WA Pro Bono Report Final Sept 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Clerkship at Henry Davis York Provided Me with and Professional Goals

Acknowledgments Many thanks to all those who made possible the production and publication of this year’s Careers Guide. SULS EXECUTIVE Corrs Chambers Westgarth Herbert Smith Freehills Alistair Stephenson (Vice President, Careers) Gilbert + Tobin James Higgins (Vice President, Social Justice) Henry Davis York Ben Paull (Sponsorship Director) King & Wood Mallesons Nicholas Simone (Publications Director) Johnson Winter & Slattery Judy Zhu (Design Officer) GOLD SPONSORS CAREERS GUIDE TEAM Allens Michael de Waal (Editor-in-Chief) Baker & McKenzie Alice Au Gadens Lawyers Jane Chandler Minter Ellison Emily Dale Catherine Gu CORPORATE SPONSORS Isabella Partridge Olivia Ronan A.T. Kearney Connie Ye Australian National University College of Law PHOTOGRAPHY JADE Barnet Jones Day Judy Zhu K&L Gates Lander & Rogers PRINTING Palgrave Macmillan Thomsons Lawyers Kopystop Pty Ltd Webb Henderson PLATINUM SPONSORS We would finally like to thank Sydney Law School and the University of Sydney Union for their continuing support of SULS Allen & Overy and its publications. Ashurst Clayton Utz ISSN 1839-1044 Michael de Waal Alice Au Jane Chandler Emily Dale Catherine Gu Isabella Partridge Olivia Ronan Connie Ye Contents Contents ........................... 1 NON-SPONSORS Addisons ..................................... 90 Foreword ........................... 3 Arnold Bloch Leibler ........................... 91 Brown Wright Stein ............................ 92 Human Resources ................... 4 Clifford Chance ............................... 93 Davis Polk & -

Navigating Employment and Labour Relations in Australia a GUIDE for EMPLOYERS

Navigating Employment and Labour Relations in Australia A GUIDE FOR EMPLOYERS 2018 This publication is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to. Readers should take legal advice before applying the information contained in this publication to specific issues or transactions. For more information please contact us at [email protected]. Ashurst Australia (ABN 75 304 286 095) is a general partnership constituted under the laws of the Australian Capital Territory and is part of the Ashurst Group. Further details about Ashurst can be found at www.ashurst.com. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from Ashurst. Enquiries may be emailed to [email protected]. © Ashurst 2018 The centrepiece of the Australian industrial relations legislative framework is the Fair Work Act 2009. The national system created by the Fair Work Act is likely to govern Australian employment and labour relations in a relatively settled way for some years to come. The Australian Productivity Commission released their report on 21 December 2015 following an inquiry into the features of the Australian workplace relations framework. Contents Individual employment relationships 2 Collective employment relationships 2 National Employment Standards 3 Awards – ancient & modern 3 Enterprise agreements 4 Representative role of trade unions 5 Union right of entry 5 Staff relationships 6 Transfer of business 6 Protected industrial action 7 Dealing with unlawful industrial action 8 Fair Work Act and industrial action flow-chart 9 Limits on certain senior management employment termination benefits 10 Dealing with dismissals 11 Other Protections 12 NAVIGATING EMPLOYMENT AND LABOUR RELATIONS IN AUSTRALIA – A GUIDE FOR EMPLOYERS Page 1 INDIVIDUAL EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIPS Employment is contractual at its base. -

Anti Bribery Laws in Australia PDF 2.1 MB

Anti-Bribery Laws in Australia QUICK GUIDE 2019 This guide provides an overview of the Australian law relating to bribery and corruption, including bribery of foreign officials, and some practical tips to manage associated risks. Topics covered include: • Bribery of foreign public officials • Liability of corporations for their representatives • False accounting offences • Domestic bribery • Political donations • Enforcement of contracts procured by bribery • Practical steps to manage risks • Practical steps if you encounter a problem This publication is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to. Readers should take legal advice before applying the information contained in this publication to specific issues or transactions. For more information please contact us at [email protected]. Ashurst Australia (ABN 75 304 286 095) is a general partnership constituted under the laws of the Australian Capital Territory and is part of the Ashurst Group. Further details about Ashurst can be found at www.ashurst.com . No part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from Ashurst. Enquiries may be emailed to [email protected]. © Ashurst 2019 2 ANTI-BRIBERY LAWS IN AUSTRALIA | 2019 Introduction In a world where business is conducted across national boundaries, foreign bribery and corruption is increasingly in the spotlight. More countries, including Australia, are becoming increasingly active in investigating suspected bribery both within and outside their borders and bringing enforcement action. Organisations need to be conscious of anti-bribery legislation, have policies and procedures in place to comply with that legislation and take steps to ensure that compliance is embedded within the organisation’s culture. -

