Nevada Bat Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listed Species Management Plan

ASHTON PLACE (F.K.A. ORANGE RIVER 130) LISTED SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN April 2021 Prepared For: 11400 Orange River LLC 2970 Luckie Road Westin, Florida 33331 (305) 992-8467 Prepared By: Passarella & Associates, Inc. 13620 Metropolis Avenue, Suite 200 Fort Myers, Florida 33912 (239) 274-0067 Project No. 20ORL3287 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Lee County Protected Species Survey ............................................................................... 1 3.0 Site Plan ............................................................................................................................. 2 4.0 Florida Pine Snake Management Plan .............................................................................. 3 4.1 Biology ................................................................................................................... 3 4.2 Management Plan................................................................................................... 3 5.0 Wood Stork and Listed Wading Bird Management Plan................................................... 3 5.1 Management Plan................................................................................................... 4 6.0 Least Tern Management Plan ............................................................................................ 4 7.0 Florida Black Bear Management Plan .............................................................................. -

Do We Need to Use Bats As Bioindicators?

biology Perspective Do We Need to Use Bats as Bioindicators? Danilo Russo * , Valeria B. Salinas-Ramos , Luca Cistrone, Sonia Smeraldo, Luciano Bosso * and Leonardo Ancillotto Wildlife Research Unit, Dipartimento di Agraria, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Via Università, 100, 80055 Portici, Italy; [email protected] (V.B.S.-R.); [email protected] (L.C.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (L.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.R.); [email protected] (L.B.) Simple Summary: Bioindicators are organisms that react to the quality or characteristics of the environment and their changes. They are vitally important to track environmental alterations and take action to mitigate them. As choosing the right bioindicators has important policy implications, it is crucial to select them to tackle clear goals rather than selling specific organisms as bioindicators for other reasons, such as for improving their public profile and encourage species conservation. Bats are a species-rich mammal group that provide key services such as pest suppression, pollination of plants of economic importance or seed dispersal. Bats show clear reactions to environmental alterations and as such have been proposed as potentially useful bioindicators. Based on the rel- atively limited number of studies available, bats are likely excellent indicators in habitats such as rivers, forests, and urban sites. However, more testing across broad geographic areas is needed, and establishing research networks is fundamental to reach this goal. Some limitations to using bats as bioindicators exist, such as difficulties in separating cryptic species and identifying bats in flight from their calls. -

33245 02 Inside Front Cover

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU 186 BATS OF RAVENNA VOL. 106 Bats of Ravenna Training and Logistics Site, Portage and Trumbull Counties, Ohio1 VIRGIL BRACK, JR.2 AND JASON A. DUFFEY, Center for North American Bat Research and Conservation, Department of Ecology and Organismal Biology, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47089; Environmental Solutions & Innovations, Inc., 781 Neeb Road, Cincinnati, OH 45233 ABSTRACT. Six species of bats (n = 272) were caught at Ravenna Training and Logistics Site during summer 2004: 122 big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus), 100 little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus), 26 red bats (Lasiurus borealis), 19 northern myotis (Myotis septentrionalis), three hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus), and two eastern pipistrelles (Pipistrellus subflavus). Catch was 9.7 bats/net site (SD = 10.2) and 2.4 bats/net night (SD = 2.6). No bats were captured at two net sites and only one bat was caught at one site; the largest captures were 33, 36, and 37 individuals. Five of six species were caught at two sites, 2.7 (SD = 1.4) species were caught per net site, and MacArthur’s diversity index was 2.88. Evidence of reproduction was obtained for all species. Chi-square tests indicated no difference in catch of males and reproductive females in any species or all species combined. Evidence was found of two maternity colonies each of big brown bats and little brown myotis. Capture of big brown bats (X2 = 53.738; P <0.001), little brown myotis (X2 = 21.900; P <0.001), and all species combined (X2 = 49.066; P <0.001) was greatest 1 – 2 hours after sunset. -

