Studies of Less Familiar Birds 118. Rock Bunting and Rock Sparrow by P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Data on the Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera) of Passerine Birds in East of Iran

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244484149 New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran ARTICLE · JANUARY 2013 CITATIONS READS 2 142 4 AUTHORS: Behnoush Moodi Mansour Aliabadian Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 3 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS 110 PUBLICATIONS 393 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Ali Moshaverinia Omid Mirshamsi Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 10 PUBLICATIONS 17 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 152 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Omid Mirshamsi Retrieved on: 05 April 2016 Sci Parasitol 14(2):63-68, June 2013 ISSN 1582-1366 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran Behnoush Moodi 1, Mansour Aliabadian 1, Ali Moshaverinia 2, Omid Mirshamsi Kakhki 1 1 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology, Iran. 2 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiology, Iran. Correspondence: Tel. 00985118803786, Fax 00985118763852, E-mail [email protected] Abstract. Lice (Insecta, Phthiraptera) are permanent ectoparasites of birds and mammals. Despite having a rich avifauna in Iran, limited number of studies have been conducted on lice fauna of wild birds in this region. This study was carried out to identify lice species of passerine birds in East of Iran. A total of 106 passerine birds of 37 species were captured. Their bodies were examined for lice infestation. Fifty two birds (49.05%) of 106 captured birds were infested. Overall 465 lice were collected from infested birds and 11 lice species were identified as follow: Brueelia chayanh on Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), B. -

Turkey Birding Eastern Anatolia Th Th 10 June to 20 June 2021 (11 Days)

Turkey Birding Eastern Anatolia th th 10 June to 20 June 2021 (11 days) Caspian Snowcock by Alihan Vergiliel Turkey, a country the size of Texas, is a spectacular avian and cultural crossroads. This fascinating nation boasts an ancient history, from even before centuries of Greek Roman and Byzantine domination, through the 500-year Ottoman Empire and into the modern era. Needless to say, with such a pedigree the country holds some very impressive archaeological and cultural sites. Our tour of Eastern Turkey starts in the eastern city of Van, formerly known as Tuspa and 3,000 years ago the capital city of the Urartians. Today there are historical structures from the Seljuk and Ottoman periods, and Urartian artifacts can be seen at its archaeological museum. RBL Turkey Itinerary 2 However, it is the birds that are of primary interest to us as here, at the eastern limits of the Western Palearctic, we expect to find some very special and seldom-seen species, including Mountain ‘Caucasian’ Chiffchaff, Green Warbler, Mongolian Finch and Grey-headed Bunting. Around the shores of Lake Van we will seek out Moustached and Paddyfield Warblers in the dense reed beds, while on the lake itself, our targets include Marbled Teal, the threatened White-headed Duck, Dalmatian Pelican, Pygmy Cormorant and Armenian Gull, plus a selection of waders that may include Terek and Broad-billed Sandpiper. As we move further north-east into the steppe and semi desert areas, we will attempt to find Great Bustards and Demoiselle Cranes, with a potential supporting cast of Montagu’s Harrier, Steppe Eagle, the exquisite Citrine Wagtail and Twite, to name but a few. -

Lhasa and the Tibetan Plateau Cumulative

Lhasa and the Tibetan Plateau Cumulative Bird List Column A: Total number of tours (out of 6) that the species was recorded Column B: Total number of days that the species was recorded on the 2016 tour Column C: Maximum daily count for that particular species on the 2016 tour Column D: H = Heard Only; (H) = Heard more than seen Globally threatened species as defined by BirdLife International (2004) Threatened birds of the world 2004 CD-Rom Cambridge, U.K. BirdLife International are identified as follows: EN = Endangered; VU = Vulnerable; NT = Near- threatened. A B C D 6 Greylag Goose 2 15 Anser anser 6 Bar-headed Goose 4 300 Anser indicus 3 Whooper Swan 1 2 Cygnus cygnus 1 Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna 6 Ruddy Shelduck 8 700 Tadorna ferruginea 3 Gadwall 2 3 Anas strepera 1 Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope 5 Mallard 2 8 Anas platyrhynchos 2 Eastern Spot-billed Duck Anas zonorhyncha 1 Indian or Eastern Spot-billed Duck Anas poecilorhynchos or A. zonorhyncha 1 Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata 1 Northern Pintail Anas acuta 1 Garganey 2 15 Anas querquedula 4 Eurasian Teal 2 50 Anas crecca 6 Red-crested Pochard 3 2000 Netta rufina 6 Common Pochard 2 200 Aythya ferina 3 Ferruginous Duck NT 1 8 Aythya nyroca 6 Tufted Duck 2 200 Aythya fuligula 5 Common Goldeneye 2 11 Bucephala clangula 4 Common Merganser 3 51 Mergus merganser 5 Chinese Grouse NT 2 1 Tetrastes sewerzowi 4 Verreaux's Monal-Partridge 1 1 H Tetraophasis obscurus 5 Tibetan Snowcock 1 5 H Tetraogallus tibetanus 4 Przevalski's Partridge 1 1 Alectoris magna 1 Daurian Partridge Perdix dauurica 6 Tibetan Partridge 2 11 Perdix hodgsoniae ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. -

