From Landfill to Marketplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tokyo Sightseeing Route

Mitsubishi UUenoeno ZZoooo Naationaltional Muuseumseum ooff B1B1 R1R1 Marunouchiarunouchi Bldg. Weesternstern Arrtt Mitsubishiitsubishi Buildinguilding B1B1 R1R1 Marunouchi Assakusaakusa Bldg. Gyoko St. Gyoko R4R4 Haanakawadonakawado Tokyo station, a 6-minute walk from the bus Weekends and holidays only Sky Hop Bus stop, is a terminal station with a rich history KITTE of more than 100 years. The “Marunouchi R2R2 Uenoeno Stationtation Seenso-jinso-ji Ekisha” has been designated an Important ● Marunouchi South Exit Cultural Property, and was restored to its UenoUeno Sta.Sta. JR Tokyo Sta. Tokyo Sightseeing original grandeur in 2012. Kaaminarimonminarimon NakamiseSt. AASAHISAHI BBEEREER R3R3 TTOKYOOKYO SSKYTREEKYTREE Sttationation Ueenono Ammeyokoeyoko R2R2 Uenoeno Stationtation JR R2R2 Heeadad Ofccee Weekends and holidays only Ueno Sta. Route Map Showa St. R5R5 Ueenono MMatsuzakayaatsuzakaya There are many attractions at Ueno Park, ● Exit 8 *It is not a HOP BUS (Open deck Bus). including the Tokyo National Museum, as Yuushimashima Teenmangunmangu The shuttle bus services are available for the Sky Hop Bus ticket. well as the National Museum of Western Art. OkachimachiOkachimachi SSta.ta. Nearby is also the popular Yanesen area. It’s Akkihabaraihabara a great spot to walk around old streets while trying out various snacks. Marui Sooccerccer Muuseumseum Exit 4 ● R6R6 (Suuehirochoehirocho) Sumida River Ouurr Shhuttleuttle Buuss Seervicervice HibiyaLine Sta. Ueno Weekday 10:00-20:00 A Marunouchiarunouchi Shuttlehuttle Weekend/Holiday 8:00-20:00 ↑Mukojima R3R3 TOKYOTOKYO SSKYTREEKYTREE TOKYO SKYTREE Sta. Edo St. 4 Front Exit ● Metropolitan Expressway Stationtation TOKYO SKYTREE Kaandanda Shhrinerine 5 Akkihabaraihabara At Solamachi, which also serves as TOKYO Town Asakusa/TOKYO SKYTREE Course 1010 9 8 7 6 SKYTREE’s entrance, you can go shopping R3R3 1111 on the first floor’s Japanese-style “Station RedRed (1 trip 90 min./every 35 min.) Imperial coursecourse Theater Street.” Also don’t miss the fourth floor Weekday Asakusa St. -

Hama-Rikyu Gardens

浜離宮恩賜庭園 庭園リーフレット _ 表面 _ 英語 扉面 裏面 表面 Special Place of Scenic Beauty English /英語 and Special Historic Site For Stamping Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May. Jun. Jul. Aug. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. Hama-rikyu Gardens Special Place of Scenic Beauty ■Garden inauguration April 1, 1946 and Special Historic Site Winter sweet Japanese iris ■Area Hama-rikyu Gardens 250,215.72m2 Plum-blossoms Hydrangea macrophylla ■Hours FLOWER CALENDAR Open from 9am to 5pm Narcissus Chinese Trumpet vine (Entry closed at 4:30pm) ※Closing hour may be extended Hama-rikyu Gardens Rape blossoms Crape myrtle during event period, etc. ■Closed White magnolia Yellow cosmos Year-end holidays(December 29 to January 1) ■Free admission days Yoshino cherry blossoms Cotton rosemallow Green Day (May 4) Hama Palace where sea breeze blows as a reminder of the Edo era. Tokyo Citizen’s Day (October 1) Hana peach Cluster amaryllis ■Guided tour (Free) (Japanese) Double cherry blossoms Cosmos Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays (Twice a day from 11am and 2pm) Japanese wisteria Japanese wax tree (autumnal tints) (English) Mondays 10:30am Peony Maple (autumnal tints) Saturdays 11am ※Starting time may be changed during Rhododendron Ginkgo (yellow leaves) event period, etc. Satsuki azalea 【Contact】 Hama-rikyu Garden Office Tel: 03-3541-0200 Yukitsuri and Fuyugakoi Yukitsuri and Fuyugakoi 1-1 Hamarikyu-teien, Chuo-ku, Tokyo (Winter plant protection) (Winter plant protection) 〒104-0046 ※Bloom time can vary depending on yearly weather conditions etc. Group Annual passport Annual passport Individual (20 or more) (Hama-rikyu Gardens) (Common for 9 gardens) General ¥300 ¥240 ¥1,200 ¥4,000 Admission 65 or over ¥150 ¥120 ¥600 ¥2,000 Elementary school students or under, and junior high students residing or studying in Tokyo are admitted free. -

