"Viva La Vida"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

K Street Union Song List

TOP 40 / DANCE 24 KARAT MAGIC Bruno Mars DOMINO Jesse J AIN’T IT FUN Paramore DON’T YOU WORRY CHILD Swedish AMERICAN BOY Estelle House Mafia ELECTRICITY Dua Lipa ANIMAL Neon Trees EX’S & OH’S Elle King BANG BANG Arianna Grande FEEL IT STILL Portugal. The Man BEST DAY OF MY LIFE American Authors FEEL SO CLOSE Calvin Harris BEYOND Leon Bridges FIREWORK Katy Perry BLAME Calvin Harris GET LUCKY Daft Punk BLURRED LINES Robin Thicke GLAD YOU CAME The Wanted BUDAPEST George Ezra GOOD AS HELL Lizzo CAKE BY THE OCEAN DNCE HAND CLAP Fitz and the Tantrums CALL ME MAYBE Carly Rae Jepsen HAPPY Pharrell CAN’T STOP THE FEELING Justin HAVANA Camila Cabello Timberlake HELLO Adele CHEAP THRILLS Sia HEY YA! Outkast CLOSER The Chainsmokers HIGH HOPES Panic at the Disco COUNTING STARS One Republic HOLD MY HAND Jess Glynn CRAZY Gnarles Barkley HOME Edward Sharpe and the CRAZY IN LOVE Beyoncé Magnetics ***Song list subject to change without notice*** !1 of !7 TOP 40 / DANCE SMILE Katy Perry STARSHIPS Nicki Minaj STAY THE NIGHT Paramore I WILL ALWAYS BE YOURS Ben STUPID LOVE Lady Gaga Rector STYLE Taylor Swift JUST DANCE Lady Gaga SUCKER Jonas Brothers LIPS ARE MOVIN Meghan Trainor SUGAR Maroon 5 LITTLE TALKS Of Monsters and Men THE MIDDLE Marren Morris & Zedd LOCKED OUT OF HEAVEN Bruno THERE’S NOTHING HOLDING ME Mars BACK Shawn Mendez LONELY BOY Black Keys THINKING OUT LOUD Ed Sheeran LOVE ON TOP Beyoncé TREASURE Bruno Mars ME TOO Meghan Trainor RAISE YOUR GLASS Pink MOVES LIKE JAGGER Maroon 5 RUDE Magic! NO ROOTS Alice Merton SHAKE IT OFF Taylor Swift OCEAN -

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

Eddie B's Wedding Songs

ƒƒƒƒƒƒ ƒƒƒƒƒƒ Eddie B. & Company Presents Music For… Bridal Party Introductions Cake Cutting 1. Beautiful Day . U2 1. 1,2,3,4 (I Love You) . Plain White T’s 2. Best Day Of My Life . American Authors 2. Accidentally In Love . Counting Crows 3. Bring Em’Out . T.I. 3. Ain’t That A Kick In The Head . Dean Martin 4. Calabria . Enur & Natasja 4. All You Need Is Love . Beatles 5. Celebration . Kool & The Gang 5. Beautiful Day . U2 6. Chelsea Dagger . Fratellis 6. Better Together . Jack Johnson 7. Crazy In Love . Beyonce & Jay Z 7. Build Me Up Buttercup . Foundations 8. Don’t Stop The Party . Pitbull 8. Candyman . Christina Aguilera 9. Enter Sandman . Metalica 9. Chapel of Love . Dixie Cups 10. ESPN Jock Jams . Various Artists 10. Cut The Cake . Average White Bank 11. Everlasting Love . Carl Carlton 11. Everlasting Love . Carl Carlton & Gloria Estefan 12. Eye Of The Tiger . Survivor 12. Everything . Michael Buble 13. Feel So Close . Calvin Harris 13. Grow Old With You . Adam Sandler 14. Feel This Moment . Pitt Bull & Christina Aguilera 14. Happy Together . Turtles 15. Finally . Ce Ce Peniston 15. Hit Me With Your Best Shot . Pat Benatar 16. Forever . Chris Brown 16. Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You) . James Taylor 17. Get Ready For This . 2 Unlimited 17. I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) Four Tops 18. Get The Party Started . Pink 18. I Got You Babe . Sonny & Cher 19. Give Me Everything Tonight . Pitbull & Ne-Yo 19. Ice Cream . Sarah McLachlan 20. Gonna Fly Now . -

