IV Resource Issues, Opportunities, Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Eel Distribution and Dam Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay

Seboomook Lake American Eel Distribution and Dam Ripogenus Lake Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay Pittston Farm North East Carry Lobster Lake Watershed (Androscoggin and Canada Falls Lake Rainbow Lake Kennebec River Watersheds) Ragged Lake a d a n Androscoggin River Watershed (3,526 sq. miles) a C Upper section (1,363 sq. miles) South Twin Lake Rockwood Lower section (2,162 sq. miles) Kokadjo Turkey Tail Lake Kennebec River Watershed (6,001 sq. miles) Moosehead Lake Wood Pond Long Pond Long Pond Dead River (879 sq. miles) Upper Jo-Mary Lake Upper Section (1,586 sq. miles) Attean Pond Lower Section (3,446 sq. miles) Number Five Bog Lowelltown Lake Parlin Estuary (90 sq. miles) Round Pond Hydrology; 1:100,000 National Upper Wilson Pond Hydrography Dataset Greenville ! American eel locations from MDIFW electrofishing surveys Spencer Lake " Dams (US Army Corps and ME DEP) Johnson Bog Shirley Mills Brownville Junction Brownville " Monson Sebec Lake Milo Caratunk Eustis Flagstaff Lake Dover-Foxcroft Guilford Stratton Kennebago Lake Wyman Lake Carrabassett Aziscohos Lake Bingham Wellington " Dexter Exeter Corners Oquossoc Rangeley Harmony Kingfield Wilsons Mills Rangeley Lake Solon Embden Pond Lower Richardson Lake Corinna Salem Hartland Sebasticook Lake Newport Phillips Etna " Errol New Vineyard " Madison Umbagog Lake Pittsfield Skowhegan Byron Carlton Bog Upton Norridgewock Webb Lake Burnham e Hinckley Mercer r Farmington Dixmont i h s " Andover e p Clinton Unity Pond n i m a a Unity M H East Pond Wilton Fairfield w e Fowler Bog Mexico N Rumford -

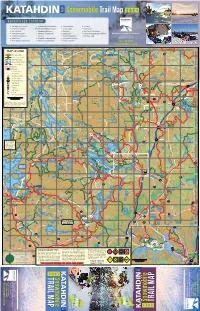

Snowmobile Trail Map 2021

KATAHDIN AREA Snowmobile Trail Map 2021 ADVERTISER LOCATOR 1 The Nature Conservancy 8 Katahdin Federal Credit Union 14 Shin Pond Village 21 Scootic In 2 Katahdin Inn & Suites Millinocket Memorial Hospital 15 5 Lakes Lodge 22 Libby Camps 3 Baxter Park Inn 9 Matagamon Wilderness 16 Flatlanders 23 River Driver’s Restaurant 4 Pamola Motor Lodge 10 Raymond’s Country Store 17 Bowlin Lodge 24 Friends of Katahdin Woods & Waters Katahdin Area Chamber of Commerce 1029 Central Street 5 Katahdin General Store 11 Chester’s 18 Katahdin Valley Motel 25 Mt. Chase Lodge Millinocket, ME 04462 6 Baxter Place 12 Brownville Snowmobile Club 19 Chesuncook Lake House 7 New England Outdoor Center 13 Wildwoods Trailside Cabins 20 Lennie’s Superette 207-723-4443 KatahdinMaine.com Advertiser List 1 New England Outdoor CenterO Eagle Advertiser List xbow Rd 470000 480000 490000 500000 2 Katahdin510000 Inn & Suites 520000 530000 540000 550000 ITS 560000 570000 Allagash Lake J o 1 New England Outdoor Center 5130000 h 3 Baxter Park Inn 86 Lake d 5130000 n m R s kha Advertiser 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola List Inn Lodge& Suites MAP LEGEND B Haymock Pin Millinocket r id Lake 1 New 3 BaxterEngland Park Outdoor Inn Center Li 71D g Lake 5 Kathdin General Store22 bb e y Pinnac Rd 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola Inn Lodge& Suites le Grand ITS 6 Katahdin Federal Credit Union Lo 11 TO THE o Lake Umcolcus 83 ITS Corridor Trails 3 Baxter 5 Kathdin 7Park Raymond’s Inn General Store TRAINS p Seboeis Lake 4 Pamola 6 Katahdin 8 Lodge Wildwoods Federal TrailsideCredit Union Millimagassett 3A Groomed Local Club Tr. -

Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 1-1-2008 Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation "Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules" (2008). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 479. http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/479 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR & COMMISSIONER With an impressive inventory of 6,000 lakes and ponds, 3,000 miles of coastline, and over 32,000 miles of rivers and streams, Maine is truly a remarkable place for you to launch your boat and enjoy the variety and beauty of our waters. Providing public access to these bodies of water is extremely impor- tant to us because we want both residents and visitors alike to enjoy them to the fullest. The Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife works diligently to provide access to Maine’s waters, whether it’s a remote mountain pond, or Maine’s Casco Bay. How you conduct yourself on Maine’s waters will go a long way in de- termining whether new access points can be obtained since only a fraction of our waters have dedicated public access. -

Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’S Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1-2018 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W. Geller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Geller, William W., "Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake" (2018). Maine History Documents. 135. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/135 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps Part 2 Sporting Camps Introduction The Beginning of the Sporting Camp Era Chapter 8 Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenus Lake Pre-1894: Camps and People Post-1894: Nicatou to North Twin Dam Post-1894: Norcross Community Post-1894: Camps on the Lower Chain Lakes On the River: Ambajejus Falls to Ripogenus Dam At Ambajejus Lake At Passamagamet Falls At Debsconeag Deadwater At First and Second Debsconeag Lakes At Hurd Pond At Daisey Pond At Debsconeag Falls At Pockwockamus Deadwater At Abol and Katahdin Streams At Foss and Knowlton Pond At Nesowadnehunk Stream At the Big Eddy At Ripogenus Lake Outlet January 2018 William (Bill) W. -

Visitor's Guide

MAINE KatahdinMaine.com VISITOR’S GUIDE Welcome Stop at the Chamber office at 1029 Central Street, Millinocket for trails, maps, guidance and more! Download the Discover Katahdin App so you can access information while on the move. Maine is home to many mountains and several state parks but there is only one mile-high Katahdin, the northern terminus INSIDE of the Appalachian Trail, located in the glorious Baxter State ATV Trails Park. Located right “next door” is the Katahdin Woods and & Rules ........... 63-65 Waters National Monument. These incredible places are right Multi-Use Trail here in the Katahdin Region. Make us your next destination— Map (K.R.M.U.T.) .... ......................66-67 for adventures in our beautiful outdoors, and experiences like none other. Let us help you Discover Your Maine Thing! Canoeing & Kayaking .........56-61 Located in the east central portion of the state, known as The Map ............... 50-51 Maine Highlands, the Katahdin region boasts scenic vistas Children’s Activities ...18 and abundant wildlife throughout northern Penobscot Coun- ty’s hilly lake country, the rolling farm country of western Pe- Cross-Country Skiing nobscot, and southern Aroostook’s vast softwood flats. The & Snowshoeing....68-71 area is home to incredible wildlife; including our local celeb- Maps ............. 72-79 rity the moose, as well as osprey, bald eagles, blue herons, Directory beaver, black bear, white-tailed deer, fox and more. of Services ...... 82-97 Festivals ...............98 Visit in spring, summer and fall to enjoy miles of hiking trails—from casual walks to challenging hikes, kayaking and Getting Here .......... 5 canoeing on pristine lakes, white water rafting with up to Katahdin Area Class V rapids, world class fishing for trout, landlocked salmon Hikes .............. -

