Understanding the Business of Popular Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Songwriting Cheatsheet

Songwriting Cheatsheet If you study the charts, you’ll realize that great pop songs are not accidents, and they are too plentiful to be the products of so-called “inspiration”. Pop songwriting is a craft that can be learned and applied with practice. I’d like to share what I’ve learned over the years from both my own writing and conversations with many professional songwriters. Hopefully you can apply these tips to your own songs! The elements of a great pop song are as follows: 1. Song Structure Great songs start with a great structure. While there are several popular structures used in pop music today, what they all have in common is that they provide a balance between repetition and presenting new information. A great song structure is designed to keep giving your listener something new, but also provide them with enough familiarity to keep them engaged. Let’s first define the typical sections, or parts of a pop song: Verse: Tells the story – answers “who, what where, when and why?”. Lyrics usually change from verse to verse, while the melody usually stays the same (though it is sometimes embellished upon slightly with each passing verse). Pre-chorus (or “the climb”): Functions to build energy and lead the listener into the chorus. Chorus: Sums up the message of the song – answers the question “so what?”. Contains the song’s “hook”. Lyrics and melody usually stay the same in each chorus. Bridge: Provides lyrical and melodic contrast – usually by offering a different point of view or perspective (something we haven’t heard before). -

Nielsen Music Year-End Report Canada 2016

NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company 1 Welcome to the annual Nielsen Music Year End Report for Canada, providing the definitive 2016 figures and charts for the music industry. And what a year it was! The year had barely begun when we were already saying goodbye to musical heroes gone far too soon. David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Glenn Frey, Leon Russell, Maurice White, Prince, George Michael ... the list goes on. And yet, despite the sadness of these losses, there is much for the industry to celebrate. Music consumption is at an all-time high. Overall consumption of album sales, song sales and audio on-demand streaming volume is up 5% over 2015, fueled by an incredible 203% increase in on-demand audio streams, enough to offset declines in sales and return a positive year for the business. 2016 also marked the highest vinyl sales total to date. It was an incredible year for Canadian artists, at home and abroad. Eight different Canadian artists had #1 albums in 2016, led by Drake whose album Views was the biggest album of the year in Canada as well as the U.S. The Tragically Hip had two albums reach the top of the chart as well, their latest release and their 2005 best of album, and their emotional farewell concert in August was something we’ll remember for a long time. Justin Bieber, Billy Talent, Céline Dion, Shawn Mendes, Leonard Cohen and The Weeknd also spent time at #1. Break out artist Alessia Cara as well as accomplished superstar Michael Buble also enjoyed successes this year. -

Special Edition Band Songlist

(revised for January 2021) POP/DANCE 24-Karat Magic Bruno Mars Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan All About The Bass Meghan Trainor Attention Charlie Puth Bad Romance Lady Gaga Bang Bang Ariana Grande/Nicki Minaj Bidi Bidi Bom Bom Selena Gomez Big Time Peter Gabriel Billie Jean Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey California Gurls Katy Perry Can't Stop the Feelin' Justin Timberlake Celebration Kool & The Gang Cheap Thrills Sia Cheerleader Felix Jaehn Chunky Bruno Mars Conga Gloria Estefan and The Miami Sound Machine Crazy In Love Beyoncé Dancing Queen Abba Donna Summer Medley Donna Summer Don't Cha Pussycat Dolls Don't Stop The Music Rhianna Drag Me Down One Direction Ex's and Oh's Elle King Faith George Michael Family Affair Mary J Blige Fancy Iggy Azalea feat. Charli XCX Feel It Still Portugal, The Man Finesse Bruno Mars/Cardi B Footloose Kenny Loggins Funkytown Lipps, Inc. Girls Just Wanna Have Fun Cyndi Lauper Give Me Everything Pitbull Good Kisser Usher Groove is in The Heart Deee-Lite Happy Pharrell Williams Havana Camilla Cabello Hella Good No Doubt I Feel For You Chaka Khan I Gotta Feelin' Black Eyed Peas I Wanna Dance With Somebody Whitney Houston I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor Intentions Justin Bieber I'm Like A Bird Nelly Furtado Jealous Nick Jonas Just Dance Lady Gaga Kiss Prince Lady Marmalade LaBelle/Shakira Last Dance Donna Summer Leave Your Hat On Joe Cocker Let's Go Crazy Prince Let's Groove Tonight Earth, Wind and Fire Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars Love on Top Beyoncé -