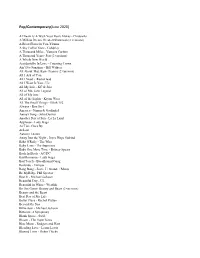

Quartet March2020

Pop/Contemporary (June 2020) A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes - Cinderella A Million Dream Greatest Showman (2 versions) A River Flows in You-Yiruma A Sky Full of Stars - Coldplay A Thousand Miles - Vanessa Carlton A Thousand Years- Peri (2 versions) A Whole New World Accidentally In Love - Counting Crows Ain't No Sunshine - Bill Withers All About That Bass- Trainor (2 versions) All I Ask of You All I Need - RadioHead All I Want Is You - U2 All My Life - KC & Jojo All of Me- John Legend All of My love All of the Lights - Kayne West All The Small Things - Blink 182 Always - Bon Jovi America - Simon & Garfunkel Annie's Song - John Denver Another Day of Sun - La La Land Applause - Lady Gaga As Time Goes By At Last Autumn Leaves Away Into the Night - Joyce Hope Siskind Baba O'Reily - The Who Baby Love - The Supremes Baby One More Time - Britney Spears Back In Black - AC/DC Bad Romance - Lady Gaga Bad Touch - Bloodhound Gang Bailando - Enrique Bang Bang - Jessie J / Grande / Minaj Be MyBaby- Phil Spector Beat It - Michael Jackson Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful in White - Westlife Be Our Guest- Beauty and Beast (2 versions) Beauty and the Beast Best Day of My Life Better Place - Rachel Platten Beyond the Sea Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Bittersweet Symphony Blank Space - Swift Bloom - The Paper Kites Blue Moon - Rodgers and Hart Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Bohemian Rapsody-Queen Book of Days - Enya Book of Love - Peter Gabriel Boom Clap - Charli XCX Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Budapest - Geo Ezra Buddy Holly- -

Encore Songlist

west coast music Encore Please find attached the Encore Band song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need to have your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, F/D Dance, etc) FOUR WEEKS prior to your event so that we can confirm the band will be able to perform the song(s) and so that we have time to locate sheet music and audio of the song(s). In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is needed, this gives us time to properly prepare the music. Clients are not obligated to submit a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and/or avoided. If you desire the highest degree of control (asking the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we would ask for a minimum 80 requests from the band’s songlist. Please feel free to call us at the office should you have any questions. – West Coast Music SONGLIST: At Last – Etta James 1,2,3,4 – Plain White T’s Baby Got Back – Sir Mix A Lot 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Back at One – Boyz II Men A Thousand Years – Christina Bad Day – Daniel Powter Perri Ballad Of John & Yoko Ain’t too Proud to Beg – Bamboleo – Gipsy Kings Temptations Bang my Head – David Guetta/Sia Adventure of a Lifetime – Beast of Burden – Rolling Stones Coldplay Beautiful Day – U2 After All – Peter Cetera/Cher -

Hello Adele Saxophone Quintet Sheet Music

Hello Adele Saxophone Quintet Sheet Music Download hello adele saxophone quintet sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of hello adele saxophone quintet sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2751 times and last read at 2021-09-30 19:46:22. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of hello adele saxophone quintet you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Ensemble: Saxophone Quintet, Woodwind Quintet Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Someone Like You By Adele Saxophone Quartet Satb Someone Like You By Adele Saxophone Quartet Satb sheet music has been read 2586 times. Someone like you by adele saxophone quartet satb arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 20:25:07. [ Read More ] Hello Adele Clarinet Quintet Hello Adele Clarinet Quintet sheet music has been read 3994 times. Hello adele clarinet quintet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 19:47:14. [ Read More ] Someone Like You By Adele Solo Saxophone In Eb Bb Someone Like You By Adele Solo Saxophone In Eb Bb sheet music has been read 2531 times. Someone like you by adele solo saxophone in eb bb arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 17:26:56. [ Read More ] Adele Rolling In The Deep For Brass Quintet Adele Rolling In The Deep For Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 3961 times. -

