Structural Tension in Jonathan Harvey's String Trio and Slate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludwig Van Beethoven: the String Trios

Ludwig van Beethoven: The String Trios Sinae Baek, violin Cesia Corrales, viola Paul Christopher, cello Program Notes by Jackson Harmeyer Tonight’s program centers on the trios of Beethoven, and we hear two of these—numerically the first and the last in The genre of string trio was one which occupied Ludwig his catalogue. The String Trio in E-flat major, Opus 3, is van Beethoven for only a few years. All five of his trios for Beethoven’s earliest, published in 1796. Much like the trio violin, viola, and cello were written in the 1790s and by Mozart, which he had titled “Divertimento,” published in Vienna. Beethoven would write no further Beethoven’s Opus 3 is in six movements and follow his string trios after starting his impressive cycle of sixteen same pattern. Both trios begin with a fast first movement string quartets in 1798. Yet, alongside the one string trio which applies sonata principle; they continue with a slow produced by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the five created second movement, a minuet, another slow movement, and by Beethoven are regarded as the greatest works of their another minuet; and finally conclude with a fast sixth genre produced in the eighteenth century. Together they movement in rondo form. Beethoven even snatches mark the first pinnacle in this genre’s history, as Mozart’s conspicuous key signature of E-flat major, one Beethoven’s turn away from the string trio would prove which would have posed difficulties for string players of symptomatic of a larger trend: though the eighteenth that era. -

Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz

Classics & Jazz PAID Permit # 79 PRSRT STD PRSRT Late Fall 2020 U.S. Postage Aberdeen, SD Jazz New Naxos Bundle Deal Releases 3 for $30 see page 54 beginning on page 10 more @ more @ HBDirect.com HBDirect.com see page 22 OJC Bundle Deal P.O. Box 309 P.O. 05677 VT Center, Waterbury Address Service Requested 3 for $30 see page 48 Classical 50% Off beginning on page 24 more @ HBDirect.com 1/800/222-6872 www.hbdirect.com Classical New Releases beginning on page 28 more @ HBDirect.com Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz We are pleased to present the HBDirect Late Fall 2020 Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz Catalog, with a broad range of offers we’re sure will be of great interest to our customers. Catalog Index Villa-Lobos: The Symphonies / Karabtchevsky; São Paulo SO [6 CDs] In jazz, we’re excited to present another major label as a Heitor Villa-Lobos has been described as ‘the single most significant 4 Classical - Boxed Sets 3 for $30 bundle deal – Original Jazz Classics – as well as a creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music.’ The eleven sale on Double Moon, recent Enlightenment boxed sets and 10 Classical - Naxos 3 for $30 Deal! symphonies - the enigmatic Symphony No. 5 has never been found new jazz releases. On the classical side, HBDirect is proud to 18 Classical - DVD & Blu-ray and may not ever have been written - range from the two earliest, be the industry leader when it comes to the comprehensive conceived in a broadly Central European tradition, to the final symphony 20 Classical - Recommendations presentation of new classical releases. -

