The Theory and Practice of Integrating Invertible Counterpoint Into Classical Theme-Types Peter Franck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Third Period of César Franck Author(S): Sydney Grew Source: the Musical Times, Vol

The Third Period of César Franck Author(s): Sydney Grew Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 60, No. 919 (Sep. 1, 1919), pp. 462-464 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3701958 Accessed: 25-03-2015 19:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 25 Mar 2015 19:50:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 462 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-SEPTEMBER I, 1919. He is content to spend days on a single passage I wasnot sorrowful. (Boosey.) The Cost. 2. The so that he gives it the one ultimate formwhich (I. Blind; Cost.) (WinthropRogers.) afterwards to be the inevitable form it The Soldier. (WinthropRogers.) proves Blowout, you bugles. (WinthropRogers.) should take. Yet this constant preoccupation The Heart'sDesire. (WinthropRogers.) with precision in detail has nowhere resulted in Earth's Call. (Rhapsodyfor voice and pianoforte.) laboured writing. His harmonic texture may be (WinthropRogers.) or suave or SpringSorrow. -

César Franck's Violin Sonata in a Major

Honors Program Honors Program Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 C´esarFranck's Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer's Influence on the Violin Repertory Clara Fuhrman University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/honors program theses/21 César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer’s Influence on the Violin Repertory By Clara Fuhrman Maria Sampen, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements as a Coolidge Otis Chapman Scholar. University of Puget Sound, Honors Program Tacoma, Washington April 18, 2016 Fuhrman !2 Introduction and Presentation of My Argument My story of how I became inclined to write a thesis on Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major is both unique and essential to describe before I begin the bulk of my writing. After seeing the famously virtuosic violinist Augustin Hadelich and pianist Joyce Yang give an extremely emotional and perfected performance of Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major at the Aspen Music Festival and School this past summer, I became addicted to the piece and listened to it every day for the rest of my time in Aspen. I always chose to listen to the same recording of Franck’s Violin Sonata by violinist Joshua Bell and pianist Jeremy Denk, in my opinion the highlight of their album entitled French Impressions, released in 2012. After about a month of listening to the same recording, I eventually became accustomed to every detail of their playing, and because I had just started learning the Sonata myself, attempted to emulate what I could remember from the recording. -

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet and ODU Cello Choir

Program String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Alexander Borodin 1. Allegro Moderato (1833-1887) 3. Notturno - Andante The ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet Jordan Goodmurphy, Violin Emily Pollard, Violin F. Ludwig Diehn School of Music Joshua Clarke, Viola Michael Russo, Cello Trio in C Major, Op. 87 for Three Cellos L.V. Beethoven 3. Minuetto-Allegro molto scherzo. Trio. (1770-1827) trans. A.C. Prell ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet ODU Cello Choir Requiem, Op. 66 for Three Cellos and Piano David Popper Andante Sostenuto (1843-1913) Leslie J. Frittelli, director Carter Campbell, piano Sonata No. 1 in A Major for Three Cellos Arcangelo Corelli 1. Grave (1653-1713) 2. Allegro arr. Erinn Renyer 3. Adagio 4. Allegro ODU Cello Choir Carter Campbell Diehn Center for the Performing Arts Trinity Green Chandler Recital Hall Joshua Kahn Lexi McGinn Avery Suhay Aleta Tomas Lacey Wilson Friday, November 22, 2019 7:30 pm Program String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Alexander Borodin 1. Allegro Moderato (1833-1887) 3. Notturno - Andante The ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet Jordan Goodmurphy, Violin Emily Pollard, Violin F. Ludwig Diehn School of Music Joshua Clarke, Viola Michael Russo, Cello Trio in C Major, Op. 87 for Three Cellos L.V. Beethoven 3. Minuetto-Allegro molto scherzo. Trio. (1770-1827) trans. A.C. Prell ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet ODU Cello Choir Requiem, Op. 66 for Three Cellos and Piano David Popper Andante Sostenuto (1843-1913) Leslie J. Frittelli, director Carter Campbell, piano Sonata No. 1 in A Major for Three Cellos Arcangelo Corelli 1. Grave (1653-1713) 2. -

