Effect of Individual Incubation Effort on Home Range Size in Two Rallid Species (Aves: Rallidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: the role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity edited by A. J. Hails Ramsar Convention Bureau Ministry of Environment and Forest, India 1996 [1997] Published by the Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland, with the support of: • the General Directorate of Natural Resources and Environment, Ministry of the Walloon Region, Belgium • the Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark • the National Forest and Nature Agency, Ministry of the Environment and Energy, Denmark • the Ministry of Environment and Forests, India • the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Sweden Copyright © Ramsar Convention Bureau, 1997. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior perinission from the copyright holder, providing that full acknowledgement is given. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The views of the authors expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of the Ramsar Convention Bureau or of the Ministry of the Environment of India. Note: the designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Ranasar Convention Bureau concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: Halls, A.J. (ed.), 1997. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: The Role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity. -

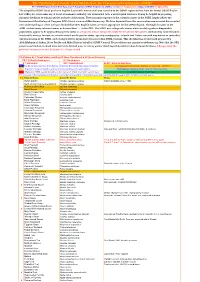

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 11 Chapter 11 Wetland Conservation Plan

CHAPTER 11 CHAPTER 11 WETLAND CONSERVATION PLAN 11.1 Wetland Management Conditions 11.1.1 Natural Parks and Reserves (1) Legal conditions for natural parks and reserves 1) National environmental policy The National Environmental Policy Plan (NEPP) for Latvia was accepted by the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia in 1995. NEPP reflects long-term strategy (25~30 years), and has two long-term goals, i) maintenance and protection of existing biodiversity and landscape characteristics of Latvia, and ii) sustainable use of natural resources. 2) National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) Since Latvia is a country with limited institutional, human, and financial resources, NEAP is incorporated with the National Biodiversity Strategy and the Action Plan, and it will also incorporate implementation of the Ramsar Strategic Plan. NEAP was adopted in 1997, and it emphasizes an establishment of administrative bodies for the Kemeri national park and Lake Engure which include several internationally important wetlands. An elaboration of the Integrated Management Plan for the Lubana Wetland Complex (LWC) is also placed high priority of nature conservation action. 3) Environmental laws and regulations Latvian environmental legal system has been prepared rapidly, and the following laws are relevant to protected areas, especially wetlands. a. The Environmental Protection Law (1991, 1997) determines the general environmental protection objectives, i.e. to ensure preservation of the genetic basis of nature, diversity of biotopes and landscape. It is an umbrella law on nature protection including land use and protection area planning. b. The Law on Specially Protected Nature Areas (1993, 1997) regulates the categories of protected natural areas, the procedure of their establishment and protection. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Birds and Biodiversity in Germany – 2010 Target

Birds and Biodiversity i n G e r m a n y Editors The Dachverband Deutscher Avifaunisten (DDA, Federation of German Avifaunists) co-ordinates national-wide bird survey programmes, such as monitoring of breeding and resting birds. As well get as supporting reseach on applied bird conservation, the DDA represents German nature conser- vation organisations on Wetlands International and the European Bird Census Council. 2010 Tar Since more than 100 years the Naturschutzbund Deutschland (NABU, Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union) is involved in practical and political bird and nature conservation. The NABU is the German partner of BirdLife International, it is member of the DNR (German League for Nature and Environment), and since 1971 the NABU chooses the Bird of the Year in Germany (2008: common cuckoo). The Deutsche Rat für Vogelschutz (DRV, German Council for Bird Protection) is a forum, which enables the co-operation and an intensive exchange of experiences between representatives of governmental bird conservation agencies, scientific institutions and NGOs. The aim is to give scientifically well-founded advice to decision takers and to promote scientific knowledge and conservation strategies. The Deutsche Ornithologen-Gesellschaft (DO-G, German Ornithologists’ Society) is one of the oldest scientific associations in the world. Since its formation in 1850, it has promoted ornithology as a pure science as well as in applied research. The Bundesamt für Naturschutz [Federal Nature Conservation Agency] has funded the printing of this -