Auctions and Institutional Integration in the Tsukiji Wholesale Fish Market, Tokyo

Visible Hands: Auctions and Institutional Integration in the Tsukiji Wholesale Fish Market, Tokyo Theodore C. Bestor Working Paper No. 63 Theodore C. Bestor Department of Anthropology Columbia University Mailing Address: Department of Anthropology 452 Schemerhorn Hall Columbia University New York, NY 10027 (212) 854-4571 or 854-6880 FAX: (212) 749-1497 Bitnet: [email protected] Working Paper Series Center on Japanese Economy and Business Graduate School of Business Columbia University September 1992 Visible Hands: Auctions and Institutional Integration in the Tsukiji Wholesale Fish Market, Tokyo Theodore C. Bestor Department of Anthropology and East Asian Institute Columbia University Introduction As an anthropologist specializing in Japanese studies, I am often struck by the uncharacteristic willingness of economists to consider cultural and social factors in their analyses of Japan. Probably the economic system of no society is subject to as much scrutiny, analysis, and sheer speculation regarding its 'special character' as is Japan's. Put another way, emphasis on the special qualities of the Japanese economy suggests a recognition -- implicit or explicit -- that cultural values and social patterns condition economic systems. It remains an open question whether this recognition reflects empirical reality (e.g., perhaps the Japanese economic system is less autonomous than those in other societies) or is an artifact of interpretative conventions (e.g., perhaps both Western and Japanese observers are willing -- if at times antagonistic - partners in ascribing radical 'otherness' to the Japanese economy and therefore are more likely to accord explanatory power to factors that might otherwise be considered exogenous.) Recognition, however, that Japanese economic behavior and institutions are intertwined with and embedded within systems of cultural values and social structural relationships does not imply unanimity of opinion about the significance of this fact. -

Hama-Rikyu Gardens Would Wait for Chance to the Scoop up the Birds with a Net from the Shadows of the Embankment

T h e r e a r e t w o d u c k Duck hunting grounds ● hunting grounds here, 7 Koshindo and Shinsenza. The former was built in 1778, the later in 1791. The ponds and woods of the hunting grounds are surrounded by a three-meter embankment densely planted with Tidal pond with water drawn from Tokyo Bay evergreens and bamboo. That way, ducks could be isolated from the outside and rest easily. Numerous narrow trenches are dug along the pond. Peering from blinds, hunters would use bait such as grasses and seeds to lure the ducks into the trenches. They Hama-rikyu Gardens would wait for chance to the scoop up the birds with a net from the shadows of the embankment. Otsutaibashi bridge & island teahouse on the tidal pond Location ● Hama-Rikyu Teien, Chuo Ward Contact Information ● Hama-rikyu Gardens Administration Office tel: 03-3541-0200 This burial mound was built on (1-1 Hama-rikyu Teien, Chuo-ku 104-0046) Duck mound ● November 5, 1935 to appease the Transport ● Otemon gate: 7-minute walk from Shiodome (Oedo line, Yurikamome line) or Tsukiji-shijo (Oedo line). 12-minute walk from Shinbashi (JR line, Asakusa line, Ginza line). spirits of ducks that were hunted in the gardens. Naka-no-gomon gate: 5-minute walk from Shiodome (Oedo line, Yurikamome line). 15-minute walk from Hamamatsu-cho (JR line). Tokyo Mizube Cruising Line: (Ryogoku↔Hamarikyu↔Odaiba-kaihin-koern) or Water-bus for Asakusa via Hinode-sanbashi pier. Closed ● December 29 to January 1 Otsutaibashi bridge & island teahouse ● Open ● 9 am to 4:30 pm (gates close at 5 pm) Admission ● General: 300 yen, Seniors 65 and older: 150 yen Otsutaibashi bridge connects the shore of the tidal pond with an (Primary school and younger children / Jr. -

