Magnetic Resonance Imaging Is Useful for Diagnosis of Sacral Insufficiency Fracture and Target Identification in Sacroplasty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer-Assisted System in Stress Radiography for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury with Correspondent Evaluation of Relevant Diagnostic Factors

diagnostics Article Computer-Assisted System in Stress Radiography for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury with Correspondent Evaluation of Relevant Diagnostic Factors Chien-Kuo Wang 1, Liang-Ching Lin 2, Yung-Nien Sun 3, Cheng-Shih Lai 1, Chia-Hui Chen 4,* and Cheng-Yi Kao 1,* 1 Department of Medical Imaging, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, No. 1 University Rd, Tainan 704, Taiwan; [email protected] (C.-K.W.); [email protected] (C.-S.L.) 2 Department of Statistics, National Cheng Kung University, No. 1 University Rd, Tainan 704, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Cheng Kung University, No. 1 University Rd, Tainan 704, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 Department of Medical Imaging and Radiological Sciences, I-Shou University, No.8, Yida Rd., Jiaosu Village, Yanchao District, Kaohsiung City 82445, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.-H.C.); [email protected] (C.-Y.K.); Tel.: +886-7-6151100#7802 (C.-H.C.); +886-6-2766108 (C.-Y.K.); Fax: +886-7-6155150 (C.-H.C.); +886-6-2766608 (C.-Y.K.) Abstract: We sought to design a computer-assisted system measuring the anterior tibial translation in stress radiography, evaluate its diagnostic performance for an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear, and assess factors affecting the diagnostic accuracy. Retrospective research for patients with both Citation: Wang, C.-K.; Lin, L.-C.; knee stress radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at our institution was performed. A Sun, Y.-N.; Lai, C.-S.; Chen, C.-H.; complete ACL rupture was confirmed on an MRI. -

Bulletin FEBRUARY 2013

ISSUE 51- 52 Bulletin FEBRUARY 2013 Kaohsiung Exhibition & Convention Center BANGKOK BEIJING HONG KONG SHANGHAI SINGAPORE TAIWAN CONTENTS AWARDS AND RECOGNITIONS 01 MAA Bulletin Issue 51- 52 February 2013 BIM PROJECT CASE STUDY 12 MAA TAIPEI NEW OFFICE 13 PROJECTS 1ST MAY 2011 TO 29TH 14 FEBRUARY 2012 Founded in 1975, MAA is a leading engineering and consulting service provider in the East and Southeast Asian region with a broad range PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES 22 of focus areas including infrastructure, land resources, environment, - PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES buildings, and information technology. - PROFESSIONAL AWARDS/HONORS - SEMINARS AND CONFERENCE - TECHNICAL PUBLICATIONS To meet the global needs of both public and private clients, MAA has developed sustainable engineering solutions - ranging from PERSONNEL PROFILES 26 conceptual planning, general consultancy, engineering design to project management. MAA employs 1000 professional individuals with offices in the Greater China Region (Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Taiwan), Mekong Region (Bangkok), and Southeast Asian Region (Singapore), creating a strong professional network in East/Southeast Asia. MAA’s business philosophy is to provide professional services that will become an asset to our clients with long lasting benefits in this rapidly changing social-economic environment. ASSET represents five key components that underlineMAA ’s principles of professional services: Advanced Technology project Safety client’s Satisfaction ISO 9001 and LAB CERTIFICATIONS Economical Solution Timely -