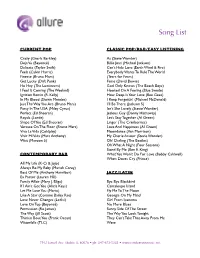

Allure Song List

Song List CURRENT POP CLASSIC POP/R&B/EASY LISTENING Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) As (Steve Wonder) Deja Vu (Beyoncé) Billie Jean (Michael Jackson) Delicate (Taylor Swift) Can’t Hide Love (Earth Wind & Fire) Feels (Calvin Harris) Everybody Wants To Rule The World Finesse (Bruno Mars) (Tears for Fears) Get Lucky (Daft Punk) Fame (David Bowie) Ho Hey (The Lumineers) God Only Knows (The Beach Boys) I Feel It Coming (The Weeknd) Hooked On A Feeling (Blue Swede) Ignition Remix (R. Kelly) How Deep Is Your Love (Bee Gees) In My Blood (Shawn Mendes) I Keep Forgettin’ (Michael McDonald) Just The Way You Are (Bruno Mars) I’ll Be There (Jackson 5) Party In The USA (Miley Cyrus) Isn’t She Lovely (Stevie Wonder) Perfect (Ed Sheeran) Jealous Guy (Donny Hathaway) Royals (Lorde) Let’s Stay Together (Al Green) Shape Of You (Ed Sheeran) Linger (The Cranberries) Versace On The Floor (Bruno Mars) Love And Happiness (Al Green) Viva La Vida (Coldplay) Moondance (Van Morrison) Vivir Mi Vida (Marc Anthony) My Cherie Amour (Stevie Wonder) Wait (Maroon 5) Oh! Darling (The Beatles) Oh What A Night (Four Seasons) Stand By Me (Ben E. King) CONTEMPORARY R&B What You Won’t Do For Love (Bobby Caldwell) When Doves Cry (Prince) All My Life (K-Ci & JoJo) Always Be My Baby (Mariah Carey) Best Of Me (Anthony Hamilton) JAZZ/LATIN Ex Factor (Lauren Hill) Family Affair (Mary J. Blige) Bye Bye Blackbird If I Ain’t Got You (Alicia Keys) Cantaloupe Island Let Me Love You (Mario) Fly Me To The Moon Like A Star (Corinne Bailey Rae) Georgia On My Mind Love Never Changes (Ledisi) Girl From Ipanema Love On Top (Beyoncé) No More Blues Permission (Ro James) Sunny Side Of The Street The Way (Jill Scott) The Way You Look Tonight Thinkin Bout You (Frank Ocean) They Can’t Take That Away From Me Waterfalls (TLC) Wave 7912 Lowell Ave. -

Adam David Song List

ADAM DAVID SONG LIST Artist Song 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Adelle Hello Rolling In The Deep Someone Like You Allen Stone Is This Love Unaware Amy Winehouse Back To Black Rehab Valerie Avicii Wake Me Up Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Aint No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Black Sabbath War Pigs Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone Bob Marley Dont Worry About A Thing I Shot The Sheriff No Woman No Cry Stir It Up Bob Seger Turn The Page Night Moves Bobby Mcferrin Dont Worry Be Happy Bon Jovi Livin On A Prayer Bruno Mars Grenade When I Was Your Man Bryan Adams Summer Of 69 Carlos Santana Maria Maria Cheap Trick I Want You To Want Me Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Citizen Cope Sideways Coldplay Clocks Viva La Vida Yellow Counting Crows Mr Jones Cream White Room Creedence Clearwater Revival Have You Ever Seen The Rain David Guetta Titanium Dobie Gray Drift Away Don Mclean American Pie Eagles Hotel California Take It Easy Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Eric Clapton Change The World Layla Nobody Knows You When Youre Down And Out Tears In Heaven Etta James At Last Extreme More Than Words Fleetwood Mac Landslide Foreigner Cold As Ice Foster The People Pumped Up Kicks Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The Moon Girl From Ipanema Fun We Are Young Gavin Degraw I Dont Want To Be Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gorillaz Clint Eastwood Gotye Somebody That I Used To Know Grateful Dead Casey Jones Franklins Tower Green Day Good Riddance Time Of Your Life Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O Mine Live Incubus Drive Pardon Me Israel Kamakawiwo'ole Somewhere Over The Rainbow What A Wonderful -

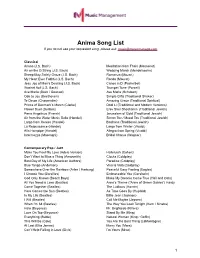

Anima Song List If You Do Not See Your Requested Song, Please Ask: [email protected]

Anima Song List If you do not see your requested song, please ask: [email protected] Classical Arioso (J.S. Bach) Meditation from Thais (Massenet) Air on the G String (J.S. Bach) Wedding March (Mendelssohn) Sheep May Safely Graze (J.S. Bach) Romanza (Mozart) My Heart Ever Faithful (J.S. Bach) Rondo (Mouret) Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring (J.S. Bach) Canon in D (Pachelbel) Wachet Auf (J.S. Bach) Trumpet Tune (Purcell) Ave Maria (Bach / Gounod) Ave Maria (Schubert) Ode to Joy (Beethoven) Simple Gifts (Traditional Shaker) Te Deum (Charpentier) Amazing Grace (Traditional Spiritual) Prince of Denmark’s March (Clarke) Dodi Li (Traditional and Modern Versions) Flower Duet (Delibes) Erev Shel Shoshanim (Traditional Jewish) Panis Angelicus (Franck) Jerusalem of Gold (Traditional Jewish) Air from the Water Music Suite (Handel) Simon Tov / Mazel Tov (Traditional Jewish) Largo from Xerxes (Handel) Bashana (Traditional Jewish) La Rejoussance (Handel) Largo from Winter (Vivaldi) Alla Hornpipe (Handel) Allegro from Spring (Vivaldi) Intermezzo (Mascagni) Bridal Chorus (Wagner) Contemporary Pop / Jazz Make You Feel My Love (Adele Version) Halleluiah (Cohen) Don’t Want to Miss a Thing (Aerosmith) Clocks (Coldplay) Best Day of My Life (American Authors) Paradise (Coldplay) Blue Tango (Anderson) Viva la Vida (Coldplay) Somewhere Over the Rainbow (Arlan / Harburg) Peaceful Easy Feeling (Eagles) I Choose You (Bareilles) Embraceable You (Gershwin) God Only Knows (Beach Boys) Make My Dreams Come True (Hall and Oats) All You Need is Love (Beatles) Anne’s Theme (“Anne of Green Gables”) Hardy Come Together (Beatles) The Ludlows (Horner) Here Comes the Sun (Beatles) As Time Goes By (Hupfeld) In My Life (Beatles) Billie Jean (Jackson) I Will (Beatles) Call Me Maybe (Jepsen) When I’m 64 (Beatles) The Way You Look Tonight (Kern / Sinatra) Halo (Beyonce) Mr. -