Ship Guide 2012

ANU LSS Clerkship Guide 2012 ship Guide A career at King & Wood Mallesons offers you both global and local opportunities, the most interesting work, the best training and all the support you need to become a great lawyer. So, if you’re smart, social and up for a challenge – get ready to... SHAPE YOUR WORLD 2 Contents Introduction 4 How to Write a Great Cover Letter 5 Drafting Your CV 7 Interview Dos and Don'ts 8 Firms and Sponsors -King & Wood Mallesons 10 -Clayton Utz 12 -Ashurst 14 -Freehills 16 -Gadens 19 -Baker & McKenzie 20 -Allens 22 -Norton Rose 24 -Gilbert + Tobin 26 -Webb Henderson 29 -Corrs Chambers Westgarth 30 -Allen & Overy 32 -ANU Legal Workshop GDLP 34 Clerkship Dates 35 Firm Directory 36 3 Introduction Dear sponsors and students, Welcome to the 2012 King & Wood Mallesons Clerkship Guide! With mid-year almost upon us, it is once again time to prepare for summer clerkships! Clerkships are an excellent way for students to gain practical experience and acquire a taste of firm culture in preparation for graduate positions. They are also a valuable means of scouting talent for firms. It is with these aims in mind that the King & Wood Mallesons Clerkship Guide has been compiled for you, as an overview of the many, exciting clerkship initiatives offered by our great Australian and global firms. In the following pages, you will find profiles and messages from our sponsors, a list of proposed dates for clerkship applications, and advice on applying for clerkships from past clerks. Some of our former clerks from ANU also dispense their insights about writing letters of application, and disclose their techniques for approaching the coveted interview. -

Working Collaboratively: COMMUNITY LEGAL CENTRES and PRO BONO PARTNERSHIPS

Working collaboratively: COMMUNITY LEGAL CENTRES AND PRO BONO PARTNERSHIPS Community Legal Centres (CLCs) are independent, not-for-profit, national children’s and youth law community-based organisations centre – lawmail that provide free legal and related The National Children’s and services to the public, focusing on Youth Law Centre (NCYLC) is disadvantaged people and those with a Community Legal Centre special needs. They offer creative, dedicated to working for and effective and targeted solutions to in support of Australia’s their clients’ legal problems and, children and young wherever possible, to the causes of people, their rights those legal problems. and access to justice. CLCs’ Pro Bono Partners and Established in 1993, their contributions the NCYLC uniquely provides all of its legal CLCs, both generalist Centres serving education and advice their local geographic community and online – through its the specialist, often state-wide, services legal information that focus on a particular target group, website, Lawstuff, and such as women experiencing or at its email legal advice risk of violence, tenants, or welfare service, Lawmail. The use of recipients; are adept at garnering pro technology makes legal services particularly accessible to young people, bono support from lawyers from private who prefer using mobile/online forms of communication, and those law firms. The ability of CLCs to leverage living in rural, regional and remote areas. such high levels of support through pro bono partnerships is a distinguishing Lawmail is a free legal service for Australians under 18 and their feature of the sector. You’ll read some of advocates. Added to the Lawstuff website in October 1998, the Lawmail their diverse stories in this brochure. -

Last Name Designation First Name Middle Name Ab Firm Admitted

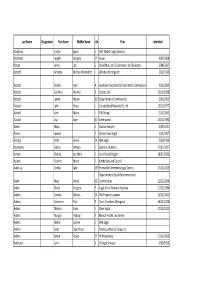

Last Name Designation First Name Middle Name Ab Firm Admitted Abadines Evelyn Jayne E ANZ Wealth Legal Services Abberton Joseph Gregory EP Lavan 3/07/2008 Abbey Jenny Lee E David Moss and Co Barristers and Solicitors 3/04/2017 Abbott Anthony Michael Rutherford I Woodside Energy Ltd 2/02/1990 Abbott Danille Kym A Australian Securities & Investments Commission 3/11/2009 Abbott Geoffrey Michael B Abbott, GM 23/12/1988 Abbott Janine Maree SG Department of Communities 2/03/2005 Abbott John Bruce I Consolidated Minerals Pty Ltd 23/12/1977 Abbott Kym Marie I Toll Group 2/11/2005 Abbott Lisa Jane SG Lotterywest 21/12/1990 Abela Maya E Lawton Lawyers 2/09/2011 Aberin Joanne E United Voice Legal 2/11/2007 Ablong Brett Reece DI HBA Legal 2/06/1999 Abrahams Zubayr Adnaan E Solomon Brothers 17/07/2017 Acham Shelley Joy Mary E Lane Buck & Higgins 18/07/2006 Acland Gemma Marni E Kimberley Land Council Adair‐La Danika Jade NP Fremantle Community Legal Centre 17/12/2013 Department of Local Government and Adam Mary Verna SG Communities 22/12/2004 Adam Shane Gregory E Legal Aid of Western Australia 21/12/1984 Adams Corinne Belinda DI WA Property Lawyers 22/12/2005 Adams Katherine Pilar E Corrs Chambers Westgarth 16/12/2016 Adams Melissa Karin E Pacer Legal 17/12/2013 Adams Morgan Padraig E Mental Health Law Centre Adams Naomi Leanne E HBA Legal Adams Scott Dale Victor I Fortescue Metals Group Ltd Adams Simon Royce EP HFW Australia 21/12/2000 Adamson Lynn S LA Legal Services 2/09/1993 Addison James David E Travers Smith LLP 18/12/2012 Adesina Olufunmilayo -