Tsukiji 1 Nihonbashi 17 Bldg

14 1 9 7 1 12 13 Minato Bridge Toyomi 16 21 8 1 5 Daiei Inari-jinja Bridge A 9 B 1 Nihonbashi River C Saga (1) Famous waters: Shirokiya well 7 Tokyo Shoken Shrine 18 2 6 4b Pearl Hotel Site of the House of 19 Toyomi Bridge 13 15 10 7 8 Kaikan 7 4 Reigan 10 9 4a Kayabacho Zuiken Kawamura C5 D2 Bridge 2 22 20 Pearl Hotel Yaesu B12 D4 11 21 20 Fukushima B9 COREDO (閉鎖中) 14 C1 Yuraku Bldg. 17 Nakano Bldg. T B10 Kite Museum Kayabacho Kayabacho Sta. Tokyo Metro Tozai Line 2 A4 3 Eitai Bldg. Bridge 11 NihonbashiC1 6 3 12 Chiyoda Bridge 12 Kikaku's house 11 Shinkawa 1 Eitaibashi 7 10 Edobashii-rikkyo(閉鎖中) 12 13 10 A1 B8 C3 C4 C6(閉鎖中)D3 Ohara remains Hotel Villa Fontaine3 Eitai-dori Ave. Eitai Bridge Nihombashi Sta. Overpass 5 Kayabacho B7 B6 D1 15 Inari-jinja Shrine 13 Smile Hotel14 3 A7 A6 8 1 A3 7 Tokyo 8 8 16 7 Chuo Police Office Across 24 Seamen Education 1 B5 Nihombashi 23 Eitai (1) 3 Yumeji Minatoya 3 Shinkawa Daijingu Shrine Shinkawa 30 first31 site 9 14 Nihonbashi Fire Station Tokyo Nihombashi Tower 8 Shinkawa15 Sanko 7 Yukari site Sakamotocho11 Park 6 Shinkawa (1) Shinkawa River Shogenji Tsukiji 1 Nihonbashi 17 Bldg. Sumitomo B0 5 (Redeveloping) 9 remains29 Temple Eitai (2) 13 (Closed) Realty & Development Shinkawa 10 Sta. Nihombashi Kayabacho (2) 2 B4 6 2 2 2 4 Central Commerce School first site 4 9 Map12 usage site remains Community Hall 29 Kabutocho・Kayabacho 16 5 6 4 Shinbabashi 1 6 Kinpai Bldg. -

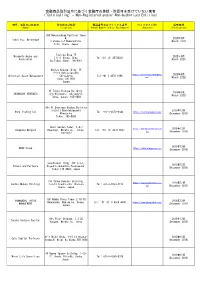

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. 16F Namba Parks Tower 2-10-70 YAMANASHI KYOTO 2019年12月 Nanbanaka, Naniwa-ku, Osaka, Tel: +81 (0) 6-4560-4440 https://www.ykmglobal.com/ MANAGEMENT (December 2019) Japan 8th Floor Shidome, 1.2.20 2019年12月 Tenshi Venture Capital Kaigan, Minatu-ku, Tokyo (December 2019) 6flr Nishi Bldg. -

