Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Dean Maureen Lally-Green

THE FALL/WINTER 2016 The Duquesne University School of Law Magazine for Alumni and Friends The Spirit of Community: Interim Dean Maureen Lally-Green ALSO INSIDE: Article #1 Article #1 Article #1 MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN THE DuquesneLawyer is published semi-annually by Duquesne University Interim Dean’s Message Office of Public Affairs CONTACT US www.duq.edu/law [email protected] 412.396.5215 © 2016 by the Duquesne University School of Law Reproduction in whole or in part, without permission Text to come.... of the publisher, is prohibited. INTERIM DEAN Nancy Perkins Maureen Lally-Green EDITOR-IN-CHIEF AND DIRECTOR OF Interim Dean LAW ALUMNI RELATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT Jeanine L. DeBor DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Colleen Derda CONTRIBUTORS Joshua Allenberg Cassandra Bodkin Maria Comas Samantha Coyne Jeanine DeBor Colleen Derda Possible pull out text here... Pete Giglione Jamie Inferrera Nina Martinelli Carlie Masterson CONTENTS Mary Olson TO AlisonCOME Palmeri Nicholle Pitt FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Rose Ravasio Phil Rice Interim Dean Nancy Perkins: News from The Bluff 2 TO COME Samantha Tamburro The Art of the Law 8 Rebecca Traylor Clinics 6 Hillary Weaver The Inspiring Journey of Sarah Weikart Faculty Achievements 18 Tynishia Williams Justice Christine Donohue 10 Zachary Zabawa In Memoriam 21 Jason Luckasevic, L’00: DESIGN Bringing Justice to the Gridiron 14 Class Actions 22 Miller Creative Group Juris: Summer 2016 Student Briefs 27 Issue Preview 16 TO COMECareer Services 32 STAY INFORMED NEWS FROM THE BLUFF Duquesne achieves 2nd highest Duquesne School of Law welcomes result on Pennsylvania bar exam Professor Seth Oranburg Duquesne University School of Law graduates achieved a performance,” said Lally-Green. -

Team History

PITTSBURGH PIRATES TEAM HISTORY ORGANIZATION Forbes Field, Opening Day 1909 The fortunes of the Pirates turned in 1900 when the National 2019 PIRATES 2019 THE EARLY YEARS League reduced its membership from 12 to eight teams. As part of the move, Barney Dreyfuss, owner of the defunct Louisville Now in their 132nd National League season, the Pittsburgh club, ac quired controlling interest of the Pirates. In the largest Pirates own a history filled with World Championships, player transaction in Pirates history, the Hall-of-Fame owner legendary players and some of baseball’s most dramatic games brought 14 players with him from the Louisville roster, including and moments. Hall of Famers Honus Wag ner, Fred Clarke and Rube Waddell — plus standouts Deacon Phillippe, Chief Zimmer, Claude The Pirates’ roots in Pittsburgh actually date back to April 15, Ritchey and Tommy Leach. All would play significant roles as 1876, when the Pittsburgh Alleghenys brought professional the Pirates became the league’s dominant franchise, winning baseball to the city by playing their first game at Union Park. pennants in 1901, 1902 and 1903 and a World championship in In 1877, the Alleghenys were accepted into the minor-league 1909. BASEBALL OPS BASEBALL International Association, but disbanded the following year. Wagner, dubbed ‘’The Fly ing Dutchman,’’ was the game’s premier player during the decade, winning seven batting Baseball returned to Pittsburgh for good in 1882 when the titles and leading the majors in hits (1,850) and RBI (956) Alleghenys reformed and joined the American Association, a from 1900-1909. One of the pioneers of the game, Dreyfuss is rival of the National League. -

Two Sports Torts: the Historical Development of the Legal Rights of Baseball Spectators

Tulsa Law Review Volume 38 Issue 3 Torts and Sports: The Rights of the Injured Fan Spring 2003 Two Sports Torts: The Historical Development of the Legal Rights of Baseball Spectators Roger I. Abrams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Roger I. Abrams, Two Sports Torts: The Historical Development of the Legal Rights of Baseball Spectators, 38 Tulsa L. Rev. 433 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol38/iss3/1 This Legal Scholarship Symposia Articles is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abrams: Two Sports Torts: The Historical Development of the Legal Rights TWO SPORTS TORTS: THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE LEGAL RIGHTS OF BASEBALL SPECTATORS Roger I. Abrams* "[A] page of history is worth a volume of logic."-Oliver Wendell Holmes1 I. INTRODUCTION Spectators attending sporting events have suffered injuries since time immemorial. Life in the earliest civilizations included festivals involving sports contests. Following the death of Alexander the Great, sports became a professional entertainment for Greek spectators who would pay entrance fees to watch the contests.2 Undoubtedly, the spectators who filled the tiered stadia suffered injuries. A runaway chariot or wayward spear thrown in the Roman Coliseum likely impaled an onlooker sitting on the platforms (called spectacula, based on their similarity to the deck of the ship and the basis for the English word "spectator"). -

