Hydrothermal Vents and Cold Seeps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inferences on Potential Seamount Locations from Mid-Resolution

T. Morato and D. Pauly (eds.), Seamounts: Biodiversity and Fisheries, Page 7 INFERENCES ON POTENTIAL SEAMOUNT LOCATIONS FROM MID- RESOLUTION BATHYMETRIC DATA Adrian Kitchingman and Sherman Lai Fisheries Centre, The University of British Columbia. 2259 Lower Mall, Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z4, Canada [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT Seamounts are underwater volcanoes that did not grow tall enough to break to the sea surface and turn into islands. Once formed, seamounts tend to gradually sink under their own weight and the subsidence of the lithosphere. The ocean floor is littered with these former seamounts, here called ‘seamounds’. Seamounts occur throughout the world's oceans, but their number (which may surpass 50,000) is difficult to estimate, even roughly, because it depends on the resolution of the bathymetric map used and the specific definition of a seamount used, i.e., the limits used to distinguish between seamounts and seamounds. Here, the locations of a subset of the seamounts of the world were identified using two algorithms relying on the depth differences between adjacent cells of a digital global elevation map distributed by the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA). The overlap of both algorithms resulted in a set of about 14,000 seamounts, but a different number would have been found had we used different thresholds. Known seamount locations supplied by NOAA and SeamountsOnline (http://seamounts.sdsc.edu) were compared against the corresponding seamounts located by the study, which led to some degree of ground-truthing. The coordinates of the seamounts identified in this study are available on the CD-ROM attached to this report, and on http://www.seaaroundus.org. -

7.014 Handout PRODUCTIVITY: the “METABOLISM” of ECOSYSTEMS

7.014 Handout PRODUCTIVITY: THE “METABOLISM” OF ECOSYSTEMS Ecologists use the term “productivity” to refer to the process through which an assemblage of organisms (e.g. a trophic level or ecosystem assimilates carbon. Primary producers (autotrophs) do this through photosynthesis; Secondary producers (heterotrophs) do it through the assimilation of the organic carbon in their food. Remember that all organic carbon in the food web is ultimately derived from primary production. DEFINITIONS Primary Productivity: Rate of conversion of CO2 to organic carbon (photosynthesis) per unit surface area of the earth, expressed either in terns of weight of carbon, or the equivalent calories e.g., g C m-2 year-1 Kcal m-2 year-1 Primary Production: Same as primary productivity, but usually expressed for a whole ecosystem e.g., tons year-1 for a lake, cornfield, forest, etc. NET vs. GROSS: For plants: Some of the organic carbon generated in plants through photosynthesis (using solar energy) is oxidized back to CO2 (releasing energy) through the respiration of the plants – RA. Gross Primary Production: (GPP) = Total amount of CO2 reduced to organic carbon by the plants per unit time Autotrophic Respiration: (RA) = Total amount of organic carbon that is respired (oxidized to CO2) by plants per unit time Net Primary Production (NPP) = GPP – RA The amount of organic carbon produced by plants that is not consumed by their own respiration. It is the increase in the plant biomass in the absence of herbivores. For an entire ecosystem: Some of the NPP of the plants is consumed (and respired) by herbivores and decomposers and oxidized back to CO2 (RH). -

Hydrothermal Vents. Teacher's Notes

Hydrothermal Vents Hydrothermal Vents. Teacher’s notes. A hydrothermal vent is a fissure in a planet's surface from which geothermally heated water issues. They are usually volcanically active. Seawater penetrates into fissures of the volcanic bed and interacts with the hot, newly formed rock in the volcanic crust. This heated seawater (350-450°) dissolves large amounts of minerals. The resulting acidic solution, containing metals (Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu) and large amounts of reduced sulfur and compounds such as sulfides and H2S, percolates up through the sea floor where it mixes with the cold surrounding ocean water (2-4°) forming mineral deposits and different types of vents. In the resulting temperature gradient, these minerals provide a source of energy and nutrients to chemoautotrophic organisms that are, thus, able to live in these extreme conditions. This is an extreme environment with high pressure, steep temperature gradients, and high concentrations of toxic elements such as sulfides and heavy metals. Black and white smokers Some hydrothermal vents form a chimney like structure that can be as 60m tall. They are formed when the minerals that are dissolved in the fluid precipitates out when the super-heated water comes into contact with the freezing seawater. The minerals become particles with high sulphur content that form the stack. Black smokers are very acidic typically with a ph. of 2 (around that of vinegar). A black smoker is a type of vent found at depths typically below 3000m that emit a cloud or black material high in sulphates. White smokers are formed in a similar way but they emit lighter-hued minerals, for example barium, calcium and silicon. -