Roadside Geology of Taiwan: a Field Guide

Roadside geology of taiwan: DȱHOGJXLGH 4UFQIBOJF$IFO About the cover 5IFDPWFSQIPUPEFQJDUTUIFGPMEFE HOFJTTFTJO5BSPLP/BUJPOBM1BSL "MMQIPUPTJOUIJTCPPLCZ 4UFQIBOJF$IFO 'PSNZGBNJMZ PREFACE 5IJTCPPLIBTCFFOXSJUUFOBTQBSUPGUIF 6OJWFSTJUZPG5PSPOUP`T#JH*EFBT&YQMPSJOH (MPCBM5BJXBODPNQFUJUJPO*UIBEBMXBZT CFFONZESFBNUPKVTUDBNQPVUBUBMPDBUJPO GPSBNPOUITBOELOPXFWFSZSPDLBOEPVU DSPQMJLFUIFCBDLPGNZIBOE BOEFWFOUVBMMZ XSJUFBpFMEHVJEFMJLFUIFPOFTUIBUHVJEFE NFUISPVHINZPXOHFPMPHZFEVDBUJPO *EJEO`UHFUUPTUBZGPSNPOUIT*OGBDU *XBTPOMZBCMFUPTUBZGPSPOFNPOUI CVUJU XBTTUJMMBOJODSFEJCMFFYQFSJFODF BOEUSVMZ IVNCMJOH 5BJXBO`THFPMPHZJTWFSZEJWFSTFBOE DPOUBJOTTPNBOZMPDBMTDBMFWBSJBUJPOTXIJDI BUNBOZUJNFTBSFIBSEBOEDIBMMFOHJOHUP pOE*U`TIPUBOEIVNJE NPTRVJUPFTBCPVOE BOEWFOPNPVTTOBLFTMVSLCFOFBUIUIFCSVTI #VUGPSUIPTFXIPBSFXJMMJOHUPUBLFUIFDIBM MFOHFBOEFYQFSJFODFXIBUUIJTMJUUMFJTMBOE DPVOUSZIBTUPP⒎FS ZPVXJMMOPUCFEJTBQ QPJOUFE 4UFQIBOJF C9. Tai Shan Tunnel 42 Table of contents C10. He Huan Shan 45 Southeast Coast 49 SE1. Fanshuliao Bridge 49 SE2. Baxian Cave 50 SE3. East Taiwan Ophiolite 52 Introduction i SE4. Wanrong 55 SE5. Taimali 56 Northern Coast 1 SE6. Lichi Badlands 57 N1. Yu-Ao Roadcut 1 SE7. Sanxiantai 61 N2. Yu-Ao Fishing Port 2 Southwest Coast 67 N3. Yehliu Geopark 4 N4. 13-Level Cu Refinery/Golden Waterfall 9 SW1. Wu Shan Ding 68 N5. Nanya Rock 11 SW2. Xing Yang Nu Hu Bee Farm 70 N6. Heping Dao (Peace Island) 14 SW3. Moon World 71 N7. Elephant’s Trunk/Shen Ao Promontory 16 SW4. Laterites in Southern Taiwan 74 N8. Longdong 20 N9. Bitou Cape 21 N10. Turtle Island 22 N11. Miaoli -

List of Insured Financial Institutions (PDF)

401 INSURED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 2021/5/31 39 Insured Domestic Banks 5 Sanchong City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 62 Hengshan District Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 1 Bank of Taiwan 13 BNP Paribas 6 Banciao City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 63 Sinfong Township Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 2 Land Bank of Taiwan 14 Standard Chartered Bank 7 Danshuei Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 64 Miaoli City Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 3 Taiwan Cooperative Bank 15 Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation 8 Shulin City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 65 Jhunan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 4 First Commercial Bank 16 Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 9 Yingge Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 66 Tongsiao Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 5 Hua Nan Commercial Bank 17 UBS AG 10 Sansia Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 67 Yuanli Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 6 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 18 ING BANK, N. V. 11 Sinjhuang City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 68 Houlong Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 7 Citibank Taiwan 19 Australia and New Zealand Bank 12 Sijhih City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 69 Jhuolan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 8 The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 20 Wells Fargo Bank 13 Tucheng City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 70 Sihu Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 9 Taipei Fubon Commercial Bank 21 MUFG Bank 14 -

Effects of Rehabilitation System with Efficient Vision-Based Action Identification Techniques on Physical Fitness Promotion in Patients with Schizophrenia

