Commonwealth of Massachusetts Appeals Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fuel Forecourt Retail Market

Fuel Forecourt Retail Market Grow non-fuel Are you set to be the mobility offerings — both products and Capitalise on the value-added mobility mega services trends (EVs, AVs and MaaS)1 retailer of tomorrow? Continue to focus on fossil Innovative Our report on Fuel Forecourt Retail Market focusses In light of this, w e have imagined how forecourts w ill fuel in short run, concepts and on the future of forecourt retailing. In the follow ing look like in the future. We believe that the in-city but start to pivot strategic Continuously pages w e delve into how the trends today are petrol stations w hich have a location advantage, w ill tow ards partnerships contemporary evolve shaping forecourt retailing now and tomorrow . We become suited for convenience retailing; urban fuel business start by looking at the current state of the Global forecourts w ould become prominent transport Relentless focus on models Forecourt Retail Market, both in terms of geographic exchanges; and highw ay sites w ill cater to long customer size and the top players dominating this space. distance travellers. How ever the level and speed of Explore Enhance experience Innovation new such transformation w ill vary by economy, as operational Next, w e explore the trends that are re-shaping the for income evolutionary trends in fuel retailing observed in industry; these are centred around the increase in efficiency tomorrow streams developed markets are yet to fully shape-up in importance of the Retail proposition, Adjacent developing ones. Services and Mobility. As you go along, you w ill find examples of how leading organisations are investing Further, as the pace of disruption accelerates, fuel their time and resources, in technology and and forecourt retailers need to reimagine innovative concepts to become more future-ready. -

For the Fuel & Convenience Store Industry

FOOT TRAFFIC REPORT FOR THE FUEL & CONVENIENCE STORE INDUSTRY Q1 2017 A NEW ERA FOR THE CONVENIENCE STORE As the convenience store industry adapts to meet customer needs and grow market share, location intelligence is becoming increasingly critical to understanding consumer habits and behaviors. GasBuddy and Cuebiq teamed up in the first quarter of 2017 to issue the first foot traffic report for the fuel and convenience store industry. Highlights: GasBuddy and Cuebiq examined 23.5 million consumer trips to the pumps and convenience stores between January 1 and March 31. In Q1, more than half of GasBuddies visited locations within six miles of their homes or places of employment, giving retailers the opportunity to leverage their greatest resource—knowing their customer base—to localize and personalize their product selection. Weekdays between 11:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m. were highly-trafficked hours in Q1. Convenience stores are poised to lure business away from QSRs and grocery stores now that customers can eat quality meals at the same place and time they choose to fill up their tanks. With filling a gas tank clocking in at an efficient 2-3 minutes, the 73% of GasBuddies who spent more than five minutes at locations in Q1 demonstrated that consumers are likely willing to spend some time in store before or after visiting the pumps. QUARTERLY FOOT TRAFFIC REPORT 1 GasBuddy examined nearly 23.5 million consumer trips to gas Indiana-based gas station and stations and c-stores in Q1 2017 convenience store chain Ricker’s enjoys a loyal GasBuddy customer Which fuel brands captured the base—the nearly 50-station brand highest ratio of footfall per station? captured more than 4x the industry average footfall per location in Q1. -

Newsletterwinter2014

NEWSLETTERWINTER2014 WELCOME NRC Realty & Capital Advisors, LLC is pleased to provide you with its first quarterly newsletter dealing with topics of interest to owners and operators in the convenience store and gasoline station industry. Given our industry experience and expertise, particularly as it relates to real estate and financial services, we believe that we are able to provide a wide array of information that should be of benefit to you and your business. In this inaugural issue, we begin a four-part series on Finally, we have enclosed an article entitled “NRC Achieves “Understanding the Value of Your Business.” The first article Banner Year in 2013” which highlights the notable in the series is “Why Should I Have My Company Valued?” transactions that NRC was involved in last year. Again, and is written by Evan Gladstone, Executive Managing looking at recent transactions and trends will provide a good Director and Ian Walker, Senior Vice President. “barometer” of things to look for in the future. This issue also contains a reprint of the “2013 C-Store We at NRC are excited about our quarterly newsletter and Industry Year in Review: An M&A and Capital Markets hope that you will find it of value. Should you have any Perspective” written by Dennis Ruben, Executive Managing questions about anything contained in this newsletter or any Director, which first appeared online on CSP Daily News other matter, please feel free to contact Evan Gladstone on January 8th through 10th as a three-part series. A at (312) 278-6801 or [email protected], Dennis review of that article should prove to be particularly useful Ruben at (480) 374-1421 or [email protected], or in understanding where the industry has been recently and Ian Walker at (312) 278-6830 or [email protected]. -