Southern Israel: a Spring Migration Spectacular

SOUTHERN ISRAEL: A SPRING MIGRATION SPECTACULAR MARCH 21–APRIL 3, 2019 Spectacular male Bluethroat (orange spotted form) in one of the world’s greatest migration hotspots, Eilat © Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & MEIDAD GOREN LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SOUTHERN ISRAEL: A SPRING MIGRATION SPECTACULAR March 21–April 3, 2019 By Andrew Whittaker The sky was full of migrating White Storks in the thousands above Masada and parts of the the Negev Desert © Andrew Whittaker My return to Israel after working in Eilat banding birds some 36 years ago certainly was an exciting prospect and a true delight to witness, once again, one of the world’s most amazing natural phenomena, avian migration en masse. This delightful tiny country is rightly world-renowned as being the top migration hotspot, with a staggering estimated 500–750 million birds streaming through the African- Eurasian Flyway each spring, comprising over 200 different species! Israel is truly an unparalleled destination allowing one to enjoy this exceptional spectacle, especially in the spring when all are in such snazzy breeding plumage. Following the famous Great Rift Valley that bisects Israel, they migrate thousands of miles northwards from their wintering grounds in western Africa bound for rich breeding grounds, principally in central and eastern Europe. Israel acts as an amazing bottleneck resulting in an avian abundance everywhere you look: skies filled with countless migratory birds from storks to raptors; Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Southern Israel, 2019 rich fish ponds and salt flats holding throngs of flamingos, shorebirds, and more; and captivating deserts home to magical regional goodies such as sandgrouse, bustards and larks, while every bush and tree are moving with warblers. -

The Evolution of Ancestral and Species-Specific Adaptations in Snowfinches at the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

The evolution of ancestral and species-specific adaptations in snowfinches at the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Yanhua Qua,1,2, Chunhai Chenb,1, Xiumin Chena,1, Yan Haoa,c,1, Huishang Shea,c, Mengxia Wanga,c, Per G. P. Ericsond, Haiyan Lina, Tianlong Caia, Gang Songa, Chenxi Jiaa, Chunyan Chena, Hailin Zhangb, Jiang Lib, Liping Liangb, Tianyu Wub, Jinyang Zhaob, Qiang Gaob, Guojie Zhange,f,g,h, Weiwei Zhaia,g, Chi Zhangb,2, Yong E. Zhanga,c,g,i,2, and Fumin Leia,c,g,2 aKey Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100101 Beijing, China; bBGI Genomics, BGI-Shenzhen, 518084 Shenzhen, China; cCollege of Life Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China; dDepartment of Bioinformatics and Genetics, Swedish Museum of Natural History, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden; eBGI-Shenzhen, 518083 Shenzhen, China; fState Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 650223 Kunming, China; gCenter for Excellence in Animal Evolution and Genetics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 650223 Kunming, China; hSection for Ecology and Evolution, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; and iChinese Institute for Brain Research, 102206 Beijing, China Edited by Nils Chr. Stenseth, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, and approved February 24, 2021 (received for review June 16, 2020) Species in a shared environment tend to evolve similar adapta- one of the few avian clades that have experienced an “in situ” tions under the influence of their phylogenetic context. Using radiation in extreme high-elevation environments, i.e., higher snowfinches, a monophyletic group of passerine birds (Passer- than 3,500 m above sea level (m a.s.l.) (17, 18). -

