Policing During India's Covid-19 Lockdown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Om Prakash Singh, DGP, Uttar Pradesh Police, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

To Om Prakash Singh, DGP, Uttar Pradesh Police, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Dear Sir, Even as people across the nation mourned Mahatma Gandhi on Wednesday, January 30, 2018, CJP is appalled to note that one group disrespected both Gandhi and his legacy in a callous and violent fashion. Through our newly launched Hate Hatao app, we were alerted to a viral video that shows Hindu Mahasabha national secretary Pooja Shakun Pandey chanting "Mahatma Nathuram Godse amar rahe" (Long live Mahatma Nathuram Godse) before shooting at an effigy of Gandhi, after which fake blood can be seen pooling at the bottom of the effigy. The effigy is then set on fire. The incident took place in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh. Godse, who assassinated Gandhi on January 30, 1948, was a member of the Hindu Mahasabha. Pandey "later told reporters that her organisation has started a new tradition by recreating the assassination, and it will now be practised in a manner similar to the immolation of demon king Ravana on Dussehra," NDTV reported, adding that the Hindu Mahasabha "regards the day of Mahatma Gandhi's death as Shaurya Divas (Bravery Day), in honour of Nathuram Godse". The Times of India reported that Pandey told the media that Gandhi was responsible for India’s Partition that led to the birth of Pakistan, and that Godse’s act of killing him was admirable. NDTV noted that in 2015, Hindu Mahasabha leader Swami Pranavananda "had announced plans to install statues of Nathuram Godse across six districts of Karnataka," and had called him " a 'patriot' who had worked with the blessings of Hindu nationalist Vinayak Damodar Savarkar." CJP appreciates the Aligarh Police’s prompt move to register charges against 13 people, including Pandey herself. -

Impact Assessment of Modernization of Police Forces (MPF)

Impact Assessment of Modernization of Police Forces (MPF) Impact Assessment of Modernization of Police Forces (MPF) (From 2000 to 2010) Bureau of Police Research and Development Ministry of Home Affairs 2010 Impact Assessment of MPF Scheme Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................................. 4 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 11 Terms of reference .................................................................................................................. 12 Scope of Work ......................................................................................................................... 13 Expectations from Consultant .............................................................................................. 13 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY ADOPTED ..................................................... 15 Methodology Adopted by M/S Ernest and Young........................................................... 15 STATES/UTS COVERED UNDER THIS IMPACT ASSESSMENT .................................................. 16 METHODOLOGY ADOPTED BY THE BPR&D................................................................ 28 CHAPTER 3: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS - E&Y ......... 32 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ........................................................................................... 32 Overview of Funds Utilized................................................................................................. -

“Everyone Has Been Silenced”; Police

EVERYONE HAS BEEN SILENCED Police Excesses Against Anti-CAA Protesters In Uttar Pradesh, And The Post-violence Reprisal Citizens Against Hate Citizens against Hate (CAH) is a Delhi-based collective of individuals and groups committed to a democratic, secular and caring India. It is an open collective, with members drawn from a wide range of backgrounds who are concerned about the growing hold of exclusionary tendencies in society, and the weakening of rule of law and justice institutions. CAH was formed in 2017, in response to the rising trend of hate mobilisation and crimes, specifically the surge in cases of lynching and vigilante violence, to document violations, provide victim support and engage with institutions for improved justice and policy reforms. From 2018, CAH has also been working with those affected by NRC process in Assam, documenting exclusions, building local networks, and providing practical help to victims in making claims to rights. Throughout, we have also worked on other forms of violations – hate speech, sexual violence and state violence, among others in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Bihar and beyond. Our approach to addressing the justice challenge facing particularly vulnerable communities is through research, outreach and advocacy; and to provide practical help to survivors in their struggles, also nurturing them to become agents of change. This citizens’ report on police excesses against anti-CAA protesters in Uttar Pradesh is the joint effort of a team of CAH made up of human rights experts, defenders and lawyers. Members of the research, writing and advocacy team included (in alphabetical order) Abhimanyu Suresh, Adeela Firdous, Aiman Khan, Anshu Kapoor, Devika Prasad, Fawaz Shaheen, Ghazala Jamil, Mohammad Ghufran, Guneet Ahuja, Mangla Verma, Misbah Reshi, Nidhi Suresh, Parijata Banerjee, Rehan Khan, Sajjad Hassan, Salim Ansari, Sharib Ali, Sneha Chandna, Talha Rahman and Vipul Kumar. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1808 , 31/07/2017 Class 43