Grouplove/51765840/1?Loc=Interstitialskip

December 9, 2011 http://www.usatoday.com/life/music/ontheverge/story/2011-12-06/on-the-verge-with-indie-rock-group-grouplove/51765840/1?loc=interstitialskip Grouplove grew out of friendship By Korina Lopez, USA TODAY Group love, indeed: This Los Angeles-based quintet certainly lives up to its name. "We never planned to be a band. We were friends first and we just love being together," says lead singer Christian Zucconi. "Grouplove grew organically from that love." Their debut album, with the tongue-in-cheek title Never Trust a Happy Song, is quickly spreading the love, too. Their sweet and savory mix of jangly, upbeat melodies, Zucconi's anguished howl and keyboardist Hannah Hooper's coquettish backup vocals have been making the rounds in indie rock circles and on the charts. Joyful, noisy single Colours peaked at No. 12 on USA TODAY's alternative chart. Another track, Tongue Tied, lassoed the new iPod Touch commercial, which ran during the Grammy nominations concert and has continued since Thanksgiving. Add Grouplove's lock as the opening band for Young the Giant's tour in March and April, and it's no wonder they're so lovey-dovey. Happy accidents: Zucconi wasn't always this upbeat. "Before Grouplove, I was in other bands, but the timing never seemed right," he says. "I'd wake up every day depressed, I spent so many years miserable doing music. But it's wonderful now how we overcame everything together. It's funny that Grouplove is such a happy band." The band members met each other in 2008 at an artist commune in Crete. -

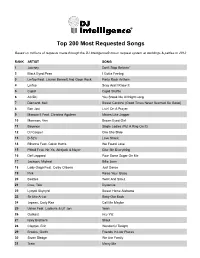

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

What Makes a Good Song? Exploring Popular Songs A

SECOND ARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSI C – WHAT MAKES A GOOD SONG? K NOWLEDGE ORGANISER What Makes a Good Song? Exploring Popular Songs A. Form and Structure in Pop Songs B. Typical Pop Song Structure C. Key Words FORM AND STRUCTURE – the different sections MELODY – The main tune of a popular song, often sung by the LEAD SINGER or sometimes of a piece of music or song and how they are INTRO played on instruments within the band e.g. LEAD GUITAR. A melody can move by STEP ordered. using notes that are next to or close to one another this is called CONJUNCT MOTION, or a INTRO – The introduction sets the mood of a VERSE 1 melody can move by LEAPS using notes that are further apart from one another which is song. It is often instrumental but can called DISJUNCT MOTION. The distance between the lowest pitched and highest pitched note in a melody is called the MELODIC RANGE. occasionally start with lyrics. VERSE 2 CHORD – A group of two or more pitched notes played at the same time. VERSES – Verses introduce the song theme. They CHORUS BASS LINE – The lowest pitched part of a song, often performed by bass instruments such are usually new lyrics for each verse which helps as the BASS GUITAR. The bass line provides the harmonies on which the chords are to develop the song’s narrative, but the melody is VERSE 3 constructed. the same in all verses. ACCOMPANIMENT – Music that accompanies either a lead singer or melody line – often PRE-CHORUS - A section of music that occurs CHORUS known as the “backing” – provided by a band or BACKING SINGERS. -

Music Industry Report 2020 Includes the Work of Talented Student Interns Who Went Through a Competitive Selection Process to Become a Part of the Research Team

2O2O THE RESEARCH TEAM This study is a product of the collaboration and vision of multiple people. Led by researchers from the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and Exploration Group: Joanna McCall Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Barrett Smith Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Jacob Wunderlich Director, Business Development and Applied Research, Exploration Group The Music Industry Report 2020 includes the work of talented student interns who went through a competitive selection process to become a part of the research team: Alexander Baynum Shruthi Kumar Belmont University DePaul University Kate Cosentino Isabel Smith Belmont University Elon University Patrick Croke University of Virginia In addition, Aaron Davis of Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach of the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce contributed invaluable input and analysis. Cluster Analysis and Economic Impact Analysis were conducted by Alexander Baynum and Rupa DeLoach. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 - 6 Letter of Intent Aaron Davis, Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach, The Research Center 7 - 23 Executive Summary 25 - 27 Introduction 29 - 34 How the Music Industry Works Creator’s Side Listener’s Side 36 - 78 Facets of the Music Industry Today Traditional Small Business Models, Startups, Venture Capitalism Software, Technology and New Media Collective Management Organizations Songwriters, Recording Artists, Music Publishers and Record Labels Brick and Mortar Retail Storefronts Digital Streaming Platforms Non-interactive -

