Interview a Trip to See the Prince of Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa

Safrica Page 1 of 42 Recent Reports Support HRW About HRW Site Map May 1995 Vol. 7, No.3 SOUTH AFRICA THREATS TO A NEW DEMOCRACY Continuing Violence in KwaZulu-Natal INTRODUCTION For the last decade South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal region has been troubled by political violence. This conflict escalated during the four years of negotiations for a transition to democratic rule, and reached the status of a virtual civil war in the last months before the national elections of April 1994, significantly disrupting the election process. Although the first year of democratic government in South Africa has led to a decrease in the monthly death toll, the figures remain high enough to threaten the process of national reconstruction. In particular, violence may prevent the establishment of democratic local government structures in KwaZulu-Natal following further elections scheduled to be held on November 1, 1995. The basis of this violence remains the conflict between the African National Congress (ANC), now the leading party in the Government of National Unity, and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), the majority party within the new region of KwaZulu-Natal that replaced the former white province of Natal and the black homeland of KwaZulu. Although the IFP abandoned a boycott of the negotiations process and election campaign in order to participate in the April 1994 poll, following last minute concessions to its position, neither this decision nor the election itself finally resolved the points at issue. While the ANC has argued during the year since the election that the final constitutional arrangements for South Africa should include a relatively centralized government and the introduction of elected government structures at all levels, the IFP has maintained instead that South Africa's regions should form a federal system, and that the colonial tribal government structures should remain in place in the former homelands. -

Provincial Road Network Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality (KZ216)

O O O L L Etsheni P Sibukosethu Dunstan L L Kwafica 0 1 L 0 2 0 1 0 3 0 3 74 9 3 0 02 2 6 3 4 L1 .! 3 D923 0 Farrell 3 33 2 3 5 0 Icabhane 6 L0 4 D 5 2 L 3 7 8 3 O O 92 0 9 0 L Hospital 64 O 8 Empola P D D 1 5 5 18 33 L 951 9 L 9 D 0 0 D 23 D 1 OL 3 4 4 3 Mayiyana S 5 5 3 4 O 2 3 L 3 0 5 3 3 9 Gobhela 2 3 Dingezweni P 5 D 0 8 Rosettenville 4 L 1 8 O Khakhamela P 1 6 9 L 1 2 8 3 6 1 28 2 P 0 L 1 9 P L 2 1 6 O 1 0 8 1 1 - 8 D 1 KZN211L P6 19 8-2 P 1 P 3 0 3 3 3 9 3 -2 2 3 2 4 Kwazamokuhle HP - 2 L182 0 0 D Mvuthuluka S 9 1 N 0 L L 1 3 O 115 D -2 O D1113 N2 KZN212 D D D 9 1 1 1 Catalina Bay 1 Baphumlile CP 4 1 1 P2 1 7 7 9 8 !. D 6 5 10 Umswilili JP L 9 D 5 7 9 0 Sibongimfundo Velimemeze 2 4 3 6 Sojuba Mtumaseli S D 2 0 5 9 4 42 L 9 Mzingelwa SP 23 2 D 0 O O OL 1 O KZN213 L L 0 0 O L 2 3 2 L 1 2 Kwahlongwa P 7 3 Slavu LP 0 0 2 2 O 7 L02 7 3 32 R102 6 7 5 3 Buhlebethu S D45 7 P6 8-2 KZN214 Umzumbe JP St Conrad Incancala C Nkelamandla P 8 9 4 1 9 Maluxhakha P 9 D D KZN215 3 2 .! 50 - D2 Ngawa JS D 2 Hibberdene KwaManqguzuka 9 Woodgrange P N KZN216 !. -

Vol. 3 11 MAART 2009 No

:::::::::::;:;:;:::::: :::::::::: ::::::::::;:::::::: :::::::::::: : :::::::::::::::: ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::.:., :::::::: ::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::: ::: :::::::: :::::::::::::::::: ..... .... ... :::::::.::::: Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY-BUITENGEWONE KOERANT-IGAZETHI EYISIPESHELI (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As 'n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PI ETERMARITZBURG, 11 MARCH 2009 Vol. 3 11 MAART 2009 No. 240 11 kuNDASA 2009 2 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 11 March 2009 Page No. ADVERTISEMENT Road Carrier Permits, Pietermaritzburg......................................................................................................................... 3 11 March 2009 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 3 APPLICATION FOR PUBLIC ROAD CARRIER PERMITS OR OPERATING LICENCES Notice is hereby given in terms of section 37(I)(a) of the National Land Transport Transition Act, and section 52 (1) KZN Public Transport Act (Act 3 of2005) ofthe particulars in respect ofapplication for public road carrier permits and lor operating licences received by the KZN Public Transport Licensing Board, indicating: - (I) The appl ication number; (2) The name and identity number of the applicant; (3) The place where the applicant conducts his business or wishes to conduct his business, as well as his postal address; (4) The nature of the application, that is whether it is an application -