The Trio Sonata in 17Th-Century Italy LONDON BAROQUE

The Trio Sonata in 17th-Century Italy LONDON BAROQUE Pietro Novelli (1603 – 47): ‘Musical Duel between Apollo and Marsyas’ (ca. 1631/32). Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen, France. BIS-1795 BIS-1795_f-b.indd 1 2012-08-20 16.40 London Baroque Ingrid Seifert · Charles Medlam · Steven Devine · Richard Gwilt Photo: © Sioban Coppinger CIMA, Giovanni Paolo (c. 1570–1622) 1 Sonata a Tre 2'56 from Concerti ecclesiastici… e sei sonate per Instrumenti a due, tre, e quatro (Milan, 1610) TURINI, Francesco (c. 1589–1656) 2 Sonata a Tre Secondo Tuono 5'57 from Madrigali a una, due… con alcune sonate a due e tre, libro primo (Venice, 1621/24) BUONAMENTE, Giovanni Battista (c. 1595–1642) 3 Sonata 8 sopra La Romanesca 3'25 from Il quarto libro de varie Sonate… con Due Violini & un Basso di Viola (Venice 1626) CASTELLO, Dario (fl. 1st half 17th C) 4 Sonata Decima a 3, Due Soprani è Fagotto overo Viola 4'35 from Sonate concertate in stil moderno, libro secondo (Venice 1629) MERULA, Tarquinio (c. 1594–1665) 5 Chiaconna 2'32 from Canzoni overo sonate concertate… a tre… libro terza, Opus 12 (Venice 1637) UCCELLINI, Marco (c. 1603–80) 6 Sonata 26 sopra La Prosperina 3'16 from Sonate, correnti… con diversi stromenti… opera quarta (Venice 1645) FALCONIERO, Andrea (c. 1585–1656) 7 Folias echa para mi Señora Doña Tarolilla de Carallenos 3'17 from Il primo Libro di canzone, sinfonie… (Naples, 1650) 3 CAZZATI, Maurizio (1616–78) 8 Ciaconna 2'32 from Correnti e balletti… a 3. e 4., Opus 4 (Antwerp, 1651) MARINI, Biagio (1594–1663) 9 Sonata sopra fuggi dolente core 2'26 from Per ogni sorte d’stromento musicale… Libro Terzo. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

String Trio String Quartet String Quartet +

String Trio Magma – sparks of sound for violin, viola and cello (13’) www.hefti.net/en/work/54/ String Quartet Ph(r)asen – string quartet no. 1 (18’) www.hefti.net/en/work/14/ Guggisberg-Variationen – string quartet no. 1 (18’) www.hefti.net/en/work/11/ Mobile – string quartet no. 3 (26’) www.hefti.net/en/work/38/ con fuoco – string quartet no. 4 (12’) www.hefti.net/en/work/41/ Concubia nocte – string quartet no. 5 (9’) music for the second nocturnal vigil www.hefti.net/en/work/72/ Fünf Szenen für Gustav – string quartet no. 6 (16’) www.hefti.net/en/work/81/ String Quartet + An durchsichtigen Fäden – for mezzo soprano and string quartet (30’) to a poem by Kurt Aebli www.hefti.net/en/work/70/ Danse interstellaire – mourning music for basset clarinet and string quartet (23’) www.hefti.net/en/work/57/ Up-to-date as of September 2020 Rückert-Lieder (G. Mahler / arr. D. P. Hefti) – for high voice and string quartet (23’) to poems by Friedrich Rückert www.hefti.net/en/work/75/ String Sextet Monumentum – music for string sextet (19’) 2 Vl, 2 Vla, 2 Vcl www.hefti.net/en/work/55/ Piano Pieces Schattenklang – adagio for piano (12’) www.hefti.net/en/work/19/ Beethoven-Resonanzen – piano piece no. 2 (11’) www.hefti.net/de/werk/42/ Resonanzen II – piano piece no. 3 (5’) www.hefti.net/en/work/63/ Ritmico – piano piece no. 4 (3’) www.hefti.net/en/work/68/ Duo with Piano Poème lunaire – for viola and piano (9’) www.hefti.net/en/work/10/ Poème noctambule – for violin and piano (14’) www.hefti.net/en/work/25/ Up-to-date as of September 2020 Trio with Piano à la recherche.. -