2020-0040-Se

BOARD OF ZONING APPEALS CASE SUMMARY FOR SPECIAL EXCEPTION 2022, 2034, 2040 Marion Street & 1408, 1414, 1420 Elmwood Avenue & 2019 Bull Street September 3, 2020 at 4:00 P.M. Case Number: 2020-0040-SE Subject Property: 2022, 2034, 2040 Marion Street & 1408, 1414, 1420 Elmwood Avenue & 2019 Bull Street (TMS#s 09016-07-01, -02, -03, -04, -06, -17 & -18) Zoning District: C-3 (General Commercial District), -DD (City Center Design/Development District) Applicant: Florence Abrenica, GeenbergFarrow Property Owner: Brownstein Associates, LLC Summary Prepared: July 13, 2020 Requested Action: Special exception to permit a gasoline service station and convenience store Applicable Sections of Zoning Ordinance: §17-258 Gasoline Service Stations (SIC 554) permitted in C-3 districts by special exception §17-258 Convenience Stores (SIC 541.1) permitted in the C-3 districts by special exception §17-297 Additional criteria and standards for special exception approval of convenience stores §17-112 Standard criteria for special exceptions Case History: N/A Staff Comments: The applicant is requesting a special exception to permit a gasoline service station and a special exception to permit convenience store on the parcel. The special exceptions will be reviewed together but voted on individually. Part I: The applicant is requesting a special exception to permit a gasoline service station. The subject property consists of seven commercially developed lots. Once the lots are combined, the proposed property will be +/- 1.7-acres. Applicant intends to construct a ten (10) pump fuel dispenser with canopy. Part II: The applicant is also requesting a special exception to permit a convenience store. -

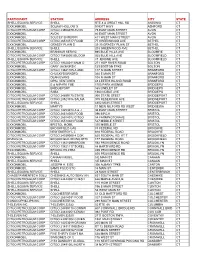

Fuel Street City State Postal Code County ABG002 United Supermarkets LLC

GTVID Retailer Brand - Fuel Street City State Postal Code County ABG002 United Supermarkets LLC. 2160 Pine Street Abilene TX 79601 Taylor County ABW002 South West Convenience Stores Alon 1050 South Treadaway Boulevard Abilene TX 79602 Taylor County ABW003 South West Convenience Stores Alon 2718 North 1st Street Abilene TX 79603 Taylor County ABW011 South West Convenience Stores Alon 1374 S Clack St Abilene TX 79605 Taylor County ABW020 South West Convenience Stores Alon 3151 Oldham Ln Abilene TX 79602 Taylor County ABW021 South West Convenience Stores Alon 4142 Clack Street Abilene TX 79601 Taylor County ABW022 South West Convenience Stores Alon 3749 West Lake Road Abilene TX 79601 Taylor County ABW036 South West Convenience Stores Alon 965 East South 11th Street Abilene TX 79602 Taylor County ABW037 South West Convenience Stores Alon 5150 US-277 Abilene TX 79605 Taylor County ABW039 South West Convenience Stores Alon 2150 North Treadaway Boulevard Abilene TX 79601 Taylor County ABW040 South West Convenience Stores Alon 3350 Catclaw Drive Abilene TX 79606 Taylor County ABW041 South West Convenience Stores Alon 1302 South 14th Street Abilene TX 79602 Taylor County ABW042 South West Convenience Stores Alon 241 E Stamford St Abilene TX 79601 Taylor County ABW049 South West Convenience Stores Alon 641 Butternut Street Abilene TX 79602 Taylor County ABW052 South West Convenience Stores Alon 4102 Loop 322 Abilene TX 79602 Taylor County ABW053 South West Convenience Stores Alon 4809 South 14th Street Abilene TX 79605 Taylor County ABW054 South West Convenience Stores Alon 8101 US-83 Abilene TX 79602 Taylor County SAG005 Landmark Industries Shell 12220 US Highway 87 East Adkins TX 78101 Bexar County SAG027 Pruski's Market, Inc. -