Penobscot River Corridor & Seboomook Public Land

www.parksandlands.com Property History When to Visit Bureau of Parks and Lands and Parks of Bureau he rivers, streams, and lakes in the Seboomook/Pe- The best paddling is between May and September, with the fish- nobscot region were highways for native people, who ing usually best in either of those “shoulder season” months. Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry and Conservation Agriculture, Thave been present here for nearly 12,000 years. Canoe Recreational dam releases tend to occur on Saturdays during routes in the region date back at least 1,000 years, linking the July, August and September: call GLHA at 1- 888-323-4341 Maine Department of Department Maine Kennebec, Penobscot, and Allagash rivers, are still enjoyed for more on Canada Falls and Seboomook dam releases. For today by recreational paddlers traveling the historic 740-mile more on timing of McKay Station (Ripogenus Dam) releases, Northern Forest Canoe Trail. call Brookfield Power at 1-888-323-4341. Some of these paddling routes were taken by writer and naturalist Mosquitoes and black flies are thickest in late May through Overview Upper West Branch and Lobster Lake Henry David Thoreau on three extended trips between 1846 and July. Various types of hunting take place in fall, with bear bait 1857. Thoreau’s The Maine Woods describes his journey into a season generally during September, moose hunting from late he upper reaches of the Penobscot River run through a The wildest portion of the corridor, the Upper West Branch wild landscape that attracted both adventurers and lumbermen. September through mid-October, and firearms season for deer mountainous, forested landscape defined by the power- offers scenic canoeing, camping and fishing (with gentle waters in November. -

Mount Katahdin and Its Vast Vacation Country ; Mount Katahdin Canoeing Fishing & Camping Bangor & Aroostook Railroad

Maine State Library Digital Maine Bangor and Aroostook Railroad Collections 1917 Mount Katahdin and its Vast Vacation Country ; Mount Katahdin Canoeing Fishing & Camping Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/bangor_and_aroostook Recommended Citation Bangor & Aroostook Railroad, "Mount Katahdin and its Vast Vacation Country ; Mount Katahdin Canoeing Fishing & Camping" (1917). Bangor and Aroostook. 2. https://digitalmaine.com/bangor_and_aroostook/2 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Railroad Collections at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bangor and Aroostook by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BANGOR & A R O O S*T O O K RAILROAD Famous Mt. Katahdin as it Appears from a Point on the West Branch Canoe Trip Mt. Katahdin and Its Vast Vacation Country famous as “The Nation’s Playground,” and it is largely because of the popularity of the Maine woods that she has had bestowed . KATAHDIN, the highest peak in Maine and upon her this enviable title. Katahdin’s summit is visible from the second highest in New England, is the many points miles distant, and the great peak—maternal rather outstanding scenic feature of Maine. Its loca than menacing in its massiveness—seems to extend the welcom tion, as a glance at the map will show, makes it ing nod to the thousands who look to Maine for vacation out the dominating point from which radiates north, ings, canoe trips, fishing and hunting. Katahdin has been placed south, east and west, a vast expanse of country which is the most by good old Mother Nature right in the midst of a vast terri famous vacation section of the continent. -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) ) COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLAN For Areas Within the Jurisdiction of the Maine Land Use Regulation Commission Department of Conservation Maine Land Use Regulation Commission Approved March 27, 1997 Maine has always been proud of its wildlands -- the Big Woods, land ofIndian and trapper, of white pine tall enough for masts on His Majestys ships, of mountain lion, moose, and eagle. Much ofthe wildness was still there when Thoreau went in by birchbark canoe, a little over a century ago. And much ofit remains. There is spruce and fir, moose and beaver, lake and mountain whitewater enough to satisfy generations ofAmericans. More and more, as northeastern US. develops, the Maine woods are becoming an almost unparalleled resource, both for tree production and for recreational opportunity. But who is to come forward to say that this resource must not be squandered? Can we guarantee that the next generations will be able to set out in a canoe and know that adventure is just around the bend? "Report on the Wildlands" State of Maine Legislative Research Committee Publication 104-1 A, 1969 STATE OF MAINE OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR 1 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUST A, MAINE 04333-0001 ANGUS S. KING, JR. GOVERNOR March 27, 1997 Land Use Regulation Commission Members Department of Conservation 22 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0022 Dear Commission Members: I am pleased to approve the Land Use Regulation Commission's revised Comprehensive Land Use Plan. -