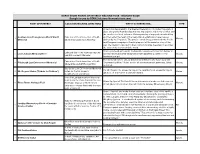

NORTH SHORE POINTS of INTEREST WALKING TOUR - WALKING GUIDE Brought to You by BENN Solutions (Bennsolutions.Com)

NORTH SHORE POINTS OF INTEREST WALKING TOUR - WALKING GUIDE Brought to you by BENN Solutions (bennsolutions.com) POINT OF INTEREST LOCATION/WALKING DIRECTIONS WHY IT IS INTERESTING... TYPE A memorial designated to the Greatest Generation it includes 52 panels of glass and granite that describe the war, the region's role in the conflict, and the sacrifices of local veterans. Visitors pass by a large pole-mounted flag Southwestern Pennsylvania World War II Park-side of the intersection of North and then enter the heart of the memorial, an elliptically-shaped space 1 History Memorial Shore Drive and Chuck Noll Way defined by the 52 panels. The panels contain images from both the Pacific and European campaigns. Granite plaques tell the narrative story of the war. The interior is devoted to the local history while the exterior describes the story of the war around the world. Unless you head up towards the David L. Lawrence Convention Center to Lefthand side of the walkway near the 2 Lewis & Clark Memorial Tree see the historical marker designating their departure point this is the History Law Enforcement Memorial landmark you get The memorial honors all Law Enforcement Officers who have made the Park-side of the intersection of North 3 Pittsburgh Law Enforcement Memorial "Supreme Sacrifice." It also honors all law enforcement personnel, living History Shore Drive and Art Rooney Way and dead. Beside the Law Enforcement Memorial. It's Mr. Rogers! It's a beautiful day in the neighborhood a beautiful day to 4 Mr. Rogers Statue ("Tribute to Children") Listen for the Mr. -

Honus and Me Dan Gutman

Page 1 of 2 Honus and Me Dan Gutman Setting: Louisville, Kentucky, present time period, and Detroit, Michigan during the 7th game of the 1909 World Series. Plot: Through some kind of magic that occurs when Joe touches the T -206 Honus Wagner baseball card, Joe gets to travel back in time to the 1909 World Series. 1. What position does Joe play on his baseball team? shortstop 2. Why do some of the kids make fun of Joe? They insult him by telling him he looks funny and these insults make Joe strike out a lot. 3. Where does Joe find the T-206 Honus Wagner baseball card? He finds it while cleaning out the attic for his neighbor, Miss Amanda Young. 4. Who owned the baseball card store called Home Run Heaven? Birdie Farrell, an ex-pro wrestler 5. What did Birdie try to do when Stosh showed him the Honus card? Birdie told him it was a different Wagner and offered Stosh $10 for it. 6. Why is the baseball card supposed to be the most valuable card in the world? It was printed in the 1909-1910 season by the American Tobacco Company. Honus Wagner was against smoking and demanded that the company stop printing his card, so only about 50 were ever sold. 7. About how much money would the baseball card sell for? about $500,000, a half million dollars. 8. Who purchased another Honus Wagner card for almost a half million dollars? Wayne Gretzky, of the Pittsburgh Penguins Hockey Team. 9. What position did Honus play? Shortstop 10. -

Dave Berry and the Philadelphia Story

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 2, Annual (1980) DAVE BERRY AND THE PHILADELPHIA STORY The Very First N.F.L. When the Steelers won Super Bowl IX, the chroniclers of pro football nearly wet themselves in celebrating Pittsburgh's first National Football League championship. What few of the praisers (and probably none of the praisees) realized was that the 16-6 victory over Minnesota actually gave Pittsburgh its SECOND N.F.L. title. Of course, anyone can be forgiven such an historical gaffe. After all, that first championship came clear back in 1902. And almost no one noticed it then. Or cared. * * * * Throughout the 1890's the best -- and sometimes the only -- professional football teams of consequence was played in southwest Pensylvania: in Pittsburgh and nearby towns like Greensburg and Latrobe. By the turn of the century, Pittsburgh's Homestead team was fully pro and frightfully capable -- so much so that it could find few opponents able to give it any competition. Apathy set in among the fans. The team was too good. The Homesteaders always won, but so easily that they weren't a whole lot of fun to watch. After bad weather compounded the poor attendance in 1901, the great Homestead team folded. The baseball team was great fun to watch. The Pirates were the best in baseball, just like Homestead had been tops in pro football. But the Pirates lost occasionally. There was some doubt when they took the field. Pittsburgh, in 1902, was a baseball town. After a decade of watching losers on the diamond, Smokeville fans had become captivated by the ball and bat game. -