FOOT TRAFFIC REPORT for the Fuel & Convenience Retailing Industry

FOOT TRAFFIC REPORT for the fuel & convenience retailing industry Q1 2018 FOOT TRAFFIC REPORT Q1 2018 GasBuddy and Cuebiq examined more than 32.6 million consumer visits to fuel and convenience retailers between January 1 and March 31, 2018. This data provides actionable insights into consumer behavior and the factors that influence foot traffic. HIGHLIGHTS: New Rankings System This report now separates fuel and convenience brands into four categories based on the number of locations. Brands who received the most foot traffic per station in their respective categories include Ohio-based Speedway (1000+ locations), Washington-based Costco (250 – 999 locations), Kentucky-based Thorntons (50 – 249 locations) and Indiana-based Ricker’s (30 – 49 locations). Better Offerings, Better for Business In the 1000+ location category, four of the top five are convenience brands that emphasize in-store offerings. Speedway captured the top spot in this category following improvements in their fresh food service and putting a bigger emphasis on their loyalty program. Cumberland Farms #1 in Most States Cumberland Farms captures the highest average footfall traffic in six states, all of New England, despite falling short of the Top 10 overall within its category of 250 to 999 locations. Wawa comes in second with five states, including hotly-contested Pennsylvania. Costco and Kroger tie for third place with four states, and Speedway and Pilot tie for fifth place with three each. Hump Day is the Busiest Pump Day Wednesday at 5 p.m. was the busiest time time for fuel and convenience brands, followed by Friday from 4-6 p.m. -

Circle K W/Exxon 109 Sequoyah Access Rd | Soddy-Daisy, Tn

109 Sequoyah Access Rd | Soddy-Daisy, TN Offering memorandum 1 CIRCLE K W/EXXON 109 SEQUOYAH ACCESS RD | SODDY-DAISY, TN LISTED BY: CHRIS SANDS ASSOCIATE DIR (925) 718-7524 MOB (781) 724-7846 [email protected] LIC # 02103311 (CA) CHUCK EVANS SENIOR ASSOCIATE DIR (925) 319-4035 MOB (925) 323-2263 [email protected] LIC # 01987860 (CA) BROKER OF RECORD KYLE MATTHEWS table of contents LIC # 263667 (TN) EXECUTIVE financial tenant AREA SUMMARY SUMMARY SUMMARY OVERVIEW 3 4 6 11 2 REPRESENTATIVE PHOTO section 1 executive SUMMARY INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS • Absolute NNN ownership ideal for hands-off landlords with the ability to capitalize on accelerated depreciation • Strong hedge against inflation with 6.50% increases every 5 years • Location benefits from a total of 12 pumps allowing for constant business • Property is sitting outparcelled to a Food City-anchored shopping center on the main drive from Highway 27 • Over the past 10 years, Soddy-Daisy has seen an almost 13% growth in population within a 1-mile radius • Extremely stable corporate guarantee backing the lease with a market cap of nearly $40 billion 3 section 2 FINANCIAL overview 4 Investment Summary TENANT Summary » OFFERING PRICE $2,295,000 Lease Type Absolute NNN Tenant Circle K Stores Inc » CAP RATE 7.88% Lease Guarantor Circle K Stores Inc » TOTAL BUILDING AREA ±9,396 SF Roof & Structure Tenant Responsible » TOTAL LAND AREA ±1.32 AC (±57,325 SF) Rent Commencement Date Thursday, October 16, 2003 Lease Commencement Date Thursday, October 16, 2003 » NOI $180,915 Lease -