Baxter State Park Were in Effect in July, August and September

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) F 27 ,P5 B323 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. DIRECTOR'S 1995 SUMMARY B. OPERATIONAL IDGHLIGHTS AND OVERVIEW I OVERVIEW - 1995 II TRAINING III SEARCH AND RESCUE IV SAFETY V PUBLIC RELATIONS VI SPECIAL ACTIVITIES VII NEW CONSTRUCTION - REGIONS I AND II VIII LAW ENFORCEMENT IX MAINTENANCE X PROJECTION OF MAJOR PROJECTS FOR '96-'97 XII APPENDIX C. SCIENTIFIC FOREST MANAGEMENT AREA A. ISSUES AND ADMINISTRATION B. FOREST EDUCATION C. FOREST OPERATIONS D. OTHER ACTIVITIES D. INFORMATIONIEDUCATION I PUBLIC PROGRAMS II ENRICHMENTIEXCHANGES III COMMITTEES IV INFORMATIONIEDUCATION V VISITOR INFORMATION CENTER VII APPENDIX E. ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES I PERSONNEL CHANGES II TRAINING III CONTRACT SERVICES IV SUPPLY V DONATION ACCOUNT VI PERSONNEL LISTING a. ORGANIZATION CHART b. YEAR ROUND c. SEASONAL VII STATISTICAL REPORT F. FINANCIAL REPORT G. DIRECTOR'S CONCLUDING REMARKS H. APPENDIX I AUTHORITY/ADVISORY LISTING/SUB-COMMITTEES II DIRECTOR'S COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE III SCIENTIFIC FOREST MANAGEMENT AREA ADVISORY IV DIRECTOR'S RESEARCH COMMITTEE (Fonnerly Scientific Study Review Committee) V DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE OF CONTROVERSIAL ISSUES THAT AROSE IN 1995 VI 1995 ADMINISTRATIVE CAMP USE A. DIRECTOR'S 1995 SUMMARY DIRECTOR'S 1995 SUMMARY It is our pleasure to provide you a report on the accomplishments within our operation during calendar year 1995. We are finding that each year becomes more complex in a complex world filled with issues of modem technology, interest of controversy and a schedule that requires more hours than are available in a day. -

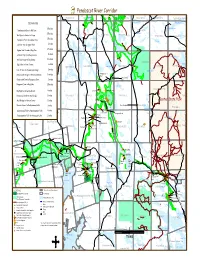

Penobscot River Corridor

Penobscot River Corridor rancis Lake Allagash Lake T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R10 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 J Haymock Lake Millinocket Lake DISTANCES U 0 2 5 miles Little Millinocket Lake Semboomook Dam to Roll Dam T7 R11 WELS Fourth Lake 5 5 miles T7 R15 WELS T7 R14 WELS T7 R13 WELS T7 R12 WELS Roll Dam to Penobscot Farm T7 R10 WELS T7 R9 WELS T7 R8 2 5 miles Little Sha low Lake Penobscot Farm to Lobster Trip Third Lake 3 miles Chamberlain Lobster Trip to Ogden Point Lake Shallow Lake Ogden Point to end of Big Claw 4 5 miles Caucomgomoc Lake Lobster Trip to Halfway House 8 miles Second Matagamon Lake Halfway House to Big Island 2 5 miles T6 R11 WELS 6 miles First Matagamon Big Island to Pine Stream - T6 R15 WELS T6 R14 WELS Umbazooksus Lake T6 R12 WELS T6 R10 WELS Trout Brook Twp Pine Stream to Chesuncook Village 3 miles Webster Lake Umbazooksus / 16 miles Loon Lake T6 R8 Chesuncook Village to Chesuncook Dam West 2 Umbazooksus Telos Lake Chesuncook Dam to Ripogenus Dam 3 miles 3 L East Ripogenus Dam to Big Eddy 2 5 miles Cuxabexis Lake 2 Nesourdnahunk Twp 2 Big Eddy to Horserace Brook 4 miles Canvas Dam Longley Stream Horserace Brook to Abol Bridge 5 miles T5 R15 WELS T5 R14 WELS Chesuncook Twp T5 R12 WELS T5 R8 W Gero 12 Abol Bridge to Nevers Corner 2 miles Boomhouse Gero 2 Baxter State Park 2 Gero 3 4 Gero 4 Nevers Corner to Desbsconeag Falls 3 miles Telos Checkpoint T5 R11 WELS Little Ragmuff T5 R9 WELS Nesowadnehunk Lake Debsconeag Falls to Passamagamet Falls 4 miles 2 Smart's Pine Stream -