Trade Marks Journal No: 1808 , 31/07/2017 Class 43 Priority claimed from 29/01/2010; Application No. : 757385 ;Thailand 1981226 17/06/2010 AMARI CO.LTD. 2013 , NEW PETCHABURI RD , BANGKRAPI , HUAYKWANG , BANGKOK , THAILAND 10320 SERVICE PROVIDERS. A CORPORATION ORGANIZED AND EXISTING UNDER THE LAWS OF THAILAND Address for service in India/Agents address: CHADHA & CHADHA. F-46, HIMALYA HOUSE, 23 KASTURBA GANDHI MARG, NEW DELHI -110001. Proposed to be Used DELHI RENTAL OF TEMPORARY ACCOMMODATION; HOTELS; HOTEL RESERVATIONS; RESTAURANTS; BAR SERVICES; CAFES. 6980 Trade Marks Journal No: 1808 , 31/07/2017 Class 43 1992412 13/07/2010 MOHIT MADAN trading as ;GOOD TIMES RESTAURANTS PVT. LTD. 29, SHIVAJI MARG, SECOND FLOOR, NEW DELHI - 15 SERVICE PROVIDER A COMPANY DULY INCORPORATED UNDER COMPANIES ACT 1956. Address for service in India/Attorney address: S. SINGH & ASSOCIATES 213, 3RD FLOOR PARMANAND COLONY, DR. MUKHERJEE NAGAR DELHI-9 Proposed to be Used DELHI RESTAURANTS , CATERING SERVICES FOR THE PROVISION OF FOOD AND DRINK, CAFES, CAFETERIAS, SNACK BARS, RESTAURANTS, SELF SERVICE RESTAURANTS, FAST FOOD RESTAURANTS, CANTEENS, COFFEE SHOPS AND ICE CREAM PARLOURS INCLUDED IN CLASS 42. THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER.. 6981 Trade Marks Journal No: 1808 , 31/07/2017 Class 43 Vista Grand 1994275 16/07/2010 SHEEL FOODS LTD. trading as ;SHEEL FOODS LTD. PLOT NO-6 7 7 SECTOR-29 GURGAON HARYANA SERVICE & PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: LAKSHYA LAW GROUP B-28, SECTOR-53, NOIDA, U.P-201304 Proposed to be Used To be associated with: 1949015, 1949016 DELHI HOTELS, MOTELS, RESTAURANT CAFETERIA LOUNGE BAR RESORT LODGING PROVISION OF FACILITIES FOR MEETINGS, CONFERENCES AND EXHIBITIONS. -

