Conference Report 13Th Annual Conference of Public Works and Environment Committees of Australian Parliaments 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I Have Fond Memories of the Friendly, Knowledgeable Giraffe

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I have fond memories of the friendly, knowledgeable giraffe. Harold takes you on a magical journey exploring and learning about healthy eating, our body - how it works and ways we can be active in order to stay happy and healthy. It gives me such joy to see how excited my daughter is to visit Harold and know that it will be an experience that will stay with her too. Melanie, parent, Turramurra Public School What’s inside Who we are 03 Our year Life Education is the nation’s largest not-for-profit provider of childhood preventative drug and health education. For 06 Our programs almost 40 years, we have taken our mobile learning centres and famous mascot – ‘Healthy Harold’, the giraffe – to 13 Our community schools, teaching students about healthy choices in the areas of drugs and alcohol, cybersafety, nutrition, lifestyle 25 Our people and respectful relationships. 32 Our financials OUR MISSION Empowering our children and young people to make safer and healthier choices through education. OUR VISION Generations of healthy young Australians living to their full potential. LIFE EDUCATION NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report Our year: Thank you for being part of Life Education NSW Together we worked to empower more children in NSW As a charity, we’re grateful for the generous support of the NSW Ministry of Health, and the additional funds provided by our corporate and community partners and donors. We thank you for helping us to empower more children in NSW this year to make good life choices. -

Legislative Assembly

22337 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday 11 May 2010 __________ The Speaker (The Hon. George Richard Torbay) took the chair at 1.00 p.m. The Speaker read the Prayer and acknowledgement of country. BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Notices of Motions General Business Notices of Motions (General Notices) given. [During the giving of notices of motions.] Mr Daryl Maguire: Point of order: Mr Speaker, you have ruled previously on the length of notices of motions. As important as this notice of motion is, I draw your attention to its length and ask that you remind members to comply with your previous ruling. The SPEAKER: Order! I ask the Clerks to amend the notice of motion to ensure that it conforms to the standing orders. Mr Paul Gibson: Point of order: I draw attention to the length of the notices of motions and ask that they be reviewed. The SPEAKER: Order! I uphold the point of order. I have ruled previously in relation to the length of notices of motions. Members should avail themselves of the advice of the Clerks in relation to their notices of motions. Lengthy notices of motions will be amended by the Clerks at my request. PRIVATE MEMBERS' STATEMENTS __________ ANZAC FIELD OF REMEMBRANCE, THE ENTRANCE Mr GRANT McBRIDE (The Entrance) [1.10 p.m.]: The Entrance and Long Jetty War Widows Guild again invited me to attend the dedication service for the Anzac Field of Remembrance at The Entrance Memorial Park Cenotaph. As members are aware, Anzac Day marks the anniversary of the first major military action fought by Australian and New Zealand forces during the First World War; the soldiers were known as Anzacs. -

Committee on Transport and Infrastructure

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Committee on Transport and Infrastructure REPORT 1/55 – NOVEMBER 2012 UTILISATION OF RAIL CORRIDORS New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committee on Transport and Infrastructure. Utilisation of rail corridors / Legislative Assembly, Committee on Transport and Infrastructure [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2012. [114] p. ; 30 cm. (Report no. 1/55 Committee on Transport and Infrastructure) “November 2012”. Chair: Charles Casuscelli, RFD MP. ISBN 9781921686573 1. Railroads—New South Wales—Planning. 2. Railroads—Joint use of facilities—New South Wales. I. Casuscelli, Charles. II. Title. III. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committee on Transport and Infrastructure. Report ; no. 1/55 (385.312 DDC22) The motto of the coat of arms for the state of New South Wales is “Orta recens quam pura nites”. It is written in Latin and means “newly risen, how brightly you shine”. UTILISATION OF RAIL CORRIDORS Contents Membership ____________________________________________________________ iii Terms of Reference ________________________________________________________iv Chair’s Foreword __________________________________________________________ v Executive Summary ________________________________________________________vi List of Findings and Recommendations ________________________________________ ix CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