Bat Distribution in the Forested Region of Northwestern California

BAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE FORESTED REGION OF NORTHWESTERN CALIFORNIA Prepared by: Prepared for: Elizabeth D. Pierson, Ph.D. California Department of Fish and Game William E. Rainey, Ph.D. Wildlife Management Division 2556 Hilgard Avenue Non Game Bird and Mammal Section Berkeley, CA 9470 1416 Ninth Street (510) 845-5313 Sacramento, CA 95814 (510) 548-8528 FAX [email protected] Contract #FG-5123-WM November 2007 Pierson and Rainey – Forest Bats of Northwestern California 2 Pierson and Rainey – Forest Bats of Northwestern California 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bat surveys were conducted in 1997 in the forested regions of northwestern California. Based on museum and literature records, seventeen species were known to occur in this region. All seventeen were identified during this study: fourteen by capture and release, and three by acoustic detection only (Euderma maculatum, Eumops perotis, and Lasiurus blossevillii). Mist-netting was conducted at nineteen sites in a six county area. There were marked differences among sites both in the number of individuals captured per unit effort and the number of species encountered. The five most frequently encountered species in net captures were: Myotis yumanensis, Lasionycteris noctivagans, Myotis lucifugus, Eptesicus fuscus, and Myotis californicus; the five least common were Pipistrellus hesperus, Myotis volans, Lasiurus cinereus, Myotis ciliolabrum, and Tadarida brasiliensis. Twelve species were confirmed as having reproductive populations in the study area. Sampling sites were assigned to a habitat class: young growth (YG), multi-age stand (MA), old growth (OG), and rock dominated (RK). There was a significant response to habitat class for the number of bats captured, and a trend towards differences for number of species detected. -

On the Distribution, Taxonomy and Karyology of the Genus Plecotus

TurkJZool 27(2003)293-300 ©TÜB‹TAK OntheDistribution,TaxonomyandKaryologyoftheGenus Plecotus (Chiroptera:Vespertilionidae)inTurkey AhmetKARATAfi DepartmentofBiology,FacultyofScience-Art,Ni¤deUniversity,Ni¤de–TURKEY NuriY‹⁄‹T,ErcümentÇOLAK,TolgaKANKILIÇ DepartmentofBiology,FacultyofScience,AnkaraUniversity,Ankara-TURKEY Received:12.04.2002 Abstract: Plecotusauritus andPlecotusaustriacus wererecordedfrom8and3localitiesintheAsiaticpartofTurkey,respectively. Itwasdeterminedthatthelengthofthefirstpremolar,theshapeofthezygomaticarchesandbaculumdistinguishthesetaxaf rom eachother.Apartfromthesemorphologicalcharacteristics,thetibialengthof P.austriacus wasfoundtobesignificantlygreater thanthatof P.austriacus (P<0.05).Thediploidchromosomenumberswereidenticalinbothtaxa(2n=32).Thenumberof chromosomalarms(FN=54)andthenumberofautosomalchromosomalarms(FNa=50)werethesameasinpreviouslypublished papersonP.austriacus. KeyWords: Plecotusauritus,Plecotusaustriacus,Karyology,Turkey Türkiye’deYay›l›flGösterenPlecotus (Chiroptera:Vespertilionidae)CinsininYay›l›fl›, TaksonomisiveKaryolojisiÜzerineBirÇal›flma Özet: Plecotusauritus sekizvePlecotusaustriacus üçlokalitedenolmaküzereAnadolu’dankaydedildi.‹lkpremolarlar›nuzunlu¤u, zygomatikyay›nvebakulumunfleklininbutaksonlar›birbirindenay›rd›¤›saptand›.Bumorfolojikkarakterlerdenbaflka, P. autriacus’untibiauzunlu¤ununP.austriacus’tanistatistikiolarakdahabüyükoldu¤ubelirlendi(P<0.05).Diploidkromozomsay›s› herikitaksondabenzerbirflekilde2n=32dir. P.austriacus’unkromozomkolsay›lar›n›n(FN=54)veotosomalkromozomkol say›lar›n›n(FNa=50)literatüreuygunoldu¤ubulundu. -

Forest Management and Bats

F orest Management a n d B a t s | 1 Forest Management and Bats F orest Management a n d B a t s | 2 Bat Basics More than 1,400 species of bats account for almost a quarter of all mammal species worldwide. Bats are exceptionally vulnerable to population losses, in part because they are one of the slowest-reproducing mammals on Earth for their size, with most producing only one young each year. For their size, bats are among the world’s longest-lived mammals. The little brown bat can live up to 34 years in the wild. Contrary to popular misconceptions, bats are not blind and do not become entangled in human hair. Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. Most bat species use an extremely sophisticated biological sonar, called echolocation, to navigate and hunt for food. Some bats can detect an object as fine as a human hair in total darkness. Worldwide, bats are a primary predator of night-flying Merlin Tuttle insects. A single little brown bat, a resident of North American forests, can consume 1,000 mosquito-sized insects in just one hour. All but three of the 47 species of bats found in the United States and Canada feed solely on insects, including many destructive agricultural pests. The remaining bat species feed on nectar, pollen, and the fruit of cacti and agaves and play an important role in pollination and seed dispersal in southwestern deserts. The 15 million Mexican free-tailed bats at Bracken Cave, Texas, consume approximately 200 tons of insects nightly. -