Petroleum in Australia an Introduction for Investors

Petroleum in Australia An introduction for investors 2015 Foreword We are pleased to publish Petroleum in Australia – An introduction for investors. The Australian petroleum sector is important to Australia’s economy and offers significant opportunities for investors. Strong and substantial growth in the Asia Pacific economies has created significant trade and investment flows between the region and the resources rich Australian continent. The high level of interest shown in the petroleum sector from China, India and Japan, in particular, has been an impetus for us developing this guide. We have a strong commitment to the Asia Pacific region and our regional clients. Ashurst has offices in Singapore, Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai and Tokyo and an associated office in Jakarta. The purpose of this guide is to assist you, as a prospective investor, to gain a better understanding of: • Australia’s legal and regulatory petroleum framework; and • practical aspects of Australia’s petroleum industry. Ashurst’s Energy and Resources practice is recognised as one of the best in the region. Our expertise in the sector is supported by experience in related areas such as infrastructure, engineering and construction, native title, project finance, industrial relations, corporate, mergers and acquisitions, litigation and dispute resolution, taxation and property. Our considerable experience in assisting our regional clients on their Australian petroleum investments, combined with our strong commitment to client service, means we are the legal advisor who can assist you and your team to achieve your goals. We wish you every success for your business ventures in Australia. Peter Vaughan Global Co-head – Oil and Gas, Ashurst This publication is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to. -

Ashurst Securitisation Expertise – Australia PDF 2.18 MB

Securitisation Expertise Australia 2018 A premier securitisation team A TIER ONE SECURITISATION TEAM AT THE CUTTING EDGE OF WITH GLOBAL REACH SECURITISATION Ashurst is a tier one market leader in the field of Our innovative team has extensive experience in all securitisation. Our team in Australia is one of the largest in securitisation structures and asset classes. The team has the market and is connected to a network of specialists in recently worked on many innovative warehouse transactions our offices in New York, London and continental Europe and and quasi-securitisation transactions in the domestic Asia (including Hong Kong, Singapore and China). Backed by and offshore markets involving a range of asset classes an international network spanning 25 offices and including and structures, including ABS, trade receivables, FinTech a leading global regulatory team, Ashurst has the expertise securitisations, green securitisations, quasi-government and depth of resources to advise on the most challenging of funding, CMBS, Islamic structures and bespoke derivatives. securitisations in the global markets. Our securitisation partners also have significant experience advising in relation to complex securitisation restructurings. ACTING ON THE MARKET’S MOST SIGNIFICANT TRANSACTIONS Ashurst has had leading roles in the key market transactions of recent times including on the GE portfolio sales (Projects Clarendon (credit cards and personal loans), Paringa (ABL, Tier 1 in Capital Markets aviation and equipment) and Kensington (commercial Structured Finance & Securitisation property)), as well as the ANZ Bank owned Esanda sale. We advise the full spectrum of securitisation participants, IFLR1000 2011 – 2018 including issuers, arrangers, dealers, funders, originators, professional trustees and special purpose vehicle managers. -

Asia Pacific Competition Law Handbook 2014-15

Asia-Pacific Competition Law Handbook 2014/15 R elated publications OUR GLOBAL COMPETITION AND REGULATION TEAM (2014) This brochure is a snapshot of our global Competition legal team at Ashurst. It highlights their star expertise, in-depth knowledge and provides an overview of our full range of competition law areas, in which our team can provide strategic and commercially focused advice to clients around the globe. OUR competition and REGULATION TEAM – AUstRALIA AND ASIA PACIFIC (2014) This brochure is an overview of the Australian and Asia Pacific Competition legal team at Ashurst. It highlights their star expertise, in-depth knowledge and provides an overview of legal areas in which our team can provide strategic and commercially focused advice to clients, within the region and around the globe. AUstRALIA – AN intRODUction FOR inVestoRS (2013) This guide assists foreign investors to understand the legal, taxation and regulatory requirements of investing in the Australian market. This guide was published jointly with Austrade, the Australian Government’s trade and investment development agency. This publication is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to. Readers should take legal advice before applying the information contained in this publication to specific issues or transactions. For more information please contact us at Ashurst LLP, 12 Marina Boulevard, #24-01 Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3, Singapore 018892, +65 6221 2214, www.ashurst.com Ashurst is not licensed to practise local law in all of the jurisdictions referred to. Ashurst can work with local counsel in jurisdictions where it does not have local practice capability to arrange the necessary advice for clients with specific issues. -