Song Writers & Pr Oducers

DELETE ME DATA FOR WEEK OF 01.02.2021 HOT 100 SONGWRITERSTM HOT 100 PRODUCERSTM #1 #1 1 8 WKS JOHNNY MARKS 1 4 WKS OWEN BRADLEY 2 MEREDITH WILLSON 2 LEE GILLETTE 3 IRVING BERLIN 3 ROBERT MERSEY 4 JOSE FELICIANO 4 PHIL SPECTOR 5 GEORGE MICHAEL 5 MILT GABLER TIE 6 MARIAH CAREY 6 BING CROSBY TIE 6 WALTER AFANASIEFF 7 RICK JARRARD 8 TAYLOR SWIFT 8 AARON DESSNER TIE 9 JIM BOOTHE 9 GREG WELLS TIE 9 JOE BEAL 10 GEORGE MICHAEL 11 PAUL MCCARTNEY TIE 11 MARIAH CAREY TIE 12 EDWARD POLA TIE 11 WALTER AFANASIEFF TIE 12 GEORGE WYLE 13 GREG KURSTIN 14 KELLY CLARKSON 14 ART SATHERLEY 15 R. ALEX ANDERSON 15 ILYA TIE 16 JULE STYNE 16 FINNEAS TIE 16 SAMMY CAHN 17 JOHN SCOTT TROTTER 18 MARVIN BRODIE 18 D.A. GOT THAT DOPE TIE 19 MEL TORME 19 DAVID FOSTER TIE 19 ROBERT WELLS 20 PAUL MCCARTNEY 21 GREG KURSTIN TIE 21 MR. FRANKS TIE 22 LEROY ANDERSON TIE 21 TBHITS TIE 22 MITCHELL PARISH 23 STEVE SHOLES 24 ARIANA GRANDE 24 LIL JU 25 FINNEAS 25 RYAN METZGER COUNTRY SONGWRITERSTM COUNTRY PRODUCERSTM #1 #1 1 4 WKS MORGAN WALLEN 1 34 WKS JOEY MOI 2 RANDY MONTANA 2 GREG WELLS 3 JOSH OSBORNE 3 DAN SMYERS 4 ERNEST KEITH SMITH 4 ROSS COPPERMAN 5 JON NITE 5 SCOTT MOFFATT TIE 6 GABBY BARRETT 6 ZACH KALE TIE 6 ZACH KALE 7 JON RANDALL 8 LUKE COMBS 8 SCOTT HENDRICKS 9 TAYLOR SWIFT 9 DANN HUFF 10 HILLARY LINDSEY 10 JAY JOYCE R&B/HIP-HOP SONGWRITERSTM R&B/HIP-HOP PRODUCERSTM #1 #1 1 9 WKS LIL BABY 1 1 WK D.A. -

Why Hip-Hop Is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music

Why Hip-Hop is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez Advisor: Dr. Irene Mata Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies May 2013 © Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 “These Are the Breaks:” Flow, Layering, Rupture, and the History of Hip-Hop 6 Hip-Hop Identity Interventions and My Project 12 “When Hip-Hop Lost Its Way, He Added a Fifth Element – Knowledge” 18 Chapter 1. “Baby I Ride with My Mic in My Bra:” Nicki Minaj, Azealia Banks and the Black Female Body as Resistance 23 “Super Bass:” Black Sexual Politics and Romantic Relationships in the Works of Nicki Minaj and Azealia Banks 28 “Hey, I’m the Liquorice Bitch:” Challenging Dominant Representations of the Black Female Body 39 Fierce: Affirmation and Appropriation of Queer Black and Latin@ Cultures 43 Chapter 2. “Vamo a Vence:” Las Krudas, Feminist Activism, and Hip-Hop Identities across Borders 50 El Hip-Hop Cubano 53 Las Krudas and Queer Cuban Feminist Activism 57 Chapter 3. Coming Out and Keepin’ It Real: Frank Ocean, Big Freedia, and Hip- Hop Performances 69 Big Freedia, Queen Diva: Twerking, Positionality, and Challenging the Gaze 79 Conclusion 88 Bibliography 95 3 Introduction In 1987 Onika Tanya Maraj immigrated to Queens, New York City from her native Trinidad and Tobago with her family. Maraj attended a performing arts high school in New York City and pursued an acting career. In addition to acting, Maraj had an interest in singing and rapping.