(Liberal) Barbara Perry, MP, Member for Auburn

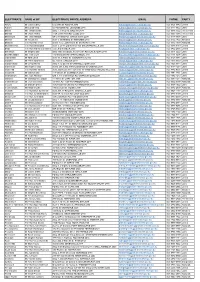

Mr Greg Aplin, MP, Member for Albury (Liberal) 612 Dean Street Albury NSW 2640 Ph: 02 6021 3042 Email: [email protected] Barbara Perry, MP, Member for Auburn (Labor) 54-58 Amy Street Regents Park NSW 2143 Ph: 02 9644 6972 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @BarbaraPerry_MP Donald Page, MP, Member for Ballina (National) 7 Moon Street Ballina NSW 2478 Ph: 02 6686 7522 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @DonPageMP Jamie Parker, MP, Member for Balmain (Greens) 112A Glebe Point Road Glebe NSW 2037 Ph: 02 9660 7586 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @GreensJamieP Tania Mihailuk, MP, Member for Bankstown (Labor) 402-410 Chapel Road Bankstown NSW 2200 Ph: 02 9708 3838 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @TaniaMihailukMP Kevin Humphries, MP, Member for Barwon (National) 161 Balo Street Moree NSW 2400 Ph: 02 6752 5002 Email: [email protected] Paul Toole, MP, Member for Bathurst (National) 229 Howick Street Bathurst NSW 2795 Ph: 02 6332 1300 Email: [email protected] David Elliott, MP, Member for Baulkham Hills (Liberal) Suite 1 25-33 Old Northern Road Baulkham Hills NSW 2153 Ph: 02 9686 3110 Email: [email protected] Andrew Constance, MP, Member for Bega (Liberal) 122 Carp Street Bega NSW 2550 Ph: 02 6492 2056 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @AndrewConstance John Robertson, MP, Member for Blacktown (Labor) Shop 3063 Westfield Shopping Centre Flushcombe Road Blacktown NSW 2148 Ph: 02 9671 5222 Email: [email protected] Twitter: -

NSW Govt Lower House Contact List with Hyperlinks Sep 2019

ELECTORATE NAME of MP ELECTORATE OFFICE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PARTY Albury Mr Justin Clancy 612 Dean St ALBURY 2640 [email protected] (02) 6021 3042 Liberal Auburn Ms Lynda Voltz 92 Parramatta Rd LIDCOMBE 2141 [email protected] (02) 9737 8822 Labor Ballina Ms Tamara Smith Shop 1, 7 Moon St BALLINA 2478 [email protected] (02) 6686 7522 The Greens Balmain Mr Jamie Parker 112A Glebe Point Rd GLEBE 2037 [email protected] (02) 9660 7586 The Greens Bankstown Ms Tania Mihailuk 9A Greenfield Pde BANKSTOWN 2200 [email protected] (02) 9708 3838 Labor Barwon Mr Roy Butler Suite 1, 60 Maitland St NARRABRI 2390 [email protected] (02) 6792 1422 Shooters Bathurst The Hon Paul Toole Suites 1 & 2, 229 Howick St BATHURST 2795 [email protected] (02) 6332 1300 Nationals Baulkham Hills The Hon David Elliott Suite 1, 25-33 Old Northern Rd BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 [email protected] (02) 9686 3110 Liberal Bega The Hon Andrew Constance 122 Carp St BEGA 2550 [email protected] (02) 6492 2056 Liberal Blacktown Mr Stephen Bali Shop 3063 Westpoint, Flushcombe Rd BLACKTOWN 2148 [email protected] (02) 9671 5222 Labor Blue Mountains Ms Trish Doyle 132 Macquarie Rd SPRINGWOOD 2777 [email protected] (02) 4751 3298 Labor Cabramatta Mr Nick Lalich Suite 10, 5 Arthur St CABRAMATTA 2166 [email protected] (02) 9724 3381 Labor Camden Mr Peter Sidgreaves 66 John St CAMDEN 2570 [email protected] (02) 4655 3333 Liberal -

Victoria New South Wales

Victoria Legislative Assembly – January Birthdays: - Ann Barker - Oakleigh - Colin Brooks – Bundoora - Judith Graley – Narre Warren South - Hon. Rob Hulls – Niddrie - Sharon Knight – Ballarat West - Tim McCurdy – Murray Vale - Elizabeth Miller – Bentleigh - Tim Pallas – Tarneit - Hon Bronwyn Pike – Melbourne - Robin Scott – Preston - Hon. Peter Walsh – Swan Hill Legislative Council - January Birthdays: - Candy Broad – Sunbury - Jenny Mikakos – Reservoir - Brian Lennox - Doncaster - Hon. Martin Pakula – Yarraville - Gayle Tierney – Geelong New South Wales Legislative Assembly: January Birthdays: - Hon. Carmel Tebbutt – Marrickville - Bruce Notley Smith – Coogee - Christopher Gulaptis – Terrigal - Hon. Andrew Stoner - Oxley Legislative Council: January Birthdays: - Hon. George Ajaka – Parliamentary Secretary - Charlie Lynn – Parliamentary Secretary - Hon. Gregory Pearce – Minister for Finance and Services and Minister for Illawarra South Australia Legislative Assembly January Birthdays: - Duncan McFetridge – Morphett - Hon. Mike Rann – Ramsay - Mary Thompson – Reynell - Hon. Carmel Zollo South Australian Legislative Council: No South Australian members have listed their birthdays on their website Federal January Birthdays: - Chris Bowen - McMahon, NSW - Hon. Bruce Bilson – Dunkley, VIC - Anna Burke – Chisholm, VIC - Joel Fitzgibbon – Hunter, NSW - Paul Fletcher – Bradfield , NSW - Natasha Griggs – Solomon, ACT - Graham Perrett - Moreton, QLD - Bernie Ripoll - Oxley, QLD - Daniel Tehan - Wannon, VIC - Maria Vamvakinou - Calwell, VIC - Sen. -