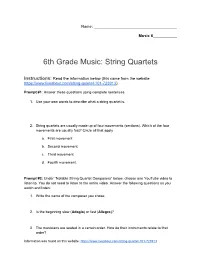

6Th Grade Music: String Quartets

Name: ______________________________________ Music 6___________ 6th Grade Music: String Quartets Instructions: Read the information below (this came from the website https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913). Prompt #1: Answer these questions using complete sentences. 1. Use your own words to describe what a string quartet is. 2. String quartets are usually made up of four movements (sections). Which of the four movements are usually fast? Circle all that apply a. First movement b. Second movement c. Third movement d. Fourth movement. Prompt #2: Under “Notable String Quartet Composers” below, choose one YouTube video to listen to. You do not need to listen to the entire video. Answer the following questions as you watch and listen: 1. Write the name of the composer you chose. 2. Is the beginning slow (Adagio) or fast (Allegro)? 3. The musicians are seated in a certain order. How do their instruments relate to that order? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 4. How do the musicians respond to each other while playing? Prompt #3: Under Modern String Quartet Music, find the Love Story quartet by Taylor Swift. Listen to it as you answer using complete sentences. 1. Which instrument is plucking at the beginning of the piece? (If you forgot, violins are the smallest instrument, violas are a little bigger, cellos are bigger and lean on the floor). 2. Reflect on how this version of Love Story is different from Taylor Swift’s original song. How would you describe the differences? What does this version communicate? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 String Quartet 101 All You Need to Know About the String Quartet The Jerusalem Quartet, a string quartet made of members (from left) Alexander Pavlovsky, Sergei Bresler, Kyril Zlontnikov and Ori Kam, perform Brahms’s String Quartet in A minor at the 92nd Street Y on Saturday night, October 25, 2014. -

2021-2022 Concert Season CHAMBER MUSIC CHARLESTON

2021-2022 Concert Season CHAMBER MUSIC CHARLESTON CHAMBER MUSIC CHARLESTON Dear friends, February 1, 2021 Sandra Nikolajevs, President & Artistic Director [email protected] Post Office Box 80072, Charleston, SC 29416 Music has the unique ability to help us through difficult times, providing 843.763.4941 glimpses of beauty, moments of reflection, and time for escape and healing. The current 2020-2021 concert season is unlike any other we have Board of Directors experienced, and I am continually in awe of the outpouring of support that has Griff Hogan, Chair been shown to CMC. Thanks to you, we are in a strong position to create a Rosa Fullerton Nelson Hicks season of celebration for 2021-2022: a celebration of the return of live music Joe Lambright paired with a celebration of CMC’s 15th anniversary. Susan Lobell There is so much to highlight from the upcoming season: the acclaimed Sally Gray Lovejoy violinist Rachel Barton Pine and harpsichordist Jory Vinikour will join us for a Susan Parsons spectacular season opening event in September; virtuoso bassist Xavier Foley Katie Roberts and violinist Francisco Fullana will perform Vaughan William’s luxurious Piano Charles Tremann Quintet with our musicians in the spring of 2022; favorite returning artists Performing Musicians for the 2021-2022 Season* including Anthea Kreston, Amy Schwartz Moretti, Andrew Armstrong and Jason Andrew Armstrong, piano Duckles will bring their exuberant musicianship to the Dock Street Theatre, Phillip Bush, piano Daniel Ching, violin playing alongside the CMC strings for music of Brahms, Mahler and Dohnányi. Jason Duckles, cello Music of Brahms, Schumann, Mozart, Borodin and Haydn will fill South Carolina Xavier Foley, double bass Society Hall and a potpourri of instrumental combinations will return to the living Francisco Fullana, violin rooms of private residences on Kiawah Island, Bishop Gadsden and Downtown Zac Hammond, oboe Charleston. -