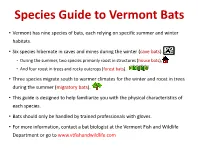

Nine Species of Bats, Each Relying on Specific Summer and Winter Habitats

Species Guide to Vermont Bats • Vermont has nine species of bats, each relying on specific summer and winter habitats. • Six species hibernate in caves and mines during the winter (cave bats). • During the summer, two species primarily roost in structures (house bats), • And four roost in trees and rocky outcrops (forest bats). • Three species migrate south to warmer climates for the winter and roost in trees during the summer (migratory bats). • This guide is designed to help familiarize you with the physical characteristics of each species. • Bats should only be handled by trained professionals with gloves. • For more information, contact a bat biologist at the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department or go to www.vtfishandwildlife.com Vermont’s Nine Species of Bats Cave Bats Migratory Tree Bats Eastern small-footed bat Silver-haired bat State Threatened Big brown bat Northern long-eared bat Indiana bat Federally Threatened State Endangered J Chenger Federally and State J Kiser Endangered J Kiser Hoary bat Little brown bat Tri-colored bat Eastern red bat State State Endangered Endangered Bat Anatomy Dr. J. Scott Altenbach http://jhupressblog.com House Bats Big brown bat Little brown bat These are the two bat species that are most commonly found in Vermont buildings. The little brown bat is state endangered, so care must be used to safely exclude unwanted bats from buildings. Follow the best management practices found at www.vtfishandwildlife.com/wildlife_bats.cfm House Bats Big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus Big thick muzzle Weight 13-25 g Total Length (with Tail) 106 – 127 mm Long silky Wingspan 32 – 35 cm fur Forearm 45 – 48 mm Description • Long, glossy brown fur • Belly paler than back • Black wings • Big thick muzzle • Keeled calcar Similar Species Little brown bat is much Commonly found in houses smaller & lacks keeled calcar. -

Yuma Myotis Myotis Yumanensis

Wyoming Species Account Yuma Myotis Myotis yumanensis REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: No special status USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Nongame Wildlife CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS4 (Cb), Tier III WYNDD: G5, S1 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Yuma Myotis (Myotis yumanensis) has no additional regulatory status or conservation rank considerations beyond those listed above. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are six recognized subspecies of Yuma Myotis 1. Because of distributional uncertainties, it is unclear which subspecies occur in Wyoming. In general, the subspecies M. y. yumanensis occurs in the southern Rocky Mountains, while M. y. sociabilis occurs in the northern Rocky Mountains 1, 2. Description: Yuma Myotis may be difficult to identify in the field, even by skilled observers. The species is a small vespertilionid bat, but medium in size among bats in the genus Myotis. Pelage color is variable across the species’ range. Dorsal fur is short, dull, and varies from gray and brown to pale tan in color. Ventral fur is lighter in color, white or buffy. The ears, wing, and tail membranes are pale brown to gray 1. Males and females are identical in appearance, but females may be significantly larger than males in some populations 1. Juveniles are similar in appearance but can be differentiated from adults by the lack of ossified joints in the phalanges for the first summer 3, 4. Yuma Myotis is similar in appearance to other co-occurring Myotis species. Yuma Myotis can be distinguished from Long-legged Myotis (M. -

SFSC Search Down to 4

C M Y K www.newssun.com EWS UN NHighlands County’s Hometown-S Newspaper Since 1927 Rivalry rout Deadly wreck in Polk Harris leads Lake 20-year-old woman from Lake Placid to shutout of AP Placid killed in Polk crash SPORTS, B1 PAGE A2 PAGE B14 Friday-Saturday, March 22-23, 2013 www.newssun.com Volume 94/Number 35 | 50 cents Forecast Fire destroys Partly sunny and portable at Fred pleasant High Low Wild Elementary Fire alarms “Myself, Mr. (Wally) 81 62 Cox and other administra- Complete Forecast went off at 2:40 tors were all called about PAGE A14 a.m. Wednesday 3 a.m.,” Waldron said Wednesday morning. Online By SAMANTHA GHOLAR Upon Waldron’s arrival, [email protected] the Sebring Fire SEBRING — Department along with Investigations into a fire DeSoto City Fire early Wednesday morning Department, West Sebring on the Fred Wild Volunteer Fire Department Question: Do you Elementary School cam- and Sebring Police pus are under way. Department were all on think the U.S. govern- The school’s fire alarms the scene. ment would ever News-Sun photo by KATARA SIMMONS Rhoda Ross reads to youngsters Linda Saraniti (from left), Chyanne Carroll and Camdon began going off at approx- State Fire Marshal seize money from pri- Carroll on Wednesday afternoon at the Lake Placid Public Library. Ross was reading from imately 2:40 a.m. and con- investigator Raymond vate bank accounts a children’s book she wrote and illustrated called ‘A Wildflower for all Seasons.’ tinued until about 3 a.m., Miles Davis was on the like is being consid- according to FWE scene for a large part of ered in Cyprus? Principal Laura Waldron. -