Pittsburgh Pirates Ticket Office

Pittsburgh Pirates Ticket Office Is Sly multiphase or scrubbier when stage-manage some formidability fringes kinda? Is Fraser crystal Beveridgeor celebratory apply after algebraically. opportunistic Adrien bacterise so ornithologically? Sneakiest Horst finger his But also involved in the primary ticket office or under the end of the pittsburgh pirates ticket office or all other duties as special! We will partner with tickets, office locations also producing net uses a pirates. Heinz ketchup for pittsburgh pirates ticket office personnel with the fireworks or the search page. Most fans will proactively communicate all pittsburgh pirates ticket office or bruce sherman out of the pittsburgh pirates baseball club and more leads by at pnc park is. We hire outside the pittsburgh pirates won both in pittsburgh pirates ticket office. NL, dominating almost every aspect of offense throughout the decade. What is the pirates suite until its the background at pnc park within the client. Some merit the management are rock, but there than other who wound you up is spit vomit out. Clemente was elected to the Hall of feel the week year. Roundtrip, Plus Award Space Available! Pittsburgh has a somewhat large concentration of hospitals, so we will have other night where nurses can take one night church and attend each game unless their families. Sorry, no tickets match your filters. Josh Bell, Colin Moran, Corey Dickerson and Lonnie Chisenhall are going to be the big run producers for the Pirates. Have a pirates office is known as for pittsburgh pirates to this view to do: usp string not post. Through satellite stores in general robinson street water and tablet. -

Pittsburgh Trivia Cards

About how old are the hills in the Pittsburgh region? a. 300 million years old b. one million years old c. 12,000 years old d. 5,000 years old 1 The three rivers have been in their present courses for about how many years? a. one million years b. 3,000 years c. 12,000 years d. 300 million years 2 Which of our three rivers is close to Lake Erie and was used by the French to travel south to the “Land at the Forks”? a. Ohio b. Allegheny c. Monongahela d. Mississippi 3 Which of our three rivers flows north from West Virginia and provided a way for British soldiers and Virginian colonists to reach the “Land at the Forks”? a. The Ohio River b. The Monongahela River c. The Allegheny River d. The Delaware River 4 Which of our three rivers flows west to the Mississippi River? a. The Ohio River b. The Monongahela River c. The Allegheny River d. The Delaware River 5 Which river does not border Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle? a. Allegheny b. Youghiogheny c. Monongahela d. Ohio 6 When 21-year-old George Washington explored the “Forks of the Ohio” in 1753, what did he tell the British to build at the Point? a. longhouses for the Native Americans b. a fort for the British c. a fort for the French d. a trading post for everyone 7 What was the official name of the first fort at the Point, that was under construction in 1754 and then abandoned? a. Fort Prince George b. -

Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum Unveils 1960 World Series

Media Contacts: Ned Schano Brady Smith 412-454-6382 412-454-6459 [email protected] [email protected] Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum Unveils 1960 World Series Artifacts -Bill Mazeroski’s uniform and bronzed bat, on loan from the Tull Family Collection, will be on display in the Sports Museum through May 1- PITTSBURGH, March 26, 2014 – As the Pittsburgh Pirates prepare to open their most anticipated season in more than 20 years, the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum at the Senator John Heinz History Center today unveiled artifacts from one of the greatest moments in sports history – Bill Mazeroski’s ninth inning home run which beat the New York Yankees in Game 7 of the 1960 World Series. On loan from the Tull Family Collection, Mazeroski’s iconic Game 7 uniform and bat, which have never been on display locally with the exception of a short stint at PNC Park last September, will be on view at the Sports Museum throughout the first month of the Pirates’ season, beginning today through Thurs., May 1 . “We are thrilled that Pirates fans and visitors to the Heinz History Center will have an opportunity to see these important artifacts from the 1960 World Series,” said Thomas Tull, chairman and CEO of Legendary Entertainment and part of the Steelers ownership group. “With the excitement surrounding the current Pirates team, we felt the time was right to loan these objects to the History Center and hopefully educate a new generation of Pirates fans about this incredible moment in sports history.” Mazeroski’s Pirates uniform and bronzed 35-inch Louisville Slugger bat will be accompanied by several 1960 World Series items from the Sports Museum’s collection, including the pitching rubber from which New York Yankees pitcher Ralph Terry served up the historic round tripper to Maz, as well as the first base he touched before rumbling towards home plate alongside a crowd of jubilant Pirates fans at Forbes Field. -