Contemporary Music Score Collection

UCLA Contemporary Music Score Collection Title La Fleur Du Ciel Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3s31v9qb Author Dietz, Christopher Publication Date 2020 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CHRISTOPHER DIETZ LA FLEUR DU CIEL for string trio LA FLEUR DU CIEL for string trio: violin, viola, cello Approximate duration: 8 minutes Performance notes Scordatura tunings: Violin Viola Cello G-D-G#-E C-F#-D-A C-G-C#-A • Pitches played on the scordatura strings of each instrument are indicated with the following symbol: + • These scordatura pitches are notated as if the string on which it is being played is still in standard tuning. • To clarify any misunderstanding in relation to scordatura or harmonic notation, a score containing sounding pitches is supplied above the instructional notation. Notation: • Accidentals carry throughout the measure in the register in which they appear. • The notation utilized instructs the player as to both which open string to use as well as where to finger on that string: La fleur du ciel was composed for the East Coast Contemporary Ensemble and premiered at Le Moulin à Nef in Auvillar, France in July 2010. CHRISTOPHER DIETZ LA FLEUR DU CIEL for string trio (2010) The trio is a reflection on the passage from Camus posted below. “At the time, I often thought that if I had to live in the trunk of a dead tree, with nothing to do but look up at the sky flowering overhead, little by little I would have got used to it. I would have waited for birds to fly by or clouds to mingle, just as here I waited to see my lawyer’s ties and just as, in another world, I used to wait patiently until Saturday to hold Marie’s body in my arms.” Camus, Albert. -

Chamber Music Repertoire Trios

Rubén Rengel January 2020 Chamber Music Repertoire Trios Beethoven , Piano Trio No. 7 in B-lat Major “Archduke”, Op. 97 Beethoven , String Trio in G Major, Op. 9 No. 1 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 2 in C Major, Op. 87 Brahms , Horn Trio E-lat Major, Op. 40 U. Choe, Piano Trio ‘Looper’ Haydn, P iano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 Haydn, Piano Trio in C Major, Hob. XV: 27 Mendelssohn , Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 Mendelssohn, Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Op. 66 Mozart , Divertimento in E-lat Major, K. 563 Rachmaninoff, Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor Ravel, Piano Trio in A minor Saint-Saëns , Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 18 Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 Stravinsky , L’Histoire du Soldat Tchaikovsky, Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 Quartets Arensky , Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Cellos in A minor, Op. 35 No. 2 (Viola) Bartok, String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Sz. 40 Bartok , String Quartet No. 5, Sz. 102, BB 110 Beethoven , Piano Quartet in E-lat Major, Op. 16 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, Op. 18 No. 4 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 5 in A Major, Op. 18 No. 5 Beethoven, String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2 Borodin , String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Debussy , String Quartet in G Major, Op. 10 (Viola) Dvorak, Piano Quartet No. 2 in E-lat Major, Op. -

Free Direct Shuttles Lisbon-Marvão

UNDER THE HIGH PATRONAGE PRINCIPAL PATRONS EN PATRONS PROMOTERS David James & Friends (former Hilliard Ensemble) Officium Ensemble Joseph Moog Fabrice Millischer Manuel Fischer-Dieskau Juliane Banse SUPPORT MEDIA PARTNERS Martin Mitterrutzner Erika Pluhar / António Victorino d’Ameida Christoph Poppen Horácio Ferreira Novus String Quartet Raphaela Gromes DESIGN ORGANISATION DESIGN + COMUNICAÇÃO FREE DIRECT SHUTTLES LISBON-MARVÃO +info: marvaomusic.com Cologne Chamber Orchestra Anna-Doris Capitelli Athens State Orchestra Coro Gulbenkian Veronika Eberle Edicson Ruiz marvaomusic.com /th /st /th July July July 28Saturday /th Tuesday, 26th June 21 July Thursday /th Saturday 26 ESCUSA, São João Church PRELUDE CONCERT & DINNER July Marvão, Casa da Cultura 25Wednesday Marvão, Igreja do Espírito Santo 11.00 CHAMBER MUSIC RECITAL /th MONFORTE, Torre de Palma Wine Hotel MURIEL CANTOREGGI, VIOLIN 10.00 LECTURE: THE HISTORY OF MARVÃO /nd 11.00 STUDENT CONCERT 27Friday July HARIOLF SCHLICHTIG, VIOLA 18.00 WELCOME DRINKS Marvão, São Tiago Church (IN ENGLISH) BY JOAQUIM CARVALHO July ESART - Escola Superior de Artes Aplicadas RAPHAELA GROMES, VIOLONCELLO FREE ADMISSION 16.00 DUO RECITAL de Castelo Branco Marvão, Casa da Cultura 29Sunday 19.00 CONCERT Bach Sonata for solo violin, in A minor, BWV1003 XENON SAXOPHONE QUARTET FREE ADMISSION 10.00 LECTURE: THE HISTORY OF AMMAIA Lachenmann Toccatina for solo violin 22Sunday MANUEL FISCHER-DIESKAU, VIOLONCELLO Marvão, N. Sra. da Estrela Church works by GRIEG, ALVARADO, BOZZA, BACH, São Tiago Church CONNIE SHIH, PIANO (IN PORTUGUESE) BY JOAQUIM CARVALHO Schubert String Trio in B flat major, D. 581 SCHMITT AND PIAZZOLLA 11.00 HOLY MASS & HAYDN MASS 11.00 PIANO RECITAL GALEGOS, São Sebastião Church BEETHOVEN The complete cello sonatas - PART 1 Marvão, Casa da Cultura FREE ADMISSION 21.00 DINNER BY CHEF FILIPE RAMALHO JOSEPH MOOG /th Sonata No. -