Rachael Dobosz Senior Recital

Thursday, May 11, 2017 • 9:00 p.m Rachael Dobosz Senior Recital DePaul Recital Hall 804 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Thursday, May 11, 2017 • 9:00 p.m. DePaul Recital Hall Rachael Dobosz, flute Senior Recital Beilin Han, piano Sofie Yang, violin Caleb Henry, viola Philip Lee, cello PROGRAM César Franck (1822-1890) Sonata for Flute and Piano Allegretto ben Moderato Allegro Ben Moderato: Recitativo- Fantasia Allegretto poco mosso Beilin Han, piano Lowell Liebermann (B. 1961) Sonata for Flute and Piano Op.23 Lento Presto Beilin Han, piano Intermission John La Montaine (1920-2013) Sonata for Piccolo and Piano Op.61 With driving force, not fast Sorrowing Searching Playful Beilin Han, piano Rachael Dobosz • May 11, 2017 Program Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Quartet in C Major, KV 285b Allegro Andantino, Theme and Variations Sofie Yang, violin Caleb Henry, viola Philip Lee, cello Rachael Dobosz is from the studio of Alyce Johnson. This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the degree Bachelor of Music. As a courtesy to those around you, please silence all cell phones and other electronic devices. Flash photography is not permitted. Thank you. Rachael Dobosz • May 11, 2017 Program notes PROGRAM NOTES César Franck (1822-1890) Sonata for Flute and Piano Duration: 30 minutes César Franck was a well known organist in Paris who taught at the Paris Conservatory and was appointed to the organist position at the Basilica of Sainte-Clotilde. From a young age, Franck showed promise as a great composer and was enrolled in the Paris Conservatory by his father where he studied with Anton Reicha. -

Barbara Barry Invisible Cities and Imaginary Landscapes 'Quasi Una Fantasia': on Beethoven's Op.131

barbara barry Invisible cities and imaginary landscapes ‘quasi una fantasia’: on Beethoven’s op.131 I will put together, piece by piece, the perfect city, made of fragments mixed with the rest, of instants separated by intervals, of signals one sends out, not knowing who receives them. Italo Calvino.1 n his famous essay The hedgehog and the fox, Isaiah Berlin discusses a fragment from the ancient Greek poet Archilochus and interprets it in Ia rather unusual way.2 According to Archilochus, ‘The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.’ Clearly, the hedgehog’s 1. Italo Calvino: Invisible one big thing is the defence tactic of curling up in a ball, spikes out, to cities, trans. William Weaver repel an invader, although no one cares to spell out what the fox knows. (London, 1997), p.147. Nietzsche discusses how it Commentators in the past have taken Archilochus’s rather cryptic remark as is essential to forget as well an implicit criticism of fox-like behaviour, where people flit from one interest as to remember in order to retain one’s humanity. to another rather than focusing on a central plan of action. Hedgehogs don’t He says: ‘Imagine the come off any better in the assessment stakes as they put all their eggs in one most extreme example, the most extreme example of basket instead of having at least one version of Plan B. a human being who does Berlin, though, has a different, and more positive view of both hedgehogs not possess the power and foxes. -