Re-Thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo

Re-thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo Regina F. Bartolone A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: Dr. Martine Antle (advisor) Dr. Marsha Collins (reader) Dr. Maria DeGuzmán (reader) Dr. Dominque Fisher (reader) Dr. Diane Leonard (reader) Abstract Regina F.Bartolone Re-Thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo (Under the direction of Dr. Martine Antle) This dissertation is a cross-cultural examination of the creation and the socio- cultural implications of the languages of pain in the works of French author, Marguerite Duras and Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo. Recent studies have determined that discursive communication is insufficient in expressing one’s pain. In particular, Elaine Scarry maintains that pain destroys language and that its victims must rely on the vocabulary of other cultural spheres in order to express their pain. The problem is that neither Scarry nor any other Western pain scholar can provide an alternative to discursive language to express pain. This study claims that both artists must work beyond their own cultural registers in order to give their pain a language. In the process of expressing their suffering, Duras and Kahlo subvert traditional literary and artistic conventions. Through challenging literary and artistic forms, they begin to re-think and ultimately re-define the way their readers and viewers understand feminine subjectivity, colonial and wartime occupation, personal tragedy, the female body, Christianity and Western hegemony. -

{PDF} Frida Kahlo: the Paintings

FRIDA KAHLO: THE PAINTINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hayden Herrera | 272 pages | 04 Jun 2002 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780060923198 | English | New York, NY, United States 20 Most Famous Frida Kahlo Paintings - Artist PopLab Kahlo discussed What the Water Gave Me with the Manhattan gallery owner Julien Levy, and suggested that it was a sad piece that mourned the loss of her childhood. Perhaps the strangled figure at the centre is representative of the inner emotional torments experienced by Kahlo herself. It is clear from the conversation that the artist had with Levy, that Kahlo was aware of the philosophical implications of her work. In an interview with Herrera, Levy recalls, in 'a long philosophical discourse, Kahlo talked about the perspective of herself that is shown in this painting'. He further relays that 'her idea was about the image of yourself that you have because you do not see your head. The head is something that is looking, but is not seen. It is what one carries around to look at life with. As well as an inclusion of death by strangulation in the centre of the water, there is also a labia-like flower and a cluster of pubic hair painted between Kahlo's legs. The work is quite sexual while also showing preoccupation with destruction and death. The motif of the bathtub in art is one that has been popular since Jacques-Louis David's The Death of Marat , and was later taken up many different personalities such as Francesca Woodman and Tracey Emin. This double self-portrait is one of Kahlo's most recognized compositions, and is symbolic of the artist's emotional pain experienced during her divorce from Rivera. -

The Influence of Mexican Retablo and Ex-Voto Paintings on Her Art Author(S): María A

Woman's Art, Inc. Frida Kahlo's Spiritual World: The Influence of Mexican Retablo and Ex-voto Paintings on Her Art Author(s): María A. Castro-Sethness Source: Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Autumn, 2004 - Winter, 2005), pp. 21-24 Published by: Woman's Art, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3566513 . Accessed: 29/09/2011 09:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Woman's Art, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Woman's Art Journal. http://www.jstor.org I ; : : I I : j ; 'L FRIDA KAHLO'SSPIRITUAL WORLD The Influence of Mexican Retablo and Ex-voto Paintings on Her Art By Maria A. Castro-Sethness rida Kahlo's(1907-54) incorporationin her art of Mexican Kahlo's fascination with the power and symbolic content of her retablo and ex-voto images exhibits a complex dialectic be- beloved images that, in a magical way, transcended her own space tween the social dimension of these art forms, their intimate and became re-elaborations of a utopian dream. relationship to religion, the creation of art, the struggle to create life, Gloria Fraser Giffords distinguishes the European retablo from and the inevitability of death.