Cold Seep Benthic Communities in Japan Subduction Zones: Spatial Organization, Trophic Strategies and Evidence for Temporal Evolution*

MARINE ECOLOGY - PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 40: 115-126. 1987 Published October 7 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Cold seep benthic communities in Japan subduction zones: spatial organization, trophic strategies and evidence for temporal evolution* S. Kim Juniper", Myriam Sibuet IFREMER, Centre de Brest. BP 337. F-29273 Brest Cedex. France ABSTRACT: Submersible exploration of the Japan subduction zones has revealed benthic communities dominated by clams (Calyptogena spp.) around sed~mentporewater seeps at depths from 3850 to 6000 m. Photographic and video records were used to produce microcartographlc reconstructions of 3 contrasting cold seep sites. Spatial and abundance relations of megafauna lead us to propose several hypotheses regard~ngthe ecological functioning of these cold seep communities. We dlst~nguish between the likely direct use of reducing substances in venting fluids by Calyptogena-bacteria symbioses and indirect usage by accompanying abyssal species not known to harbour symbionts. Microdistribution and known or presumed feedmg modes of the accompanying species indicate 2 different sources of organic matter enrichment within cold seep sites: organic debris originating from bivalve colonies, and enrichment of extensive areas of surrounding surface sediments where weaker, more hffuse porewater seepage may support chemosynthetic production by free-living bacteria. The occurrence of colony-like groupings of empty Calyptogena valves indicates that cold seeps are ephemeral, with groups of living clams, mixed living and dead clams, and empty dissolving shells marlung the course of a cycle of porewater venting and offering clues to the recent history of cold seep activity. INTRODUCTION al. 1985). One of the bivalve species from this area has been shown to harbour symbiotic bacteria in its gill The discovery of deep-sea hydrothermal vents has tissue and to oxidise methane (Childress et al. -

Introduction to Co2 Chemistry in Sea Water

INTRODUCTION TO CO2 CHEMISTRY IN SEA WATER Andrew G. Dickson Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii Monthly Average Carbon Dioxide Concentration Data from Scripps CO Program Last updated August 2016 2 ? 410 400 390 380 370 2008; ~385 ppm 360 350 Concentration (ppm) 2 340 CO 330 1974; ~330 ppm 320 310 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 Year EFFECT OF ADDING CO2 TO SEA WATER 2− − CO2 + CO3 +H2O ! 2HCO3 O C O CO2 1. Dissolves in the ocean increase in decreases increases dissolved CO2 carbonate bicarbonate − HCO3 H O O also hydrogen ion concentration increases C H H 2. Reacts with water O O + H2O to form bicarbonate ion i.e., pH = –lg [H ] decreases H+ and hydrogen ion − HCO3 and saturation state of calcium carbonate decreases H+ 2− O O CO + 2− 3 3. Nearly all of that hydrogen [Ca ][CO ] C C H saturation Ω = 3 O O ion reacts with carbonate O O state K ion to form more bicarbonate sp (a measure of how “easy” it is to form a shell) M u l t i p l e o b s e r v e d indicators of a changing global carbon cycle: (a) atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) from Mauna Loa (19°32´N, 155°34´W – red) and South Pole (89°59´S, 24°48´W – black) since 1958; (b) partial pressure of dissolved CO2 at the ocean surface (blue curves) and in situ pH (green curves), a measure of the acidity of ocean water. -

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future As more and more states are incorporating projections of sea-level rise into coastal planning efforts, the states of California, Oregon, and Washington asked the National Research Council to project sea-level rise along their coasts for the years 2030, 2050, and 2100, taking into account the many factors that affect sea-level rise on a local scale. The projections show a sharp distinction at Cape Mendocino in northern California. South of that point, sea-level rise is expected to be very close to global projections; north of that point, sea-level rise is projected to be less than global projections because seismic strain is pushing the land upward. ny significant sea-level In compliance with a rise will pose enor- 2008 executive order, mous risks to the California state agencies have A been incorporating projec- valuable infrastructure, devel- opment, and wetlands that line tions of sea-level rise into much of the 1,600 mile shore- their coastal planning. This line of California, Oregon, and study provides the first Washington. For example, in comprehensive regional San Francisco Bay, two inter- projections of the changes in national airports, the ports of sea level expected in San Francisco and Oakland, a California, Oregon, and naval air station, freeways, Washington. housing developments, and sports stadiums have been Global Sea-Level Rise built on fill that raised the land Following a few thousand level only a few feet above the years of relative stability, highest tides. The San Francisco International Airport (center) global sea level has been Sea-level change is linked and surrounding areas will begin to flood with as rising since the late 19th or to changes in the Earth’s little as 40 cm (16 inches) of sea-level rise, a early 20th century, when climate. -