Hama-Rikyu Gardens

Gardens Shinbashi Oedo line Shinbashi 07 Tsukiji-shijo Tokyo Otemon Shiodome central gate Tsukiji river Yurikamome line wholesale Naka-no- market Asakusa line gomon gate Water bus stop Metoropolitan Expressway No.1 Shiodome river Hama-rikyu Gardens Hamamatsucho Administrator ■ Tokyo Metropolitan Park Association ●Location Hama-Rikyu Teien, Chuo Ward ●Contact Information Hama-rikyu Gardens Administration Office tel: 03-3541-0200 (1-1 Hama-rikyu Teien, Chuo-ku 104-0046) ●Transport Otemon gate: 7-minute walk from Shiodome (Oedo line, Yurikamome line) or Tsukiji-shijo (Oedo line). 12-minute walk from Shinbashi (JR Yamanote line, Asakusa line, Ginza line). Naka-no-gomon gate: 5-minute walk from Shiodome (Oedo line, Yurikamome line). 15-minute walk from Hamamatsu-cho (JR Yamanote line). Tokyo Mizube Cruising Line: (Asakusa (Nitenmon)↔Ryogoku↔Hamarikyu↔Odaiba Marine Park) or Water-bus for Asakusa via Hinode-sanbashi pier. Toll parking facilities available (Available to tour buses and handicapped passengers) *Extra fee is charged to use the water bus dock of Tokyo Mizube Line.. ●Closed December 29 to January 1 ●Open 9 am to 4:30 pm (gates close at 5 pm) ●Admission General: 300 yen, Seniors 65 and older: 150 yen (Primary school and younger children / Jr. high school students living or studying in Tokyo: Free) ●Free days Greenery Day (May 4), Tokyo Citizens Day (October 1) Parking (For tour busses and disabled visitors) Privately operated toll parking lots are also available. This typical Edo era feudal lord’s garden features a tidal pond and Shioiri no Ike Pond two duck hunting grounds. Functioning as an outer fort for Edo castle, the gardens even today retain a castle wall structure. -

Tokyo, So Here Are the Top 100 Favourite Places to Visit and Things to Do in Tokyo

Dive into the flickering neon light of Akihabara, practice tree bathing in Harajuku or live the 50s life in Shinjuku and Shibamata. There are plenty of ideas for a first time visit to Tokyo, So here are the top 100 favourite places to visit and things to do in Tokyo. □ Shibuya Crossing □ Sensō-ji □ Takeshita Street □ Chidorigafuchi Boat □ Ueno Park □ Skytree □ Meiji Shrine □ Tokyo Metropolitan Government □ Robot Restaurant □ Capsule hotel □ Shibamata □ Imperial Palace □ Yanaka Ginza □ Cat Street □ Tokyo Tower □ Takarazuka Revue □ Roppongi Hills □ Todoroki Valley Park □ Ninja Restaurant □ Rainbow Bridge www.travelonthebrain.net □ Kabukiza Theatre □ Ghibli Museum □ Sumo Wrestling □ Book And Bed Tokyo Asakusa □ Day trip to Fuji □ Izakayas in Shinjuku □ Tsukiji □ Mario Go Kart □ Dinner Boat Tour □ Samurai Museum □ Tokyo Disneyland / DisneySea □ Japanese Cooking Class □ Sanja Matsuri □ Samuai Training □ Hello Kitty Puroland □ Ooedo Onsen □ Nakano Broadway □ Pokémon Center □ Anime Japan □ Alice in Wonderland Café □ Calligraphy Lesson □ Edo Tokyo Open Air Museum □ Cat Temple □ Sake Brewery Tour □ Rickshaw Tour □ Wear a kimono □ Daiso □ Harajuku Street Style □ Manga & Anime in Akihabara □ Shinjuku Gyoen □ Maid Café □ Baseball Game □ Tea Ceremony □ Tokyo Station □ Yoyogi Park □ Nezu Museum □ 8Bit Café □ Meguro River □ Odaiba Seaside Park □ Anata no Warehouse □ Bike Tour □ The Yagiri no Watashi □ Nihonbashi/Edo Bridge □ Kawaii Monster Café □ Kameida Tenjin Shrine □ Karaoke □ Eat Blue Ramen □ Shibuya 109 □ Moomin House Café □ Nippori Train Watching -