Sensors and Materials, Vol. 30, No. 11 (2018) 2653–2664 2653 MYU Tokyo S & M 1706 Effects of Rehabilitation System with Efficient Vision-based Action Identification Techniques on Physical Fitness Promotion in Patients with Schizophrenia Yen-Lin Chen,1 Chin-Hsuan Liu,1 Chao-Wei Yu,1 and Posen Lee2* 1Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Taipei University of Technology, 1, Sec. 3, Zhongxiao E. Rd. Taipei 10608, Taiwan 2Department of Occupational Therapy, I-Shou University, No. 8, Yida Rd., Jiaosu Village, Yanchao District, Kaohsiung 82445, Taiwan (Received March 28, 2018; accepted October 18, 2018) Keywords: rehabilitation system, depth sensors, action identification techniques, schizophrenia, physical fitness Nowadays, there are many human pose estimation systems that extract skeletons or skeleton points from depth sensors. These action identification systems have been developed for somatosensory games for entertainment use, and some of these have been used for medical purposes. Most of these have proven that the action identification technology is practical, but its medical use has not been confirmed. Therefore, besides the general treatment of mental illness, we tried to add a rehabilitation program to promote physical fitness based on a vision- based action sensor system. It is expected to effectively improve the physical functions of patients with mental illness. There are some somatosensory games that claim that they can achieve the effects of sports and entertainment, and some of these have been used for the physical training and physical rehabilitation, but none of them have been used for the physical rehabilitation of patients with schizophrenia. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a rehabilitation system with efficient vision-based action identification techniques on physical fitness promotion in patients with schizophrenia through the sequential-withdrawal design of a single subject research. -

Examining the Implementation of Teaching and Learning Interactions

Nurse Education Today 79 (2019) 74–79 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Nurse Education Today journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/nedt Examining the implementation of teaching and learning interactions of transition cultural competence through a qualitative study of Taiwan T mentors untaking the postgraduate nursing program ⁎ Li-Chun Changa,b, Ching-Wen Chiuc,d, Chih-Ming Hsue,i, Li-Ling Liaof, Hui-Ling Lina,g,h, a School of Nursing, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, No. 261, Wen-Hua 1st Rd., Kwei-Shan, Tao-Yuan 33303, Taiwan, ROC b Department of Nursing, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, No. 261, Wen-Hua 1st Rd., Kwei-Shan, Tao-Yuan 33303, Taiwan, ROC c Department of Health Promotion and Health Education, College of Education, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan, ROC d Department of Nursing, Sijhih Cathay General Hospital, N0.2, Lane 59, Jiancheng Rd., Sijhih Dist., New Taipei City, Taiwan, ROC e Education Department, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, 6.West Sec. Chiapy Road, Putzu City, Chiayi Hsien, Taiwan, ROC f Department of Health Management, I-Shou University, No. 8, Yida Rd., Jiaosu Village Yanchao District, Kaohsiung City 82445, Taiwan, ROC g Chang Gung Medical Education Research Centre, Taiwan, ROC h School of Nursing, Chang Gung University, Taiwan, ROC i Nursing department, Shu Zen College of Medicine and Management, No.452, Huanqiu Rd. Luzhu Dist., Kaohsiung City 82144 Taiwan, ROC ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Cultural competency has been identified as an essential curricular element in undergraduate and Cultural competence graduate nursing programmes. Supporting successful transition to practice is essential for retaining graduate New graduate nurse (NGN) nurses in the workforce and meeting the demand for cultural diversity in health care services. -

Adjunctive Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Healing of Chronic

Wound Care J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017;00(0):1-10. Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Adjunctive Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Healing of Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcers A Randomized Controlled Trial Chen-Yu Chen ¡ Re-Wen Wu ¡ Mei-Chi Hsu ¡ Ching-Jung Hsieh ¡ Man-Chun Chou ABSTRACT PURPOSE: The purpose of this study was to compare the effect of standard wound care with adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) to standard wound care alone on wound healing, markers of infl ammation, glycemic control, amputation rate, survival rate of tissue, and health-related quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). DESIGN: Prospective, randomized, open-label, controlled study. SUBJECTS AND SETTING: The sample comprised 38 patients with nonhealing DFUs who were deemed poor candidates for vascular surgery. Subjects were randomly allocated to an experimental group (standard care plus HBOT, n = 20) or a control group (standard care alone, n = 18). The study setting was a medical center in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan. METHODS: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy was administered in a hyperbaric chamber under 2.5 absolute atmospheric pressure for 120 minutes; subjects were treated 5 days a week for 4 consecutive weeks. Both groups received standard wound care including debridement of necrotic tissue, topical therapy for Wagner grade 2 DFUs, dietary control and pharmacotherapy to maintain optimal blood glucose levels. Wound physiological indices were measured and blood tests (eg, markers of infl ammation) were undertaken. Health-related quality of life was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form. RESULTS: Complete DFU closure was achieved in 5 patients (25%) in the HBOT group (n = 20) versus 1 participant (5.5%) in the routine care group (n = 18) ( P = .001). -