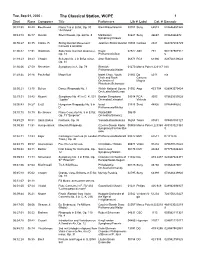

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Sep 01, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 40:40 Beethoven Piano Trio in B flat, Op. 97 Stern/Rose/Istomin 03707 Sony 64513 074646451328 "Archduke" 00:43:1006:17 Dvorak Silent Woods, Op. 68 No. 5 Ma/Boston 02621 Sony 46687 07464466872 Symphony/Ozawa 00:50:27 08:35 Clarke, R. String Quartet Movement: Julstrom String Quartet 10806 Centaur 2847 044747284729 Comodo e amabile 01:00:3217:51 Goldmark Sakuntala (Concert Overture), Royal 02522 ASV 791 501197507912 Op. 13 Philharmonic/Butt 5 01:19:23 09:43 Chopin Scherzo No. 2 in B flat minor, Artur Rubinstein 06971 RCA 61396 828766139624 Op. 31 01:30:0627:59 Reinecke Symphony in A, Op. 79 Rhenish 01270 Marco Polo 8.223117 N/A Philharmonic/Walter 01:59:35 04:46 Pachelbel Magnificat Motet Choir, Youth 01900 Da 5011 n/a Choir and Bach Camera Orchestra of Magna Pforzheim/Schweizer 02:05:21 13:10 Delius Dance Rhapsody No. 1 Welsh National Opera 01052 Argo 433 704 028943370424 Orchestra/MacKerras 02:19:3139:42 Mozart Symphony No. 41 in C, K. 551 Boston Symphony 09514 RCA 9305 078635930528 "Jupiter" Orchestra/Leinsdorf VIctrola 03:00:43 08:27 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 3 in Israel 01935 Sony 44926 07464449262 D Philharmonic/Mehta 03:10:1038:19 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Watts/EMF 09639 Op. 73 "Emperor" Orchestra/Schwarz 03:49:29 08:51 Saint-Saëns Fantasie, Op. 95 Yolanda Kondonassis 06268 Telarc 80581 089408058127 03:59:5031:51 Humperdinck Moorish Rhapsody Czecho-Slovak Radio 00509 Marco Polo 8.223369 489103023363 Symphony/Fischer-Die 0 skau 04:32:4114:34 Elgar Cockaigne Overture (In London Philharmonia/Barbirolli 09372 EMI 64511 D 141513 Town,) Op. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

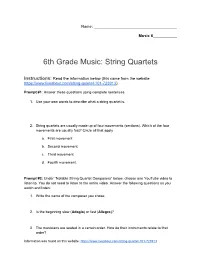

6Th Grade Music: String Quartets

Name: ______________________________________ Music 6___________ 6th Grade Music: String Quartets Instructions: Read the information below (this came from the website https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913). Prompt #1: Answer these questions using complete sentences. 1. Use your own words to describe what a string quartet is. 2. String quartets are usually made up of four movements (sections). Which of the four movements are usually fast? Circle all that apply a. First movement b. Second movement c. Third movement d. Fourth movement. Prompt #2: Under “Notable String Quartet Composers” below, choose one YouTube video to listen to. You do not need to listen to the entire video. Answer the following questions as you watch and listen: 1. Write the name of the composer you chose. 2. Is the beginning slow (Adagio) or fast (Allegro)? 3. The musicians are seated in a certain order. How do their instruments relate to that order? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 4. How do the musicians respond to each other while playing? Prompt #3: Under Modern String Quartet Music, find the Love Story quartet by Taylor Swift. Listen to it as you answer using complete sentences. 1. Which instrument is plucking at the beginning of the piece? (If you forgot, violins are the smallest instrument, violas are a little bigger, cellos are bigger and lean on the floor). 2. Reflect on how this version of Love Story is different from Taylor Swift’s original song. How would you describe the differences? What does this version communicate? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 String Quartet 101 All You Need to Know About the String Quartet The Jerusalem Quartet, a string quartet made of members (from left) Alexander Pavlovsky, Sergei Bresler, Kyril Zlontnikov and Ori Kam, perform Brahms’s String Quartet in A minor at the 92nd Street Y on Saturday night, October 25, 2014. -