Welcome to Japan ! Japan Is One of the Most Popular Travel Destinations in the World

Welcome to Japan ! Japan is one of the most popular travel destinations in the world. November is one of the best time to visit Japan, as the weather is relatively dry and mild, and the autumn colors are spectacular in many parts of the country. You can enjoy sightseeing, Japanese culture, shopping and so on. Spot to enjoy within 30 minutes from the symposium venue! Ramen Tsukiji market & Tsukiji Outer market,“SUSHI” “Chukamen” noodles, which Tsukiji market and the Tsukiji outer market is came to Japan from China, have Japan’s leading seafood wholesale market. Food flowered in Japan as a unique You can encounter all of Japan’s traditional Japanese food culture. You can foods such as“SUSHI”. There are also retail enjoy soup, noodles and a variety shops along with numerous restaurants. Japanese of taste stuck to the topping. new culinary trends are born here. Access ▼ 15 minutes subway ride from the Tokyo International Tokyo Ramen Street Forum This is located in the“First Avenue Tokyo Station”, at the Yaesu side of Tokyo Station. This street has eight famous Tokyo ramen shops. ラ ー メ ン 寿 司 築 地 Access ▼ 15 minutes walk from the Tokyo International Forum Ginza & Marunouchi Nakadori Akihabara Ginza & Marunouchi Nakadori Akihabara Electric Town is representative place are one of the top brand-oriented of anime and games, cosplay, idle, etc. This town Shopping streets in Tokyo, which connects has a unique personality. Not only shopping, but Otemachi station and Yurakucho you can enjoy the Japanese pop culture. station. Gathered in the new and Access ▼ 6 minutes JR Line ride from the Yurakucho Station old buildings are various shops and restaurants, from old established shops to new outlets. -

Hama-Rikyu Gardens

浜離宮恩賜庭園 庭園リーフレット _ 表面 _ 英語 扉面 裏面 表面 Special Place of Scenic Beauty English /英語 and Special Historic Site For Stamping Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May. Jun. Jul. Aug. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. Hama-rikyu Gardens Special Place of Scenic Beauty ■Garden inauguration April 1, 1946 and Special Historic Site Winter sweet Japanese iris ■Area Hama-rikyu Gardens 250,215.72m2 Plum-blossoms Hydrangea macrophylla ■Hours FLOWER CALENDAR Open from 9am to 5pm Narcissus Chinese Trumpet vine (Entry closed at 4:30pm) ※Closing hour may be extended Hama-rikyu Gardens Rape blossoms Crape myrtle during event period, etc. ■Closed White magnolia Yellow cosmos Year-end holidays(December 29 to January 1) ■Free admission days Yoshino cherry blossoms Cotton rosemallow Green Day (May 4) Hama Palace where sea breeze blows as a reminder of the Edo era. Tokyo Citizen’s Day (October 1) Hana peach Cluster amaryllis ■Guided tour (Free) (Japanese) Double cherry blossoms Cosmos Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays (Twice a day from 11am and 2pm) Japanese wisteria Japanese wax tree (autumnal tints) (English) Mondays 10:30am Peony Maple (autumnal tints) Saturdays 11am ※Starting time may be changed during Rhododendron Ginkgo (yellow leaves) event period, etc. Satsuki azalea 【Contact】 Hama-rikyu Garden Office Tel: 03-3541-0200 Yukitsuri and Fuyugakoi Yukitsuri and Fuyugakoi 1-1 Hamarikyu-teien, Chuo-ku, Tokyo (Winter plant protection) (Winter plant protection) 〒104-0046 ※Bloom time can vary depending on yearly weather conditions etc. Group Annual passport Annual passport Individual (20 or more) (Hama-rikyu Gardens) (Common for 9 gardens) General ¥300 ¥240 ¥1,200 ¥4,000 Admission 65 or over ¥150 ¥120 ¥600 ¥2,000 Elementary school students or under, and junior high students residing or studying in Tokyo are admitted free. -