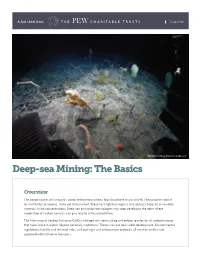

Deep-Sea Mining: the Basics

A fact sheet from June 2018 NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research Deep-sea Mining: The Basics Overview The deepest parts of the world’s ocean feature ecosystems found nowhere else on Earth. They provide habitat for multitudes of species, many yet to be named. These vast, lightless regions also possess deposits of valuable minerals in rich concentrations. Deep-sea extraction technologies may soon develop to the point where exploration of seabed minerals can give way to active exploitation. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is charged with formulating and enforcing rules for all seabed mining that takes place in waters beyond national jurisdictions. These rules are now under development. Environmental regulations, liability and financial rules, and oversight and enforcement protocols all must be written and approved within three to five years. Figure 1 Types of Deep-sea Mining Production support vessel Return pipe Riser pipe Cobalt Seafloor massive Polymetallic crusts sulfides nodules Subsurface plumes 800-2,500 from return water meters deep Deposition 1,000-4,000 meters deep 4,000-6,500 meters deep Cobalt-rich Localized plumes Seabed pump Ferromanganeseferromanganese from cutting crusts Seafloor production tool Nodule deposit Massive sulfide deposit Sediment Source: New Zealand Environment Guide © 2018 The Pew Charitable Trusts 2 The legal foundations • The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Also known as the Law of the Sea Treaty, UNCLOS is the constitutional document governing mineral exploitation on the roughly 60 percent of the world seabed that lies beyond national jurisdictions. UNCLOS took effect in 1994 upon passage of key enabling amendments designed to spur commercial mining. -

Relationships Between Net Primary Production, Water Transparency, Chlorophyll A, and Total Phosphorus in Oak Lake, Brookings County, South Dakota

Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science, Vol. 92 (2013) 67 RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN NET PRIMARY PRODUCTION, WATER TRANSPARENCY, CHLOROPHYLL A, AND TOTAL PHOSPHORUS IN OAK LAKE, BROOKINGS COUNTY, SOUTH DAKOTA Lyntausha C. Kuehl and Nels H. Troelstrup, Jr.* Department of Natural Resource Management South Dakota State University Brookings, SD 57007 *Corresponding author email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Lake trophic state is of primary concern for water resource managers and is used as a measure of water quality and classification for beneficial uses. Secchi transparency, total phosphorus and chlorophyll a are surrogate measurements used in the calculation of trophic state indices (TSI) which classify waters as oligotrophic, mesotrophic, eutrophic or hypereutrophic. Yet the relationships between these surrogate measurements and direct measures of lake productivity vary regionally and may be influenced by external factors such as non-algal tur- bidity. Prairie pothole basins, common throughout eastern South Dakota and southwestern Minnesota, are shallow glacial lakes subject to frequent winds and sediment resuspension. Light-dark oxygen bottle methodology was employed to evaluate vertical planktonic production within an eastern South Dakota pothole basin. Secchi transparency, total phosphorus and planktonic chlorophyll a were also measured from each of three basin sites at biweekly intervals throughout the 2012 growing season. Secchi transparencies ranged between 0.13 and 0.25 meters, corresponding to an average TSISD value of 84.4 (hypereutrophy). Total phosphorus concentrations ranged between 178 and 858 ug/L, corresponding to an average TSITP of 86.7 (hypereutrophy). Chlorophyll a values corresponded to an average TSIChla value of 69.4 (transitional between eutrophy and hypereutro- phy) and vertical production profiles yielded areal net primary productivity val- ues averaging 288.3 mg C∙m-2∙d-1 (mesotrophy). -

EXPLORING DEEP SEA HYDROTHERMAL VENTS on EARTH and OCEAN WORLDS. P. Sobron1,2, L. M. Barge3, the Invader Team. 1Impossible Sensing, St