Signalling in Male but Not in Female Eurasian Tree Sparrows Passer

Received Date : 16-Feb-2016 Revised Date : 09-Oct-2016 Accepted Date : 11-Oct-2016 Article type : Original Paper Editor : Eivin Roskaft Running head: Sex difference in signalling by throat patch in tree sparrow Status badge-signalling in male but not in female Eurasian Tree Sparrows Passer montanus FERENC MÓNUS,1,2* ANDRÁS LIKER,3 ZSOLT PÉNZES4 & ZOLTÁN BARTA2 Article 1Institute of Biology, University of Nyíregyháza, Sóstói út 2-4., 4400 Nyíregyháza, Hungary 2MTA-DE ‘Lendület’ Behavioural Ecology Research Group, Department of Evolutionary Zoology, University of Debrecen, Egyetemtér 1., 4032 Debrecen, Hungary 3Department of Limnology, University of Pannonia, P.O. Box 158, 8201 Veszprém, Hungary 4Department of Ecology, University of Szeged, Középfasor 52., 6726 Szeged, Hungary and Institute of Genetics, Biological Research Center, Temesvári krt. 62, 6726 Szeged, Hungary *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Male ornaments, such as plumage coloration, frequently serve as signals. The signalling function of similar ornaments in females has, however, received much less attention despite the fact that conspicuousness of their ornaments is often comparable to those of males. In this study we tested the signalling function of a plumage trait present in both sexes in the Eurasian Tree Sparrow Passer montanus. The black throat patch has been repeatedly found to have a signal function in the closely This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been Accepted through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/ibi.12425 This article is protected by copyright. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

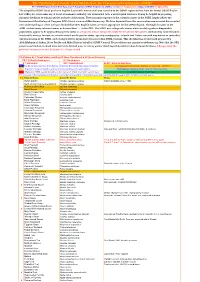

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Proving: Sparrow (Passer Domesticus) Date: October 2004 by Misha Norland, Peter Fraser & the School of Homeopathy

Orchard Leigh · Rodborough Hill · Stroud · Gloucestershire · England · GL5 3SS T: +44 (0)1453 765 956 · F: +44 (0)1453 765 953 · E: [email protected] www.alternative-training.com Proving: Sparrow (Passer Domesticus) Date: October 2004 By Misha Norland, Peter Fraser & The School of Homeopathy. Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Clade: Dinosauria Class: Aves Order: Passeriformes Suborder: Passeri Infraorder: Passerida Superfamily: Passeroidea Family: Passeridae Illiger, 1811 Latin Name: Passer Domesticus Source /Description & Habitat The sparrow is part of a small family of birds called passerine birds, Passeridae. They can also be known as true sparrows, old world sparrow. Many of the sparrow species nest in buildings, the House and Eurasian tree sparrow inhabit cities in larges numbers. The sparrow is primarily a seedeater but can also consume small insects. Sparrows are generally small brown- grey birds with short tails and small powerful beaks. There are only subtle differences between each of the species. Sparrows look very similar to other seed eating birds such as finches. Sparrows have a vestigial dorsal on their outer primary feather and has an extra bone in their tongue, which helps to stiffen the tongue when holding seeds. They also have specialised bills and elongated alimentary canals for eating seeds. Taxonomy In the book ‘Handbook the Birds of the World’ the classification for the main groups of the sparrow, is the true sparrow (passer), snow finches (montifringilla) and the rock sparrow (petronia). The groups are similar to each other and each is fairly homogeneous. Early classifications place the sparrow as close relatives of the weavers among various families of small seed eating birds, based on their breeding behaviour, bill structure and moult. -

Arabian Peninsula

THE CONSERVATION STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE BREEDING BIRDS OF THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Compiled by Andy Symes, Joe Taylor, David Mallon, Richard Porter, Chenay Simms and Kevin Budd ARABIAN PENINSULA The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM - Regional Assessment About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature-based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with almost 1,300 government and NGO Members and more than 15,000 volunteer experts in 185 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by almost 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of around 7,500 experts. SSC advises IUCN and its members on the wide range of technical and scientific aspects of species conservation, and is dedicated to securing a future for biodiversity. SSC has significant input into the international agreements dealing with biodiversity conservation. About BirdLife International BirdLife International is the world’s largest nature conservation Partnership. BirdLife is widely recognised as the world leader in bird conservation. -