Premier & Cabinet

~,,1. Premier NSW-- GOVERNMENT & Cabinet Ref: A3703926 Mr David Blunt Clerk of the Parliaments Legislative Council Parliament House Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Mr Blunt Order for Papers - Funding for Independent Disability Advocacy Services I refer to the above resolution of the Legislative Council under Standing Order 52 made on 17 June 2020 and your correspondence of that date. I am now delivering to you documents referred to in that resolution. The documents have been obtained from: • Office of the Minister for Families, Communities and Disability Services • Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ), and • NSW Treasury. Enclosed at Annexure 1 are certification letters from the following officers certifying that, to the best of their knowledge, either all documents held and covered by the terms of the resolution and lawfully required to be provided have been provided or that no documents are held: • Chief of Staff, Office of the Treasurer • Chief of Staff, Office of the Minister for Families, Communities and Disability Services • Secretary, NSW Treasury • Secretary, DCJ. The letter from the Secretary of DCJ advises that DCJ are providing the first tranche of documents that are caught by the resolution. The letter also advises that it will provide the second and final tranche to the Department of Premier and Cabinet by Friday, 10 July 2020. DCJ will also provide the required certification at that time. Enclosed at Annexure 2 is an index of all the non-privileged documents that have been provided in response to the resolution. In accordance with Item 5(a) of Standing Order 52, those documents for which a claim for privilege has been made have been separately indexed and the case for privilege has been noted. -

Standing Orders and Procedure Committee

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Standing Orders and Procedure Committee REPORT 3/56 – MARCH 2016 CHANGES TO THE ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AND CONSEQUENTIAL CHANGES TO THE SESSIONAL ORDERS LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY STANDING ORDERS AND PROCEDURE COMMITTEE CHANGES TO THE ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AND CONSEQUENTIAL CHANGES TO THE SESSIONAL ORDERS REPORT 3/56 – MARCH 2016 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. Changes to the Routine of Business and consequential changes to the Sessional Orders / Legislative Assembly, Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2015. – [15] pages ; 30 cm. (Report ; no. 3/56) Chair: The Hon. Shelley Hancock MP. “March 2016”. ISBN [TBC] 1. New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly—Rules and practice. 2. Parliamentary practice—New South Wales. I. Title. II. Hancock, Shelley. III. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. Report ; no. 3/56. 328.944 (DDC22) The motto of the coat of arms for the state of New South Wales is “Orta recens quam pura nites”. It is written in Latin and means “newly risen, how brightly you shine”. CHANGES TO THE ROUTINE OF BUSINESS Contents Membership _____________________________________________________________ ii Terms of reference _______________________________________________________ iii Speaker’s foreword ________________________________________________________iv List of recommendations -

Blue Lawyer Photo Employee Newsletter

O C T O B E R 2 0 1 9 The Civil Source Newsletter of the New South Wales Council for Civil Liberties Historic Abortion Reform Bill passed by NSW Parliament B Y N S W C C L V I C E P R E S I D E N T , D R L E S L E Y L Y N C H This issue: Decriminalisation of Abortion in NSW On Thursday 26th September the NSW Parliament at long last acted to 2019 Annual Dinner remove abortion from the criminal law and regulate it as a women’s health Inaugural Awards for issue with the passage of the Reproductive Health Care Reform Bill 2019 - Excellence in Civil Liberties Journalism (now called the Abortion Reform Law 2019). This is a big and very overdue Action on Climate historical moment for women. NSWCCL Annual General Meeting Women in NSW can now legally access terminations up to 22 weeks into In the media their pregnancy in consultation with their doctor. After 22 weeks they can access a termination in consultation with two medical practitioners. Achieving this in NSW has required a very, very long campaign by numerous organisations and individuals with ups and many downs since the 1960s. This most recent and successful campaign push over several years was sustained by a broad and powerful alliance of organisations encompassing women’s, legal, health, civil liberties and human rights issues. Some of these - such as WEL and NSWCCL - were long term players for abortion reform of 50 years plus. Cont'd - Historic Abortion Reform Bill for NSW This campaign knew it had strong, majority support in the community. -