52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2021 (LPI Contrib. No. 2548) 2505.pdf EXPLORING DEEP SEA HYDROTHERMAL VENTS ON EARTH AND OCEAN WORLDS. P. Sobron1,2, L. M. Barge3, the InVADER Team. 1Impossible Sensing, St. Louis, MO ([email protected]) 2SETI Institute, Mtn. View, CA, , 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA The Mission: InVADER (In-situ Vent Analysis precipitates showing exposed minerals and organic Divebot for Exobiology Research, Figure 4.1, content. The UNOLS ROV will use our coring tool and https://invader-mission.org/) is NASA’s most advanced its own manipulator and cameras to take ground truth subsea sensing payload, a tightly integrated imaging and samples as part of the InVADER deplotment. laser Raman spectroscopy/laser-induced breakdown In contrast to existing methods, InVADER allows spectroscopy/laser induced native fluorescence in-situ, autonomous, non-destructive measurements of instrument capable of in-situ, rapid, long-term these vent characteristics. InVADER will fill these gaps, underwater analyses of vent fluid and precipitates. and advance readiness in vent exploration on Earth and Such analyses are critical for finding and studying Ocean Worlds by simplifying operational strategies for life and life’s precursors at vent systems on Ocean identifying and characterizing seafloor environments. Worlds. To demonstrate the scientific potential and We will use statistical analysis tools for the fusion of functionality of the instrument, in July 2021 our team multi-sensor datasets, and develop real-time science will deploy InVADER on the Ocean Observatories data evaluation and payload control routines to Initiative’s (OOI) Regional Cabled Array (RCA), a establish, and then validate, adaptive science operations power/data distribution network off the Oregon coast, at strategies that maximize science return in a mission-like the underwater hydrothermal systems of Axial scenario. -

Significant Dissipation of Tidal Energy in the Deep Ocean Inferred from Satellite Altimeter Data

letters to nature 3. Rein, M. Phenomena of liquid drop impact on solid and liquid surfaces. Fluid Dynamics Res. 12, 61± water is created at high latitudes12. It has thus been suggested that 93 (1993). much of the mixing required to maintain the abyssal strati®cation, 4. Fukai, J. et al. Wetting effects on the spreading of a liquid droplet colliding with a ¯at surface: experiment and modeling. Phys. Fluids 7, 236±247 (1995). and hence the large-scale meridional overturning, occurs at 5. Bennett, T. & Poulikakos, D. Splat±quench solidi®cation: estimating the maximum spreading of a localized `hotspots' near areas of rough topography4,16,17. Numerical droplet impacting a solid surface. J. Mater. Sci. 28, 963±970 (1993). modelling studies further suggest that the ocean circulation is 6. Scheller, B. L. & Bous®eld, D. W. Newtonian drop impact with a solid surface. Am. Inst. Chem. Eng. J. 18 41, 1357±1367 (1995). sensitive to the spatial distribution of vertical mixing . Thus, 7. Mao, T., Kuhn, D. & Tran, H. Spread and rebound of liquid droplets upon impact on ¯at surfaces. Am. clarifying the physical mechanisms responsible for this mixing is Inst. Chem. Eng. J. 43, 2169±2179, (1997). important, both for numerical ocean modelling and for general 8. de Gennes, P. G. Wetting: statics and dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 57, 827±863 (1985). understanding of how the ocean works. One signi®cant energy 9. Hayes, R. A. & Ralston, J. Forced liquid movement on low energy surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 159, 429±438 (1993). source for mixing may be barotropic tidal currents. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Biodiversity and Trophic Ecology of Hydrothermal Vent Fauna Associated with Tubeworm Assemblages on the Juan De Fuca Ridge

Biogeosciences, 15, 2629–2647, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-2629-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Biodiversity and trophic ecology of hydrothermal vent fauna associated with tubeworm assemblages on the Juan de Fuca Ridge Yann Lelièvre1,2, Jozée Sarrazin1, Julien Marticorena1, Gauthier Schaal3, Thomas Day1, Pierre Legendre2, Stéphane Hourdez4,5, and Marjolaine Matabos1 1Ifremer, Centre de Bretagne, REM/EEP, Laboratoire Environnement Profond, 29280 Plouzané, France 2Département de sciences biologiques, Université de Montréal, C.P. 6128, succursale Centre-ville, Montréal, Québec, H3C 3J7, Canada 3Laboratoire des Sciences de l’Environnement Marin (LEMAR), UMR 6539 9 CNRS/UBO/IRD/Ifremer, BP 70, 29280, Plouzané, France 4Sorbonne Université, UMR7144, Station Biologique de Roscoff, 29680 Roscoff, France 5CNRS, UMR7144, Station Biologique de Roscoff, 29680 Roscoff, France Correspondence: Yann Lelièvre ([email protected]) Received: 3 October 2017 – Discussion started: 12 October 2017 Revised: 29 March 2018 – Accepted: 7 April 2018 – Published: 4 May 2018 Abstract. Hydrothermal vent sites along the Juan de Fuca community structuring. Vent food webs did not appear to be Ridge in the north-east Pacific host dense populations of organised through predator–prey relationships. For example, Ridgeia piscesae tubeworms that promote habitat hetero- although trophic structure complexity increased with ecolog- geneity and local diversity. A detailed description of the ical successional stages, showing a higher number of preda- biodiversity and community structure is needed to help un- tors in the last stages, the food web structure itself did not derstand the ecological processes that underlie the distribu- change across assemblages.