British Journal of Nutrition (2012), 107, 749–754 Doi:10.1017/S0007114511005095 Q the Authors 2011

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (2012), 107, 749–754 doi:10.1017/S0007114511005095 q The Authors 2011 https://www.cambridge.org/core Beneficial effects of catechin-rich green tea and inulin on the body composition of overweight adults Hsin-Yi Yang1,2, Suh-Ching Yang3, Jane C.-J. Chao3 and Jiun-Rong Chen2,3* . IP address: 1Department of Nutrition, I-Shou University, Yanchao District, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, ROC 2Nutrition Research Center, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC 170.106.33.14 3Department of Nutrition and Health Sciences, Taipei Medical University, 250 Wu-Hsin Street, Taipei 110, Taiwan, ROC (Received 8 December 2010 – Revised 16 December 2010 – Accepted 9 February 2011 – First published online 28 October 2011) , on 28 Sep 2021 at 04:29:47 Abstract Green tea catechin has been proposed to have an anti-obesity effect. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the effect of catechin-rich green tea in combination with inulin affects body weight and fat mass in obese and overweight adults. A total of thirty sub- jects were divided into a control group and an experimental group who received 650 ml tea or catechin-rich green tea plus inulin. A reduction of body weight (21·29 (SEM 0·35) kg) and fat mass (0·82 (SEM 0·27) kg) in the experimental group was found after 6 weeks, and no adverse effects were observed. After refraining from consumption for 2 weeks, sustained effects on body weight and fat mass , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at were observed. -

The Differing Privacy Concerns Regarding Exchanging Electronic Medical Records of Internet Users in Taiwan

J Med Syst (2012) 36:3783–3793 DOI 10.1007/s10916-012-9851-1 ORIGINAL PAPER The Differing Privacy Concerns Regarding Exchanging Electronic Medical Records of Internet Users in Taiwan Hsin-Ginn Hwang & Hwai-En Han & Kuang-Ming Kuo & Chung-Feng Liu Received: 31 January 2012 /Accepted: 27 March 2012 /Published online: 20 April 2012 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012 Abstract This study explores whether Internet users have the respondents had substantial privacy concerns regarding different privacy concerns regarding the information EMRs and their educational level and EMR awareness contained in electronic medical records (EMRs) according significantly influenced their privacy concerns regarding to gender, age, occupation, education, and EMR awareness. unauthorized access and secondary use of EMRs. This study Based on the Concern for Information Privacy (CFIP) scale recommends that the Taiwanese government organizes a developed by Smith and colleagues in 1996, we conducted comprehensive EMR awareness campaign, emphasizing un- an online survey using 15 items in four dimensions, namely, authorized access and secondary use of EMRs. Additionally, collection, unauthorized access, secondary use, and errors, to cultivate the public’s understanding of EMRs, the gov- to investigate Internet users’ concerns regarding the privacy ernment should employ various media, especially Internet of EMRs under health information exchanges (HIE). We channels, to promote EMR awareness, thereby enabling the retrieved 213 valid questionnaires. The results indicate that public to accept the concept and use of EMRs. People who are highly educated and have superior EMR awareness should be given a comprehensive explanation of how hos- H.-G. Hwang ’ Institute of Information Management, pitals protect patients EMRs from unauthorized access and National Chiao-Tung University, secondary use to address their concerns. -

Experimental Animals Exp

Experimental Animals Exp. Anim. 70(3), 333–343, 2021 Original Generation of avian-derived anti-B7-H4 antibodies exerts a blockade effect on the immunosuppressive response Tsai-Yu LIN1)*, Tsung-Hsun TSAI2)*, Chih-Tien CHEN3,4), Tz-Wen YANG1), Fu-Ling CHANG5), Yan-Ni LO1), Ting-Sheng CHUNG2), Ming-Hui CHENG6), Wang-Chuan CHEN7,8), Keng-Chang TSAI10,11) and Yu-Ching LEE1,9,11–13) 1)TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, No. 250, Wuxing Street, Taipei 11031, Taiwan 2)Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, No.2, Zhongzheng 1st Rd., Lingya Dist., Kaohsiung 80284, Taiwan 3)Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, No.110, Sec.1, Jianguo N. Rd., Taichung 40201, Taiwan 4)Department of Surgery, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, No.1650, Taiwan Boulevard Sect. 4, Taichung 40705, Taiwan 5)Ph.D. Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University and Academia Sinica, No. 250, Wuxing Street, Taipei 11031, Taiwan 6)Department of Laboratory Medicine, Lo-Hsu Medical Foundation, Lotung Poh-Ai Hospital, No. 83, Nanchang St., Luodong Township, Yilan 26546, Taiwan 7)The School of Chinese Medicine for Post Baccalaureate, I-Shou University, No.1, Sec. 1, Syuecheng Rd., Dashu District, Kaohsiung 84001, Taiwan 8)Department of Chinese Medicine, E-Da Hospital, No.8, Yida Rd., Jiaosu Village Yanchao District, Kaohsiung 82445, Taiwan 9)Ph.D. Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, No. 250, Wuxing Street, Taipei 11031, Taiwan 10)National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine, Ministry of Health and Welfare, No. -