Israel Tour Report 2018

ISRAEL 14–24 April 2018 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Israel 2018 www.birdquest-tours.com Harlequin Duck (drake), Laxá. Sinai Rosefinch, male, Mizpe Ramon. Cover: Corn Crake, Ofira Park, Eilat (Mike Watson). 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Israel 2018 www.birdquest-tours.com Returning to Israel for the first time in almost seek in one of the last acacia-filled wadis in 30 years was an exciting prospect. It was the Arava Valley, rose pink male Sinai Rose- once my favourite destination and was one of finches drinking at a spring on the Dead Sea the first places I birded outside the UK back escarpment, smart Desert Finches around in the 1980s. The bird-show is as good as it our vehicle at Sde Boker and Syrian Serins ever was and in some ways even better with song-flighting over us on Mount Hermon. more information available and new sites Numerous other notable encounters included discovered or created in this period. We had Marbled Teals seen by golf cart at Lake Ag- a great time on a short itinerary, which visit- amon in the Hula Valley, lots of Chukar and ed the north, including Ma’agan Mikael, Bet Sand Partridges, Pygmy Cormorants common She’an Valley, Hula, Mount Hermon and the at Ma’agan Mikael, the endangered Egyptian Golan Heights before heading south via the Vulture, Levant Sparrowhawks on migration, Dead Sea to Eilat and then completing a cir- great views of both Little and Spotted Crakes, cle back to Tel Aviv via the Negev Desert. We at least 28 White-eyed Gulls from Eilat’s fa- recorded 230 species, including many region- mous north beach, -

Rock Sparrow: New to Britain and Ireland

British Birds VOLUME 76 NUMBER 6 JUNE 1983 Rock Sparrow: new to Britain and Ireland S.J. M. Gantlett andR. G. Millington At 08.00 GMT on 14th June 1981, we were walking from the 'North Z^.Hide' at Cley, Norfolk, towards the Coastguard's carpark. RGM idly lifted his binoculars to look at a couple of small birds feeding on the ground under the Eye Field fence. Without speaking, he intimated that it might be worthwhile for SJMG also to raise his binoculars. [Brit. Birds 76: 245-247,June 1983] 245 246 Rock Sparrow: new to Britain and Ireland 97. Rock Sparrow Petronia petronia, Spain, May 1961 (Arthur Gilpin) One of the birds was a male Linnet Carduelis cannabina, but the other was a sparrow-like bird with a boldly striped head. The initial thoughts that it might be a Lapland Bunting Calcarius lapponicus were quickly superseded by thoughts of Nearctic sparrows and various rare buntings. RGM then suggested that it might be a Rock Sparrow Petronia petronia. At this point, the bird flitted up onto the fence, exhibiting a shortish dark tail tipped with prominent white spots, which confirmed the identification for SJMG, who was familiar with Rock Sparrow in Europe. For the next ten minutes, we watched the bird, at ranges of about 50- 100m, as it fed along the ruts in the turfed gravel strip between the beach and the field. If flitted up onto the fence a few times and we both compiled detailed descriptions. SJMG then left to alert other observers: J. McLaughlin, M. -

Bird Watching Tour in Mongolia 2019

Mongolia 18 May – 09 June 2019 Bart De Keersmaecker, Daniel Hinckley, Filip Bogaert, Joost Mertens, Mark Van Mierlo, Miguel Demeulemeester and Paul De Potter Leader: Bolormunkh Erdenekhuu male Black-billed Capercaillie – east of Terelj, Mongolia Report by: Bart, Mark, Miguel, Bogi Pictures: everyone contributed 2 Introduction In 3 weeks, tour we recorded staggering 295 species of birds, which is unprecedented by similar tours!!! Many thanks to Wouter Faveyts, who had to bail out because of work related matters, but was a big inspiration while planning the trip. The Starling team, especially Johannes Jansen for careful planning and adjusting matters to our needs. Last but not the least Bolormunkh aka Bogi and his crew of dedicated people. The really did their utmost best to make this trip one of the best ever. Intinerary Day 1. 18th May Arrival 1st group at Ulaanbaatar. Birding along the riparian forest of Tuul river Day 2. 19th May Arrival 2nd part of group. Drive to Dalanzadgad Day 3. 20th May Dalanzadgad area Day 4. 21st May Shivee Am and Yolyn Am Gorges Day 5. 22nd May Yolyn Am Gorge, to Khongoryn Els Day 6. 23rd May Khongoryn Els and Orog Nuur Day 7. 24th May Orog Nuur, Bogd and Kholbooj Nuur Day 8. 25th May Kholbooj Nuur Day 9. 26th May Kholbooj Nuur and drive to Khangai mountain Day 10. 27th May Khangai mountain, drive to Tuin River Day 11. 28th May Khangai mountain drive to Orkhon River Day 12. 29th May Taiga forest Övörhangay and Arhangay Day 13. 30th May Khangai taiga forest site 2 Day 14.