Open PDF File, 1.94 MB, for August 3, 2018 Brief of Exxon Mobil Corporation

Case 18-1170, Document 69, 08/03/2018, 2359373, Page1 of 125 18-1170 IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT EdXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, Plaintiff-Appellant, —against— MAURA TRACY HEALEY, In her official capacity as ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF MASSACHUSETTS, BARBARA D. UNDERWOOD, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW YORK, in her official capacity, Defendants-Appellees. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK BRIEF AND SPECIAL APPENDIX FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT THEODORE V. WELLS, JR. PATRICK J. CONLON DANIEL J. TOAL DANIEL E. BOLIA PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, WHARTON EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION & GARRISON LLP 22777 Springwoods Village Parkway 1285 Avenue of the Americas Spring, Texas 77389 New York, New York 10019 (832) 648-5500 (212) 373-3000 JUSTIN ANDERSON PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, WHARTON & GARRISON LLP 2001 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 (202) 223-7300 Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant Exxon Mobil Corporation Case 18-1170, Document 69, 08/03/2018, 2359373, Page2 of 125 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1, Plaintiff-Appellant Exxon Mobil Corporation states that it has no parent corporation and no publicly held company owns 10% or more of its stock. Case 18-1170, Document 69, 08/03/2018, 2359373, Page3 of 125 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities ................................................................................................. iii I. Preliminary Statement .................................................................................... -

Stripes Convenience Store & Gas Station

STRIPES CONVENIENCE STORE & GAS STATION 925 Fredericksburg Road, San Antonio, Texas 78201 *Representative Photo *Property Currently Under Contruction Exclusively Offered By: Michael Campbell Ed Colson, Jr. CCIM 619.546.0122 619.546.0121 [email protected] [email protected] CA Lic #01843521 CA Lic #01382996 | TX Lic #635820 OFFERING STATEMENT / DISCLAIMER InvestCore Commercial presents this Offering which business or affairs of the Property or the Owner since contents to any other entity (except to outside advisors has been prepared by InvestCore Commercial for use the date of preparation of the package. Analysis and retained by you, if necessary, for your determination of by a limited number of parties and does not purport verification of the information contained in this package whether or not to make a proposal and from whom you to provide a necessarily complete summary of the is solely the responsibility of the prospective purchaser. have obtained an agreement of confidentiality) without Property or any of the documents related thereto, nor Additional information and an opportunity to inspect the the prior written authorization of Owner or InvestCore does it purport to be all-inclusive or to contain all of Property will be made available upon written request to Commercial, (iv) not use the package or any of the the information which prospective investors may need interested and qualified prospective investors. contents in any fashion or manner detrimental to the or desire. All projections have been developed by interest of Owner or InvestCore Commercial, and (v) to InvestCore Commercial, the Owner, and designated Owner and InvestCore Commercial each expressly return it to InvestCore Commercial immediately upon sources and are based upon assumptions relating to reserve the right, at their sole discretion, to reject any request of InvestCore Commercial or Owner. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 Annual Report CONTENTS II To our shareholders IV Positioning for a lower-carbon energy future VI Energy for a growing population Scalable technology solutions VIII Providing energy and products for modern life IX Progressing advantaged investments X Creating value through our integrated businesses XII Upstream XIV Downstream XV Chemical XVI Board of Directors 1 Form 10-K 124 Stock performance graphs 125 Frequently used terms 126 Footnotes 127 Investor information ABOUT THE COVER Delivery of two modules to the Corpus Christi Chemical Project site in 2020. Each module weighed more than 17 million pounds, reached the height of a 17-story building, and was transported more than 5 miles over land. Cautionary Statement • Statements of future events or conditions in this report are forward-looking statements. Actual future results, including financial and operating performance; demand growth and mix; planned capital and cash operating expense reductions and efficiency improvements, and ability to meet or exceed announced reduction objectives; future reductions in emissions intensity and resulting reductions in absolute emissions; carbon capture results; resource recoveries; production rates; project plans, timing, costs, and capacities; drilling programs and improvements; and product sales and mix differ materially due to a number of factors including global or regional changes in oil, gas, or petrochemicals prices or other market or economic conditions affecting the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries; the severity, length and ultimate -