Sharma by Her Litigation Representative Sister Marie Brigid Arthur V Minister for the Environment [2021] FCA 560

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA Sharma by her litigation representative Sister Marie Brigid Arthur v Minister for the Environment [2021] FCA 560 File number: VID 607 of 2020 Judgment of: BROMBERG J Date of judgment: 27 May 2021 Catchwords: NEGLIGENCE – representative proceeding seeking a declaration that a duty of care be recognised and an injunction be granted restraining its breach – Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) – novel duty of care – whether the Minister for the Environment owes Australian children a duty of care when approving under s 130 and s 133 of the EPBC Act the extraction of coal from a coal mine – risk of injury from climate change – claim that CO2 emissions from coal to be extracted will contribute to increased global surface temperatures leading to extreme weather events and consequent exposure of Australian children to the increased risk of personal injury, property damage and economic loss – discussion of applicable legal principles for ascertaining whether a novel duty of care exists – salient features approach adopted – whether feared harm reasonably foreseeable – whether the Minister has control, responsibility and knowledge in relation to foreseeable harm – extent of children’s vulnerability to feared harm – whether recognised relationships between Minister and children exist including by reference to parens patriae doctrine – discussion of coherence in the law – whether imposition of liability in negligence is incoherent with statutory discretion provided to Minister under s 130 and -

Diversity and Inclusion Annual Report

Diversity and Inclusion Annual Report 2020 INTRODUCTION A message from Global Managing Partner Global Head of Diversity and Inclusion I am delighted to share Ashurst’s Diversity and Inclusion Whilst it has been an extremely busy and rewarding annual report for 2020, outlining our achievements, activities 12 months when we look at progress the firm has made, Contents and impact in this space. 2020 has also been a year of enormous disruption and unrest. COVID-19 has impacted the way we live, work and A message from 3 2020 was undoubtedly a difficult year for us all, with the interact including the way we have traditionally approached impact of Covid-19 being felt across the world. Despite Diversity and Inclusion at Ashurst. This year has required Our year in numbers 4 the challenges that the pandemic brought upon us, I am us to step back and look at how we can effectively impact very proud of how the Ashurst community supported one change in a virtual world whilst still building a strong sense Our focus 5 another and built a stronger sense of community during this of inclusion and community. time. From the launch of a number of wellbeing initiatives, Covid-19 and its impact 6 and our LGBTI+ Inclusive Language Guide, to the creation of Each of us have experienced challenging aspects of COVID-19 a number of new D&I employee networks and new client whether that is managing work and caring responsibilities Our targets 8 collaboration opportunites – our focus on putting diversity or feeling isolated in lockdown. -

Recent Developments in Unfair Contract Terms

Ashurst Australia 30 April 2013 Competition Law News Recent developments in unfair contract terms WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW The ACCC has now commenced two Federal Court cases concerning unfair terms. It has also identified eight specific types of contract terms which it considers contravene the unfair contracts regime under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), and signalled its intention to undertake enforcement action in relation to unfair terms. WHAT YOU NEED TO DO Consider whether the terms in your standard form consumer contracts, including any terms of the type identified by the ACCC, comply with the ACL. Watch this space: the outcome of the current proceedings will provide critical guidance on this as yet untested regime. ACCC moves to enforce the unfair Recap - the law concerning unfair contract terms regime contract terms The ACCC is currently conducting Federal Court The unfair contract terms laws apply to standard form proceedings concerning unfair contract terms against consumer contracts entered into, varied, or renewed Advanced Medical Institute Pty Ltd, and commenced a on or after 1 July 2010. separate proceeding against ByteCard Pty Limited last week. "Standard form consumer contracts" The ACCC also recently released the Unfair Contract A "consumer contract" is a contract for the supply Terms – Industry Review Outcomes Report (Report), of goods or services (or the sale or grant of an interest which arose out of its review of potentially unfair in land) to an individual whose acquisition of the good, contract terms used in the airline, service or interest is wholly or predominantly for telecommunications, fitness and vehicle rental personal, domestic or household use or consumption.