9 1 2019 10 20 40 Tender2

From Downloaded www.upsrtc.com From Downloaded www.upsrtc.com From Downloaded www.upsrtc.com SAHARANPUR REGION GENERAL CANDIDATES NO. S.NO NAME FATHER TOTAL OBT %DOB CASTE REGI. AMO ADDRESS Adh INETE NCC ITI A Ex Ard MAR RETIR O . MARKS AINE NO. UNT ar R & LEVE Arm h ATK E LEV D 10TH L y Sani ASH EMPL EL Man k RIT OYEE Bal 1 584 SACHIN NATH HANSRAJ 1000 707 70.7 02-Jul-94 General SRE- 200 VILL AND POST- AZAMPUR, DISTT- YES YES YES GOND GOND 26548 AZAMGARH, PIN- 276125 2 585 AMARNATH RAJENDRA 2240 158370.67 09-Dec-89 General SRE- 200 OLD HAAT ROAD NEAR NAHAR TCP YES YES YES PRASAD 30268 TEKANPUR GWALIOR MP , PINCODE -475005 3 586 SACHIN RAMVEER 1100 777 70.64 10-Jul-98 General SRE- 200 Village asdharmai post marauri distt budaun YES YES YES KUMAR SINGH 12356 243631 4 587 MUKESH RAM PAL 1000 706 70.6 14-Sep-94 General SRE- 200 VILL DANIYARPUR POST KOTWA THANA YES YES YES SINGH SINGH 13566 PHARDHAN DISTT LAKHIMPUR KHERI PIFromN 262805 5 588 Ankit Kumar Rakesh Kumar500 353 70.6 14-Jan-95 General SRE- 200 h-63 Amarpur Ghari Basoud Baghpat Pin YES YES YES 11104 Code- 20601 6 589 AMAN PRATEEK 1000 706 70.6 02-Jul-95 General SRE- 200 VILLAGE ADHYANA POST NAKUR DISTT YES YES YES KUMAR KUMAR 9176 SAHARANPUR UP 247342 7 590 KUMAR SHYAM 500 353 70.6 25-Jan-96 General SRE- 200 37/31/28 mahaviran lane mutthiganj YES YES YES PRATEEK KUMAR 9821 allahabad SRIVASTAVA 8 591 NIRMAL JAY CHAND 500 353 70.6 08-Apr-97 General SRE- 200 VILL GHAGHPUR POST DADEVRA DIST YES YES YES KUMAR 27302 SITAPUR PIN 261404 YADAV 9 592 SATYAM RAJENDRA 500 353 70.6 17-Jul-97 -

India 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

INDIA 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for freedom of conscience and the right of all individuals to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion; mandates a secular state; requires the state to treat all religions impartially; and prohibits discrimination based on religion. It also states that citizens must practice their faith in a way that does not adversely affect public order, morality, or health. Ten of the 28 states have laws restricting religious conversions. In February, continued protests related to the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which excludes Muslims from expedited naturalization provisions granted to migrants of other faiths, became violent in New Delhi after counterprotestors attacked demonstrators. According to reports, religiously motivated attacks resulted in the deaths of 53 persons, most of whom were Muslim, and two security officials. According to international nongovernmental organization (NGO) Human Rights Watch, “Witnesses accounts and video evidence showed police complicity in the violence.” Muslim academics, human rights activists, former police officers, and journalists alleged anti-Muslim bias in the investigation of the riots by New Delhi police. The investigations were still ongoing at year’s end, with the New Delhi police stating it arrested almost equal numbers of Hindus and Muslims. The government and media initially attributed some of the spread of COVID-19 in the country to a conference held in New Delhi in March by the Islamic Tablighi Jamaat organization after media reported that six of the conference’s attendees tested positive for the virus. The Ministry of Home Affairs initially claimed a majority of the country’s early COVID-19 cases were linked to that event. -

C 201610281311477337.Pdf

No. of pages........... Sl. No. UTTAR PRADESH POLICE RADIO HEADQUARTERS, MAHANAGAR LUCKNOW -226006 Price : Rs.25000/- TENDER FORM CONTENTS:- 1. TENDER NOTICE 2. GUIDELINES/INSTRUCTIONS FOR PREPARATION & SUBMISSION OF TENDER 3. CONDITIONS OF AGREEMENT 4. TECHNICAL OFFER 5. FINANCIAL OFFER 6. CHECK LIST FOR SUBMITTING OFFER 7. TENTATIVE BOQ 8. TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS 9. PROFORMA FOR AUTHORITY LETTER OF OEM 10. PROFORMA FOR DECLARATION OF BIDDER 11. PROFORMA FOR AUTHORITY FOR SIGNING TENDER DOCUMENT 12. PROFORMA FOR BANK GUARANTEE FOR EMD 13. PROFORMA FOR BANK GUARANTEE FOR PERFORMANCE SECURITY 14. PROFORMA FOR INTEGRITY PACT (IP) 1 1.TENDER NOTICE 2 3 2. GUIDELINES/INSTRUCTIONS FOR PREPARATION & SUBMISSION OF TENDER (A) DOCUMENTS REQUIRED TO FILL TENDER FORM 1. All the certificates/documents mentioned in the tender notice/tender form or details of which are attached with the tender form must be submitted by the tenderers and should be valid and up-to- date. 2. If the tenderer is an Agent/Dealer/Supplier, they should submit the authority letter (in original) of their principal fulfilling under mentioned conditions. Proforma enclosed as Annexure-A. (Photocopy will not be accepted):- (a) The Tendering firms (if not manufacturer of the item) should submit along with their offer, an authority letter from their principals (who should be manufacturer) that they are their authorized agents / dealers. (b) It should clearly bring out the relation of principal and agent/dealer as the case may be. It should speak of territory and acts assigned to the agent/dealer. (c) The principal should commit themselves through this authority letter for short comings / defects / substandard supplies / supplies not according to norms or law of land etc. -