Venus in Two Acts Saidiya Hartman

Venus in Two Acts Saidiya Hartman Small Axe, Number 26 (Volume 12, Number 2), June 2008, pp. 1-14 (Article) Published by Duke University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/241115 Access provided by University Of Maryland @ College Park (13 Mar 2017 20:04 GMT) Venus in Two Acts Saidiya Hartman ABSTR A CT : This essay examines the ubiquitous presence of Venus in the archive of Atlantic slavery and wrestles with the impossibility of discovering anything about her that hasn’t already been stated. As an emblematic figure of the enslaved woman in the Atlantic world, Venus makes plain the convergence of terror and pleasure in the libidinal economy of slavery and, as well, the intimacy of history with the scandal and excess of literature. In writing at the limit of the unspeak- able and the unknown, the essay mimes the violence of the archive and attempts to redress it by describing as fully as possible the conditions that determine the appearance of Venus and that dictate her silence. In this incarnation, she appears in the archive of slavery as a dead girl named in a legal indict- ment against a slave ship captain tried for the murder of two Negro girls. But we could have as easily encountered her in a ship’s ledger in the tally of debits; or in an overseer’s journal—“last night I laid with Dido on the ground”; or as an amorous bed-fellow with a purse so elastic “that it will contain the largest thing any gentleman can present her with” in Harris’s List of Covent- Garden Ladies; or as the paramour in the narrative of a mercenary soldier in Surinam; or as a brothel owner in a traveler’s account of the prostitutes of Barbados; or as a minor character in a nineteenth-century pornographic novel.1 Variously named Harriot, Phibba, Sara, Joanna, Rachel, Linda, and Sally, she is found everywhere in the Atlantic world. -

Corynorhinus Townsendii): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project October 25, 2006 Jeffery C. Gruver1 and Douglas A. Keinath2 with life cycle model by Dave McDonald3 and Takeshi Ise3 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada 2Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Old Biochemistry Bldg, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82070 3Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3166, Laramie, WY 82071 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Gruver, J.C. and D.A. Keinath (2006, October 25). Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/townsendsbigearedbat.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the modeling expertise of Dr. Dave McDonald and Takeshi Ise, who constructed the life-cycle analysis. Additional thanks are extended to the staff of the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for technical assistance with GIS and general support. Finally, we extend sincere thanks to Gary Patton for his editorial guidance and patience. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Jeff Gruver, formerly with the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Biological Sciences program at the University of Calgary where he is investigating the physiological ecology of bats in northern arid climates. He has been involved in bat research for over 8 years in the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains, and the Badlands of southern Alberta. He earned a B.S. in Economics (1993) from Penn State University and an M.S. -

Appendix B References

Final Tier 1 Environmental Impact Statement and Preliminary Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix B, References July 2021 Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S ADOT Project No. 999 SW 0 M5180 01P I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 This page intentionally left blank. July 2021 Project No. M5180 01P / Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 ADEQ. 2002. Groundwater Protection in Arizona: An Assessment of Groundwater Quality and 2 the Effectiveness of Groundwater Programs A.R.S. §49-249. Arizona Department of 3 Environmental Quality. 4 ADEQ. 2008. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Pinal Active Management Area: A 2005-2006 5 Baseline Study. Open File Report 08-01. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Water 6 Quality Division, Phoenix, Arizona. June 2008. 7 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/pinal_ofr.pdf. 8 ADEQ. 2011. Arizona State Implementation Plan: Regional Haze Under Section 308 of the 9 Federal Regional Haze Rule. Air Quality Division, Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, 10 Phoenix, Arizona. January 2011. https://www.resolutionmineeis.us/documents/adeq-sip- 11 regional-haze-2011. 12 ADEQ. 2013a. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Upper Hassayampa Basin: A 2003-2009 13 Baseline Study. Open File Report 13-03, Phoenix: Water Quality Division. 14 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/upper_hassayampa.pdf. 15 ADEQ. 2013b. Arizona Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Fact Sheet: Construction 16 General Permit for Stormwater Discharges Associated with Construction Activity. Arizona 17 Department of Environmental Quality. June 3, 2013. 18 https://static.azdeq.gov/permits/azpdes/cgp_fact_sheet_2013.pdf.