Comparison of Overall Survival on Surgical Resection Versus Transarterial Chemoembolization with Or Without Radiofrequency Ablat

Lin et al. BMC Gastroenterology (2020) 20:99 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01235-w RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Comparison of overall survival on surgical resection versus transarterial chemoembolization with or without radiofrequency ablation in intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis Chih-Wen Lin1,2,3,4,5,6,7†, Yaw-Sen Chen4,8†, Gin-Ho Lo1,2,4, Yao-Chun Hsu2,4, Chia-Chang Hsu3,4, Tsung-Chin Wu1,4, Jen-Hao Yeh1,2,4, Pojen Hsiao1,4, Pei-Min Hsieh8,9, Hung-Yu Lin4,5,8,9, Chih-Wen Shu4 and Chao-Ming Hung4,8,9* Abstract Background: Patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are recommended to undergo transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE). However, TACE in combination with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is not inferior to surgical resection (SR), and the benefits of surgical resection (SR) for BCLC stage B HCC remain unclear. Hence, this study aims to compare the impact of SR, TACE+RFA, and TACE on analyzing overall survival (OS) in BCLC stage B HCC. Methods: Overall, 428 HCC patients were included in BCLC stage B, and their clinical data and OS were recorded. OS was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression analysis. Results: One hundred forty (32.7%) patients received SR, 57 (13.3%) received TACE+RFA, and 231 (53.9%) received TACE. The OS was significantly higher in the SR group than that in the TACE+RFA group [hazard ratio (HR): 1.78; 95% confidence incidence (CI): 1.15–2.75, p = 0.009]. -

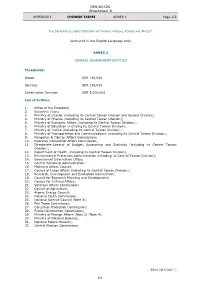

GPA/W/326 Attachment K K1

GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 1/2 THE SEPARATE CUSTOMS TERRITORY OF TAIWAN, PENGHU, KINMEN AND MATSU* (Authentic in the English Language only) ANNEX 1 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES Thresholds: Goods SDR 130,000 Services SDR 130,000 Construction Services SDR 5,000,000 List of Entities: 1. Office of the President; 2. Executive Yuan; 3. Ministry of Interior (including its Central Taiwan Division and Second Division); 4. Ministry of Finance (including its Central Taiwan Division); 5. Ministry of Economic Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 6. Ministry of Education (including its Central Taiwan Division); 7. Ministry of Justice (including its Central Taiwan Division); 8. Ministry of Transportation and Communications (including its Central Taiwan Division); 9. Mongolian & Tibetan Affairs Commission; 10. Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission; 11. Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (including its Central Taiwan Division); 12. Department of Health (including its Central Taiwan Division); 13. Environmental Protection Administration (including its Central Taiwan Division); 14. Government Information Office; 15. Central Personnel Administration; 16. Mainland Affairs Council; 17. Council of Labor Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 18. Research, Development and Evaluation Commission; 19. Council for Economic Planning and Development; 20. Council for Cultural Affairs; 21. Veterans Affairs Commission; 22. Council of Agriculture; 23. Atomic Energy Council; 24. National Youth Commission; 25. National Science Council (Note 3); 26. Fair Trade Commission; 27. Consumer Protection Commission; 28. Public Construction Commission; 29. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Note 2) (Note 4); 30. Ministry of National Defense; 31. National Palace Museum; 32. Central Election Commission. … 2014 (WT/Let/…) K1 GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 2/2 * In English only.