An Annotated Catalogue of the Fishes of Maine

ITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHillMS S3iaVdan— LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN — I c/5 c/) ::; > (o dvaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiws CO ± CO ± (/) \ 5 ITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHimS SBIHVaan libraries SMITHSONIAN yvyan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi NiviNOSHims'^ CO UJ CO CO " "" Z _j 2 -J 2 'ITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHllWS S3ldVdan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN 2 r- , 2 r- 2 > XI . — M-: m ~ _ I/) — CO — CO avyan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiii/ms _ CO riTUTiON NOIinillSNI MVINOSHIINS SBIbV^an libraries SMITHSONIAN CO _ -:, 'X ^ ^ CO O Xi^osvi^ _ O _ 2 _| 2 avnan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiims CD > CO = CO ± O) TITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHIIIMS S3liiVyan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN w ..-. w ^ (/) 2 ^ ^ 2 2 ^<^° MuJi ^NOIinillSNI NVlN0SHillMs'^S3IHVHan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTI <^ ~ D z \ ^ /^—^ z C Z -J z 'libraries SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIlDillSNI NVlNOSHimS S3IMVy5 r- 03 ol > ;o y^ ± o) £ c/> NOIinillSNI NVINOSHlllMS S3 1 MV^ 8 11 LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN z INSTITUT fi z ^ ^ .cf- ^ 2 LIBRARIEs'^SMITHSONlAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVIN0SHlllMs'^S3 I d Vd 7 ^ ^ </) 2 ^ <^ ^ 9 ,.-.. </5 /--^^ ^ /^f^\ ~ /^- ' ^ /^^^ ~ /^it^^ ^ ^"^fe - /^^ NOIinillSNI~^NVINOSHllWS S3ldVHa!l LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUT E C/5 £ C/5 ± C/) LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHIIIMS S3IHVdl C/J C/) 2 > ^ -ZL •, <Si Z CO '•*" CO ' 2 CO Z C/3 -2 NOIinillSNI NVINOSHlll^S S3liJVdan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUT </5 — CO ^ \ ^, ^ ^ CO *^ Ife ^^ c W 31 < .^^ ^ CQ Z _J Z _j z LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHlltMS S3ldVd z f~ -z. x~ ^ CO _ CO £ C/) \ Z NOIinillSNI NviNosHiiws S3iavdan libraries Smithsonian institut .,. CO Z ^, ^ 2 W 2 Vol. Ill, i*"- Part 1. PROCEEDINGS PORTLAND SOCIETY NATURAL HISTORY. Organized 1843. CONTENTS. -

In the Maine Woods 7 Women in the Maine Woods 11 Mountain Climbing in Maine 15 Moosehead Lake and Its Resorts 23

THE uOMPLlMBNTS OF BANGOR & / 00 K iiiiit iiiiii railrOIO BANGOR, MAINE ^ibrarg ISORTHEASTERN UNIVERStTY UBRARY 7> FOREWORD O the Bangor S)C Aroostook Rail- road — in the interests of which this book \s published — belongs the credit of the development of that wonderful section of agricul- tural wealth, Northern Maine. To the Merrill Trust Company, more than any one banking institution in the state, the develop- ment of many of the larger Maine enterprises is due. Its assets, to the extent of 95 per cent, are invested here in Maine. It believes in Maine, in its people and its resources. Through its long-established Bond Department it offers investors everywhere the securities of Maine properties affording the two most important in- vestment elements — Safety and Yield. Its Banking Service is uns'irpassed. It is glad at any time to furnish detailed informa- tion of its investments or its banking facilities. ITS ADDRESS IS MERRILL TRUST COMPANY BANGOR, MAINE The BANGOR & AROOSTOOK RAILROAD COMPANY BANGOR MAINE George M.Houghton Pc3ssenyer 'Crai/Yic i 11 J. Bangor dC Aroostook Railroad Company WILFRID A. HENNESSY, Editor Published by the Passenger Traffic Department, to whom all communications should be addressed Extracts from this book are allowed provided full credit is given the Bangor 6C Aroostook R. R. A copy of this book will be sent to any address on receipt of ten cents in stamps by GEO. M. HOUGHTON, Passenger Traffic Manager, Bangor 6C Aroostook Railroad Company, Bangor, Maine. TABLE OF CONTENTS In the Maine Woods 7 Women in the Maine Woods 11 Mountain Climbing in Maine 15 MoosEHEAD Lake and its Resorts 23 The Bangor & Aroostook Service to the Restigouche .