Conference Attendance Report

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY el Standing Committee on Natural Resource Management (Climate Change) Report on Conference Attendance 14th Annual Conference of Parliamentary Public Works and Environment Committees Report No. 6/54 – April 2010 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Committee on Natural Resource Management (Climate Change) Report on conference attendance : 14th Annual Conference of Parliamentary Public Works and Environment Committees / NSW Parliament, Legislative Assembly, Standing Committee on Natural Resource Management (Climate Change). [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2010. – [18] p. ; 30 cm. (Report / Standing Committee on Natural Resource Management (Climate Change) ; no. 6/54) Chair: Matt Brown, MP April 2010 ISBN: 978-1-921686-11-5 1. Annual Conference of Public Works and Environment Committees of Australian Parliaments (14th : 2009 : Hobart, Tas.) 2. Conservation of natural resources—Australia—Congresses. 3. Environmental policy— Australia—Congresses. I. Title. II. Brown, Matt. III. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Committee on Natural Resources Management (Climate Change). Report ; no. 6/54 333.72 (DDC 22) Report on Conference Attendance TABLE OF CONTENTS Membership and staff .............................................................................................ii Committee terms of reference ............................................................................... iii Chair’s foreword.....................................................................................................iv -

13 MAY 2021 CHAMBER Social Distancing

FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT, FIRST SESSION May 2021 NO. 3/2021: 4 – 13 MAY 2021 M T W T F 3 4 5 6 7 10 11 12 13 14 This document provides a summary of significant procedural events and precedents in the Legislative Assembly. It is produced at the end of each sitting period. Where applicable the relevant Standing Orders are noted. CHAMBER Social distancing On Tuesday 4 May, following a motion from the Leader of the House, the Hon. Mark Speakman MP, the House agreed to an altered seating plan which allowed all 93 Members to sit in the Chamber and galleries during Question Time. The change in seating arrangements followed an inspection of the Chamber by NSW Health. In a Statement made before Question Time, the Speaker advised that there was designated seating for each Member and, to minimise risk, Members were not to move unnecessarily about the Chamber and were to moderate their voices. Additionally, measures had been introduced to increase airflow into the Chamber. However, the expanded seating arrangements were short lived, and on Thursday 6 May, following a number of cases of locally acquired COVID-19 infections, the House agreed to a motion of the Leader of the House providing for Chamber seating to revert to the previous arrangement of 52 Members seated on the floor and in the galleries. Votes and Proceedings: 4/5/2021, p. 1137 and p. 1138; 6/5/2021, p. 1162. Hansard (Proof): 4/5/2021, p. 10. SPEAKER Deputy Speaker opening the sitting Due to the absence of the Speaker, on Thursday 13 May the Deputy Speaker, the Hon. -

Business Paper

31 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2011 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT ___________________ BUSINESS PAPER No. 5 TUESDAY 10 MAY 2011 ___________________ GOVERNMENT BUSINESS ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Duties Amendment (Senior's Principal Place of Residence Duty Exemption) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate, on the motion of Mr Mike Baird, “That this bill be now agreed to in principle” (introduced 9 May 2011—Mr Richard Amery). ADDRESS-IN-REPLY ORDER OF THE DAY— 1 The Governor’s Opening Speech: resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Ms Robyn Parker, that the following Address in Reply to the Governor’s Opening Speech be now adopted by this House— “To Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir, Companion of the Order of Australia, Commander of the Royal Victorian Order and Governor of the State of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY – We, the Members of the Legislative Assembly of the State of New South Wales, in Parliament assembled, desire to express our thanks for Your Excellency’s speech, and to express our loyalty to Australia and the people of New South Wales. 32 BUSINESS PAPER Tuesday 10 May 2011 We assure Your Excellency that our earnest consideration will be given to the measures to be submitted to us, and that we will faithfully carry out the important duties entrusted to us by the people of New South Wales. We join Your Excellency in the hope that our labours may be so directed as to advance the best interests of all sections of the community.” (Ms Gladys Berejiklian) BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE – PETITIONS ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Petition— from certain citizens requesting a major review of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, the repeal of Part 3A of the Act and the appointment of a Special Commission of Inquiry into the Barangaroo site development processes.