Zorá String Quartet

ZORÁ STRING QUARTET OREGON ARTS WATCH: “They play like well-seasoned pros tuned into one another for years, but with so much exuberant passion they practically fall out of their seats. They are the future of chamber music. These musicians deserve all the prizes they continue to win. They are definitely on the rise with a bright future.” THE NEW YORK TIMES: “From the first phrase, played with rich sound and wistful beauty, I knew this would be an eloquent and probing performance. The Zorá played with melting sound and affecting impetuosity. In Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 9, an intense, fitful, brooding work, it was charming how these young musicians from Thailand, South Korea, China and Spain so strongly conveyed the very particular character of the hints of klezmer in the music.” OBERON’S GROVE (New York): How beautifully the Zora Quartet shaped this music. Today’s sublime performance was marked by technical assurance, clarity of individual voices, expressive finesse and opulent tone. THE CALGARY HERALD: “I cannot wait to hear the Zorá String Quartet again. Exquisitely well trained, supremely blended, and broadly intelligent in their playing, the Quartet makes you stop and listen very closely to their sound, fresh with sonic ideas in every phrase. What a great performance.” First Prize, 2015 Young Concert Artists International Auditions First Prize, 2015 Coleman National Chamber Music Competition Gold Medal, 2015 Fischoff Chamber Music Competition Sander Buchman Debut Prize • Friends of Music Concerts Prize (NY) Hayden’s Ferry Chamber Music Series Prize (AZ) • Paramount Theater Prize (VT) YOUNG CONCERT ARTISTS, INC. -

Lux String Quartet

LUX STRING QUARTET CURRICULUM CLASS NOTES® PRESENTED BY CLASSICAL MPR THESE MATERIALS ARE MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY THE MINNESOTA LEGACY AMENDMENT’S ARTS AND CULTURAL HERITAGE FUND. WELCOME TO CLASS NOTES CONCERTS We are so excited to bring live music into your school—thanks for hosting a concert. This curriculum includes: • Learning prompts for before, during, and after the concert experience • Standards-based, K-6 lesson plans based on themes and ideas from your Class Notes Concert Everything is designed to help you and your students get the most out of the experience. Please share your experience with us! Katie Condon, Education Specialist, Classical MPR, [email protected] BEFORE THE CONCERT LEARN WHAT YOU WILL HEAR During their Class Notes Concert, Lux String Quartet will play parts of these two pieces: • György Ligeti: String Quartet No. 1 “Métamorphoses nocturnes” • Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 9 in C major, Op. 59, Razumovsky, No. 3 MEET THE PERFORMERS When Erika Blanco isn’t playing or teaching the violin, she can usually be sighted running, writing, gardening, or giving unapologetic hugs to any and all of her three cats. Stephanie Skor is a violinist and her favorite thing to do besides playing violin is to swim in Lake Superior. CLASS NOTES® - CLASSICAL MPR 2 Kirsti Petraborg plays the viola. She also enjoys salsa dancing, boxing, and making her own clothes. Eric Graf is a professional cellist. He enjoys reading, traveling and playing tennis. MEET THE INSTRUMENTS A string quartet consists of two violins, a viola and a cello. All of these instruments belong to the string family. -

Elias String Quartet BEETHOVEN the Complete String Quartets

b0073_WH booklet template.qxd 08/12/2014 22:57 Page 1 Elias String Quartet BEETHOVEN The Complete String Quartets Op. 18 No. 4 Op. 74 ‘Harp’ Opp. 130 & 133 1 b0073_WH booklet template.qxd 08/12/2014 22:57 Page 2 Elias string QuartEt plays BEEthovEn – 1 There is something particularly special about replace the fugue with a slighter final movement. Beethoven’s cycle of string quartets. At the heart This does so much to change the experience of the of Beethoven’s life’s statement as a composer, work as a whole that the Elias String Quartet they are pieces that one simply needs to know. played Op. 130 twice in their Wigmore Hall cycle, The cycle of piano sonatas may be more complete. once with each finale – an excellent idea. The five cello sonatas are perhaps the most Arguably, if I had to choose a single Beethoven perfectly concise and representative series. The work to sum him up as a composer, this would be symphonies of course are the mightiest of all, it. Written on a grand scale, it contains the whole each a masterpiece. Every one of these cycles world within it: earthiness, humour, monstrous inspired and also weighed heavily upon the intellect, heaven and hell, redemption. One may generations that followed but the cycle of choose one’s own words of course because this sixteen string quartets has retained a special music is at once objective and also wonderfully status and reverence that perhaps eclipses all of abstract. It defies words. them. Why? The opening movement of Op.