South Coast System

Infrastructure Master Plan 2020 2020/2021 – 2050/2051 Volume 4: South Coast System Infrastructure Development Division, Umgeni Water 310 Burger Street, Pietermaritzburg, 3201, Republic of South Africa P.O. Box 9, Pietermaritzburg, 3200, Republic of South Africa Tel: +27 (33) 341 1111 / Fax +27 (33) 341 1167 / Toll free: 0800 331 820 Think Water, Email: [email protected] / Web: www.umgeni.co.za think Umgeni Water. Improving Quality of Life and Enhancing Sustainable Economic Development. For further information, please contact: Planning Services Infrastructure Development Division Umgeni Water P.O.Box 9, Pietermaritzburg, 3200 KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa Tel: 033 341‐1522 Fax: 033 341‐1218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.umgeni.co.za PREFACE This Infrastructure Master Plan 2020 describes: Umgeni Water’s infrastructure plans for the financial period 2020/2021 – 2050/2051, and Infrastructure master plans for other areas outside of Umgeni Water’s Operating Area but within KwaZulu-Natal. It is a comprehensive technical report that provides information on current infrastructure and on future infrastructure development plans. This report replaces the last comprehensive Infrastructure Master Plan that was compiled in 2019 and which only pertained to the Umgeni Water Operational area. The report is divided into ten volumes as per the organogram below. Volume 1 includes the following sections and a description of each is provided below: Section 2 describes the most recent changes and trends within the primary environmental dictates that influence development plans within the province. Section 3 relates only to the Umgeni Water Operational Areas and provides a review of historic water sales against past projections, as well as Umgeni Water’s most recent water demand projections, compiled at the end of 2019. -

Kwazulu- Natal Municipalities: 2005

KWAZULU- NATAL District and Local AIDS Councils DISTRICT Or DAC/LAC Chairperson Municipal Manager Status of it AIDS Activities and Number of meetings held LOCAL COUNCIL or Mayor Council Challenges in the last 6 months KZ 211 Cllr B R Duma MM: Mr M H Zulu Orientation workshop planned Vulamehlo Tel: 039 974 0450 /2 Private Bag X 5509 Scottburgh - LAC launch and for the 7 and 8 August 2009 Municipality Fax: 039 974 0432 Dududu Mainroad PO Dududu revived Cell: 076 110 8436 Scottsburgh 4180 - Strategy plan [email protected] Tel: 039 974 0450 / 2 - Action plan Fax: 039 974 0432 Cell: 082 413 8639 e-mail:[email protected] KZ 212 Umdoni Cllr N H Gumede AMM: Mr D D Naidoo - LAC launched Municipality Tel: 039 976 1202 P O Box 19 Scottburgh 4180/ - Strategy plan Mr XS Luthuli Fax: 039 976 2194 Cnr Airth &Williamson Street Cell: 082 922 2500 Scottburgh xolanil@umdoni- Tel: 039 976 1202 online.co.za Fax: 039 976 2194 Tel: 039 974 1061 [email protected] Fax: 039 974 4148 KZ213Umzumbe Cllr M A Lushaba MM: Mr M Mbhele P O Box 561 - LAC launch Municipality Tel: 039 684 9181 Hibberdene 4220 - Wards AIDS Mr NC Khomo Fax: 039 684 9168 Kwahlongwa Community Hall committees Cell: 071604 0402 Cell: 083 956 6828 KwaHlongwa Area ,Umzumbe established Fax: 039 972 5599 Tel: 039 684 9180/1 - Developing strategy e-mail: Fax: 039 684 9168 / 9960 plan [email protected] Cell: 083 411 0334 .za [email protected] KZ 214 Cllr M W Memela MM: Mr S Mbhele - Interim LAC Financial constraint uMuziwabantu Tel: 039 433 1205 P O Box 23 Harding 4660 -

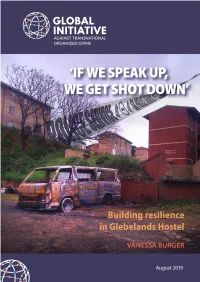

Building Resilience in Glebelands Hostel

‘IF WE SPEAK UP, WE GET SHOT DOWN’ Building resilience in Glebelands Hostel Vanessa Burger August 2019 Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the Global Initiative, members of the media, organizations and individuals for their concern, help, support, advice and encouragement provided over the years – either wittingly or unwittingly. This report was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Sector Programme Peace and Security, Disaster Risk Management of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect those of the BMZ or the GIZ. All photos: Vanessa Burger, except where specified. © 2019 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Contents Abbreviations and acronyms ..........................................................................................................................................................iv Glebelands Hostel: Ground zero for political killings ...........................................................................1 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................................................................3 -