Susser Completes Acquisition of Sac-N-Pac Convenience Stores

Susser Completes Acquisition of Sac-N-Pac Convenience Stores 1/30/2014 HOUSTON and CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas, Jan. 30, 2014 /PRNewswire/ -- Susser Holdings Corporation (NYSE: SUSS) and Susser Petroleum Partners LP (NYSE: SUSP) today announced the closing of their previously announced acquisition of the convenience store assets and fuel distribution contracts of Sac-N-Pac Stores, Inc. and 3W Warren Fuels, Ltd. The Sac-N-Pac chain includes 47 convenience stores in the rapidly growing South Central Texas corridor between San Antonio and Austin. Sac-N-Pac operates its proprietary food service concept in 23 stores, six of which also include a branded food service concept. 3W Warren Fuels supplied approximately 65 million gallons of motor fuel annually to the 47 Sac-N-Pac locations and to approximately 20 independent dealer locations. SUSP has taken over the wholesale fuel supply for all of these locations, which are currently branded under Exxon, Shell and Valero flags. The acquisition is expected to be accretive to both SUSS and SUSP. The total purchase price was approximately $88 million plus inventories. All 47 of the Sac-N-Pac stores are fee properties. The acquisition also includes one stand-alone branded quick-serve restaurant, five raw tracts of land for future store development and the right to acquire two additional tracts. SUSS plans to initially operate all of the 47 stores under the Sac-N-Pac brand. Over time, the Company may elect to convert some of the sites to the Stripes brand, may add the Laredo Taco Co. brand to certain locations or may elect to convert some sites to the Company's wholesale dealer network. -

Participant Station Address City State Shell/Equiva Service Shell Rte 8 & Great Hill Rd Ansonia Ct Exxonmobil Squaw Hollow X

PARTICIPANT STATION ADDRESS CITY STATE SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL RTE 8 & GREAT HILL RD ANSONIA CT EXXONMOBIL SQUAW HOLLOW X 9 NOTT HWY ASHFORD CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 23908079 AVON 75 EAST MAIN STREET AVON CT EXXONMOBIL AVON 80 EAST MAIN STREET AVON CT EXXONMOBIL SOUCEY ENTERPR 411 WEST MAIN STREET AVON CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 26514517 FOOD 77 GREENWOOD AVE BETHEL CT EXXONMOBIL GRASSY PLAIN S 33-35 GRASSY PLAIN ST BETHEL CT SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL 203 GREENWOOD AVE BETHEL CT EXXONMOBIL BRANMAR SERVIC 985 BLUE HILLS AVE BLOOMFIE CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 15458003 BLOOM 925 BLUE HILL AVE BLOOMFIELD CT SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL 47 JEROME AVE BLOOMFIELD CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 19328011 M&M O 271 HOP RIVER ROAD BOLTON CT EXXONMOBIL GARY JACKOPSIC 129 BOSTON TPKE BOLTON CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 13821105 A AND 117 N MAIN STREET BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL CHUCKYS BRNDFD 364 E MAIN ST BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL DEAN EVANS 108 N MAIN ST BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL OPAL VENTURES 48 LEETES ISLAND ROAD BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL E & M PARK FUE 1705 PARK AVENUE BRIDGEPO CT EXXONMOBIL BRIDGEPORT 565 LINDLEY ST BRIDGEPO CT EXXONMOBIL SABA 1360 NOBLE AVE BRIDGEPO CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 24899175 STATE 900 STATE STEET BRIDGEPORT CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 20524016 SALMA 915 RESERVOIR AVE BRIDGEPORT CT SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL 4402 MAIN STREET BRIDGEPORT CT EXXONMOBIL MARTYS 11 NEW MILFORD RD WEST BRIDGEWA CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 14253014 A & J 36 EAST MAIN STREET BRISTOL CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 26514005 FOOD 396 BIRCH