Downloaded from the Data Zone at on 15/12/2009 8

RIS for Site no. 2435, Madatapa Lake, Georgia Ramsar Information Sheet Published on 5 October 2020 Georgia Madatapa Lake Designation date 8 July 2020 Site number 2435 Coordinates 41°10'57"N 43°46'53"E Area 1 398,00 ha https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/2435 Created by RSIS V.1.6 on - 5 October 2020 RIS for Site no. 2435, Madatapa Lake, Georgia Color codes Fields back-shaded in light blue relate to data and information required only for RIS updates. Note that some fields concerning aspects of Part 3, the Ecological Character Description of the RIS (tinted in purple), are not expected to be completed as part of a standard RIS, but are included for completeness so as to provide the requested consistency between the RIS and the format of a ‘full’ Ecological Character Description, as adopted in Resolution X.15 (2008). If a Contracting Party does have information available that is relevant to these fields (for example from a national format Ecological Character Description) it may, if it wishes to, include information in these additional fields. 1 - Summary Summary The site contains high mountain shallow freshwater lake, marshes, boggy meadows, rivers and streams. It is located in sub-alpine zone and is a part of by treeless mountain steppe landscape. The site represents one of the most important water bird habitats in the country. The wetland is typical for the biogeographical region. Madatapa lake is the part of Javakheti wetland system, located along the African-Eurasian migration flyways. the lake is a crucial stop-over and breeding site for many bird species, including globally threatened species and species included in National Red list of endangered species. -

Systematic List of the Romanian Vertebrate Fauna

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © Décembre Vol. LIII pp. 377–411 «Grigore Antipa» 2010 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-010-0028-1 SYSTEMATIC LIST OF THE ROMANIAN VERTEBRATE FAUNA DUMITRU MURARIU Abstract. Compiling different bibliographical sources, a total of 732 taxa of specific and subspecific order remained. It is about the six large vertebrate classes of Romanian fauna. The first class (Cyclostomata) is represented by only four species, and Pisces (here considered super-class) – by 184 taxa. The rest of 544 taxa belong to Tetrapoda super-class which includes the other four vertebrate classes: Amphibia (20 taxa); Reptilia (31); Aves (382) and Mammalia (110 taxa). Résumé. Cette contribution à la systématique des vertébrés de Roumanie s’adresse à tous ceux qui sont intéressés par la zoologie en général et par la classification de ce groupe en spécial. Elle représente le début d’une thème de confrontation des opinions des spécialistes du domaine, ayant pour but final d’offrir aux élèves, aux étudiants, aux professeurs de biologie ainsi qu’à tous ceux intéressés, une synthèse actualisée de la classification des vertébrés de Roumanie. En compilant différentes sources bibliographiques, on a retenu un total de plus de 732 taxons d’ordre spécifique et sous-spécifique. Il s’agît des six grandes classes de vertébrés. La première classe (Cyclostomata) est représentée dans la faune de Roumanie par quatre espèces, tandis que Pisces (considérée ici au niveau de surclasse) l’est par 184 taxons. Le reste de 544 taxons font partie d’une autre surclasse (Tetrapoda) qui réunit les autres quatre classes de vertébrés: Amphibia (20 taxons); Reptilia (31); Aves (382) et Mammalia (110 taxons). -

Wetlands Management for Little Crake (Porzana Parva) Conservation in a “Natura 2000” Site