Provincial Road Network Provincial Road Network All Other Roads P, Concrete L, Blacktop G, Blacktop On-Line Roads .! Major !C Clinics

D O 1 P u 3 4 L 3 7 l 3 0 0 4 4 u Manyonga Lp Maria 24 1 Khathi H 6 Luthuli H 9 !. k 9 5 1 2 OL Kwanguza P Ntabalukhozi H 6 3 02 4 m D 6 2 3 34 2 i Trost Hp 1 2 3 z 0 Stoney 4 L L D Ndunge P 0 Mnamfu 1 5 2 M L Nyangwini L Hill P 3 Kwaphuza Sp O 5 Mnafu Jp 0 7 O L O 0 1 Provincial L0 Umsinsini Jp 153 P 3 Dibi Jp Nkukhu Lp Bonguzwane S 2 350 132 D 3 0 Clinic 4 1 Mandlendoda P 4 1 L St Williams P 4 34 1 0 3 2 5 0 2 5 P73 D219 2 L 2 O 1 Bongucele Js Bonginduna Cp Fingqindlela S 8 4 O 9 L 0 0 6 4 2 2105 3 4 L 3 D D 35 4 Lucas 3 O 5 O 2 L 0 9 2 9 i 3 53 0 Maria Memorial P 35 9 2 D 9 L D y 0 a 1 O Trost Jp Mabuthela H 3 D m 6 i 152 3 51 3 z 33 3 L0 D 1 O 9 M 0 53 8 L 1 D L O 4 8 Makhoso Cp 92 9 0 2502 D 5 2 L 9 P 1 3 4 6 L 9 3 8 7 4 3 3 1 2 7 - 6 5 6 2 2 O 2 1 L - 0 Mabiya Ss OL03353 3 4 5 2 9 L L Zijubezulu P Bangibizo Jp 3 D 0 Kwamqadi P 3 2 0 2 3 N O 10 OL03362 0 L 0 2 139 L Esiwoyeni P 49 L L 3 9 4 , D O O 3 5 155 Sinokubonga Sp 5 8 Ebumbeni Jp 4 5 3 KZN211St Faiths P D Kwafica H O 3 291 0 Hlwathika P 8 Bhekizizwe Jp L O L Siyakhona P St. -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

Heritage Impact Assessment of Port Edward / Harding Power Lines, Kwazulu-Natal and Eastern Cape Provinces, South Africa

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF PORT EDWARD / HARDING POWER LINES, KWAZULU-NATAL AND EASTERN CAPE PROVINCES, SOUTH AFRICA Assessment and report by For SiVEST Telephone Richard Kinvig 033 345 2702; Fax 033 345 2672 Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 PIETERMARITZBURG South Africa Telephone 033 326 1136 Facsimile 086 672 8557 082 655 9077 / 072 725 1763 [email protected] 21 August 2008 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF PORT EDWARD / HARDING POWER LINES, KWAZULU-NATAL AND EASTERN CAPE Management summary eThembeni Cultural Heritage was appointed by SiVEST to undertake a heritage impact assessment of three proposed power line routes between Port Edward and Harding. Since the proposed servitudes are located in both KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape, both the KwaZulu-Natal Heritage Act No 10 of 1997 and the Heritage Resources Management Act No 25 of 1999 apply to this project. Two eThembeni staff members inspected the area on 30 and 31 July and 1 August 2008 and completed a controlled-exclusive surface survey, as well as a database and literature search. The purpose of this heritage impact assessment has been to identify two preferred power line servitudes between Port Edward and Harding. Of the three route alternatives that we examined, none is preferable; i.e. all three are equally (un)likely to affect heritage resources. We recommend that a heritage practitioner return to the study area to survey both final servitudes, including an examination of exact tower placements and all construction infrastructure (contractor’s camp, access roads, etc.) before the start of any construction activities, to ensure that no heritage resources are affected. -

Provincial Road Network Umzumbe Local Municipality (KZN213)

