGRA-0915 FATEHABAD-091511 TARAULI GUJER 915110060 J.H.S.BEGAMPUR 9151109904 5 AGRA-0915 BAROLI AHEER-091504 TANORA NOORPUR 915040030 J.H.S.BAROLI GUJAR (COMPOSITE) 9150407202 6 AGRA-0915 KHERAGARH-091512 SITOLI 915120090 G.J.H.S.KHERAGARH-2 9151206614 7 AGRA-0915 SHAMSHABAD-091515 SIKTARA 915150111 G.J.H.S.SHAMSHABAD (COMPOSITE) 9151509912 8 AGRA-0915 BAH-091503 SIDHAVALI 915030020 J.H.S.HIGOT KHERA 9150307902 9 AGRA-0915 BAROLI AHEER-091504 SHYAMO 915040027 J.H.S.AKBERPUR (COMPOSITE) 9150404002 10 AGRA-0915 KHERAGARH-091512 SARENDA 915120086 J.H.S.BARVAR 9151204902 11 AGRA-0915 ETMADPUR-091506 SANVAI 915060042 G.J.H.S.ETMADPUR (COMPOSITE) 9150600112 12 AGRA-0915 SAIYAN-091514 SAIYAN 915140099 J.H.S.NADEEM 9151400302 13 AGRA-0915 BAROLI AHEER-091504 ROHTA 915040026 G.J.H.S.ROHTA (COMPOSITE) 9150402904 14 AGRA-0915 JAGNER-091508 RICHHOHA 915080069 J.H.S BHOJPURA 9150802702 15 AGRA-0915 KHERAGARH-091512 RASOOLPUR 915120087 J.H.S DANDA 9151203302 16 AGRA-0915 M.C.AGRA CITY-091517 RAKABGANG WARD 915170005 G.J.H.S.IDGAH 9151707402 17 AGRA-0915 ACCHNERA-091502 PURAMANA 915020009 G.J.H.S.KIRAWALI 9150200208 18 AGRA-0915 JAITPUR KALAN-091509 PARNA 915090076 G.J.H.S.PARNA 9150907704 19 AGRA-0915 SAIYAN-091514 PANOTA 915140107 J.H.S.BHAWAN PURA (COMPOSITE) 9151403702 20 AGRA-0915 JAGNER-091508 NAUNI 915080065 J.H.S.NAGLA BHAJNA 9150809001 21 AGRA-0915 ETMADPUR-091506 NAGLA BEL 915060044 J.H.S. -

I. Background of the Topic

Surabhi Singh* ABSTRACT Rankhandi and three other villages (Jhabiran, Nagal, and Jakhwala) in Saharanpur district of Western Uttar Pradesh in India have sought attention of Anthropologists and Sociologists of Cornell University, other American Universities and Indian Universities since last 65 years. Many research studies have been conducted in these villages on different themes such as village social system, rural social structure, caste and inter-caste relations, social network, communication, women status etc. In the present research paper an attempt has been made to review these studies conducted in these four villages by understanding their historical underpinnings and current discourse. The main objective of this research paper is to review these field and explore this region in the larger context of sociological studies. There is a need to review these studies and re-study these four villages from the standpoint of rural-urban articulations, economic, social, political and cultural interfaces. This is the best sample of villages from the standpoint of many villages with longitudinal studies. At the same time, from the demographic point of view, Rankhandi and Nagal represent large villages and Jhabiran and Jakhwala represent small villages. I. Background of the Topic After Independence India was facing many problems related to development such as; health, education, communication, roads, transportation, infrastructure, agriculture and many more. More than three fourth of the population was living in rural areas and primarily depended on agriculture for their livelihoods and sustenance. Therefore, it was vital to frame integrated community development plans for rural development. First Prime Minister of India, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru invited academicians, agriculture scientists and social scientists in India to carry out research projects which can be useful in designing development programmes and projects in India.