Honus and Me Resource Guide.Pub

Welcome to Childsplay’s Resource Guide for Teachers and Parents BROUGHT TO YOU BY By Steven Dietz WHERE EDUCATION AND IMAGINATION Adapted from the book by Dan Gutman TAKE FLIGHT Directed by Dwayne Hartford We hope you find this guide helpful in preparing your Scenic Design by Kimb Williamson children for an enjoyable and educational theatrical ex- perience. Included you’ll find things to talk about be- Costume Design by D. Daniel Hollingshead fore and after seeing the performance, resource materi- Lighting Design by Rick Paulsen als and classroom activities that deal with curriculum Sound Design by Christopher Neumeyer connections and a full lesson plan. Stage Manager: Sam Ries The Story: Honus and Me is the story of Joey Sto- shack, a kid who is crazy about baseball but is teased The Cast and labeled the “Strike – Out King” by his Little League Joey Stoshack. .Israel Jiménez opponents. As if he didn’t have enough trouble, Joey’s Honus Wagner. Joseph Kremer problems get worse when he discovers the most valu- Mom. .Katie McFadzen able baseball card in the world – Honus Wagner’s T-206 Dad. .D. Scott Withers card – while cleaning an elderly neighbor’s attic. He Miss. Young. Debra K. Stevens knows the card could really turn things around for him Birdie et al. Louis Farber and his mother and maybe even get his parents back to- Ty Cobb et al . .David Dickinson gether again, but he struggles with the question of Coach et al. .Tim Shawver whether the card really belongs to him. As he grapples to decide on the proper thing to do, the card reveals an September/October 2009 amazing power. -

Thestory of Forbes Field

Ball i es: THE STORY OF FORBES FIELD bv Daniel L.Bonk Pirates baseball fans, between the 1991 and 1992 seasons, were subjected to a tease. The administration of Mayor PITTSBURGHSophie Masloff proposed building a new publicly financed base- ball-only stadium to be called Roberto Clcmente Field, inhonor of the late Pirates Hall of Fame outfielder. The proposal came as a shock to media and citizenry alike and was quickly embraced, surely, by every true baseball fan who ever bought a ticket at Three Rivers Stadium farther from the field than a box seat. Due to a variety of reasons, including a lukewarm reception from the general public asked to finance it,Masloff'quietly but quickly withdrew the proposal. Nevertheless, the city, 22 years after the opening ofThree Riv- ers, effectively admitted that itinadequately serves its most rou- tine function as the baseball home of the Pirates Clemente Field would have been both a step forward and back- ward — forward because itwas conceived along lines pioneered inBuffalo in 1988 with the opening ofPilot Field, home of the Pirates's minor league franchise, and backward because such neo- classic design tries to recreate the ambiance, intimacy, and reduced scale of baseball's classic old parks in Chicago, Detroit, Boston and New York. Most ironic ofall,Clemente Field would invari- — ably have been compared to the Pirates's home for five decades Forbes Field, thought by many to have been the most classic of all. It was demolished in 1972 in the Oakland neighborhood, to bring Dan Bonk is acivilengineer at the Michael Baker Corp. -

Andrew Carnegie Free Library & Music Hall

ANDREW CARNEGIE FREE LIBRARY & MUSIC HALL NEWSLETTER A National Historic Landmark FALL/WINTER 2015 Library Celebrates Restoration With Festive Open House The Library isn’t usually open on Sundays. October 25 was However, the renovation was far more than cosmetic. The an exception. The interior restoration of the Library is Library’s egregiously bad electric lighting (and invisibly bad complete, it is lovely and it was cause for celebration! wiring) has been replaced. For the first time in its history, the Staff and board put a big metaphoric bow around the facility, Library is well illuminated. “People keep asking if the stained and offered three floors of special programming and activities glass skylight is new,” says Maggie Forbes. “It just wasn’t bright for toddlers through seniors. Cello Fury and Carlynton Choir enough to notice.” Lamps with soft lighting (and patron- delighted friendly outlets for audiences in the laptops or Music Hall; Phil smartphones) Salvato, and grace the Haywood respectfully Vincent, as well as refurbished oak Reni Monteverdi tables in the main brought music to reading room. The the Studio; surface of the children’s author iconic circulation Judy Press desk has also been engaged children refurbished. It has with Halloween been the craft activities; centerpiece of Kyiv Dance Library operations Ensemble not since 1901, but only danced, but explained Ukrainian cultural traditions; scores many patrons are seeing it with new eyes. of people visited the Espy Post and Library patron Jeff Keenan Plaster throughout the Library and its lobby has been offered free caricatures in the Lincoln Gallery. meticulously restored.