UTTAR PRADESH SHASAN GRIH (POLICE) ANUBHAG-10 NOTIFICATION Miscellaneous No 2548/6-Pu-10-2008-27(60)/2001 Lucknow Dated: Dece

UTTAR PRADESH SHASAN GRIH (POLICE) ANUBHAG-10 NOTIFICATION Miscellaneous No 2548/6-pu-10-2008-27(60)/2001 Lucknow Dated: December 2 , 2008 (FIRST AMENDMENT) No 201/VI-pu-10-09-27(60)/2009 Lucknow: Dated: April 02, 2009 (SECOMD AMENDMENT) No 203/6-iq-10/2010-27(7)/2008 TC Lucknow: Dated: January 19, 2010 (THIRD AMENDMENT) No: 203(1)6/pu-10/27(7)/2008TC Dated: Lucknow: 5-4-2010 (FOURTH AMENDMENT) No 102/VI-pu-10-11-27(7)/2008 T.C Dated: Lucknow: January 14, 2011 (FIFTH AMENDMENT) No 494/Chh-pu-10-2013-27(65)/2012 Dated: Lucknow: 01 March, 2013 (SIXTH AMENDMENT) No 1544/Chh-pu-10-2013-27(65)/2012 Dated: Lucknow: 06 June, 2013 (SEVENTH AMENDMENT) No 3038/Chh-pu-10-2013-27(65)/2012 Dated: Lucknow: December 11, 2013 In exercise of the powers under sub-sections (2) of section 46 read with sub-sections (3) of the Said section, section-2 of the Police Act, 1861 (Act no. 5 of 1861) and all other powers enabling 2 him in this behalf, the Governor pleased to make the following rules with a view to amending the Uttar Pradesh Sub-Inspector and Inspector (Civil Police) Service Rules, 2008: THE UTTAR PRADESH SUB-INSPECTOR AND INSPECTOR (CIVIL POLICE) SERVICE RULES, 2008. PART-I-GENERAL Short titles and 1.(1) These rules may be called the Uttar Pradesh Sub-Inspector commencement and Inspector (Civil Police) Service (Seventh Amendment) Rules, 2013. (2) They shall come into force with effect from the date of their publication in the gazette. -

Telephone Directory

HARYANA AT A GLANCE GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE OF Divisions 6 Sub-tehsils 49 HARYANA Districts 22 Blocks 140 Sub-divisions 71 Towns 154 Tehsils 93 Inhabited villages 6,841 AREA AND POPULATION 2011 TELEPHONE Geographical area (sq.kms.) 44,212 Population (lakh) 253.51 DIRECTORY Males (lakh) 134.95 Females (lakh) 118.56 Density (per sq.km.) 573 Decennial growth-rate 19.90 (percentage) Sex Ratio (females per 1000 males) 879 LITERACY (PERCENTAGE) With compliments from : Males 84.06 Females 65.94 DIRECTOR , INFORMATION, PUBLIC RELATIONS Total 75.55 & PER CAPITA INCOME LANGUAGES, HARYANA 2015-16 At constant prices (Rs.) 1,43,211 (at 2011-12 base year) At current prices (Rs.) 1,80,174 (OCTOBER 2017) PERSONAL MEMORANDA Name............................................................................................................................. Designation..................................................................................................... Tel. Off. ...............................................Res. ..................................................... Mobile ................................................ Fax .................................................... Any change as and when occurs e-mail ................................................................................................................ may be intimated to Add. Off. ....................................................................................................... The Deputy Director (Production) Information, Public Relations & Resi. .............................................................................................................. -