New Stage of Nihonbashi Revitalization Plan Initiated Announcement of Vision and Three Priority Initiatives, Including Waterside Regeneration

August 29,2019 For immediate release Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd. Mitsui Fudosan Creating Neighborhoods in Nihonbashi New Stage of Nihonbashi Revitalization Plan Initiated Announcement of Vision and Three Priority Initiatives, Including Waterside Regeneration Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd., a leading global real estate company headquartered in Tokyo, announced today that it has defined a vision for neighborhood renaissance under its Nihonbashi Revitalization Plan along with priority initiatives and a neighborhood renaissance philosophy for the plan’s 3rd Stage. Mitsui Fudosan is currently promoting the Nihonbashi Revitalization Plan, a joint public-private-community initiative on the concept of “Preserving and Revitalizing the Heritage while Creating the Future” that began in 2004 with the opening of COREDO Nihonbashi. The project has promoted the diversification of urban functions and greater urban vitality through mixed-used redevelopment. In the 2nd Stage of the Nihonbashi Revitalization Plan, which began in 2014, Mitsui Fudosan promoted neighborhood renaissance in a way that combines its tangible and intangible aspects in four key areas: creating business clusters, neighborhood renaissance, in harmony with the community and reviving the aquapolis. As a result, the district has diversified its uses and further diversified and internationalized its companies and population, and its former vitality is beginning to return. Now, in 2019, with completion of Nihonbashi Muromachi Mitsui Tower, the Nihonbashi Revitalization Plan enters its 3rd Stage. While continuing to be guided by the concept of “Preserving and Revitalizing the Heritage while Creating the Future” and focus on the four key areas above, in the 3rd Stage, Mitsui Fudosan will promote an open style of neighborhood renaissance that encompasses a broad range of people. -

Lessons Learned from Tokyo Subway Sarin Gas Attack and Countermeasures Against Terrorist Attacks

European Conference of Ministers Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport of Transport Japanese Government 2-3 March 2005 Akasaka Prince Hotel, Tokyo Lessons Learned from Tokyo Subway Sarin Gas Attack and Countermeasures Against Terrorist Attacks Tatsuo FUNATO Tokyo Metro Co., Ltd. Japan LessonsLessons LearnedLearned fromfrom TokyoTokyo SubwaySubway SarinSarin GasGas AttackAttack andand CountermeasuresCountermeasures AgainstAgainst TerroristTerrorist AttacksAttacks TokyoTokyo MetroMetro Co.Co.,,LtdLtd.. SafetySafety AffairsAffairs DepartmentDepartment Rev.H17-3-2 Outline of Tokyo Metro Routes : Ginza Line, Marunouchi Line, Hibiya Line, Tozai Line, Chiyoda Line, Yurakucho Line, Hanzomon Line and Namboku Line, Total operating kilometerage: 183.2 km Number of stations (above ground): 168 (21) Number of passengers per day: 565,590 thousand 67 Sarin Gas Attack • March 20, 1995 ( Monday ) 8:14AM • Occurred on 5 trains, on 3 lines Casualties • Fatalities : 10 passengers, 2 employees • Hospitalized : 960 passengers, 39 employees • Outpatient treatment : 4,446 passengers, 197 employees Total 5,654 persons Outline of the Sarin Gas Attack Method employed in the crime: To prick a bag containing sarin liquid (about 900ml) with the tip of an umbrella *Indiscriminate terrorist attack, using sarin gas, a deadly poison *Occurred within the premises of the subway, a closed space *Sarin gas was dispersed at several locations within a half an hour span Incident site where many people were killed by the use of a resulting in multiple attacks poisonous