N P L Mk h 7 Dumayo Lp 70 Siphephile S 2 om D978 978 la 207 7 D9 5 az D Enkanini P 5 i Isulethu P v 2 in Amandlalathi P 2 Emazizini Jp i D Nkweletsheni P 3 - 1 9 M 028 5 Zamokuhle k L Norman 6 oma O P 7 zi Store Emazizini Trading !. e D D2386 O J.P. School n 9 Store L a 6 Mkhunya 4 8 0 R612 8 7 6 2 R w 7 7 7 0 P g 9 23 2 7 1 8 -1 56 n 0 7 IJ 2 Shukumisa Sp D L i u 0 n t O L i O v M Emhlonhlweni Cp la Mntungwana Tshenkombo Jp h N 9 Sivelile Js Qiko H N hl 29 39 Clinic Mtholi Cp 8 174 a 7 v D D Ixopo ini 7 9 2 64 M2 Provincial Mob. Base 0 Mazongo P L Ixopo Health Centre 3 Ixopo Ixopo M3 1 O 6 0 9 237 5 D Village IxoPprovincial G 7 77 D .! P 7 1 Int Mob. Base 2 P 7 Ixopo M1 Provincial Mob. Base 1 0 0 7 9 L 1 3 7 O 2 Ixopo P 9 197 55 0 6 09 L D 4 238 1 O D7 Sizathina Js D1 9 0 63 Little 8 7 22 6 2 Kwamiso Cp Sangqula Cp 2776 Flower S D 5 KZN211 OL0 Ixopo H 5 _ D 2 W 171 D O Zasengwa Jp 5 R 8 194 P 7 186 2 Christ The 0 Babongile Sp O L O O O L King Provintial L L 02 Nhlayenza Jp 0 0 OL 7 2 27 027 8 Hospital 7 8 84 3 180 L 8 6 1 7 L 1 L 0 8 1 Siyathokoza Lp 1 3 67 8 1 2 3 8 0 L 4 0 Sanywana 3 28 0 8 L0 High 3 O 0 25 O 21 1 Sithuthukile S Thandokwethu P KZN212 L D O 0 196 L Indunduma Cp 9 2 0 52 D 7 2 P Sangcwaba 2 8 5 7 3 8 8 209 7 70 Clinic 1 7 8 3 0 Stainton L97 2 02 2 0 OL 5 0 !. -

Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIE ISIFUNDAZWE SAKWAZULU-NATALI Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As ’n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG Vol. 10 20 OCTOBER 2016 No. 1742 20 OKTOBER 2016 20 KUMFUMFU 2016 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1994-4558 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 01742 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771994 455008 2 No. 1742 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 20 OCTOBER 2016 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 20 OKTOBER 2016 No. 1742 3 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. CONTENTS Gazette Page No. No. PROVINCIAL NOTICES • PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWINGS 174 KwaZulu-Natal Land Administration and Immovable Asset Management Act (2/2014): Notice in terms of section 9(4)(a) of the Act ................................................................................................................................................. 1742 11 174 KwaZulu-Natal Wet op Grondadministrasie en die Bestuur van Onroerende Bates (2/2014): Kennisgewing ingevolge artikel 9(4)(a) van die Wet .................................................................................................................. 1742 12 175 KwaZulu-Natal Gaming and Betting Act (8/2010): Notice of applications received in terms of section 44 ......... 1742 14 175 KwaZulu-Natal Dobbelary en Weddery (8/2010): Kennisgewing van aansoeke in terme van artikel 44 van die Wet .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Taxonomic Revision of South African Memecylon (Melastomataceae–Olisbeoideae), Including Three New Species

Phytotaxa 418 (3): 237–257 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.418.3.1 Taxonomic revision of South African Memecylon (Melastomataceae—Olisbeoideae), including three new species ROBERT DOUGLAS STONE1, IMERCIA GRACIOUS MONA2, DAVID STYLES3, JOHN BURROWS4 & SYD RAMDHANI5 1School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg 3209, South Africa; [email protected] 2,5School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa; [email protected], [email protected] 327A Regina Road, Umbilo, Durban 4001, South Africa; [email protected] 4Buffelskloof Nature Reserve Herbarium, Lydenburg, South Africa; [email protected] Abstract Earlier works recognised two South African species Memecylon bachmannii and M. natalense within M. sect. Buxifolia, but recent molecular analyses have revealed that M. natalense as previously circumscribed is not monophyletic and includes several geographically outlying populations warranting treatment as distinct taxa. In this revision we recognise five endemic South African species of which M. bachmannii and M. natalense are both maintained but with narrower circumscriptions, and M. kosiense, M. soutpansbergense and M. australissimum are newly described. Memecylon kosiense is localised in north-eastern KwaZulu-Natal (Maputaland) and is closely related to M. incisilobum of southern Mozambique. Memecylon soutpansbergense, from Limpopo Province, was previously confused with M. natalense but is clearly distinguished on vegetative characters. Memecylon australissimum occurs in the Eastern Cape (Hluleka and Dwesa-Cwebe nature reserves) and has relatively small leaves like those of M. natalense, but the floral bracteoles are persistent and the fruit is ovoid as in M.