2011 2nd International Conference on Environmental Science and Development IPCBEE vol.4 (2011) © (2011) IACSIT Press, Singapore Wetlands management for Little Crake (Porzana parva) conservation in a “Natura 2000” site A.N. Stermin, L.R. Pripon, A. David and I. Coroiu Babeş Bolyai University, Faculty of Biology and Geology, Dept. of Ecology and Taxonomy Cluj-Napoca, Romania [email protected] Abstract— Currently, around a quarter of all rail species are This species inhabits emergent vegetation in wetlands, globally threatened. Among these, the little crake (Porzana flooded valleys and water bodies like ponds and ditches [6, parva) is considered a conservation priority in Europe, and is 11]. In Europe, little crake populations are in decline [3]. The listed in Appendix I of the EU Wild Birds Directive, Appendix main threats to little crake populations come from habitat II of the Bern Convention, and Appendix II of the Bonn loss [10] and defective management of areas in which it lives Convention. In Europe, the main threat to little crake [9]. The little crake is poorly studied, because it is a secretive populations is represented by habitat loss. Our study species and its habitat is difficult to penetrate [11]. demonstrates how habitat loss, defective management of The main goals of our study is to show how habitat loss, habitats, and interspecific interactions with water rail (Rallus defective management of habitat, and interspecific aquaticus) are collectively contributing to the decline of little competition with water rail (Rallus aquaticus) contribute to crake effectives. We surveyed five wetlands from the Fizeş Basin, a “Natura 2000” site, located in the central part of the the decline of little crake effectives, in a context where the Transylvanian Plane of Romania (24°10’ E; 46°50’ N). -

Ramsar Information Sheet Published on 31 January 2017

RIS for Site no. 2284, Trappola Marshland - Ombrone River Mouth, Italy Ramsar Information Sheet Published on 31 January 2017 Italy Trappola Marshland - Ombrone River Mouth Designation date 13 October 2016 Site number 2284 Coordinates 42°40'14"N 11°01'03"E Area 536,00 ha https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/2284 Created by RSIS V.1.6 on - 24 March 2017 RIS for Site no. 2284, Trappola Marshland - Ombrone River Mouth, Italy Color codes Fields back-shaded in light blue relate to data and information required only for RIS updates. Note that some fields concerning aspects of Part 3, the Ecological Character Description of the RIS (tinted in purple), are not expected to be completed as part of a standard RIS, but are included for completeness so as to provide the requested consistency between the RIS and the format of a ‘full’ Ecological Character Description, as adopted in Resolution X.15 (2008). If a Contracting Party does have information available that is relevant to these fields (for example from a national format Ecological Character Description) it may, if it wishes to, include information in these additional fields. 1 - Summary 1.1 - Summary description Please provide a short descriptive text summarising the key characteristics and internationally important aspects of the site. You may prefer to complete the four following sections before returning to draft this summary. Summary (This field is limited to 2500 characters) The site Trappola marshland - Ombrone River mouth (Padule della Trappola - Foce dell'Ombrone) represents one of the last remnants of a complex of wetlands (partly salty and partly freshwater) and sandy dunes, which constituted the pristine landscape of the Tyrrhenian coast. -

The Contribution to Wildlife Conservation of an Italian Recovery

Nature Conservation 44: 1–20 (2021) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.44.65528 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://natureconservation.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity conservation The contribution to wildlife conservation of an Italian Recovery Centre Gabriele Dessalvi1, Enrico Borgo2, Loris Galli1 1 Department of Earth, Environmental and Life Sciences (DISTAV), Genoa University, Corso Europa 26, 16132, Genoa, Italy 2 Museum of Natural History “Giacomo Doria”, Via Brigata Liguria, 9, 16121, Genoa, Italy Corresponding author: Loris Galli ([email protected]) Academic editor: Christoph Knogge | Received 5 March 2021 | Accepted 20 April 2021 | Published 10 May 2021 http://zoobank.org/F5D4BBF2-A839-4435-A1BA-83EAF4BA94A9 Citation: Dessalvi G, Borgo E, Galli L (2021) The contribution to wildlife conservation of an Italian Recovery Centre. Nature Conservation 44: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.44.65528 Abstract Wildlife recovery centres are widespread worldwide and their goal is the rehabilitation of wildlife and the subsequent release of healthy animals to appropriate habitats in the wild. The activity of the Genoese Wild- life Recovery Centre (CRAS) from 2015 to 2020 was analysed to assess its contribution to the conservation of biodiversity and to determine the main factors affecting the survival rate of the most abundant species. In particular, the analyses focused upon the cause, provenance and species of hospitalised animals, the sea- sonal distribution of recoveries and the outcomes of hospitalisation in the different species. In addition, an in-depth analysis of the anthropogenic causes was conducted, with a particular focus on attempts of preda- tion by domestic animals, especially cats.