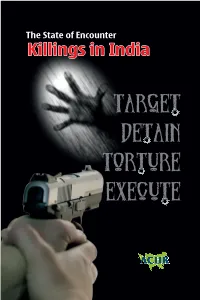

The State of Encounter Killings in India First Published November 2018

The State of Encounter Killings in India First published November 2018 © Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2018. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-88987-85-6 Suggested contribution Rs. 995/- Published by : ASIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS [ACHR has Special Consultative Status with the United Nations ECOSOC] C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi-110058, India Phone/Fax: +91-11-25620583 Email: [email protected] Website: www.achrweb.org Table of Contents 1. Executive summary ........................................................................................................... 7 2. The history and scale of encounter deaths in India ............................................................ 19 2.1 History of encounter killings in India ...................................................................... 20 2.2 Encounter killings in insurgency affected areas ..................................................... 20 2.3 Encounter killings by the police during 1998 to 2018 ............................................ 24 3. Modus operandi : Target, detain, torture and execute without any witness ....................... 27 3.1 Target and detain.................................................................................................. 27 3.2 Rare eye-witnesses .............................................................................................. 32 3.3 Torture of suspects before encounter killing ........................................................ -

Download (5.51

Annual Report 2013-14 CONTENTS CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER-2 HIGHLIGHTS 3 CHAPTER-3 NHRC : ORGANIZATION AND FUCNTIONS 21 CHAPTER-4 CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS 27 A. Terrorism and Militancy 27 B. Custodial Violence and Torture 28 C. Illustrative Cases 28 (a) Custodial Deaths 28 Judicial Custody 28 1. Death of Undertrial Prisoner Radhey Shyam at Sawai Man 28 Singh Hospital in Jaipur, Rajasthan (Case No. 168/20/14/09-10-JCD) 2. Suicide Committed by Prisoner in Tihar Jail, Delhi 30 (Case No. 378/30/9/2011-JCD) 3. Death of Undertrial Prisoner K. Yadagiri Goud in Sub-jail, 31 Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh (Case No. 269/1/3/2011-JCD) Police Custody 33 4. Death of Rama Shankar due to Police Torture in Chandauli 33 District, Uttar Pradesh (Case No. 30182/24/19/2010-AD, Linked Files 30528/ 24/19/2010-AD,32002/24/19/2010-AD,33025/24/19/ 2010-AD,Death of Ganesh31563/24/19/2010-AD) A. Bhosle due to Torture in Police Custody in Beed, Maharashtra 5. (Case No. 334/13/2006-2007-PCD) 35 NHRC | i Annual Report 2013-14 6. Suicide by S. Barla due to Torture in P.S. Kadamtala, 37 Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Case No. 3/26/0/07-08-PCD) 7. Death of Ajay Mishra in Davoh Police Station, Bhind, 38 Madhya Pradesh Para-Military/Defence Forces Custody 40 (CaseNo.675/12/7/2012-PCD) 8. 40 Border AtrocitiesonaYoungManByBSFJawansNearBangladesh 9. (CaseDeath No.of a134/25/13/2012-PF) Youth due to Torture by Sashastra Seema Bal 41 Personnel at Village Valmikinagar in West Champaran District, Bihar 10. -

JUA India 8/2015

HAUT-COMMISSARIAT AUX DROITS DE L’HOMME • OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; and the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders REFERENCE: UA IND 8/2015: 12 August 2015 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacities as Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment; Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; and Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 24/7, 19/10, 25/2, 24/5, and 25/18. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning the alleged arrest and detention of women human rights defenders Ms. Roma Mallik and Ms. Sukalo Gond. Ms. Roma Mallik is General Secretary of the All India Union of Forest Working People (AIUFWP). The AIUFWP works for the promotion and protection of the rights of the tribal and indigenous forest working community, on issues concerning land and environmental rights, forced evictions and access to natural resources.