Seattle Chamber Music Festival Repertoire, 1982

SEATTLE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY REPERTOIRE LIST, 1982–2020 “THIRTY-NINE YEARS OF BEAUTIFUL MUSIC” James Ehnes, Artistic Director Toby Saks (1942-2013), Founder Adams, John Anonymous (arr. Delaware Staigers) China Gates for Piano (2013) Carnival of Venice for Trumpet and Piano (2003W) Hallelujah Junction for Two Pianos (2012, 2017W) Road Movies for Violin and Piano (2013) Arensky, Anton Piano Quintet in D major, Op. 51 (1997, 2003, 2011W) Aho, Kalevi Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 32 (1984, 1990, 1992, 1994, 2001, 2007, 2010O, ER-OS (2018) 2016W) Piano Trio in F minor, Op. 73 (2001W, 2009) Albéniz, Isaac Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Celli in A minor, Op. 35 (1989, 1995, 2008, Iberia (3 selections from) (2003) 2011) Iberia “Evocation” (2015) Six Piéces for Piano, Op. 53 (2013) Alexandrov, Kristian Arlen, Harold Prayer for Trumpet and Piano (2013) Wizard of Oz Fantasy (arr. William Hirtz) (2002) Applebaum Arnold, Malcolm "Landscape of Dreams" (1990) Sonatina for Oboe and Piano, Op. 28 (2004) Andres, Bernard Babajanian, Arno Narthex for Flute and Harp (2000W) Piano Trio in F sharp minor (2015) Anderson, David Bach, Johann Sebastian Capriccio No. 2 for Solo Double Bass (2006) “Aus liebe will mein Heiland sterben” from St. Matthew Passion BWV 244 Four Short Pieces for Double Bass (2006) (for flute, arr. Bennett) (2019) Brandenburg Concerto No 3 in G major, BWV 1048 (2011) Anderson, Jordan Brandenburg Concertos (Complete) BWV 1046-1051 (2013W) Drafts for Double Bass and Piano (2006) Capriccio “On the Departure of a Beloved Brother” in B flat -

New Perspectives on Classical Music Through the Work of Mark Oâ

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2005 Crossing Over in the 21st Century: New Perspectives on Classical Music Through the Work of Mark O’Connor, Edgar Meyer, and Béla Fleck Louanne Marie Iannaccone University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Iannaccone, Louanne Marie, "Crossing Over in the 21st Century: New Perspectives on Classical Music Through the Work of Mark O’Connor, Edgar Meyer, and Béla Fleck. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2014 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Louanne Marie Iannaccone entitled "Crossing Over in the 21st Century: New Perspectives on Classical Music Through the Work of Mark O’Connor, Edgar Meyer, and Béla Fleck." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Dr. Leslie C. Gay, Jr., Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Dr. Wesley Baldwin, Dr. Rachel Golden Carlson Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R.